The Roman toga was a marvelous garment that was designed to keep you in style and warm in all seasons, even if you decided to wear it with nothing underneath as it was worn first by the Lydians and then by the Etruscans and by early Romans, before they lost touch with the elements in middle-Republican times.

The original shape and size of the toga are in dispute, but by the late Republic and into the Empire period, when it became the identifying mark of Roman citizenship, it was a very large single piece of cloth. The longer dimension of the ideal ceremonial toga was three times the wearer's height plus his waist measurement. (The wearer was almost always male.) Its width would be seven or eight feet, also depending on the wearer's height and girth. The corners were severely rounded until the shape was a true oval -- literally egg-shaped, with the one end rounded less than the other.

For most purposes, the toga would be of wool in its natural color, but political candidates might bleach their togas or whiten them with chalk so they would be more easily seen and recognized in crowds. In fact, the word "candidate" comes from this ancient whiter-than-white toga custom -- the brightened toga was the toga candida (candida = bright) and those who wore them, while seldom the best, were most often the candidati, the brightest. The toga candida might get you elected to office by your fellow senators, but it also was a source of derision in drama and on the streets. The same was true of its opposite, the toga sordita, a dirty and worn toga, accompanied by disarranged hair and general messiness. It was affected either when seeking a big favor from a patron or when appearing as the accused in a civil law court -- the idea of the toga sordita seemed to be some variation of "I am too poor and distraught to take care of myself, so please have pity."

Color and decoration gradually crept in. Even in Etruscan times, a narrow maroon stripe (they were never really purple) was added to one long side of the cloth. Boys later wore this narrow-striped version before they were acknowledged to be old enough to wear the plain "manly" toga, the toga virilis, usually in March during the feast of the Liberalia after their 16th birthday. Certain magistrates and priests also wore the same narrow-striped toga as the boys, but they were visibly old enough not to be mistaken for boys.

Senators and higher got to wear a toga with a broad maroon stripe. Later emperors went to all-maroon togas, at times with gold embroidery, in a style previously reserved for generals celebrating victories. Nero is said to have worn semi-transparent yellow silk, but we know what kind of pervert he was. Cloth of different materials and even patterned cloths were eventually worn, but purists (those who wore the original plain toga, the toga pura) were offended.

In Lydian and Etruscan times and in the earliest times of the pre-republican monarchy, women also wore togas, but theirs were more strategically draped in front to prevent male gawking. Togas for women rapidly went out of style, and some scholars say it happened when Roman men started dating Latin and raping Sabine women: the image of Roman female modesty thereafter became the Latin one, which didn't include loosely draped togas. In fact, the loosely draped toga on a woman soon became and long remained the sign of a loose woman -- only prostitutes wore them. There are stories of Agrippina the Younger, Nero's mother, appearing in public in a toga, presumably to emphasize her power and man-like authority. Some of the same stories say her ploy backfired when the mob whispered "harlot" after she passed. Foreigners and slaves were also forbidden the toga, and after a while a new word, "togatus", a toga-wearer came to mean "male Roman citizen.

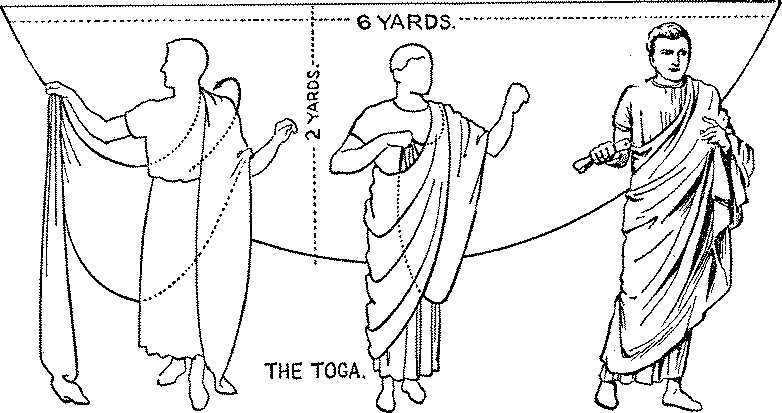

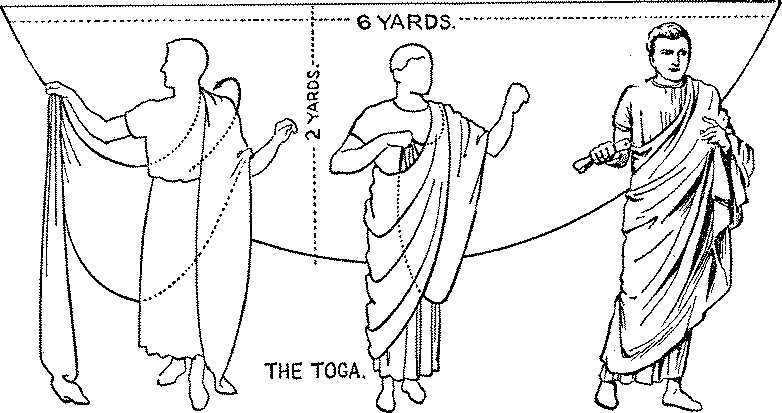

So how do one get this huge

garment

onto oneself? First, no self-respecting Roman ever put one on without

the

help of servants -- it's beastly difficult to do so without dragging it

around the dusty floor. But here's how it's done. Two people, neither

of

which is the wearer, stretch the toga out lengthwise and fold it

lengthwise

in thirds. The edge with the stripe, if it has one, is folded over and

the other edge is folded under. The narrower, more rounded end is

draped

forward over the left shoulder -- striped side forward and the striped

edge near the neck -- with the tip just above the wearer's toes. The

long

remainder is loosely wrapped around the wearer's back and brought under

his right arm. That accounts for two thirds of the length. The

remaining

third is thrown back over the left shoulder. It's on, and the weight of

the wool keeps it on as long as the wearer maintains his poise and dignitas

--

jumping around was not consistent with a modest appearance. The left

arm

was usually held bent and close to the body. Sometimes, especially if a

spirited speech in the Senate was on the wearer's schedule, a slave

might

reach under the left armpit and stitch or pin together (as invisibly as

possible) the two long dangling ends. There were no pockets, but your

slaves

carried most of your stuff anyway. And you could always tuck a copy of

your speech, love poems, secret dispatches, or anything else too

valuable

to entrust to a slave, into the sinus, the folded part at your

right

hip and rising in front of your body. And that's your basic toga.

In really cold weather, it was OK to tuck the right arm under the middle segment that normally went around the right hip and even to unfold and bring that side up around the neck. This maneuver might expose other parts that the wearer wanted to keep warm so winter togas were often wider as well as heavier than warm weather gear, and they might be folded in half rather than in thirds to get extra coverage of the lower body. Most often, however the toga was worn over a knee-length tunic that provided extra warmth and some modesty. There were also tropical or summer togas, looser woven and finer wool, and perhaps cut in half down the long dimension to make fewer folded layers over the skin.

Toward the very end of the empire, togas shrunk drastically to less than half of the previous length and were fastened at the left shoulder, much in the manner of collegiate toga-party bed sheets. But these mini-togas were purely ceremonial and were worn over more prosaic clothes. Some authorities surmise that the mini toga may have evolved into the capes worn in later days, either on the left shoulder or draping from the left shoulder to the right hip. Whatever the case, everyone knew that mini-togas or capes weren't real togas.

Don't read the Internet toga-trash! Go to these sites for good info:

The Smith Dictionary excerpted at the Lacus Curtius site -- the source of most good toga information http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Toga.html

Another Smith Dictionary excerpt on legal rights of boys, youths, and men. Putting on the manly toga is halfway down the page: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Impubes.html

Julilla at Villa Ivlilla (ancientsites.com) shows a late empire, semi-oval, summer toga with pictures of how to put it on: http://www.villaivlilla.com/toga.htm

What the women wore -- Late empire Roman women's makeup and fashion, also from Julilla: http://www.villaivlilla.com/v-women.htm