Florence and Rome

Click on small images or links to see larger images.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201-ItalyMap.jpg

Map: Division of the Italian Peninsula during the Renaissance

What was wrong with Rome? Or put another way, why didn't the Renaissance start there instead of in Florence?

http://mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201a-Gibbon.jpg

http://mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201b-PoggioBracciolini.jpeg

http://mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201c-RomeRuins1700s.jpg

http://mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201d-Colosseum.jpg

http://mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201d-ColosseumCollapse.jpg

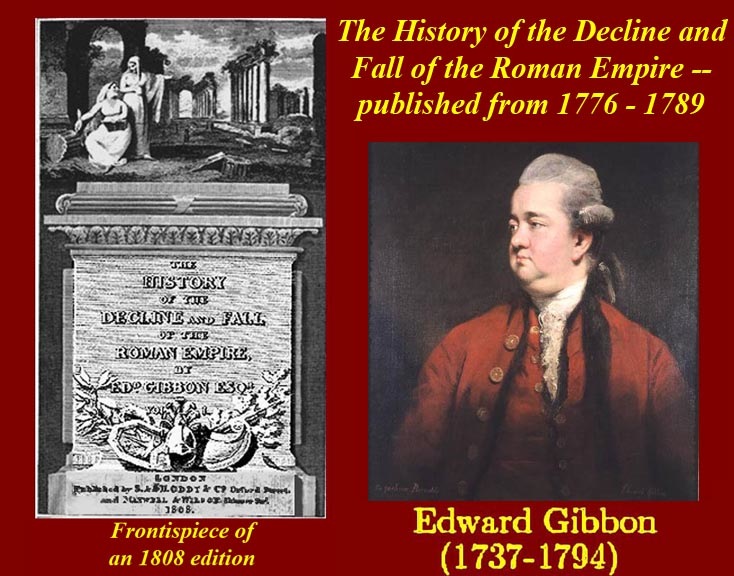

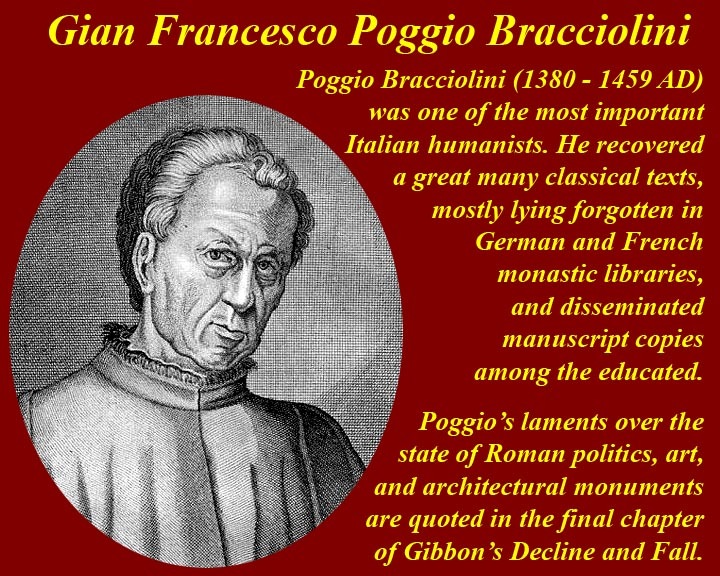

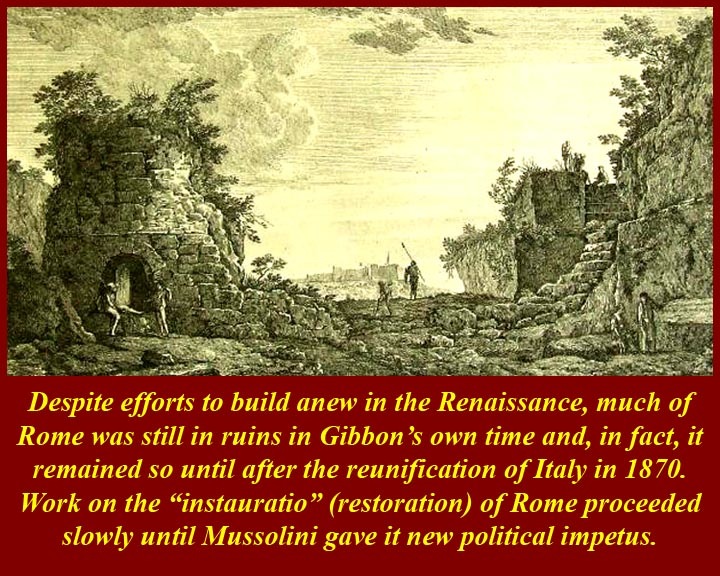

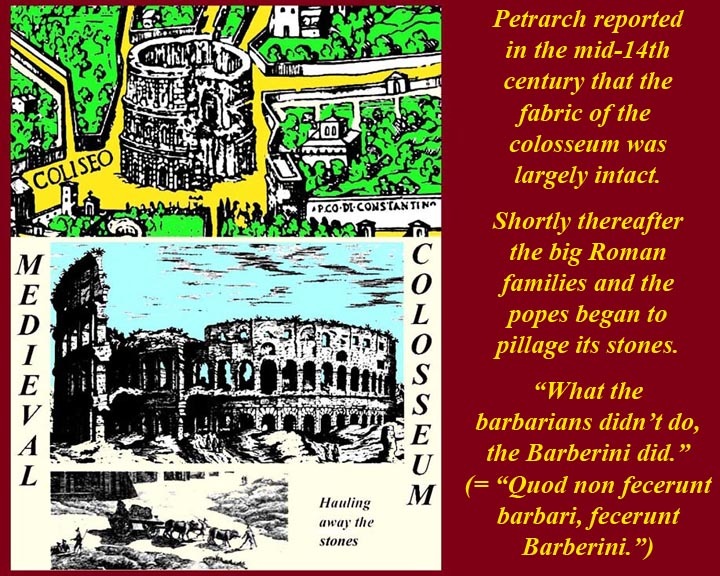

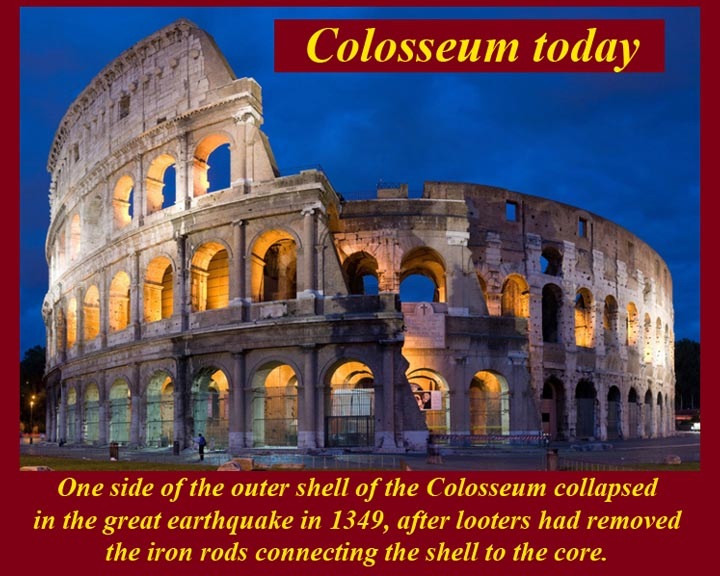

Gibbon, in the last (LXXI) chapter of his "Decline and Fall" (1776 - 1789), quoted Poggio Bacciolini extensively on the ruination of Rome. Poggio, who lived at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th centuries, had written many letters, some of which were available to Gibbon. Poggio complained (loosely translated) that the Capitoline temple was overthrown, its gold pillaged, its sacred ground disfigured by thorns and brambles. The triumphal route was obliterated by vines and the Senators' benches concealed by a dunghill (i.e., the cloaca maxima had collapsed after the Byzantines had stolen the metal staples that held it together). The Palatine hill was strewn with shapeless and enormous fragments. The other hills were vacant space interrupted by ruins and gardens. The Forum was fenced for cultivation of pot herbs and open for the reception of swine and bufalo. Public and private edifices, which had been built for eternity, lie prostrate , naked, and broken like the limbs of a mighty giant, and the ruin is more visible from the stupendous relics that have survived the injuries of time and fortune.

Gibbon gave four reasons for the ruinous state of the city:

1) injuries of time and nature -- no work force to effect repairs after weathering and earth tremors.

2) hostile attacks of Barbarians and Christians.

3) use and abuse of building materials.

4) domestic quarrels of Romans.

Gibbon said that with the restoration of a unified Papacy resident in Rome (after 1420) the clouds of barbarism were gradually dispelled -- the peaceful authority of Pope Martin V restored the ornaments of the city and the "order of the ecclesiastical state."

But what didn't work was the "natural root" (i.e., productive hinterland) of a great city. The greater part of the Campagna was reduced to a dreary and desolate wilderness; overgrown princely and clerical estates cultivated by the lazy hands of indigent and hopeless vassals; scanty harvests benefiting monopolies.

Monarchical court revenues -- even New World moneys -- were squandered by Popes and "nephews". But the "squandering" was in rebuilding churches, palaces, etc. (especially the new St. Peters Church); replacement of ancient ornamentation with new or "re-placed" art; restoring aqueducts or building new ones (as Pope Sixtus V had done).

Who Ruled Rome during the chaotic "dark ages"?

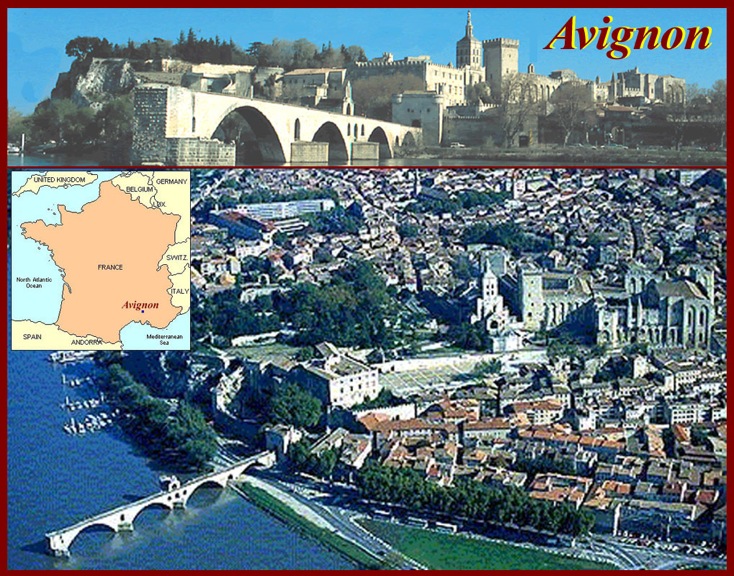

Power had shifted from the imperial bureaucracy to the Barbarian monarchs and finally to the Popes (through claims derived from the fraudulent "Donation of Constantine"). But, in the final stages, the Popes lost major chunks of Italy and even eventually lost temporal power in Rome itself. "Families" took over and fought each other. The Popes had to seek "protection" from the French, after which they were taken to "safety" in Avignon (1309-1377).

While the Popes were in Avignon rapid changeovers took place:

The Colonna family (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonna_family) fought incessantly with the Orsini (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orsini_family), and in one of their skirmishes a young man, the brother of Cola di Rienzi was killed. This led Rienzi to organize the people (1347) -- the equivalent of the ancient Roman mob -- against all of the "noble" families. He was temporarily successful, until the "families" brought in their rural supporters. Rienzi fled and eventually ended up in Germany where a local prince arrested him and packed him off to Avignon where he was held. A change in Avignonese attitude (and popes) led to the release of Rienzi -- under the influence of Petrarch -- and he was sent back to Rome (1354). The idea was that he would again undermine the "families" and raise the influence of the Popes. Rienzi, however, by his own excesses (including bathing in the baptismal basin at St. John Lateran), lost the support of the populace (the Roman mob). He was again threatened by the "families", and when he range the bell at the "Palazzo Senatorio" to assemble his popular supporters, they failed to show up. He was quickly dispatched with a sword thrust. The families were again in power, but they weakened themselves by infighting. (For more on this whole sordid mess, see http://www.ccel.org/g/gibbon/decline/volume2/chap70.htm, which is Chapter LXX if Gibbon's Decline and Fall.)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201e-PetrarchAvignon.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201f-Avignon.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201g-SchismMap.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0201h-TwoPopes.jpg

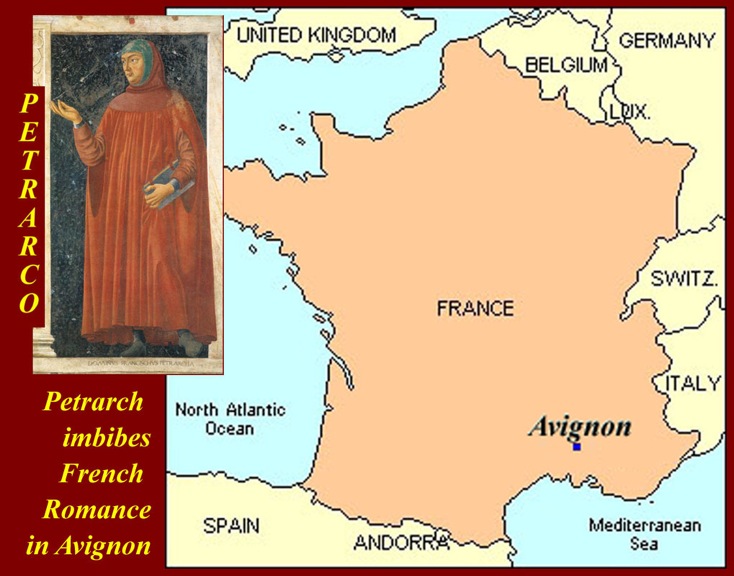

Francesco Petrarca (July 20, 1304 – July 19, 1374), known in English as Petrarch, was an Italian scholar, poet and one of the earliest Renaissance humanists. Petrarch is sometimes called the "Father of Humanism". His sonnets were admired and imitated throughout Europe during the Renaissance and became a model for lyrical poetry. Petrarch was also known for being one of the first people to refer to the Dark Ages. He was one of the first since ancient times to collect books, manuscripts, and coins, and has been called “the first tourist" for his love of travel.

Petrarch's writings reflect a more worldly spirit than that of the Middle Ages. Marked by technical perfection and formal polish, his poems about his beloved Laura are classics of the Italian language. Laura was married woman who has never been positively identified, but who may have been the wife of Count Hugues de Sade. Petrarch's Italian language lyrics to Laura, in the troubadour tradition of courtly (i.e., unrequited) love, which he imbibed in Avignon, were collected as the Canzoniere (Songbook). They advanced the growth of Italian as a literary language and popularized the form of the sonnet that is called the Petrarchan sonnet. Many years after Laura's death in 1348, Petrarch wrote Trionfi, a religious allegory in which she was idealized. Most of Petrarch's other writings were in Latin.

Petrarch wrote mainly in Latin, which he hoped to restore to classical purity. Cicero, Virgil, and Seneca were his literary models. Among his works were books of history, biography, and moral philosophy; a dialogue with Saint Augustine; and volumes of letters. After being crowned in Rome as poet laureate (1341) for his Latin epic, Africa, he was honored throughout Italy. Giovanni Boccaccio turned to scholarship under Petrarch's influence. Although Petrarch wrote poems in praise of a free Italy, he accepted the patronage of the Visconti, tyrants of Milan, from 1353 to 1362 and also spent some time in the Avignon papal court. He supported the aspirations of Cola di Rienzi, but he also may have been Rienzi's mentor/controller for the Avignon Popes.

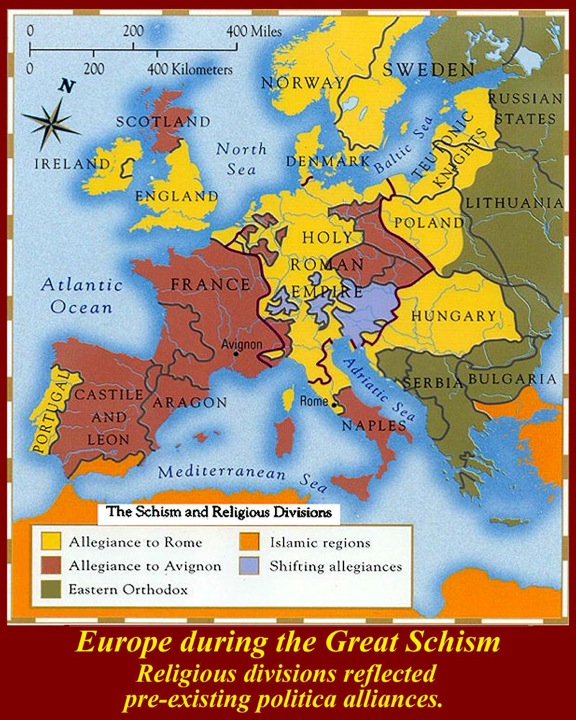

The Great Western Christianity or Papal Schism (also known as the Western Schism) was a split within the Roman Catholic Church from 1378 to 1417, and it followed immediately after the Avignon "captivity", during which the Popes decamped from Rome and took up French protection. After the "official" (i.e., Roman version ) end of the Avignon period there were two simultaneous claimants to the Papacy. Driven by politics rather than any real theological disagreement, the schism was ended by the Council of Constance (1414–1418). The simultaneous claims to the papal chair of two different men -- and for a short time three -- hurt the reputation of the office.

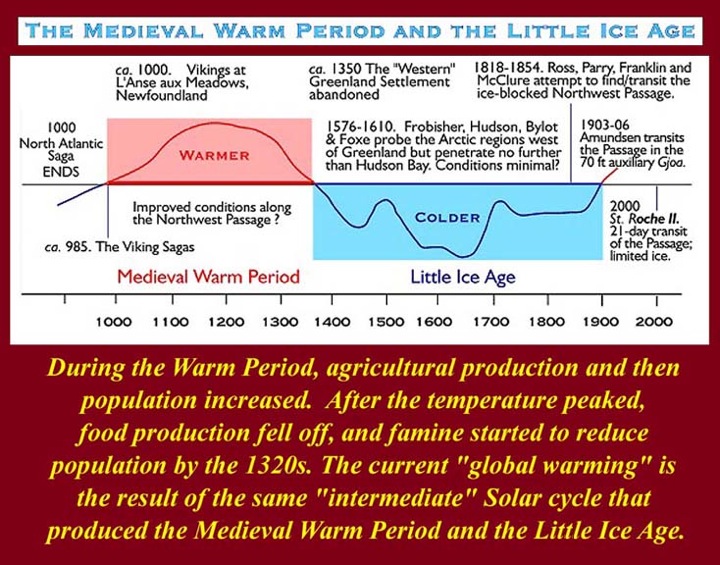

Meanwhile, the first wave of the "Black Plague" swept through Italy (1347-49) wiping out at least thirty percent of the population. The strength of this particular iteration of bubonic/pneumonic/enteric plague resulted, in large part, from the fact that all of Europe was already suffering from famine caused by the end of the Medieval warm period. See also this graphic from the Medieval Rome course:

The Popes, of course, eventually came back to Rome, but not without problems. A new "Roman" pope was elected, leading to "The Great Western Schism", about which more will be said later. For now, it needs only to be said that many authors start their accounts of the Renaissance in Rome with the end of the Great Western Schism (ca. 1417) and/or the beginning of "The Second Era of the Papal States" (ca. 1431).

Why was Florence ready for an artistic Renaissance?

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202-Florence.jpg

Florence today from across the Arno. The simple answer to Florentine readiness was money and especially money concentrated in one family, the Medici. Unlike in Rome, where the many "families" wasted their resources fighting against each other, there really was only one dominant family in Florence. Other families in Florence had political power aspirations, but they were never strong enough to permanently oust the Medici -- even when they were aided by outsiders like the Popes and the French..

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202a-MediciArms.jpg

Medici Arms -- the six little red balls are said to represent pills which some unknown "medicus" (a doctor) would have prescribed. Medici origins are obscure, so it's not known whether there was a real eponymous Medici doctor who made the seed money for the family. What is known is that the Medici were successful late medieval wool traders and that the Medici family was connected to most other elite families of the time through strategic marriages, partnerships, or employment, as a result of which the Medici family had a position of centrality in the social network: several families had systematic access to the rest of the elite families only through the Medici, perhaps similar to banking relationships. This has been suggested as a reason for the rise of the Medici family. For a short summary of the Medici family, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Medici.

Some Illustrius Medici:

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202ab-GiovanniDiBicciMedici.jpg

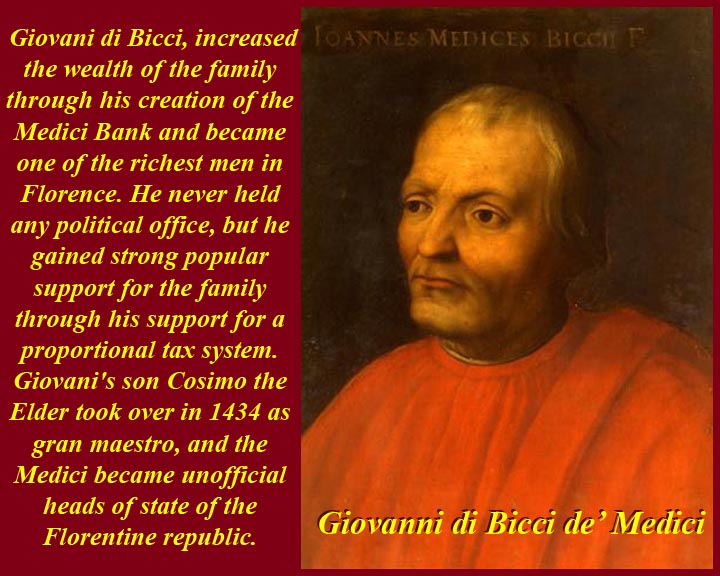

Giovani di Bicci, increased the wealth of the family through his creation of the Medici Bank, and became one of the richest men in the city of Florence. Although he never held any political charge, he gained strong popular support for the family through his support for the introduction of a proportional taxing system. Giovani's son Cosimo the Elder took over in 1434 as gran maestro, and the Medici became unofficial heads of state of the Florentine republic.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202b-CosimoVecchio.jpg

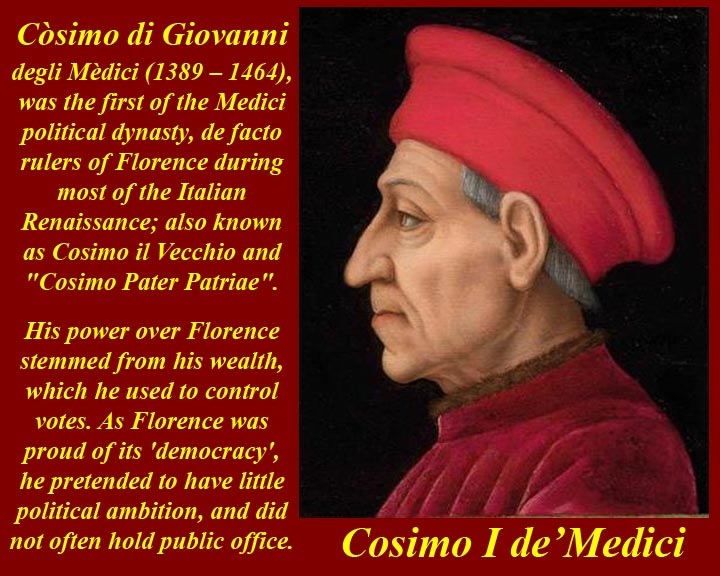

C̣simo di Giovanni degli Mèdici (September 27, 1389 – August 1, 1464), was the first of the Medici political dynasty, de facto rulers of Florence during most of the Italian Renaissance. He is most often known as Cosimo "the Elder" ("il Vecchio") or "Cosimo Pater Patriae". This can get a little confusing: Cosimo "the Elder" is not Cosimo I. That title was taken later by the first Medici to become the Grand Duke of Tuscany. At any rate, Cosimo the Elder was exiled in 1433 by a cabal of other Florentine families, who thought he was becoming too powerful. He went to Venice and took his bank with him. Other bankers followed him and the Florentine money market crashed. Within a year he was invited back, and his power was restored.

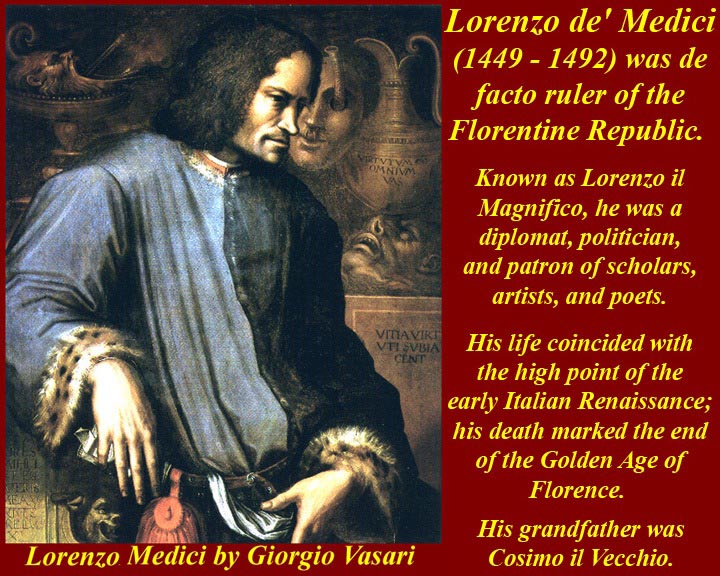

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202c-LorenzoByVasari.jpg

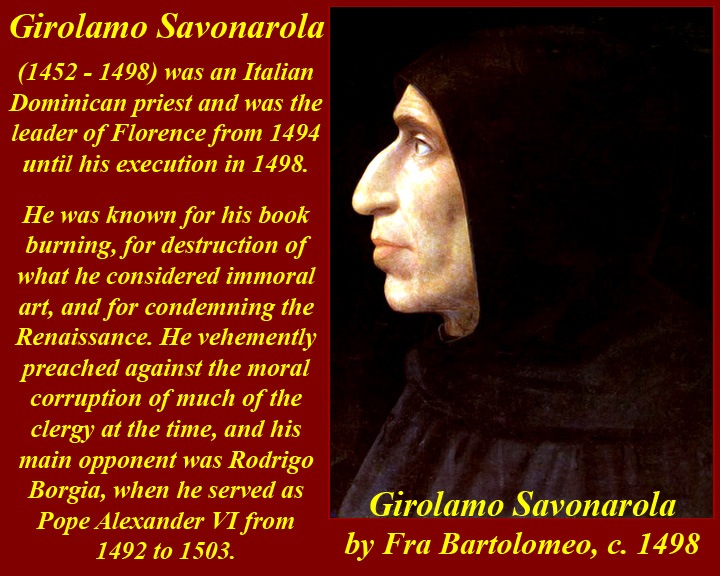

Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492), was more capable of leading and ruling a city; however, he neglected the family banking business, leading to its ultimate ruin. Although not a good banker, Lorenzo was the first of the great Medici patrons of art and architecture -- in fact, that's what broke the bank. To ensure the continuance of his family's success, Lorenzo planned his children's future careers for them. He groomed the headstrong Piero II to follow as his successor in civil leadership; Giovanni (future Pope Leo X) was placed in the church at an early age; and his daughter Maddalena was provided with a sumptuous dowry when she made the politically advantageous marriage to a son of Pope Innocent VIII. When Giuliano, Lorenzo's brother, was assassinated in church on Easter Sunday (the Pazzi plot of 1478, which also aimed to kill Lorenzo), Lorenzo adopted Giuliano's illegitimate son, Giulio de' Medici (1478-1535), the future Pope Clement VII. Unfortunately, all Lorenzo's careful planning fell apart to some degree under the incompetent Piero II, who took over as the head of Florence after Lorenzo's death. Piero was responsible for the expulsion of the Medici from 1494-1512 when the French invaded from the North. For a short period of time, Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican priest, ran Florence. (see below)

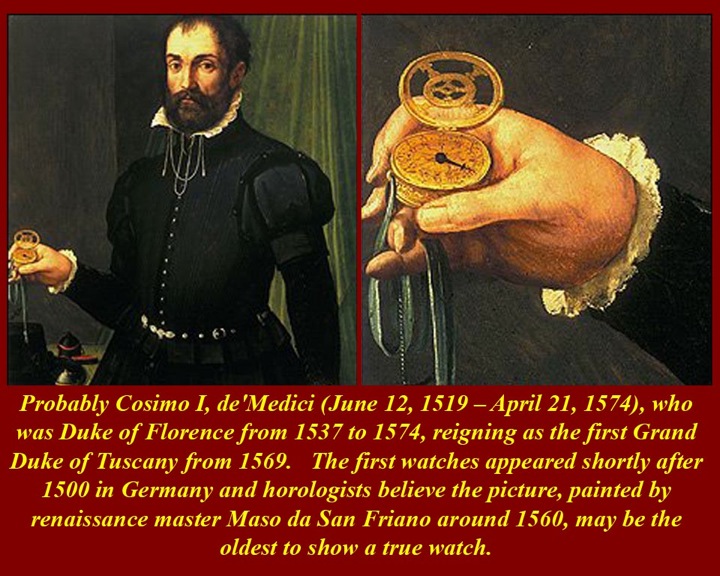

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202d-Cosimo-OldestWatchPainting.jpg

Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany, is famous for having a pocket watch. Horologists say that this painting by Maso da San Friano from the mid 1500s is the first appearance of a watch in art.

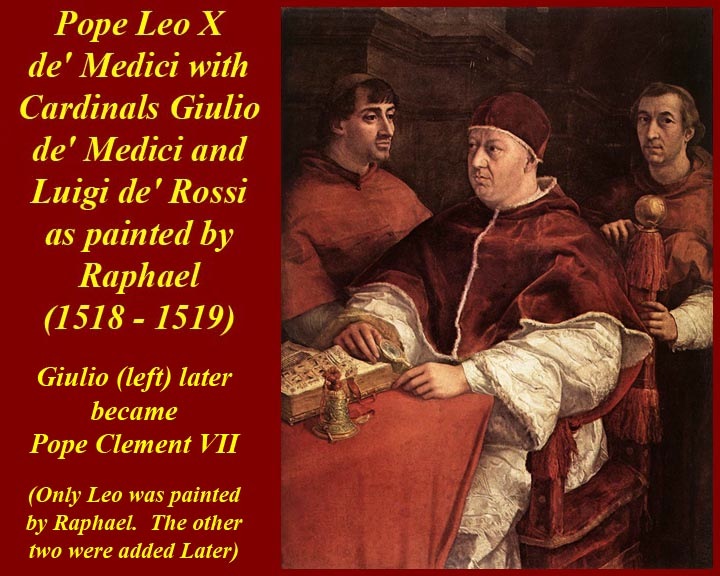

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202e-LeoXRaphael.jpg

Raphael painted the first Medici pope, Leo X (Giovanni, Lorenzo's son, who was Pope from 1513 - 1521), and some unknown artist later added the two Cardinals to his left and right. The one of the left is Giulio de' Medici, the illegitimate son of Lorenzo's brother Giuliano and adopted son of Lorenzo. Giulio became Pope Clement VII after Leo X died. (There was a scant year between Leo and Clement, during which Adrian VI was pope.) Lorenzo, it turned out, had not really been a financial naif -- he directed the Medici fortunes toward the even greater wealth of the Papal states.

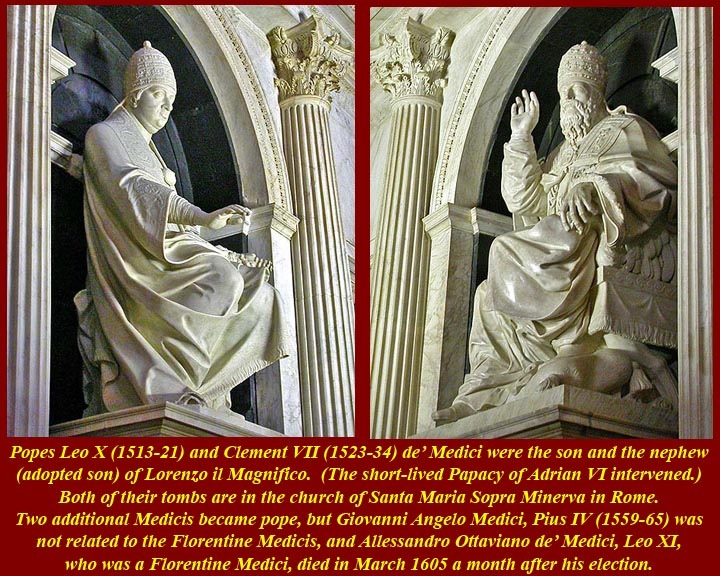

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202f-LeoX-ClementVII.jpg

Altogether there were four Medici popes. Leo X and Clement VII both had illustrious reigns and transferred the Medici artistic patronage to Rome, which ever after became the apex of Italian Renaissance art and architecture. After their reigns, popes could summon and commission artists and architects from all over Italy and beyond. Papal money and power (even threats of military action, abduction, and personal or mass excommunication) made sure that those who were summoned actually came to Rome. In most cases those drafted into the papal realms were only too glad to come. (A notable exception was Michelangelo, who would rather have stayed in Florence after Pope Julius II took him off the project to build Julius a tomb and told him to paint the Sistine chapel. The illustration shows the tombs of Leo and Clement, both of which are in the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva near the Pantheon in Rome, a church that they and subsequent popes heavily patronized.

A one hour video on Leo X and Clement VII is available on the internet at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmNbecu1V6I.

The other two Medici Popes were later: Giovanni Angelo Medici, Pius IV (1559 - 65), was not even related to the Florentine Medici. Allessandro Ottaviano de' Medici, Leo XI was a Florentine Medici, but he died within a month of his election in February of 1605, after catching a chill while moving into the papal residence (then in the Lateran Palace).

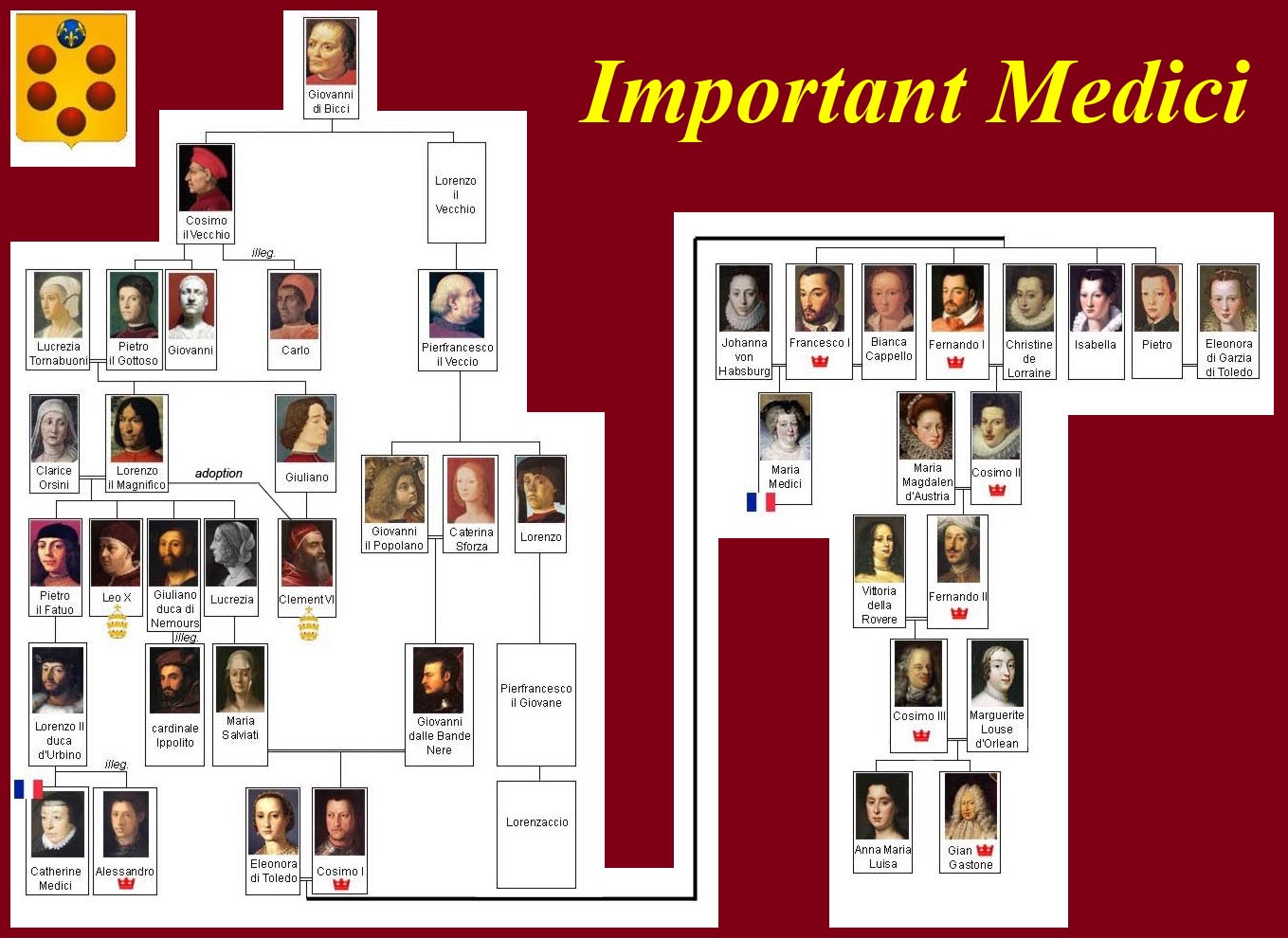

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202g-MediciTree.jpg

This is a much simplified family tree showing the descent of the main actors in the Florentine branch of the Family.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202h-Savonarola1.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202i-Savonarola2.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202j-Savonarola3.jpg

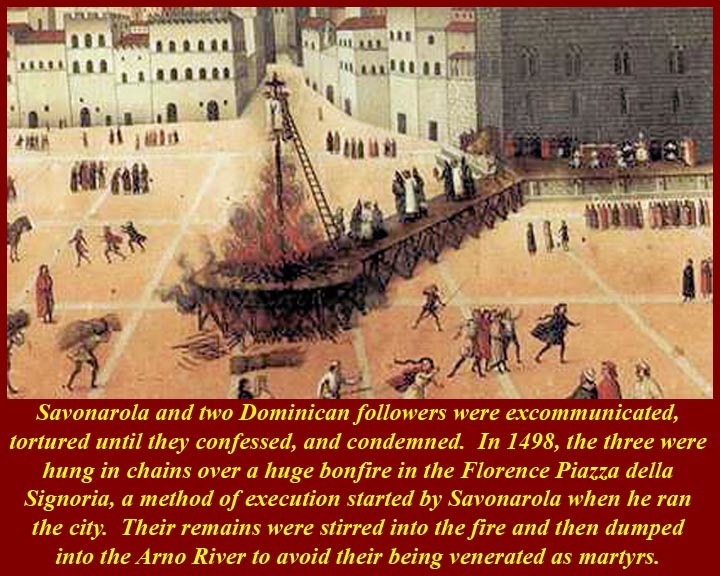

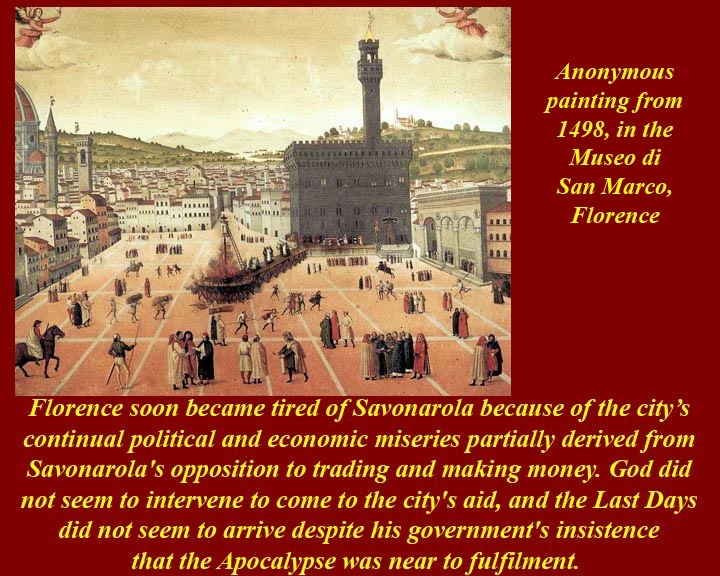

Girolamo Savonarola was a Dominican priest who preached against the "vanities" of the Renaissance. He was famous for (although he probably did not invent) the "bonfire of the vanities". Born in 1452, he was the leader of Florence from 1494 until his execution in 1498. He was known for his book burning, destruction of what he considered immoral art, and hostility to the Renaissance. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Rodrigo Borgia, when he was Pope Alexander VI, from 1492 to 1503. Because book-burning became associated with the Nazis in the 20th century, Savonarola sometimes has been characterized as a right-wing religious extremist. In fact, he was not that but rather he was a left-wing religious extremist. The penalty for crossing Savonarola, when he was in charge, was a particularly gruesome death suspended in chains from a cross over a raging bonfire. Savonarola and his two best henchmen eventually were killed the same way after they lost popular support (and after French support evaporated.) He was excommunicated by the Pope, tortured until he confessed, condemned, and turned over to the civil authorities for execution. A contemporary artist recorded the event -- the Bonfire of Savonarola.

For accounts of Savonarola's rise and fall, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girolamo_Savonarola and http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13490a.htm. The second internet link will take you to the Catholic Encyclopedia. The Catholic Church maintains that Savonarola was not, repeat not, a heretic; he was condemned for insubordination, not heresy.

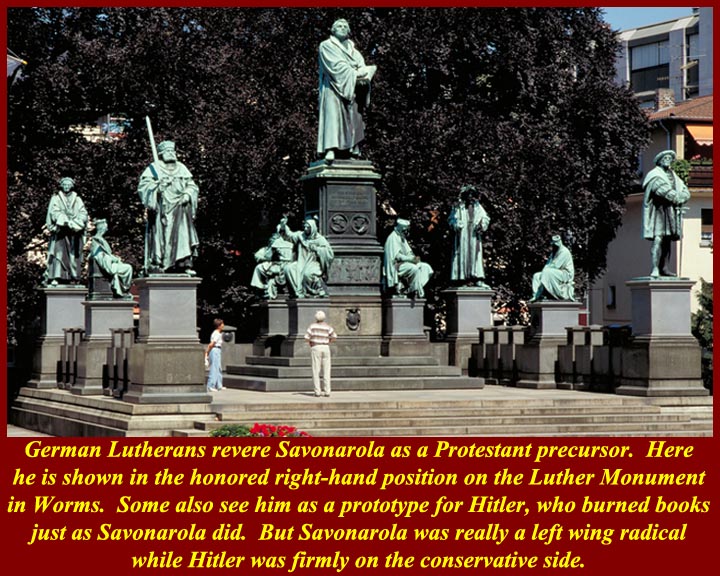

Many protestants consider Savonarola a predecessor of Martin Luther, and in Worms, Germany, where Luther refused to recant, the Luther statue has Savonarola in a supporting role -- he's the one in Dominican robes with his right hand raised: (http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0202k-Savonarola-Luther.jpg)

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0204-VasariLives.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205-SalaRegiaVasari.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205a-VasariSalaGrande.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205b-FlorenceDuomoDomeFresco.jpg

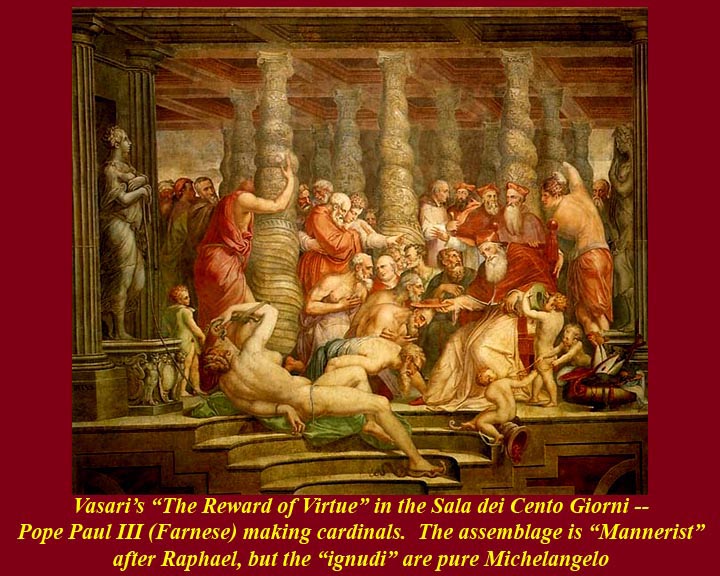

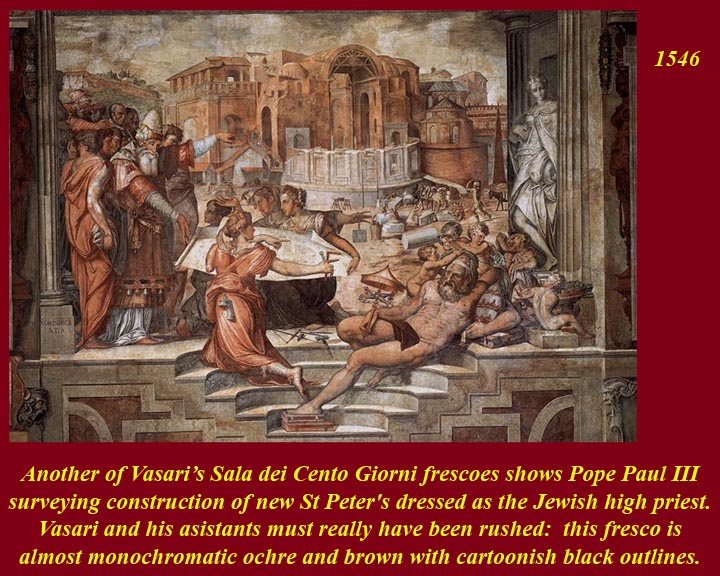

Giorgio Vasari (30 July 1511 – 27 June 1574) was an Italian painter and architect, who is today most famous for his biographies of Italian artists (a), considered the ideological foundation of art-historical writing. Vasari's "Lives" has a consistent and notorious bias in favor of Florentines and tends to attribute to them all the developments in Renaissance art -- for example, the invention of engraving. Venetian art in particular (along with arts from other parts of Europe), is systematically ignored in the first edition. Between the first and second editions, Vasari visited Venice and while the second edition gave more attention to Venetian art (finally including Titian) it did so without achieving a neutral point of view. Vasari's biographies are interspersed with amusing gossip. Many of his anecdotes have the ring of truth, while others are inventions or generic fictions, such as the tale of young Giotto painting a fly on the surface of a painting by Cimabue that the older master repeatedly tried to brush away, a genre tale that echoes anecdotes told of the Greek painter Apelles. With a few exceptions, however, Vasari's aesthetic judgment was acute and unbiased. He did not research archives for exact dates, as modern art historians do, and naturally his biographies are most dependable for the painters of his own generation and those of the immediate past. Modern criticism, with new materials opened up by research, has corrected many of his traditional dates and attributions. The work remains a classic, though it must be supplemented by modern critical research. The myth of Florentine domination of the Italian Renaissance is at least partly based on Vasari's biases.

Vasari's own Mannerist paintings were more admired in his lifetime than afterward. He was consistently employed by patrons in the Medici family in Florence and Rome, and he worked in Naples, Arezzo and other places. Many of his pictures still exist, the most important being the Sala Regia in the Vatican (b), wall and ceiling paintings in the great Sala di Cosimo I (Sala Grande) of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence (c), where he and his assistants were at work from 1555, and his uncompleted frescoes inside the vast cupola of the Florence Duomo(d), which were finished by Federico Zuccari and with the help of Giovanni Balducci.

Links to Vasari's works in museums around the world are at http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/vasari_giorgio.html.

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)(e)

(f)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205c-VasariUffizi.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205d-VasariCorridor.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205e-VasariCorridorPonteVecchio.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205f-VasariCorridorGallery.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0205g-TorreMannelli.jpghttp://www.mmdtkw.org

http://www.mmdtkw.org//RenRom0205h-VasariCorridorPittiEnd.jpg

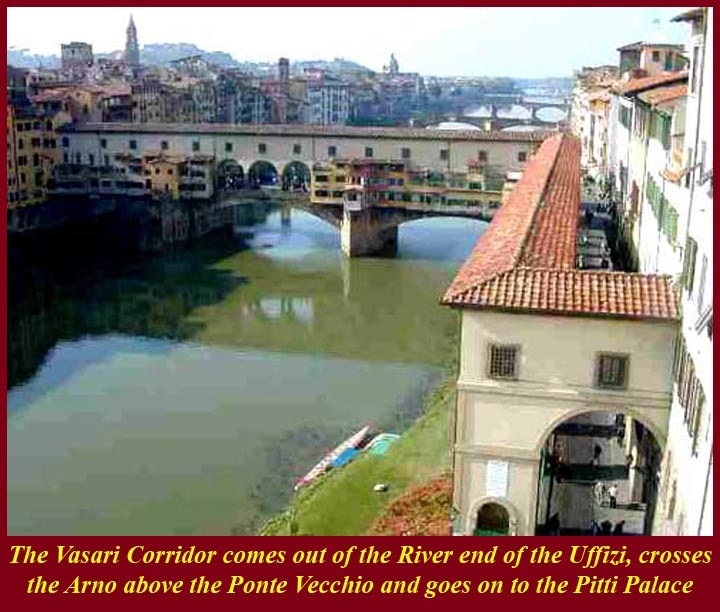

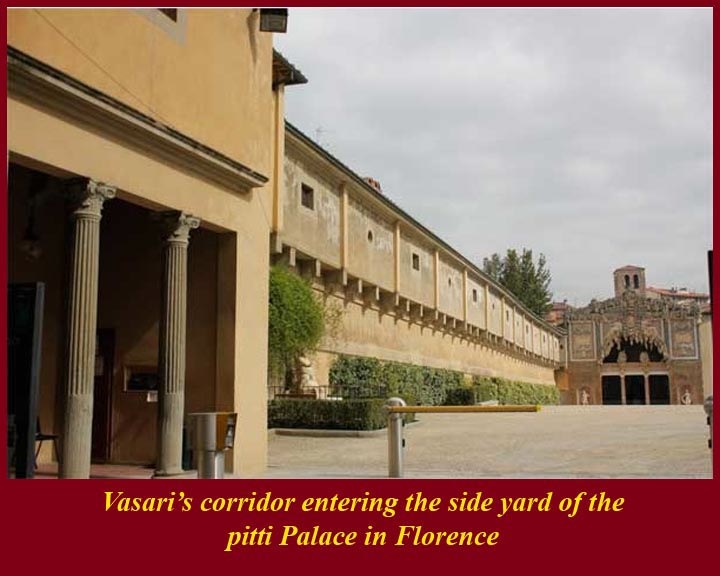

Vasari's reputation as an architect is more durable than his reputation as a painter. He designed and supervised the construction of the Uffizi (a), the name of which indicates its original function as an "executive office building" for the Medici family. His loggia of the Palazzo degli Uffizi by the Arno opens up the vista at the far end of its long narrow courtyard, a unique piece of urban planning that functions as a public piazza, and which, if considered as a short street, is the unique Renaissance street with a unified architectural treatment. The view of the Loggia from the Arno reveals that, with the Vasari Corridor (b through f), it is one of very few structures that line the river which are open to the river itself and appear to embrace the riverside environment.

The Corridor is a long passage that passes over the Arno River on top of the Ponte Vecchio connecting the Palazzo Vecchio and the Uffizi with Palazzo Pitti on the other side of the river. The interior walls of the Corridor are lined with hundreds of self portraits of 15th through 20th century artists including Vasari's own self-portrait.

Rome eventually caught up in art and architecture:

(a few examples: there will be separate units on art and on architecture later.)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0209-ColonnaGalleria.jpg

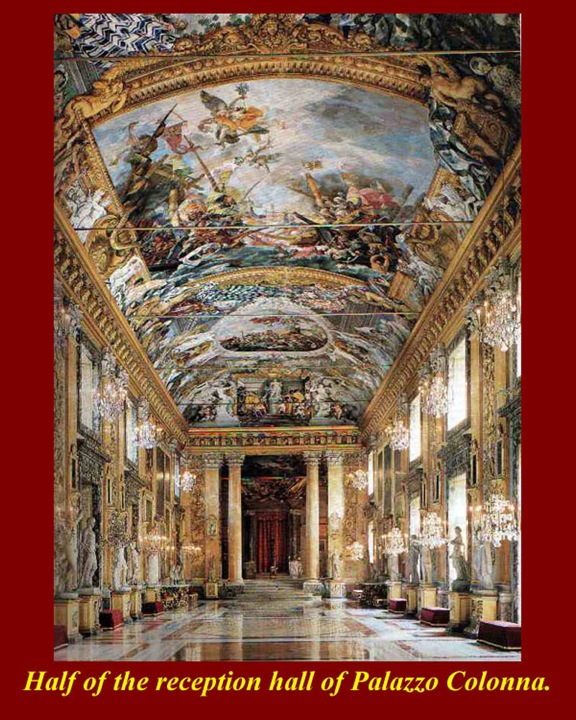

Galleria Colonna in Palazzo Colonna, Rome -- The Colonna fought for centuries with the Orsini for power in Rome. The Orsini, headquartered in the Torre Milizie bombarded the nearby Colonna tower until it collapsed, but the Orsini regrouped and drove out the Orsini. Later the Colonna built Palazzo Colonna which includes this great hall, which is now known as the Galleria Colonna. The Galleria is open to the public only on most Saturday mornings, and it along with two monumental gardens can be rented as a venue for "great events". (See http://www.galleriacolonna.it/ -- click on the red, white, and blue icon in the lower right corner for English language.)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0210-Campidoglio.jpg

Michelangelo's Campidoglio -- Michelangelo designed the Campidoglio for Pope Paul III Farnese. The project was started in 1538, but little was completed before Michelangelo's death in 1564. Its buildings were completed in the 1600s, but the pavement designed for the piazza was only completed was not finished until the 20th century (and then in reverse -- white where Michelangelo had specified black and black where he wanted white. See

http://www.greatbuildings.com/buildings/Piazza_del_Campidoglio.html and http://www.aviewoncities.com/rome/piazzadelcampidoglio.htm or see GOOGLE for about 114,000 more images.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0211-GiambolognaVenus.jpg

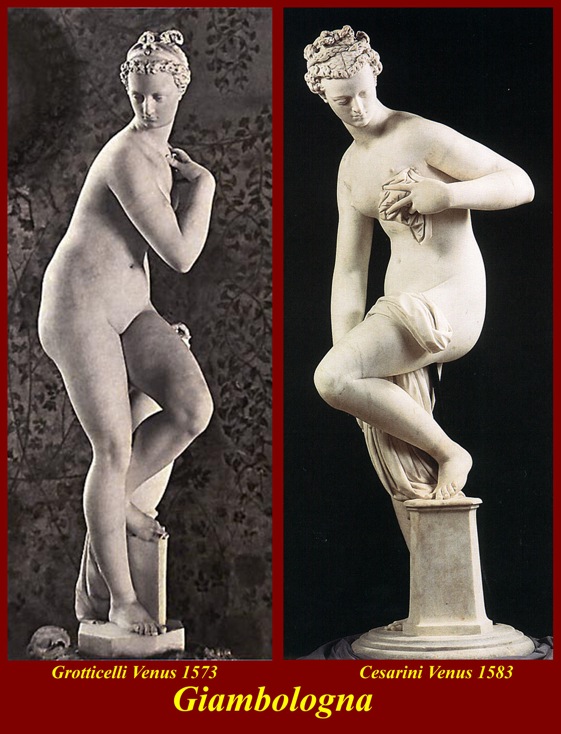

Giambologna's Grotticelli Venus and his Cesarini Venus. See http://www.mmdtkw.org/VGiambolognaVenus.html and http://www.mmdtkw.org/VGiambolognaVenusBrochure.html

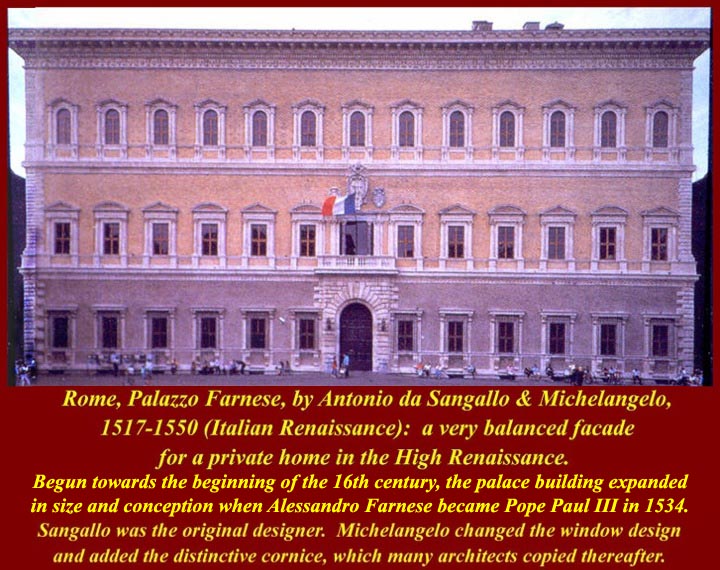

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0212-PalFarnese.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0213-LoggiaFarnese.jpg

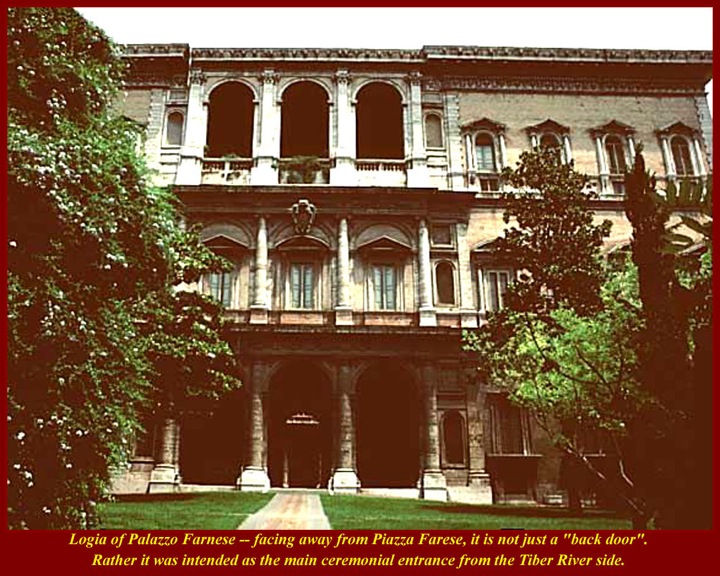

Palazzo Farnese and the Loggia of Palazzo Farnese. See http://www.romeartlover.it/Vasi73.htm.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/RenRom0215VillaMedici.jpg

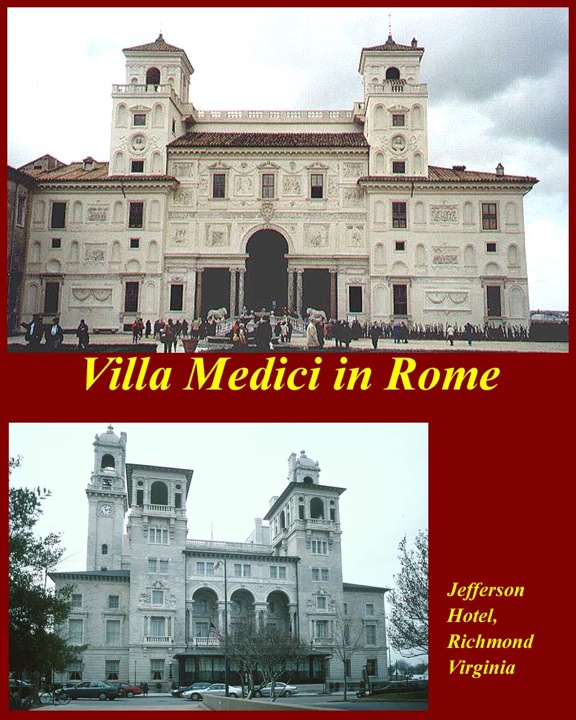

The construction of the Villa Medici in Rome memorialized a change of venue for the headquarters of Medici influence in Italy. Rather than contend with the Popes, Lorenzo the Magnificent decided that his son and stepson would become the Popes. The Medici did not stop their activities in Florence, but rather moved their headquarters to Rome to bolster their position in Florence. The Medici remained in Florence until the last Medici scion Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici, Electress Palatine; Duchess of the Palatinate-Neuburg, of Jülich and Berg, of Cham and the Upper Palatinate, Countess of Megen died in 1743 and left the Medici collections to the Tuscan state. The Florentine Medici name disappeared, but by that time Medici women had married into all the ruling families in Europe. The name died, but Medici blood still flows in the veins of European royalty.

The "villa" Medici actually is the whole of the large architectural complex centered on the a Rome family residence, whose gardens are contiguous with the larger Borghese "villa", on the Pincian Hill next to Santa Trinità del Monti in Rome. The Villa Medici, founded by Ferdinando I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, has housed the French Academy in Rome since 1803. A musical evocation of its garden fountains features in Ottorino Respighi's Fontane di Roma. In ancient times, the site of the Villa Medici was part of the gardens of Lucullus, which passed into the hands of the Imperial family with Messalina, the third wife of Claudius, who was murdered in the villa.

The upper image, above, was the formal entrance to the Villa in the Renaissance. The "back door" that faces Viale della Trinita del Monti is now the entrance to the French Academy. The lower image is the architectural copy, the Jefferson Hotel in Richmond, Virginia.

For information on the Villa Medici, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_Medici and http://www.villamedici.it/ (French and Italian only). For information on Valaria Messalina, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valeria_Messalina.