Monists, monasticism, monasteries, ordersClick on small images and links below to go to larger images for Unit 5

Note: some words on this page were word-processed in letters of the Greek alphabet. I can't guarantee that your computer/web browser will read them.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0500AsianMonasteries.jpg

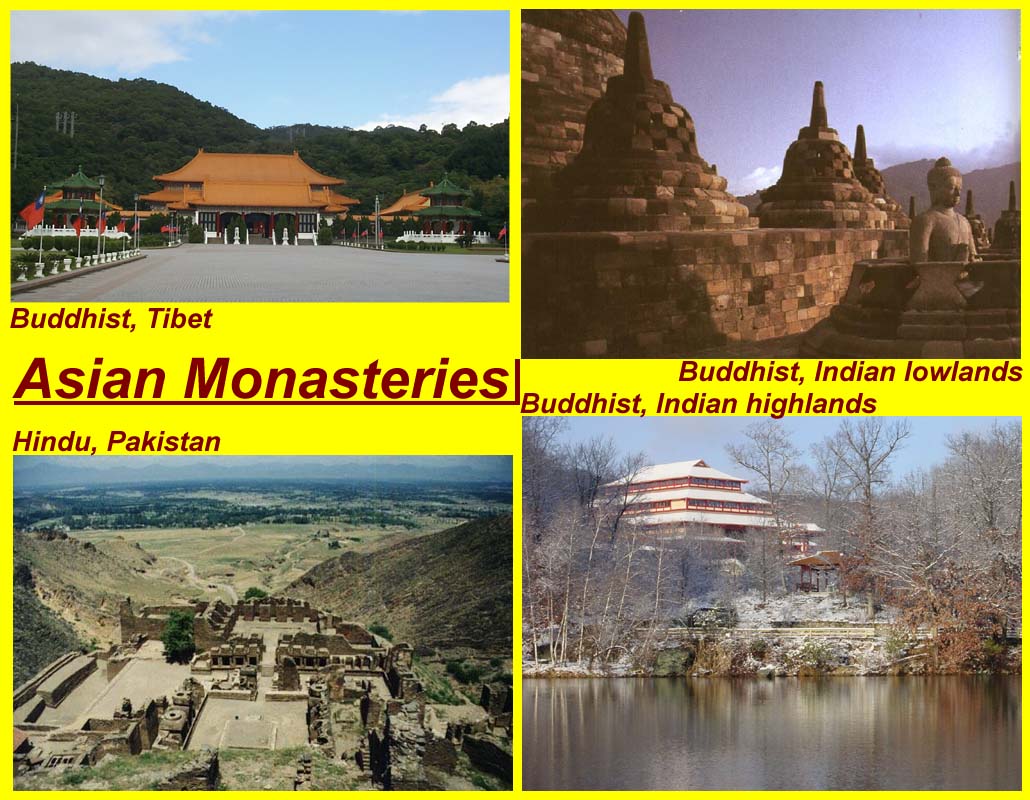

The earliest known form of monastic communities was that of itinerant Buddhist monks who lived communally and traveled together during the south Asian rainy season. That gradually evolved into year-round communal living.

Monastery (plural: monasteries) denotes the building, or complex of buildings, that houses a room reserved for prayer (e.g. an oratory) as well as the domestic quarters and workplace(s) of monastics, whether monks or nuns, and whether living in community or alone (hermits). [Hermits were also called "monists", so a "monastery" was a place where a group of monists could live together -- yes, it's contradictory.]

Cenobitic (also spelled cœnobitic, koinobitic) monasticism is a monastic tradition that stresses community life. Often in the West, members of the community belongs to a religious order, and the life of cenobitic monks is regulated by a religious rule, a collection of precepts. The older style of monasticism, to live as a hermit, is called eremitic; and a third form of monasticism, found primarily in the East, is the skete (a community of Christian hermits following a monastic rule, allowing them to worship in comparative solitude, while also affording them a level of mutual practical support and security).

The English words "cenobite" and "cenobitic" are derived, via Latin, from the Greek words κοινός and βίος (koinos and bios, meaning "common" and "life"). The adjective is κοινοβιακόν in Greek. A group of monks living in community is often referred to as a "cenobium".

Cenobitic monasticism exists in various religions, though Buddhist and Christian cenobitic monasticism are the most common.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0501aaPhilon.jpg

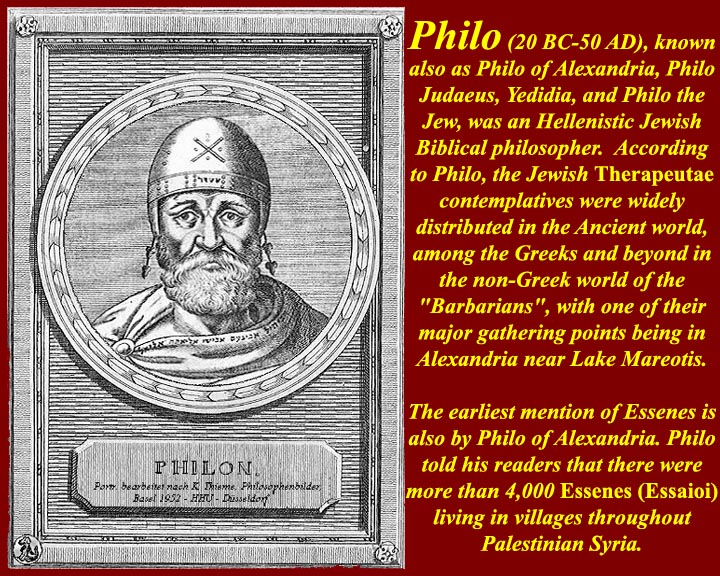

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC – 50 AD): The earliest extant use of the term monastērion is by the first century AD Jewish philosopher Philo (in On The Contemplative Life, ch. III). The Christian monastic tradition appears to have developed from an earlier Jewish form, although that is conveniently ignored in many Christian sources. Approximately 200 years before the birth of Christ, Judaism began to develop monastic sects. The most famous of these (today) were the Essenes, who were mentioned by Philo (and who, some think, are identical or associated with the Qumran sectarians whose library was discovered in 1947 and who gave the world the Dead Sea Scrolls.) Some biblical scholars also suggest that John the Baptist may have been a member of the Essenes. For the most part, the Essenes were religiously fervent men, rebelling against what they saw as the corrupting influences of Roman rule and Hellenization. The Essenes (and other less well known Jewish sects) founded companies of dedicated members removed and isolated from the general populace. These companies were the beginnings of a monastic life that was organized and communal. With the founding of these companies, the Essenes changed monastic life from individual ascetics living eremitic (solitary) lives, to groups of individuals living a cenobitic (communal) life. Rules of behavior, prayer and structure of the community were formalized. Work filled the day and 1/3 of the night was to be devoted to study and meditation.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0501abKhirbetQumran.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0501acQumranChronology.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/medRom0501adQumranSitePlan.jpg

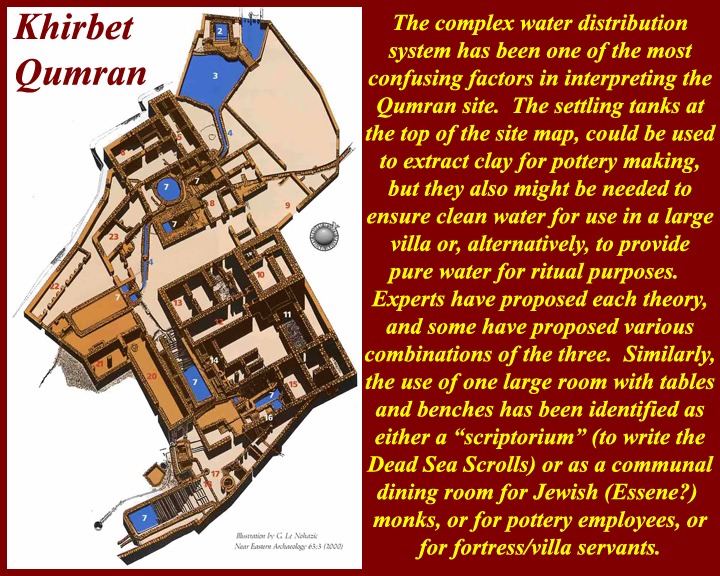

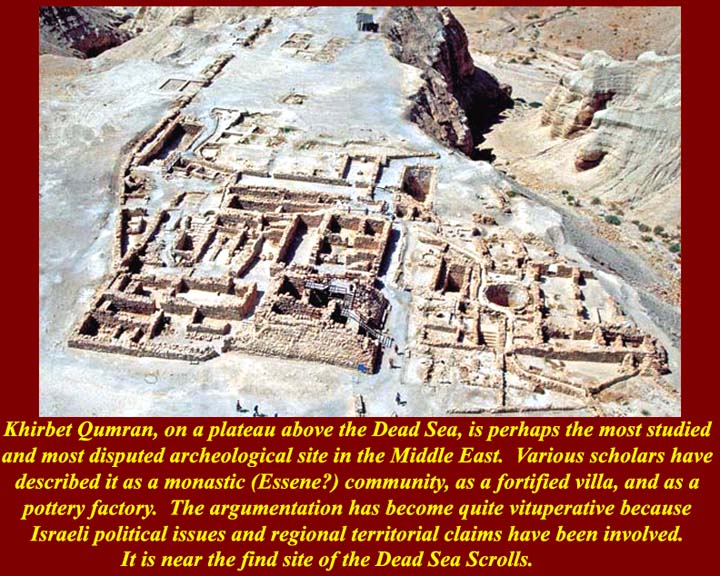

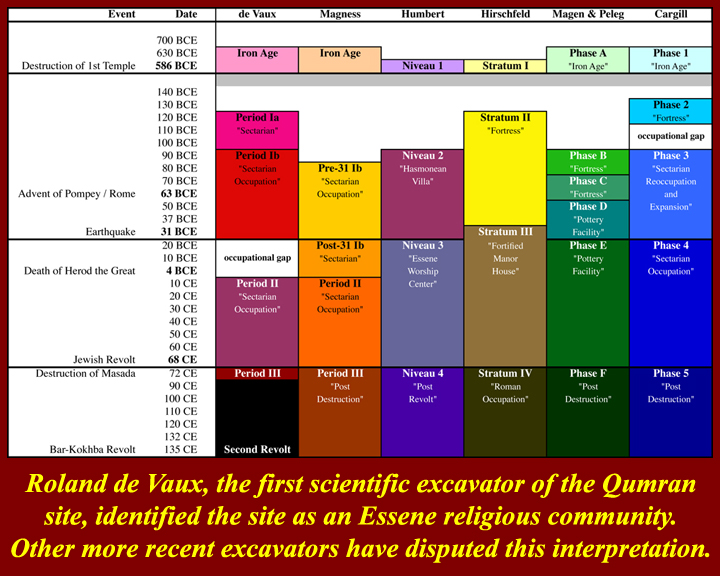

Qumran -- famous monastery, or maybe not.

Khirbet Qumran is the modern Arabic name (also used by Israelis) for a set of ruins and a cemetery at the northern end of the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in nearby caves. The precise nature of the Qumran community is vigorously debated; the three commonly advocated theories are that it was (1) a monastic community (possibly Essenes), or (2) a pottery factory with quarters for the management and workers, or (3) a large fortified agricultural villa, also with quarters. The monastic theory is based primarily on interpretation of some of the Dead Sea Scrolls and on a putative connection between the Scrolls and the Qumran community. None of the three theories are airtight. There are millions of Internet sites that have something to say about Qumran and about the Dead Sea Scrolls. When reading any of these web sites, remember to be doubtful about the accuracy and the motivation of any site that makes absolute statements (for example, about what was there, about who occupied the Qumran ruins, about what the Dead Sea Scrolls mean, or about how the Scrolls were connected with the occupants of Qumran).

For more information on Qumran, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qumran and any of the more that 3.5 million Internet sites that mention Qumran.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0501AnthonyofEgypt.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0502aAntonyBuriesPaul.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0502bAnthonyPaulMonasts.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0502bbAnthonyEgypt.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0502cAnthonyEgy.jpg

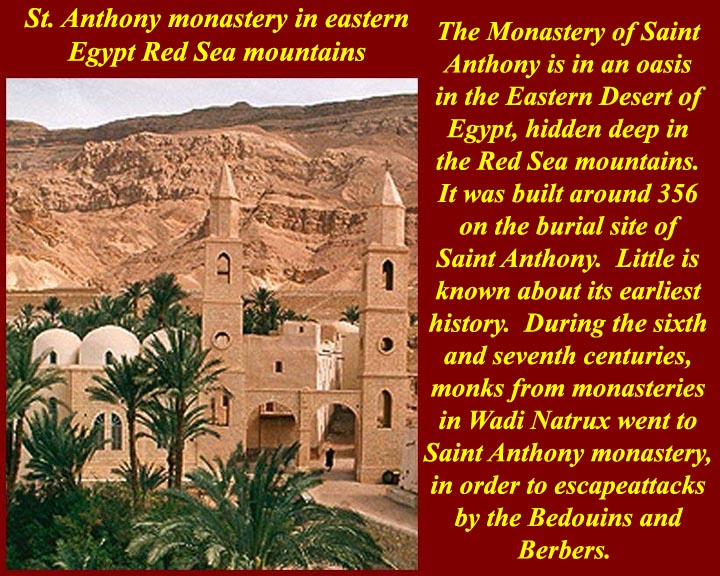

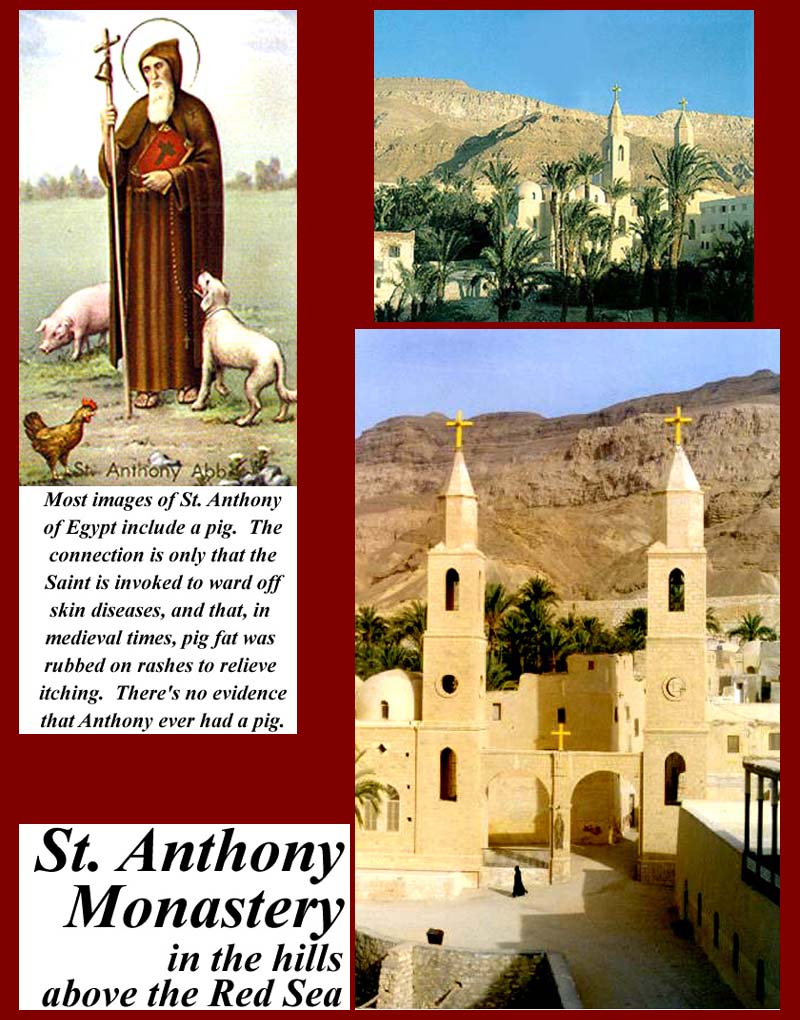

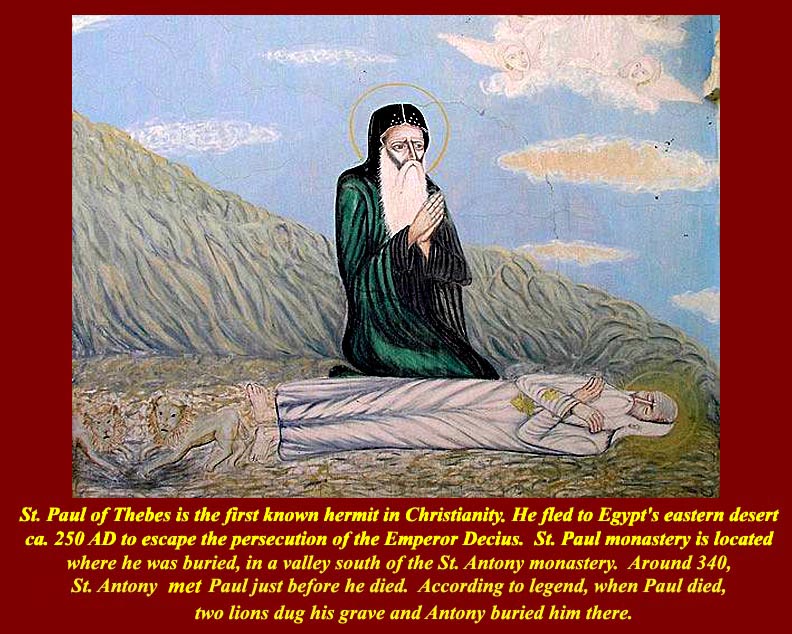

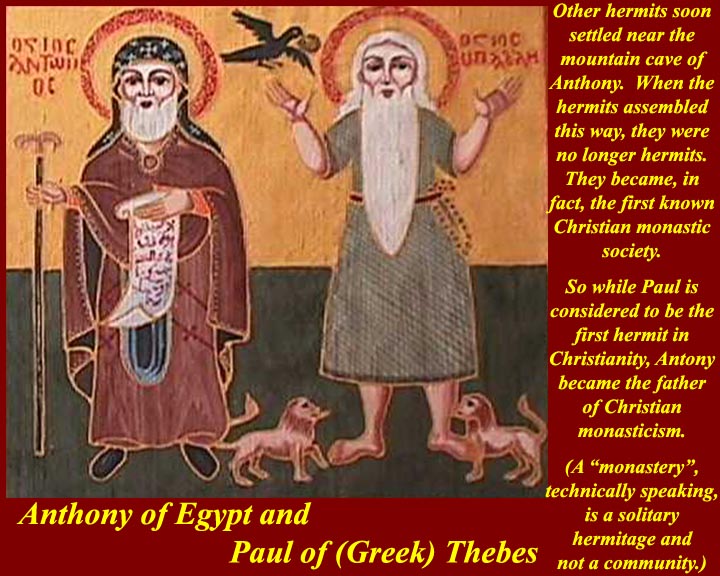

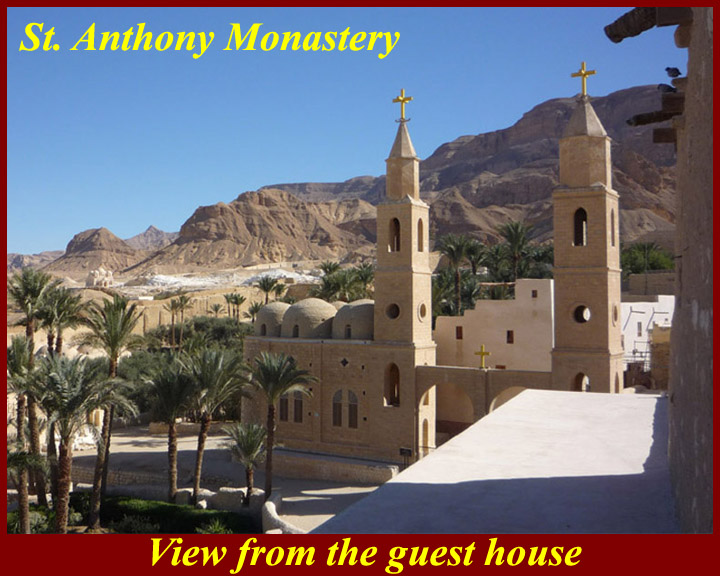

Origin of Christian Monasticism: Christian monastics usually dates their origin to Saint Anthony of Egypt, although they acknowledge that there were earlier communities, which were apparently former Jewish monasteries in which the monks had been converted to Christianity. (Some of these were in the Negev Desert in Israel, in the Sinai, and near the ancient Roman road between Jerusalem and Jericho, at some of which locations Christian monasteries still exist.) What distinguishes Anthony of Egypt and the monastery he is said to have founded are the fact that we know the Christian founder, and we have accounts of his Christian monastic "rule" (the directives for how community members should live) from which Western Christian monastic rules are said to have evolved. Anthony was said to have met and eventually buried St. Paul of Thebes (fl. 3rd century), who was said to have been the first Christian hermit. The St. Anthony monastery in Egypt's eastern desert has for centuries been a pilgrimage and (more recently) a tourist destination. The supposed site of Paul's hermitage is a few miles away.

For information on Anthony and Paul and the St. Anthony monastery, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_the_Great

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monastery_of_Saint_Anthony

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_of_Thebes

http://www.voskrese.info/spl/jer-paul.html

There were numerous monasteries contemporary with that of Anthony at Egyptian sites near the Nile and in the Egyptian eastern and western deserts, to some of which monasteries that exist today trace their origins -- for example the four existing monasteries in Wadi Natrun (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wadi_El_Natrun), which are now on the itinerary of many tourists who travel by car between Cairo and Alexandria, Egypt.

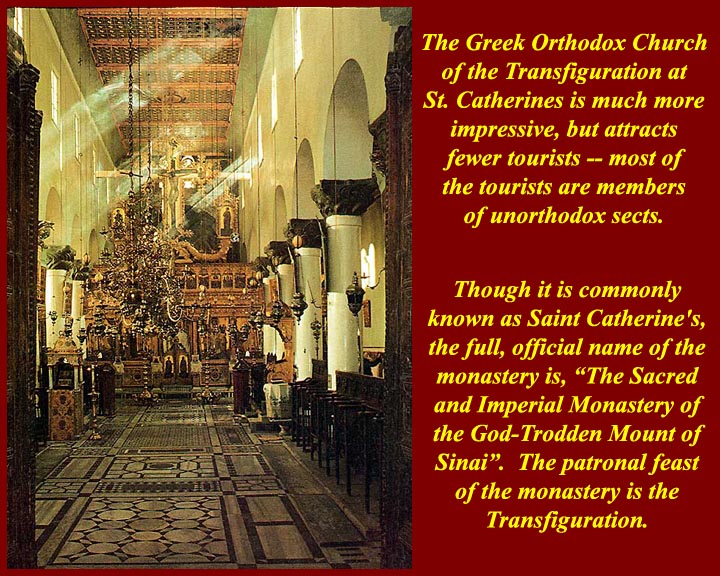

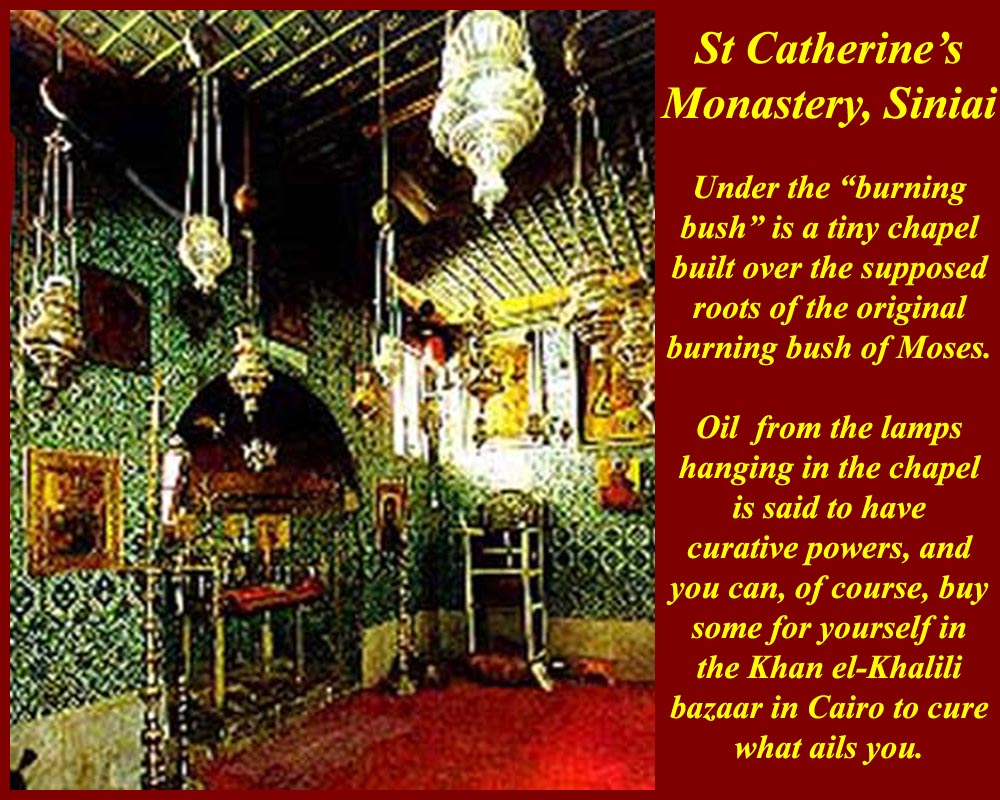

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0503aCatherinesMonastery.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0503bBurningBush.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0503cSiniaiCatherine.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0503dCatherinesTransfiguration.jpg

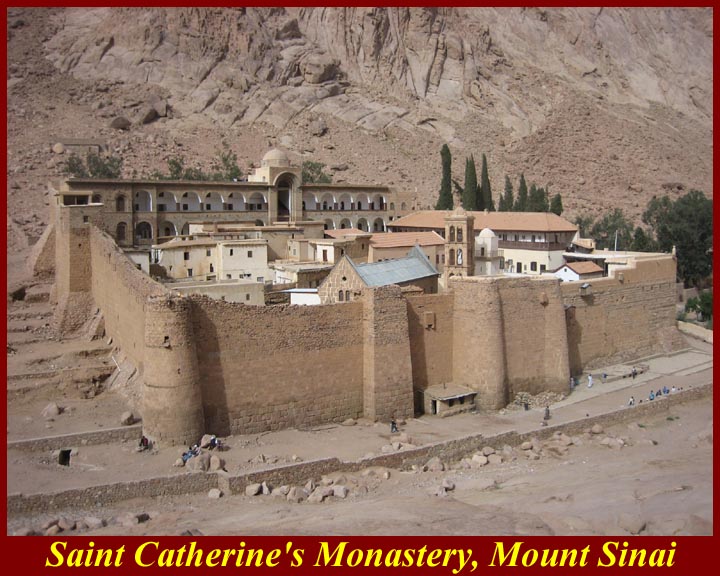

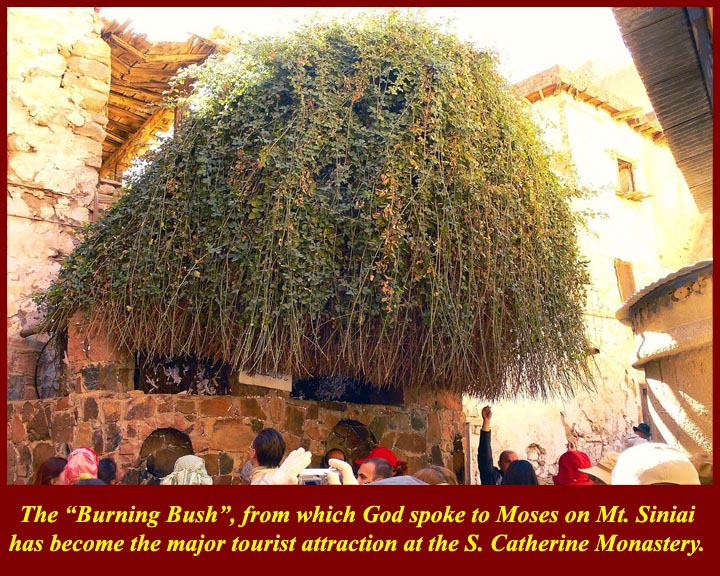

The St. Catherine monastery is in the Sinai Desert and is said to be at the site of the "Burning Bush". The burning bush is an object described by the Book of Exodus (3:1-21) as being located on Mount Horeb; according to the narrative, the bush was on fire, but was not consumed by the flames, hence the name. In the narrative, the burning bush is the location at which Moses was appointed by God to lead the Israelites out of Egypt and into Canaan. (The chapel of the Burning Bush, along with a bush, is still shown to tourists.)

The Hebrew word used in the narrative, which is translated into English as bush, is seneh. Seneh refers in particular to brambles; seneh only appears in two places in the bible both of which describe the burning bush. It is possible that the reference to a burning bush (Seneh) is based on a mistaken interpretation of "Sinai", a mountain described by the Bible as being on fire, and some scholars think that the reference to the burning bush in Deuteronomy, in particular, might be a copyist's error, and may perhaps originally have been a reference to Sinai.

Confusingly, the site that is identified as Mt. Horeb by the presence of the Bush is also identified as Mt. Sinai where Moses is said to have receive the Ten Commandments. Biblical scholars get around this problem by saying, with no external evidence, both names refer to the same place.

For information on the St. Catherine Monastery, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Catherine's_Monastery,_Mount_Sinai, or

http://www.touregypt.net/catherines.htm.

The monastery is the central feature of a protected area designated by the Egyptian government as a National Park.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0503eWadiKelt.JPG

The Monastery of St. George "the Chozebite" (i.e., from Echzib, north of Acre = modern Akko) is beside the Wadi Qelt opposite the ancient Roman road that connected Jerusalem (the Roman Colonia Aelia Capitolina, founded by Hadrian) with Jericho. The monastery is only accessible on foot. It's an arduous trek down one side of the Wadi and back up the other, and you have to reverse the process on the way out. What you see now on the outside dates from the beginning of the 20th century, but the inside, including the crypt (bones of many,many monks going back for centuries, maybe millennia), is ancient.

For more information, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wadi_Qelt.

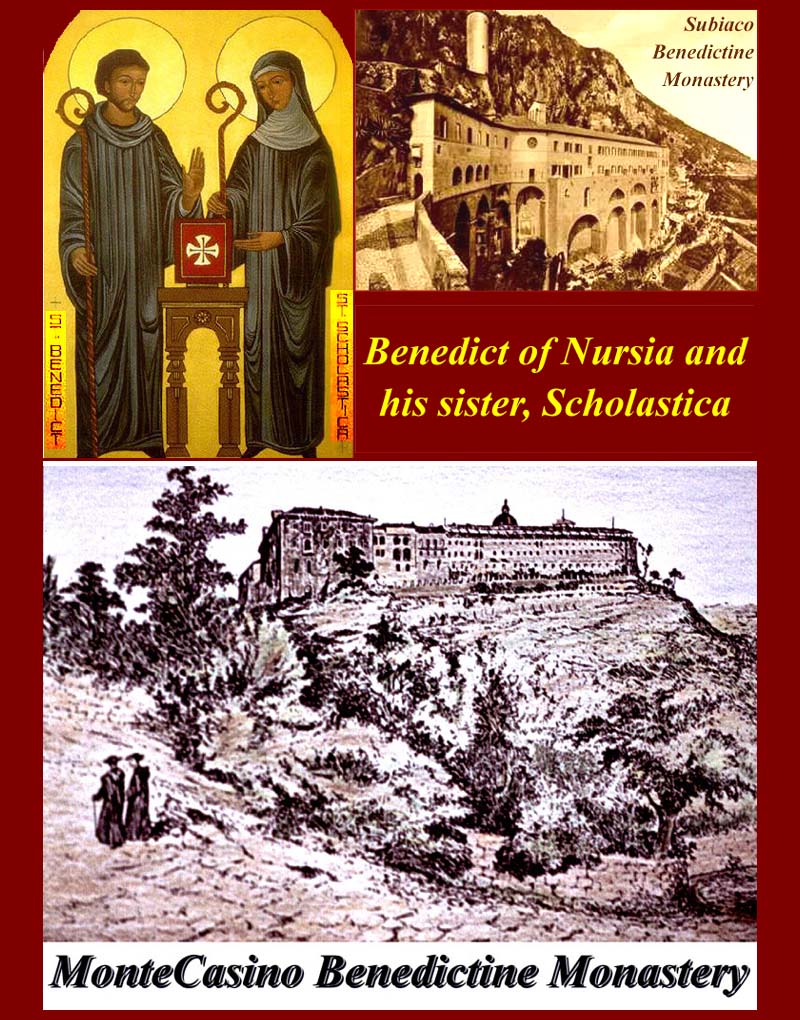

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0504BenedictNursia.jpg

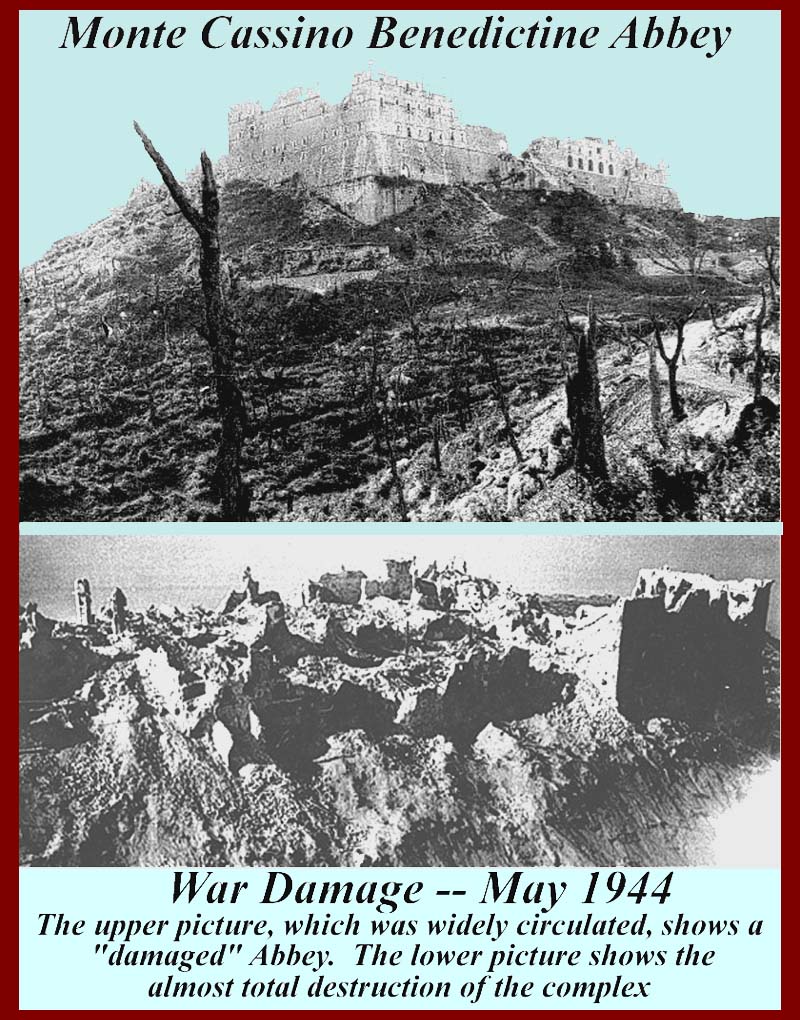

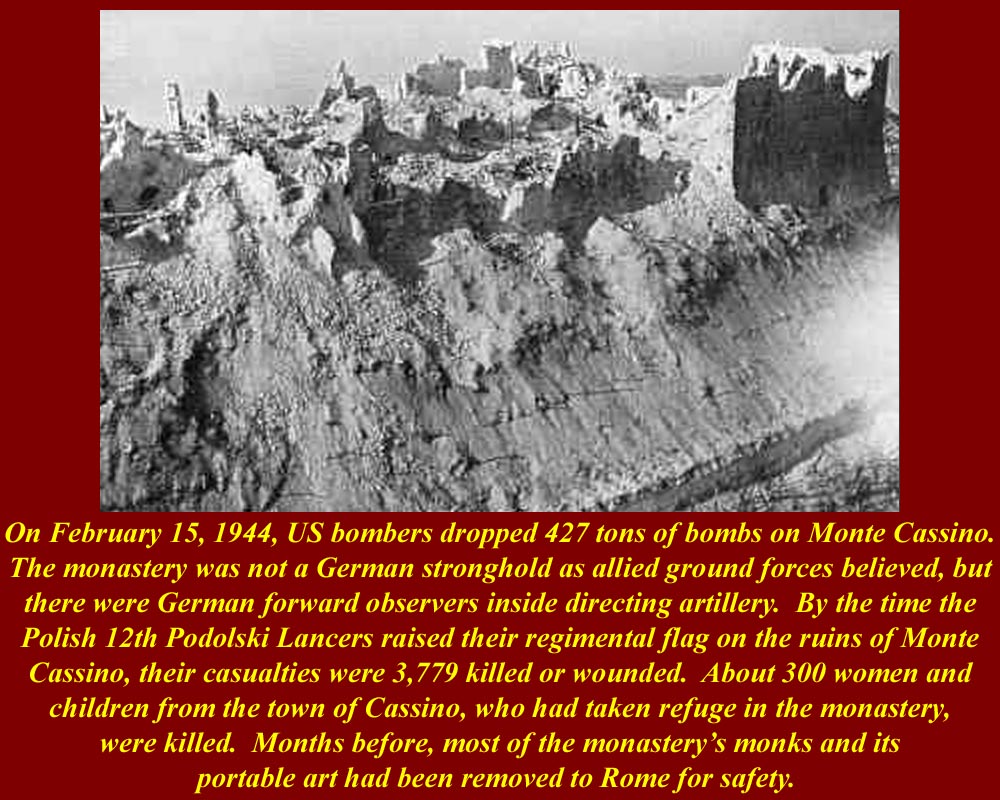

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0505aCassinoWarDamage.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0505bMonteCasino.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0505cmonte_cassino_aerial.JPG

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0505dcassino_aerial.JPG

Benedict of Nursia (480-547 AD) and his Monastery at Mont Cassino -- Benedict of Nursia founded twelve communities for monks at Subiaco, about 40 miles to the east of Rome, before moving to Monte Cassino in the mountains of southern Italy. There is no evidence that he intended to found a religious order. The Order of St Benedict is of modern origin and, moreover, not an "order" as commonly understood but merely a confederation of autonomous congregations.

Benedict's main achievement is his "Rule", containing precepts for his monks. It is heavily influenced by the writings of John Cassian (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Cassian), and shows strong affinity with the Regula Magistri or Rule of the Master, an anonymous sixth-century collection of monastic precepts. But Benedict's rule also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation and reasonableness (ἐπιείκεια, epieikeia), and this persuaded most religious communities founded throughout the Middle Ages to adopt it. As a result, the Rule of Benedict became one of the most influential religious rules in Western Christendom. For this reason Benedict is often called the founder of western Christian monasticism. There are Roman Catholic, Anglican, and independent "Benedictine" communities.

For more information on Benedict, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedict_of_Nursia and http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02467b.htm. Benedict's Rule is on line in several places -- just search for Benedict and rule. Benedictine organization is expounded at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedictine_Confederation.

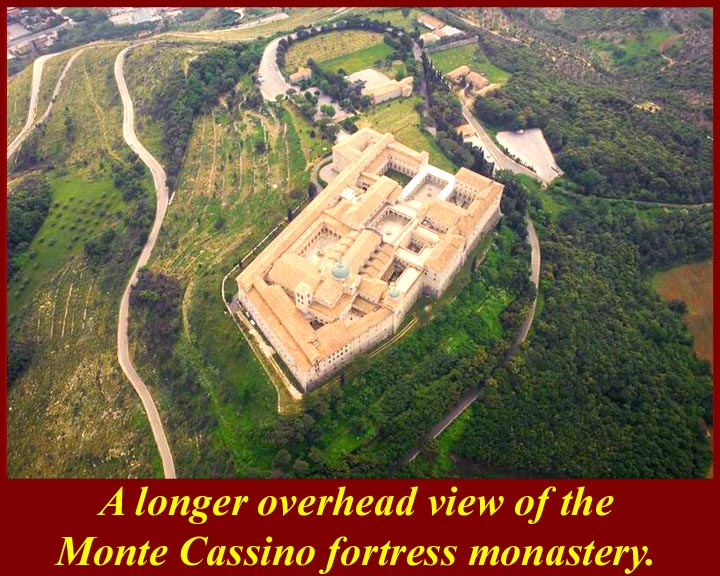

The Monastery: Monte Cassino is a rocky hill about 130 km (80 miles) southeast of Rome, Italy, c. 2 km to the west of the town of Cassino (the Roman Casinum having been on the hill) and 520 m (1,706.04 ft) altitude.

St. Benedict of Nursia established his first large monastery, the source of the Benedictine "Order", here around 529 AD.

It was the site of Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944. The site has been visited many times by the Popes and other senior clergy, including a visit by Pope Benedict XVI in May 2009. The monastery is one of the few remaining territorial abbeys within the Catholic Church.

According to Gregory the Great's biography of Benedict the monastery was constructed on an older pagan site, a temple of Apollo that crowned the hill. The biography records that the area was still largely pagan at the time and Benedict's first act was to smash the sculpture of Apollo and destroy the altar. He then reused the temple, dedicating it to Saint Martin, and built another chapel on the site of the altar dedicated to Saint John the Baptist. Archaeologist Neil Christie notes that it was common in such hagiographies for the protagonist to encounter areas of strong paganism. Once established at Monte Cassino, Benedict never left. There he wrote the Benedictine Rule that became the founding principle for western monasticism. It was at Monte Cassino that he reputedly received a visit from Totila, king of the Ostrogoths, perhaps in 543 (the only remotely secure historical date for Benedict), and there he died.

Monte Cassino became a model for future developments, and, of course, Benedict's rule was adopted in monasteries throughout the western world. Unfortunately its protected site has always made it an object of strategic importance. It was sacked or destroyed a number of times -- the events form part of the text at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monte_Cassino. The abbey's own web site is at

http://www.officine.it/montecassino. For the World War II battle of Monte Cassino, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Monte_Cassino or approximately 150 thousand other Internet sites.

Cluny:

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0505fCluny.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0505gCluny.jpg

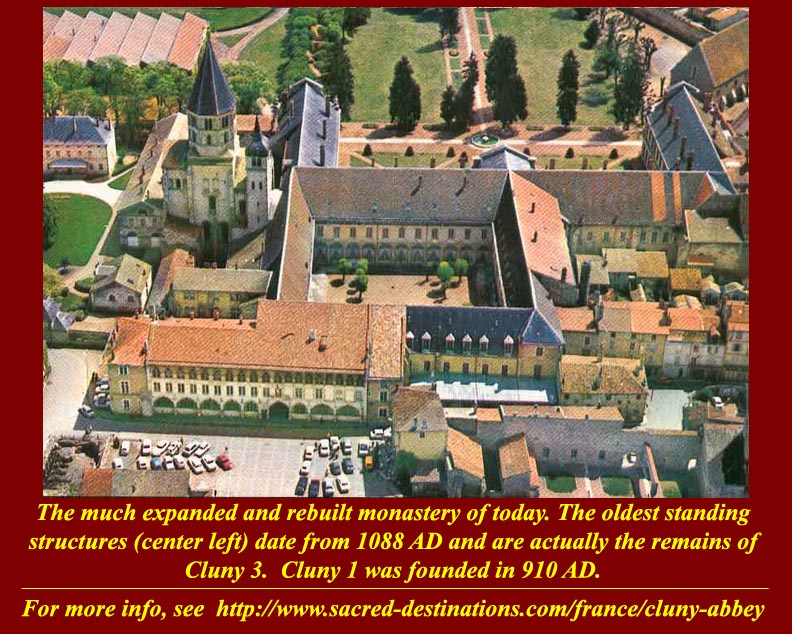

From the tenth century there were successive waves of monastic reform - Cluniac, Cistercian, Mendicant and so forth. The founding of the abbey of Cluny in 910 marked the onset of this period.

Cluny Abbey is a Benedictine monastery in Cluny, department of Saône-et-Loire, France and was built in the Romanesque style.

It was founded in 910 by William I, Count of Auvergne, who installed Abbot Berno and placed the abbey under the immediate authority of Pope Sergius III. The abbey and its constellation of dependencies (subsidiary houses) soon came to exemplify the kind of religious life that was at the heart of 11th-century piety. The town of Cluny, in the modern department of Saône-et-Loire in the former province of Bourgogne, in east-central France, near Mâcon, grew round the former abbey, founded in a forested hunting reserve.

The Benedictine order was a keystone to the stability that European society achieved in the 11th century, and partly owing to the stricter adherence to a reformed Benedictine rule, Cluny became the acknowledged leader of western monasticism from the later 10th century. A sequence of highly competent abbots of Cluny were statesmen on an international stage. The monastery of Cluny itself became the grandest, most prestigious and best endowed monastic institution in Europe. The height of Cluniac influence was from the second half of the 10th century through the early 12th. The abbey was sacked and mostly destroyed in 1790 during the French Revolution, and only a small part of the original remains.

The monastery of Cluny differed in three ways from other Benedictine houses and confederations: in its organizational structure, in the prohibition on holding land by feudal service and in its execution of the liturgy as its main form of work. While most Benedictine monasteries remained autonomous and associated with each other only informally, Cluny created a large, federated organisation in which the administrators of subsidiary houses served as deputies of the abbot of Cluny and answered to him. The Cluniac houses, being directly under the supervision of the abbot of Cluny, the autocrat of the Order, were styled priories, not abbeys. The priors, or chiefs of priories, met at Cluny once a year to deal with administrative issues and to make reports. Many other Benedictine houses, even of earlier formation, came to regard Cluny as their guide.

For the ups and downs of the Cluny Abbey, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cluny_Abbey

or http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04073a.htm. For information on the Cluniac Reforms, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cluniac_Reforms.

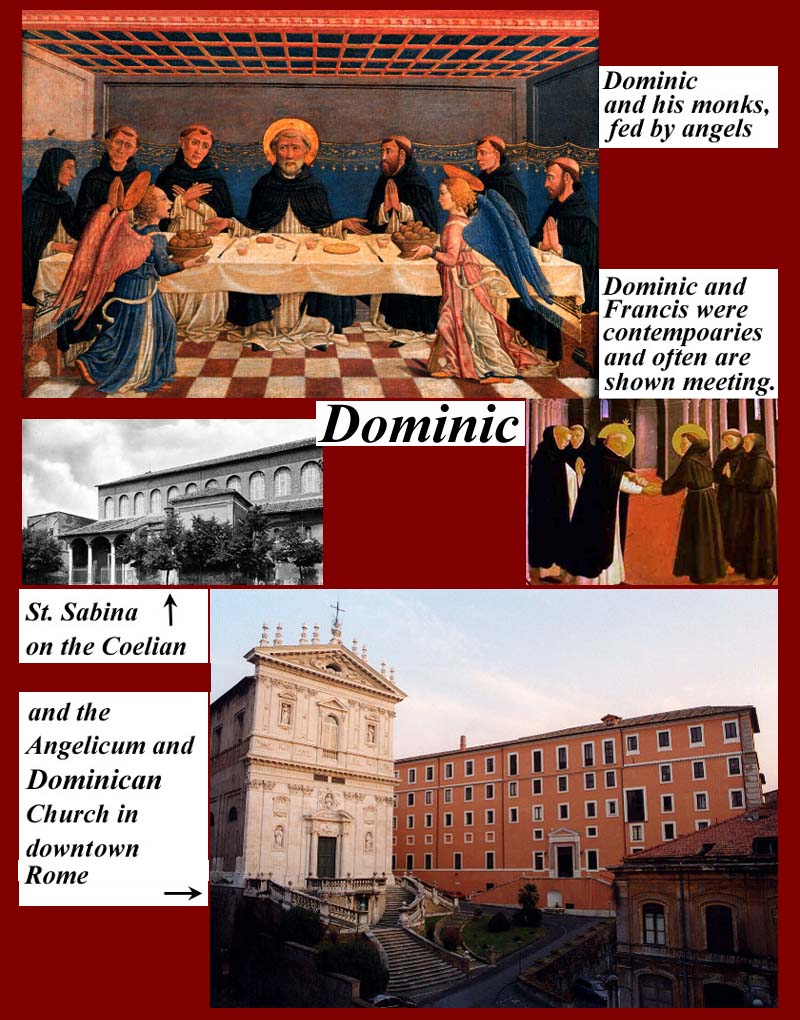

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0506aDominic.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0506Dominic.jpg

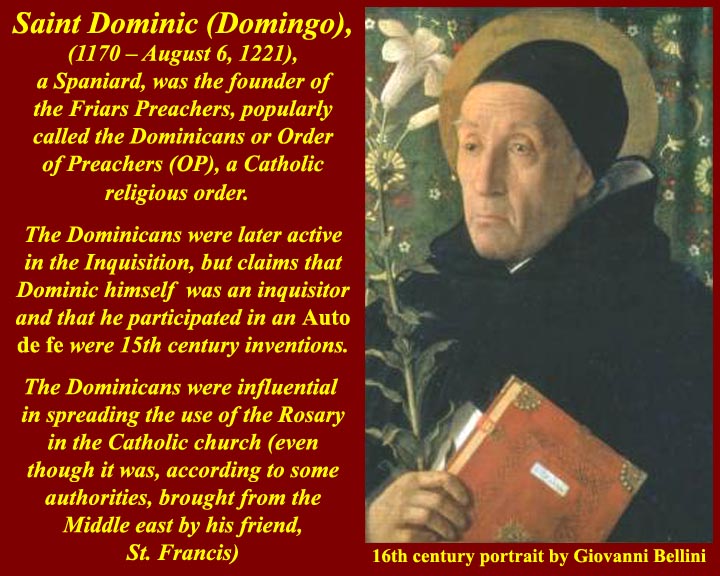

Dominic -- Domingo Félix de Guzmán (1170 – August 6, 1221) was, as can be seen by his name, a Spaniard and was the founder of the Friars Preachers, popularly called the Dominicans or Order of Preachers (OP), a Catholic religious order.

From the Dominican (OP) internet site:

Dominic was born in 1170 in Caleruega, Spain. He received his education in Palencia. News of Dominic's virtues reached the Bishop of Osma, who summoned Dominic and made him a Canon Regular of his church. Lead by Diego de Acebo, the prior of the community, he learned the basics of religious life and contemplation.

Diego became bishop of Osma and invited Dominic to travel with him as he spread the Gospel. Together in 1206, both men offered Pope Innocent III their services to save souls. The pope asked them to go preach to the Cathars of Languedoc. Contrary to the habits of the Cistercians, Dominic and Diego roamed the villages of Languedoc on foot, begging their bread.

Diego soon died, but Dominic continued to preach with the help of a community that had gathered in 1207 and was comprised of women who fled the Cathars and lived the common life in Prouilles. To preach the gospel better, in 1215 Dominic moved on to Toulouse with a few companions that were bound to him by profession. Soon they adopted a rule of life, based on that of St. Augustine [Augustine's "rule" was actually a letter written in 423 and two of his sermons (see http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02079b.htm) -- TKW]. In a bull entitled Religious life, dated December 22, 1216, Pope Honorius III confirmed the Order as an Order of Canons Regular. In 1217 Dominic dispersed the brothers two-by-two to further the preaching mission. To train the best brothers in the preaching, Dominic chose to settle in two large university cities: Paris and Bologna.

Dominic continued to travel between Spain and Rome to establish the Order's foundation. In 1220, delegates of the brothers gathered in Bologna to approve the first constitutions, the first laws governing the operation of the college. Dominic died in Bologna in 1221.

For more information on Dominic, see

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05106a.htm or

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Dominic.

For more on the Dominican order, see

http://www.op.org/ or

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12354c.htm or

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dominican_Order.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0507aaFrasncisClaireGiotto.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0507abAssisiAncientPeriod.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0507aFromBelow.jpg

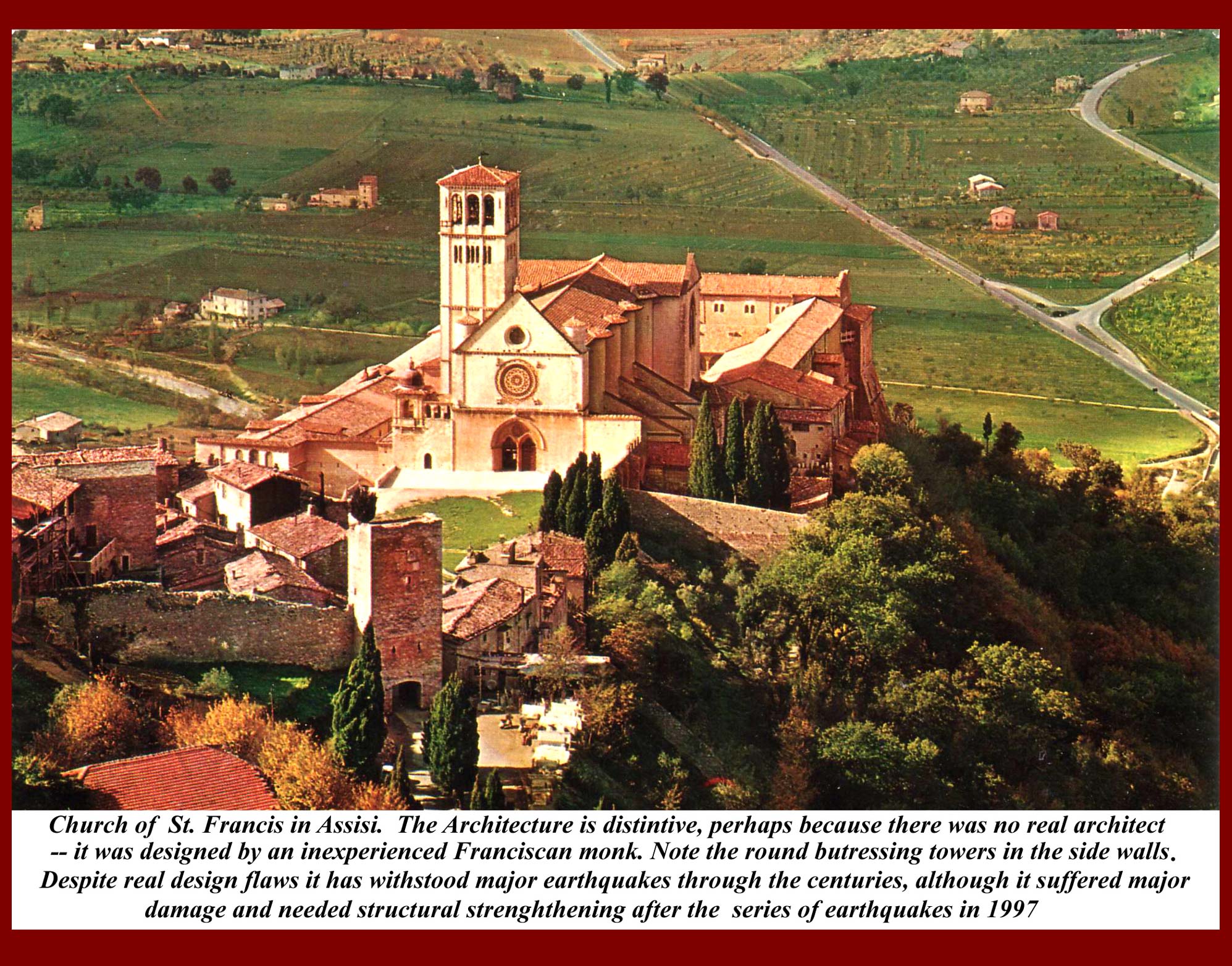

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0507bFromAbove.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0507cAssisiFranciscanComplex.jpg

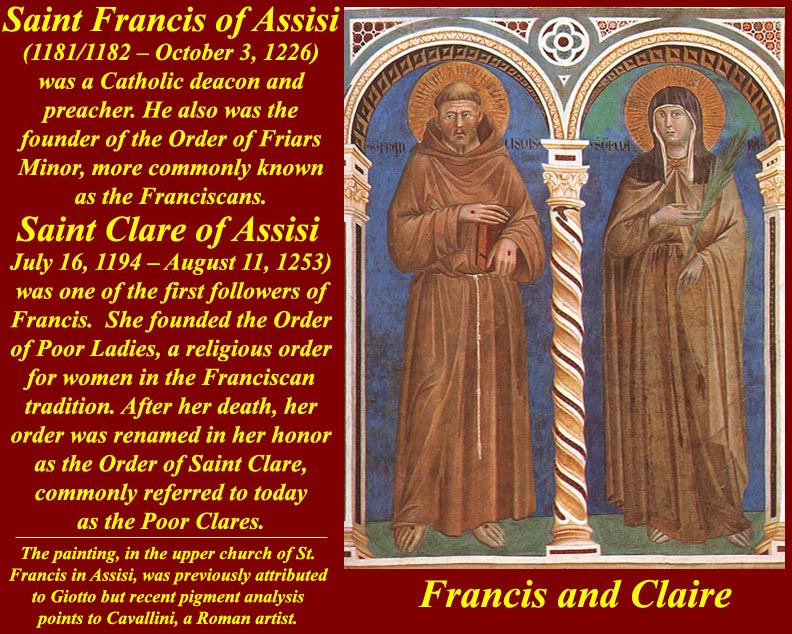

Francis of Assisi (Giovanni Francesco di Bernardone; 1181/1182 – October 3, 1226)[2] was a Catholic deacon and preacher. He also was the founder of the Order of Friars Minor, more commonly known as the Franciscans.

Francis was the son of a well-to-do cloth merchant. A lively, even riotous youth who dreamed of achieving military glory, Francis abandoned his worldly ambitions at the age of 19 while a prisoner of war in Perugia. He thereafter became a mystic who experienced visions of Christ and Mary, composed the first poems in the Italian language about the beauties of nature, and in 1210 founded the famous order of mendicant friars known as the Franciscans. His repudiation of the worldliness and hypocrisy of the church, his love of nature, and his humble, unassuming character earned him an enormous following throughout Europe, posing an unprecedented challenge to the decadent Papacy.

For more information on Francis, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_of_Assisi, or

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06221a.htm.

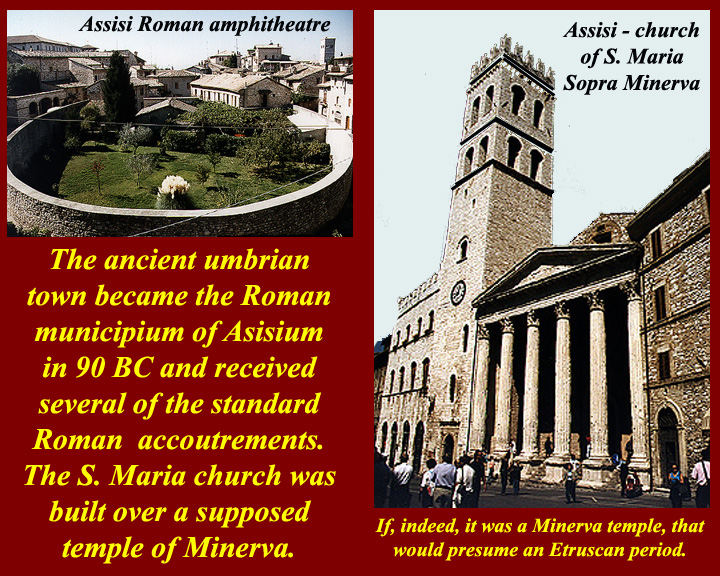

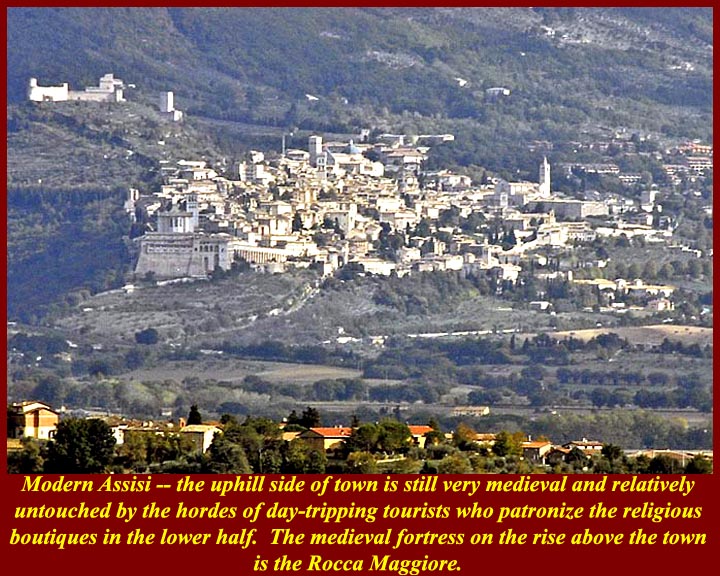

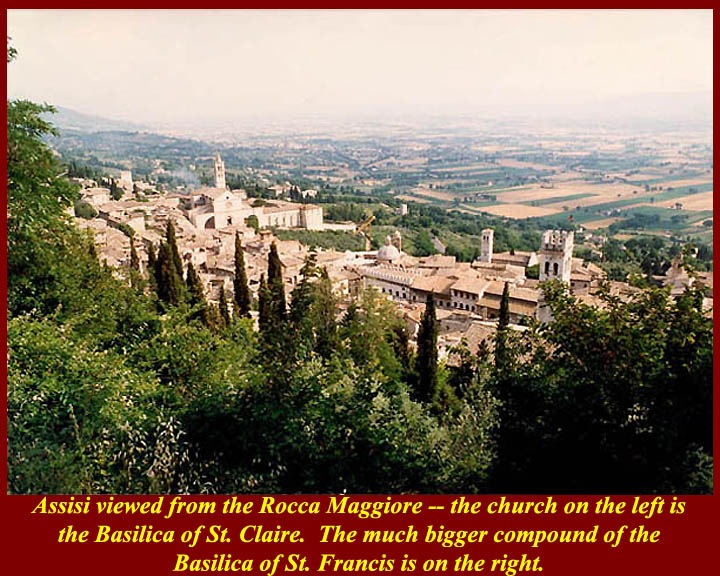

Little is known regarding the original founding of Assisi. One legend tells that the ancient town came into existence around a holy spring that was later venerated by the Etruscans (9th – 5th centuries BC) and, following them, by the Romans. It certainly existed long before Rome was founded; a legend tells that the town was begun by Dardanus 865 years before Rome was founded in 753 BC. Sometime in the 1st century BC, by which time the town was called Asisium, a temple of Minerva, the goddess of art, handicrafts and the professions, was constructed at the sacred spring. But Minerva was originally an Etruscan goddess, and there may well also have been an earlier Minerva temple at the spring. In 238 AD Assisi was converted to Christianity by bishop Rufino, who was later martyred at Costano. During the early Christian era, parts of the temple of Minerva were incorporated into a Christian church (S. Maria sopra Minerva). Eventually, due to one of the region's numerous earthquakes, the sacred spring stopped flowing. After the time of St. Francis, the town was patronized by the popes who sought to capitalize on Franciscan popularity, and it very quickly achieved its current status as a popular destination for religious tourism. Assisi today assiduously maintains it medieval boutique appearance with the church and monastery of St. Francis as its centerpiece.

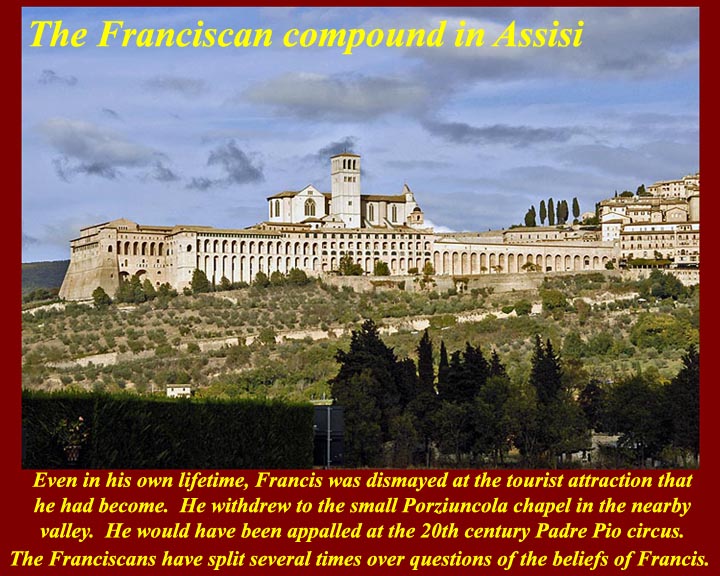

The Franciscans have split several times as factions left to avoid the commercialization of the memory of Francis. That's why there are Greyfriars and brown and Capuchins, etc. Even in his own time, Francis withdrew from Assisi to avoid becoming, himself, a tourist attraction. He spent his last years in the Porziuncola, a small church in the frazione of Santa Maria degli Angeli about 4 kilometers from Assisi.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0507cAssisiFranciscanComplex.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0508FrancisChurAssisi.jpg (high definition)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0509Assisi97Quake.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0509xAssisiEarthquake26Sep97.jpg

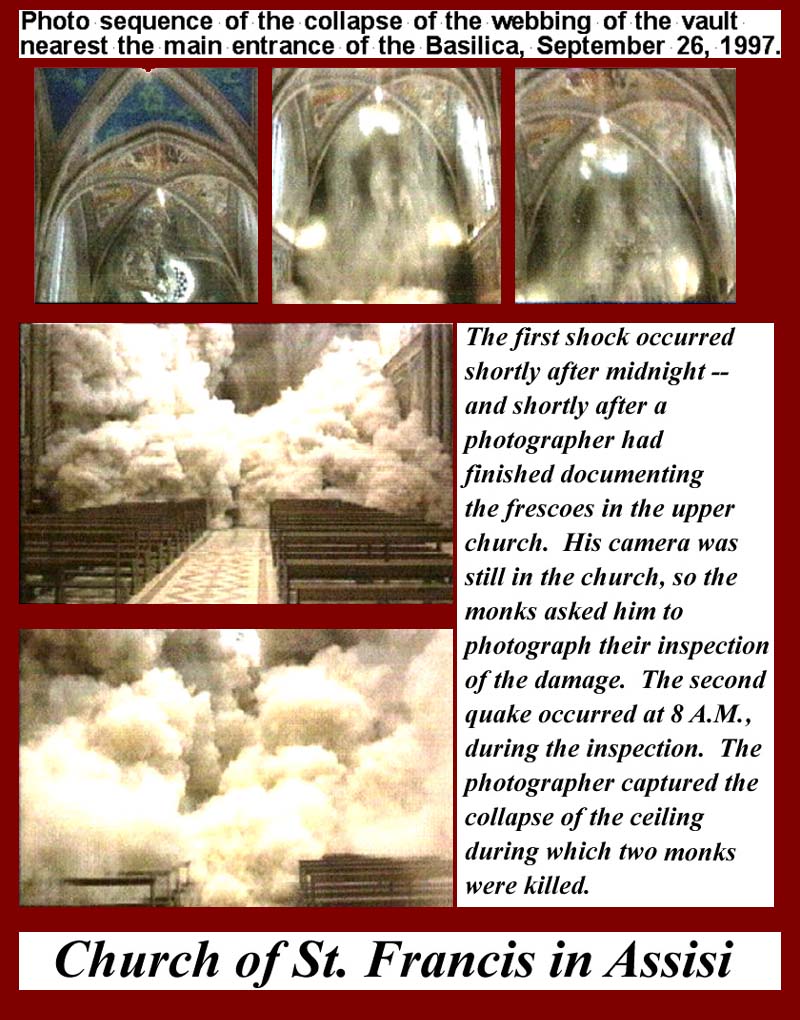

The Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi was decorated at the time of a turning point in Italian art; the Middle Ages was giving way to the Renaissance. Its cycles of frescoes by Lorenzetti, Martini, Cimabue, Cavallini and Giotto are among the icons of Western art. More than a score of earthquakes had rattled the stones of the great Romanesque church in the 800 years since its construction began, but the frescoes remained. On September 26, l997, some were shattered by the worst quakes in Assisi's history. A huge section of the Vault of the Evangelists, including Cimabue's St. Matthew and Giotto's St. Jerome, fell to the floor, killing four people.

The previous afternoon, Ghigo Roli had completed photographic documentation of the vaults, and after midnight he was in the church packing his equipment. At about two AM he stepped outside for a smoke, and at 2:33 the first quake struck bringing down small parts of the ceiling. After daylight, engineers and some of the Franciscans were in the church to assess the damage when the largest tremor struck at 11:43 AM. Cameraman Paolo Antolini was in the Apse of the church, farthest away from the front door when the ceiling near the front door collapsed. His film of the collapse is available on the Internet at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p10zZx2Feu0.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0510DeathFrancis.jpg

Earthquake and art history: The image of the death and apotheosis of Francis is part of the upper basilica fresco cycle of the life of Francis that had been attributed to Giotto by Georgio Vasari. But the earthquake made available small flakes of paint from all the frescoes in the church -- flakes that art historians had coveted but had never been able to get, because you just don't chip away at late medieval proto-renaissance masterpieces.

The fresco cycle of the Life of St. Francis in the Upper Church is one of the most hotly disputed attributions in art history. The documents of the Franciscan Friars that relate to artistic commissions during this period were destroyed by Napoleon's troops, who stabled horses in the Upper Church of the Basilica, and scholars have been divided over whether or not Giotto was responsible for the Francis Cycle. In the absence of documentary evidence to the contrary, it has been convenient to ascribe every fresco in the Upper Church that was not obviously by Cimabue, to Giotto, whose prestige has overshadowed that of almost every contemporary. Some of the earliest remaining biographical sources, such as Ghiberti and Riccobaldo Ferrarese, suggest that the fresco cycle of the life of St Francis in the Upper Church was his earliest autonomous work. However, since the idea was put forward by the German art historian, Friedrich Rintelen in 1912, many scholars have expressed doubt that Giotto was in fact the author of the Upper Church frescoes. Without documentation, arguments on the attribution have relied upon connoisseurship, a notoriously unreliable "science."

Recent technical examinations -- scientific analysis of those small paint flakes -- and comparisons of the workshop painting processes at Assisi and Padua have provided strong evidence that Giotto did not paint the Francis Cycle. There are many differences between the Francis Cycle and the Scrovegni/Arena Chapel frescoes in Padua that are difficult to account for by the stylistic development of an individual artist. It seems quite possible that several hands painted the Assisi frescoes, and that the artists were probably from Rome; the paint samples do match samples from the studio of Roman artist Pietro Cavalini. If this is the case and if the Assisi cycle was painted, as Vasari said, between 1296 and 1304, then Giotto's frescoes at Padua (1305) owe much to the naturalism of the Roman painters.

For information on Giotto, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giotto_di_Bondone and http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/vasari/vasari1.htm.

For Cavallini, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pietro_Cavallini.

For Vasari, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giorgio_Vasari.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0511IgnatiusLoyola.jpg

Ignatius of Loyola (Basque: Ignazio Loiolakoa, Spanish: Ignacio de Loyola) (1491 – July 31, 1556) is way out of our time period, but is included here because he founded a major Catholic religious order.

Ignatius was a Spanish knight from a Basque noble family, a hermit, priest from 1537, and theologian, who founded the Society of Jesus and was its first Superior General. Ignatius emerged as a religious leader during the Counter-Reformation. His devotion to the Church was characterized by unquestioning obedience to everything said by her hierarchy.

After being seriously wounded at the Battle of Pamplona in 1521, he underwent a spiritual conversion while in recovery. De Vita Christi by Ludolph of Saxony (or alternatively, a book of lives of saints) inspired Loyola to abandon his previous military life and devote himself to the Church, following the example of spiritual leaders such as Francis of Assisi. While at the shrine of Our Lady of Montserrat in March 1522, he had a spiritual/emotional experience said to have been a vision of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus. (This was one of several visions in the course of his recovery and later while fasting.). He went to Manresa, where he began praying for long periods of time, often in a nearby cave, while formulating the fundamentals of the Spiritual Exercises. In September 1523, Loyola reached the Holy Land to settle there, but was sent back to Europe by the Franciscans, apparently because he had a relapse in his recovery from his war wound..

Between 1524 and 1537, Ignatius studied theology and Latin in Spain and then in Paris. In 1534, he had arrived in the latter city during a period of anti-Protestant turmoil which forced John Calvin to flee France. He and a few followers bound themselves by vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. In 1539, they formed the Society of Jesus, approved in Rome in 1540 by Pope Paul III (Ignatius and his companions made their formal professions in 1541.) Paul III approved Ignatius' Spiritual Exercises in 1548. Ignatius also composed the Constitutions of the Society. He died in July 1556.

The Jesu church in Rome was built by his successors around the small chapel that the pope had given Ignatius at a crossroad in the city's red light district. The Jesu is completely contrary to the simple and poor life that Ignatius envisioned. It grew from the conviction, which Jesuit missionaries brought back from the far east that, their churches must be at least as large and ornate as the churches.temples of their religious rivals if they were to attract a congregation.

For information on Ignatius, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignatius_of_Loyola or

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07639c.htm.

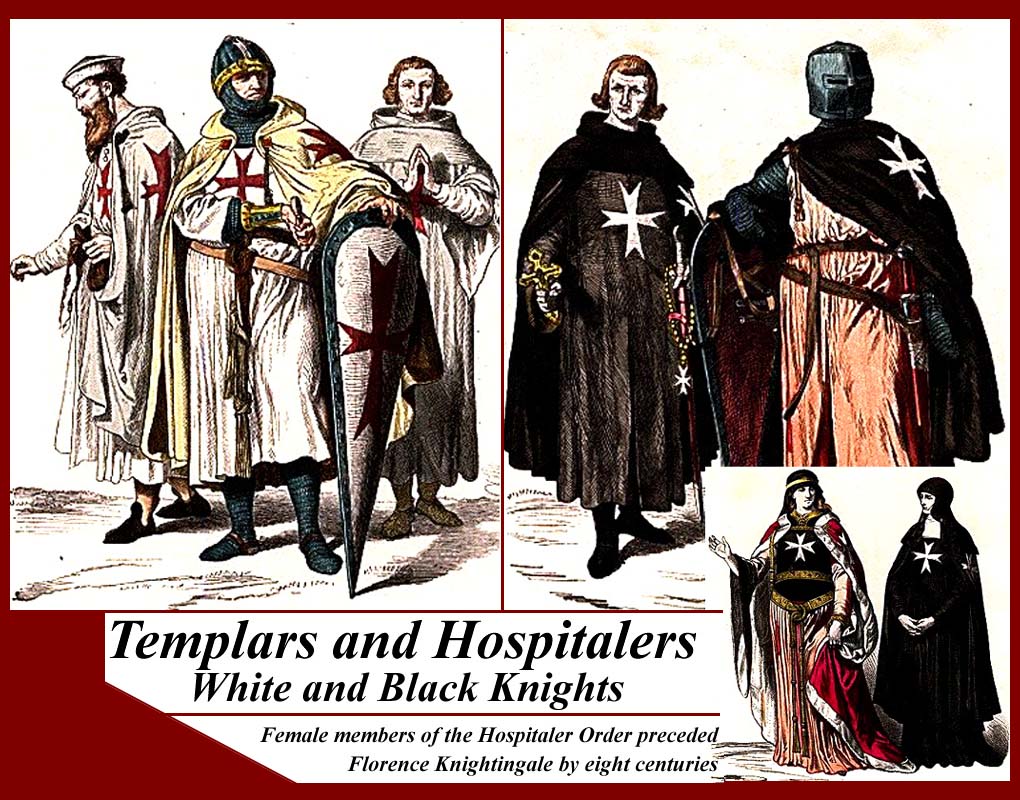

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0512MilitaryOrders.jpg

The Templar and Hospitaller knights were members of military orders that originated in the middle east during the crusades. Like members of contemporary religious orders they took vows related to their service.

Templars: the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Latin: Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Solomonici), commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple (French: Ordre du Temple or Templiers) or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders. The organization existed for approximately two centuries in the Middle Ages.

Officially endorsed by the Roman Catholic Church around 1129, the Order became a favoured charity throughout Christendom, and grew rapidly in membership and power. Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades. Non-combatant members of the Order managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom, innovating financial techniques that were an early form of banking, and building many fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land.

The Templars' existence was tied closely to the Crusades; when the Holy Land was lost, support for the Order faded. Rumors about the Templars' secret initiation ceremony created mistrust, and King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Order, took advantage of the situation. In 1307, many of the Order's members in France were arrested, tortured into giving false confessions, and then burned at the stake. Under pressure from King Philip, Pope Clement V disbanded the Order in 1312. The abrupt disappearance of a major part of the European infrastructure gave rise to speculation and legends, which have kept the "Templar" name alive into the modern day. Some modern Masonic organizations claim and affinity or descent from the Templars or have "degrees" named after the Templars.

For more information, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knights_Templar or

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freemasonry.

Hospitallers: The Knights Hospitaller, also known as the Order of Hospitallers or simply Hospitallers, and known at various points in their history as the Order of St John, Knights of Rhodes, and Knights of Malta, were a major Western Christian military order that originated during the Middle Ages.

The Order arose around the work of an Amalfitan hospital located at the Muristan site in Jerusalem, founded around 1023 to provide care for poor, sick or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land. After the Western Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade, the organization became a religious and military order under its own charter, and was charged with the care and defense of the Holy Land. Following the conquest of the Holy Land by Islamic forces, the Order operated from Rhodes, over which it was sovereign, and later from Malta where it administered a vassal state under the Spanish viceroy of Sicily.

The Order was weakened by Napoleon's capture of Malta in 1798 and became dispersed throughout Europe. It regained strength during the early 19th century as it repurposed itself towards humanitarian and religious causes. Its modern-day Roman Catholic continuation is headquartered in Rome (in an independent single-building extraterritorial entity called S.M.O.M. -- the Sovereign Military Order of Malta -- with allied Protestant orders headquartered in the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden.)

For more information, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knights_Hospitaller,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sovereign_Military_Order_of_Malta