Exarchs --

Byzantine East impinges on Medieval RomeClick on small images and links below to go to individual pictures for Unit 4

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0401HagiaSophia.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0400BlachernaiPalace500AD.jpg

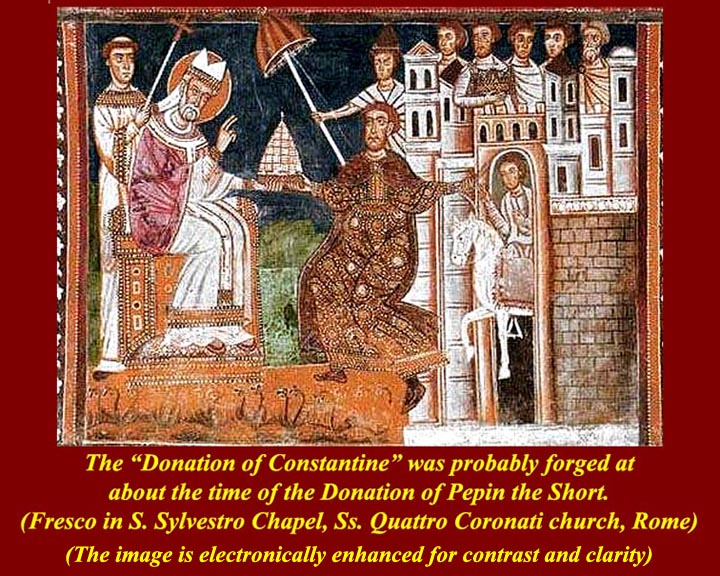

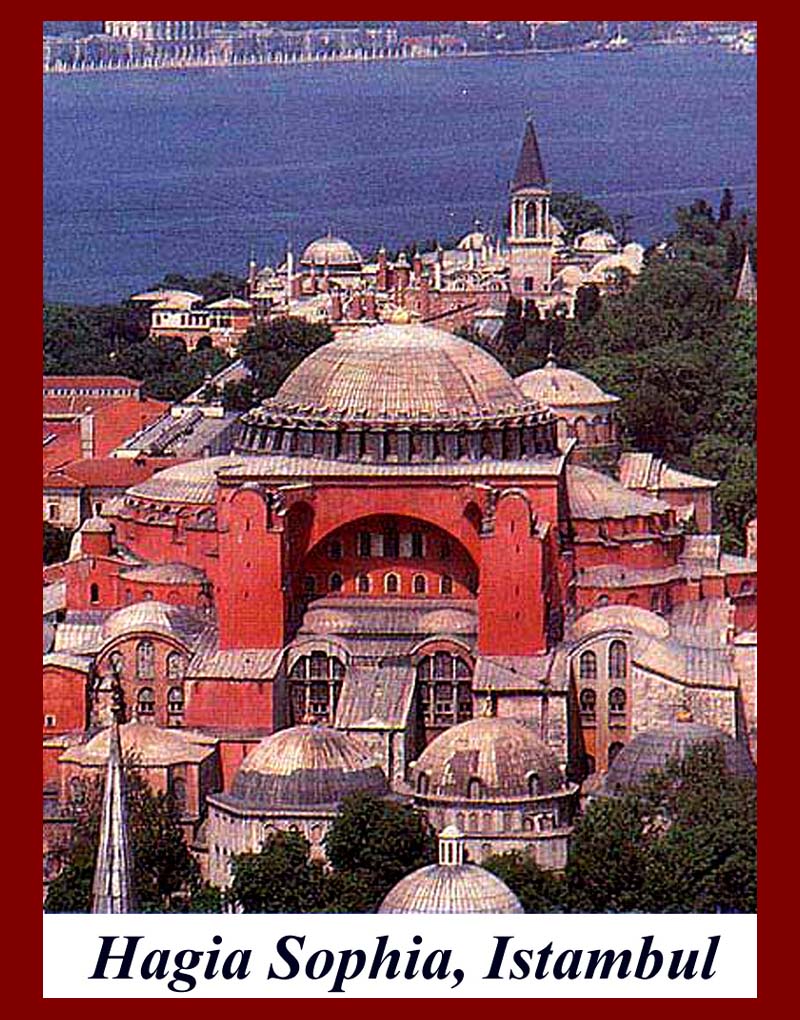

Hagia Sophia Church in Istanbul -- symbol of Eastern Christianity and last remnant of the Byzantine Great Palace of Constantinople. Hagia Sophia is a former Orthodox patriarchal basilica, later a mosque and now a museum in Istanbul, Turkey. From the date of its dedication in 360 until 1453, it served as the cathedral of Constantinople, except between 1204 and 1261, when it was the cathedral of the Latin Empire. The building was a mosque from 29 May 1453 until 1934, when it was secularized. It was opened as a museum on 1 February 1935.

Except for a few ruins, the Church is the only structure that survives of the huge complex of the Great Palace of Constantinople ((Greek: Μέγα Παλάτιον, Turkish: Büyük Saray) — also known as the Sacred Palace (Latin: Sacrum Palatium, Greek: Ιερόν Παλάτιον)). The palace complex was located in the south-eastern end of the peninsula now known as "Old Istanbul". It served as the main royal residence of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine emperors from 330 to 1081 and was the centre of imperial administration for over 800 years. Only a few remnants and fragments of its foundations have survived into the modern world.

[In the late 11th century, after the Exarchate period in the west, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118) moved his main residence to the Palace of Blachernae (Greek: τὸ ἐν Βλαχέρναις Παλάτιον), an imperial Byzantine residence in the suburb of Blachernae, located in the northwestern section of Constantinople (Istanbul), which had been built about 500 AD. The area of the palace is now mostly overbuilt. He and his grandson Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180) fortified the palace precinct.]

For information on the Great Palace, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Palace_of_Constantinople.

For information on the cathedral, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagia_Sophia.

For information on Sophia as a philosophical concept and on Sophia as the female principal (eventually abandoned) in the Christian Trinity, see http://www.crystalinks.com/sophia.html and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophia_(wisdom).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0402aaJulianApostate361-63.jpg

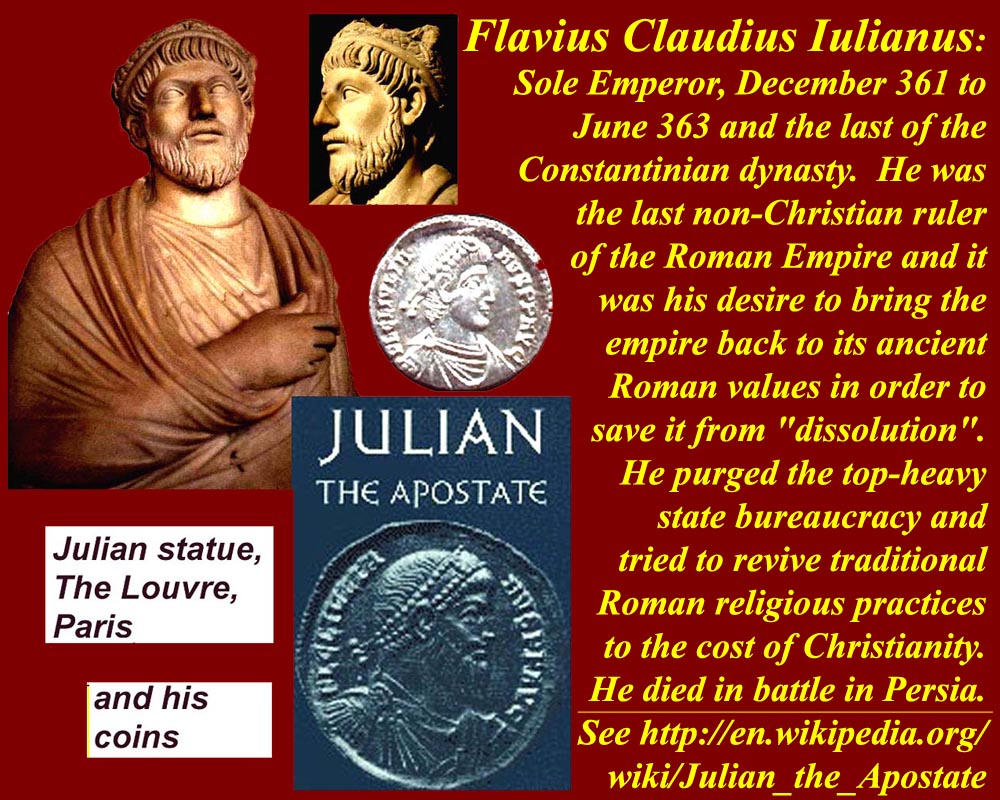

Julian the Apostate (333/332 - 363 AD). Flavius Claudius Julianus was Roman Emperor from 355 to 363. He is also a noted philosopher and Greek writer. The last member of the Constantinian dynasty, he was made Caesar by Constantius II in 355 and took command of the western provinces. During his reign he campaigned successfully against the Alamanni and Franks. Most notable was his crushing victory over the Alamanni in 357 at the Battle of Argentoratum (modern Strasgourg, Alsace, France) - despite being outnumbered. In 360 he was acclaimed Augustus by his soldiers, sparking a civil war between Julian and Constantius. But, Constantius died before the two could face each other in battle and named Julian as his rightful successor. In 363, Julian embarked on an ambitious campaign against the Sassanid Empire. Though initially successful, Julian was mortally wounded in battle and died shortly after.

Julian was a man of unusually complex character: he was a military commander, a philosopher, a social reformer, and a man of letters. He was the last non-Christian ruler of the Roman Empire and it was his desire to bring the empire back to its ancient Roman values in order to save it from dissolution. He purged the top-heavy state bureaucracy and attempted to revive traditional Roman religious practices at the cost of Christianity. His rejection of Christianity in favour of Neoplatonic paganism caused him to be called Julian the Apostate by the church.

Julian was raised as an Arian Christian, but apparently thought that Christianity and other outside Religions were disruptive to the empire and tried to suppress them.

Almost 400 thousand sites answer to Internet for information about Julian the Apostate. Here are five:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_the_Apostate,

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08558b.htm,

http://www.roman-emperors.org/julian.htm,

http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/julian/a/Julianapostate.htm, and

http://ancienthistory.about.com/library/bl/bl_text_gibbonxxiii_1.htm.

Arianism, which took its name from Arius (ca. AD 250–336), the leader of a Christian congregation in Alexandria disagreed with the the "trinitarian" Christan view (which eventually became standard) that the three persons of the Christian trinity were all equal. Arius held (and this is a very simplified explanation) that Jesus, as the son of the father, had to be subject to the father and therefore was somehow not as powerful as the father. The dispute between trinitarian and Arian Christianity lasted for centuries and was the cause of much intra-Christian bloodletting.

Many of the barbarian groups that passed through the Medieval Europe were nominally Arian Christians, but religious issues generally do not appear to have been important motivating factors for their movements.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0402abRavennaWImperial Capital.jpg

During the Medieval period, the capital of the Western Empire moved first to Milan and then to Ravenna, where it was through the Exarchate period. For information on Ravenna, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ravenna or http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12662b.htm or http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exarchate_of_Ravenna.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0403Theodosius379-95.jpg

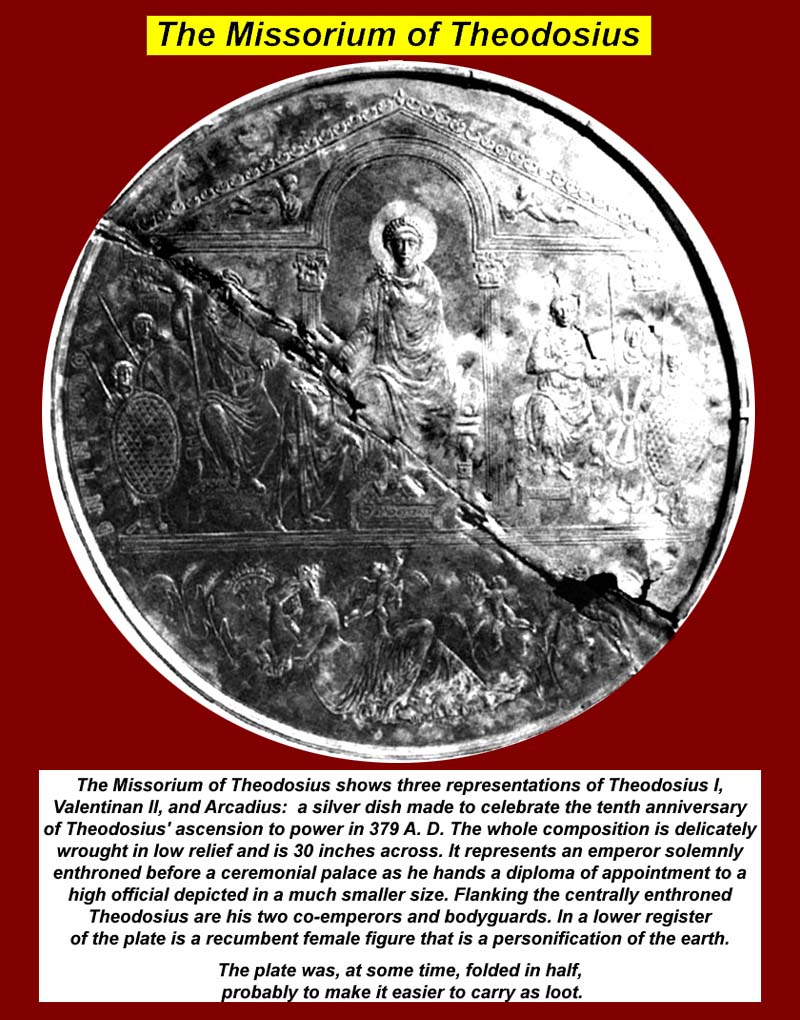

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0404MissoriumTheod.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0b/Theodosius-1-.jpg

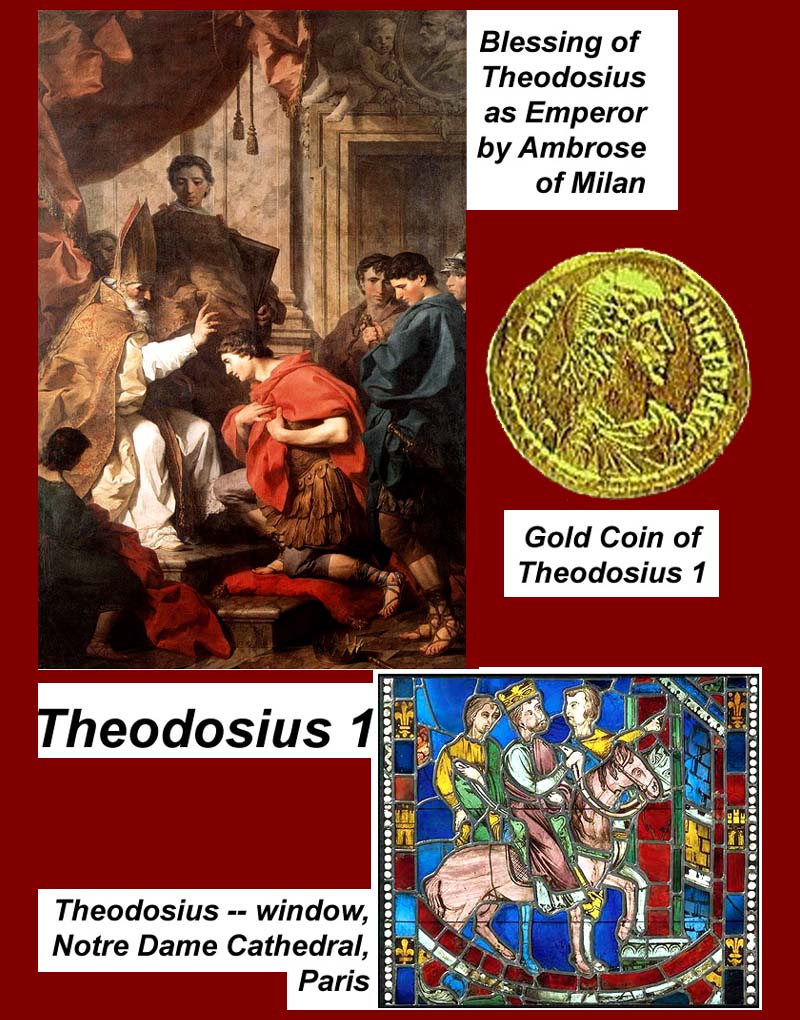

Flavius Theodosius (11 January 347 – 17 January 395), commonly known as Theodosius I or Theodosius the Great, was Roman Emperor from 379 to 395. He was the last emperor of the (united) Eastern and Western Roman Empire. During his reign, the Goths secured control of Illyricum after the Gothic War - establishing their homeland south of the Danube within the empire's borders. He is known for making Nicene Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire, issuing decrees that effectively worked towards melding the Roman state and the Christian Church into a single de facto church-state entity.

Although toleration was give to Christianity in 311CE by Constantine I, Christianity did not become the legal religion of the Roman Empire until the reign of Theodosius I (379-395). At that point not only was Christianity made the official religion of the Empire, but other religions were declared illegal.

Theodosian Code XVI.1.2

It is our desire that all the various nation which are subject to our clemency and moderation, should continue to the profession of that religion which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter, as it has been preserved by faithful tradition and which is now professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic holiness. According to the apostolic teaching and the doctrine of the Gospel, let us believe in the one deity of the father, Son and Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy Trinity. We authorize the followers of this law to assume the title Catholic Christians; but as for the others, since in out judgment they are foolish madmen, we decree that the shall be branded with the ignominious name of heretics, and shall not presume to give their conventicles the name of churches. They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of divine condemnation an the second the punishment of out authority, in accordance with the will of heaven shall decide to inflict.

-----------------------------------------------------------

from Henry Bettenson, ed., Documents of the Christian Church, (London: Oxford University Press, 1943), p. 31 [Short extract used under fair-use provisions]

This text is part of the Internet Medieval Source Book. The Sourcebook is a collection of public domain and copy-permitted texts related to medieval and Byzantine history and can be found on the Internet at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/sbook.html.

Theodosius was responsible for the destruction of some prominent pagan temples: the Serapeum in Alexandria, the temple of Apollo in Delphi, and that of the Vestal Virgins in Rome. After his death, Theodosius' sons Arcadius and Honorius inherited the East and West halves respectively, and the Roman Empire was never again re-united.

For more information on Theodosius, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodosius_I or

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14577d.htm or

http://www.roman-emperors.org/theo1.htm.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0405RomAugustulus475-76.jpg

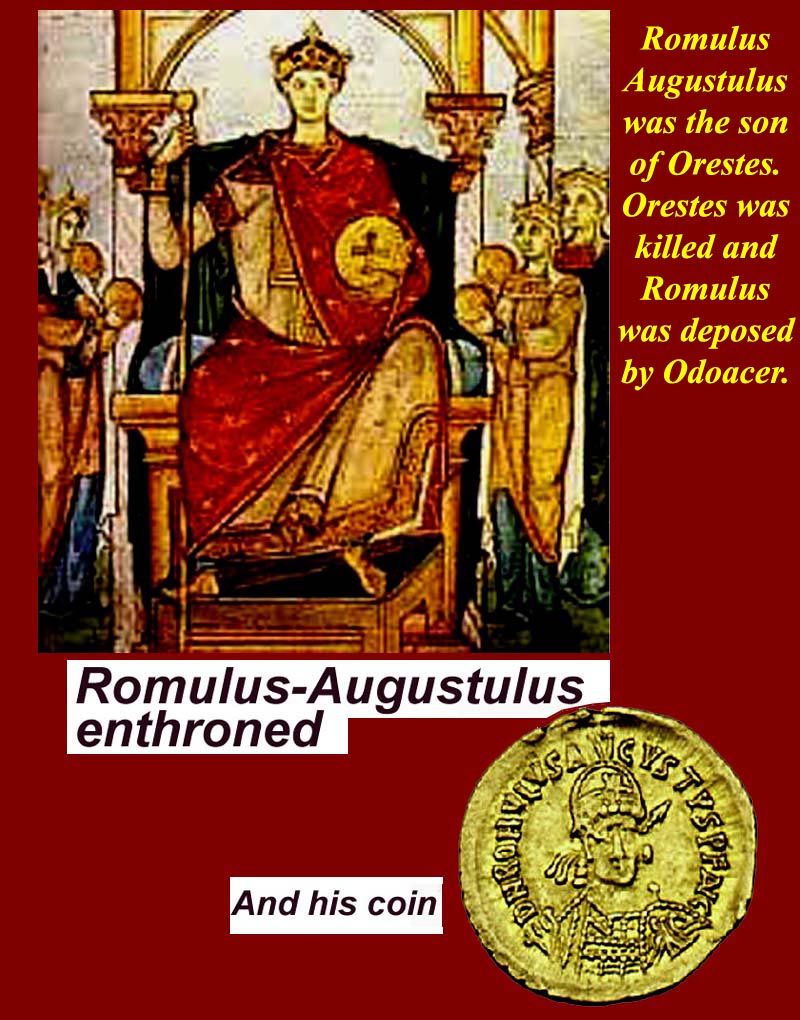

Romulus Augustus (fl. 461/463 – after 476, before 488), was the last Western Roman Emperor, reigning from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. His deposition by Odoacer is used to mark the end of the Western Roman Empire, the fall of ancient Rome, and the beginning of the Middle Ages in Western Europe.

The historical record contains few details of Romulus' life. He was installed as emperor by his father Orestes, the Magister militum (master of soldiers) of the Roman army, who had previously been an aide to Attila and who had arrived in Ravenna with a large force of former Attila fighters. Orestes quickly deposed the previous emperor Julius Nepos. Romulus, little more than a child, acted as a figurehead for his father's rule. Reigning for only ten months, Romulus was then deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer and sent to live in the Castellum Lucullanum in Campania; afterward he disappears from the historical record.

For more on Romulus Augustulus, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romulus_Augustulus or

http://www.roman-emperors.org/auggiero.htm or

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13179c.htm.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0405vJustinianRavenna.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0402wJustinianConque.jpg

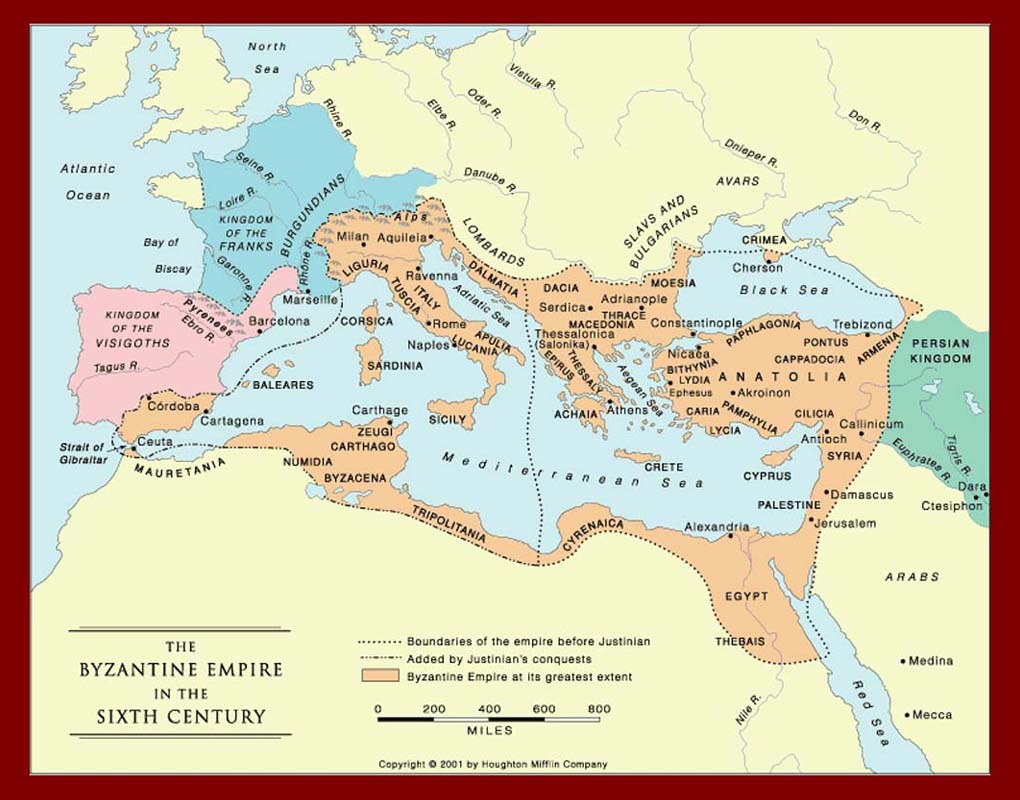

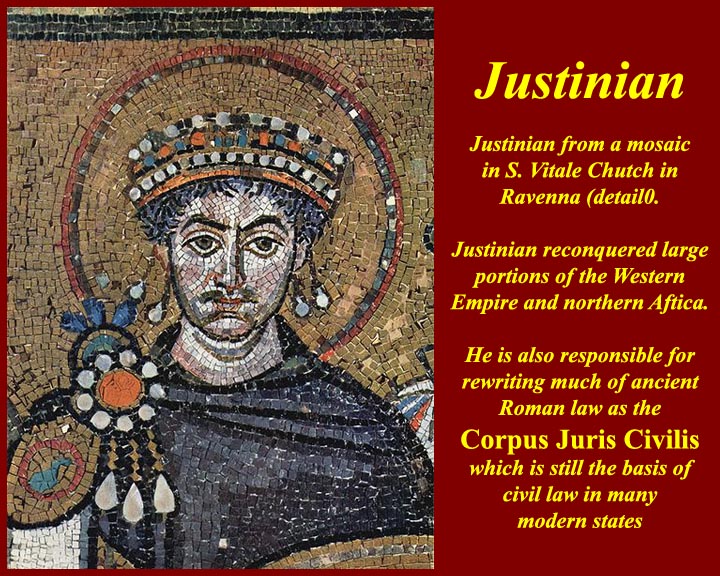

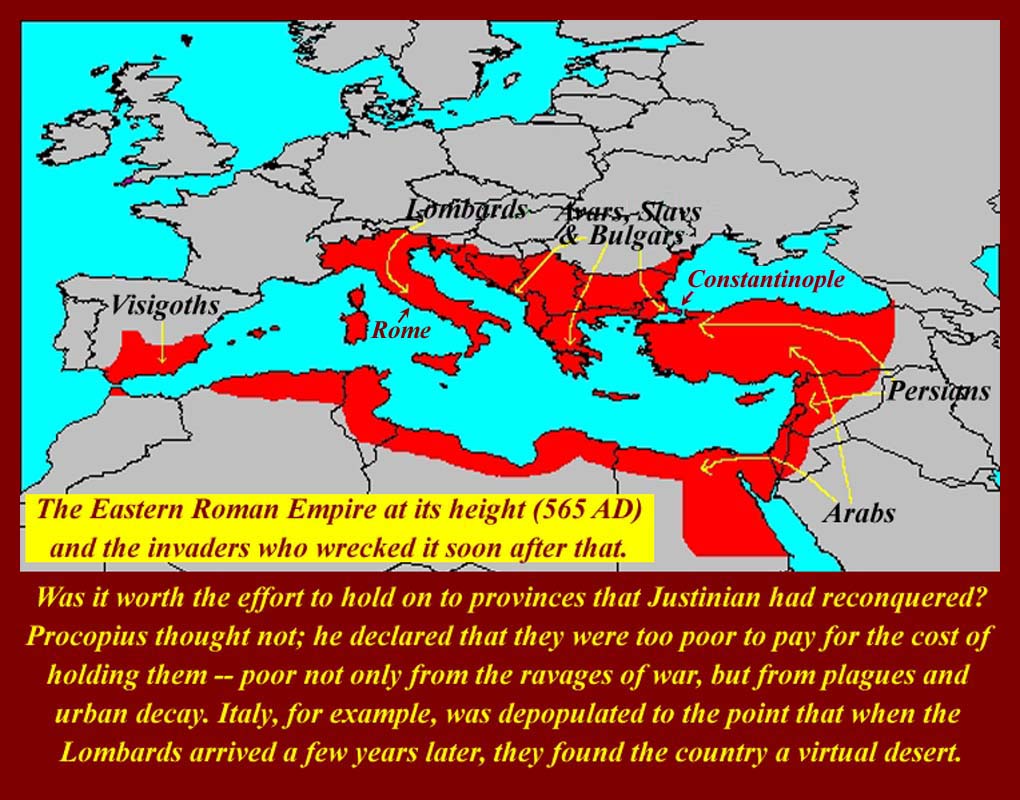

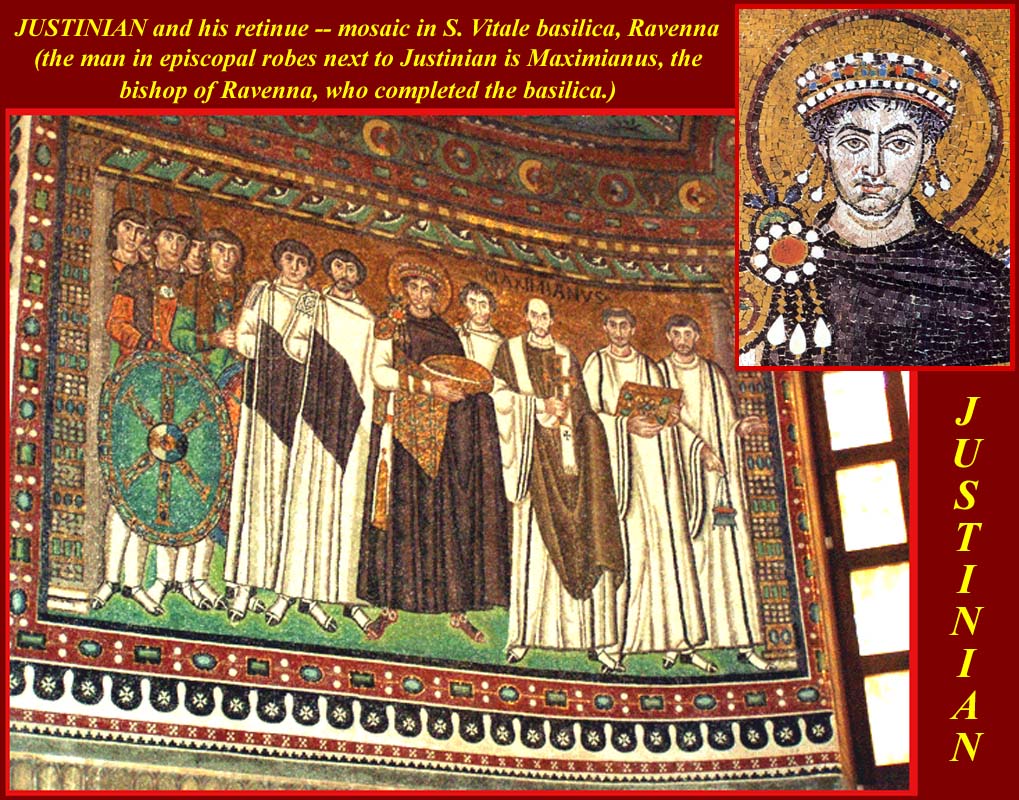

Justinian I (Latin: Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Justinianus; Greek: Φλάβιος Πέτρος Σαββάτιος Ἰουστινιανός; 483 – 13 or 14 November 565), commonly known as Justinian the Great, was Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, Justinian sought to revive the empire's greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the classical Roman Empire.

One of the most important figures of Late Antiquity and the last emperor to speak Latin as a first language, Justinian's rule constitutes a distinct epoch in the history of the Eastern Roman Empire. The impact of his administration extended far beyond the boundaries of his time and domain. Justinian's reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized renovatio imperii, or "restoration of the empire". This ambition was expressed in the partial recovery of the territories of the Western Roman Empire, including the city of Rome itself. A still more resonant aspect of his legacy was the uniform rewriting of Roman law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, which is still the basis of civil law in many modern states. His reign also marked a blossoming of Byzantine culture, and his building program yielded such masterpieces as the church of Hagia Sophia, which was to be the center of Eastern Orthodox Christianity for many centuries.

A devastating outbreak of bubonic plague (see Plague of Justinian) in the early 540s marked the end of an age of splendor. Thereafter. the empire entered a period of territorial decline not to be reversed until the ninth century.

For more on Justinian, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Justinian_I or

http://www.roman-emperors.org/justinia.htm or

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/just/hd_just.htm.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0405xBelisarius.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0405y-PostJustinian.jpg

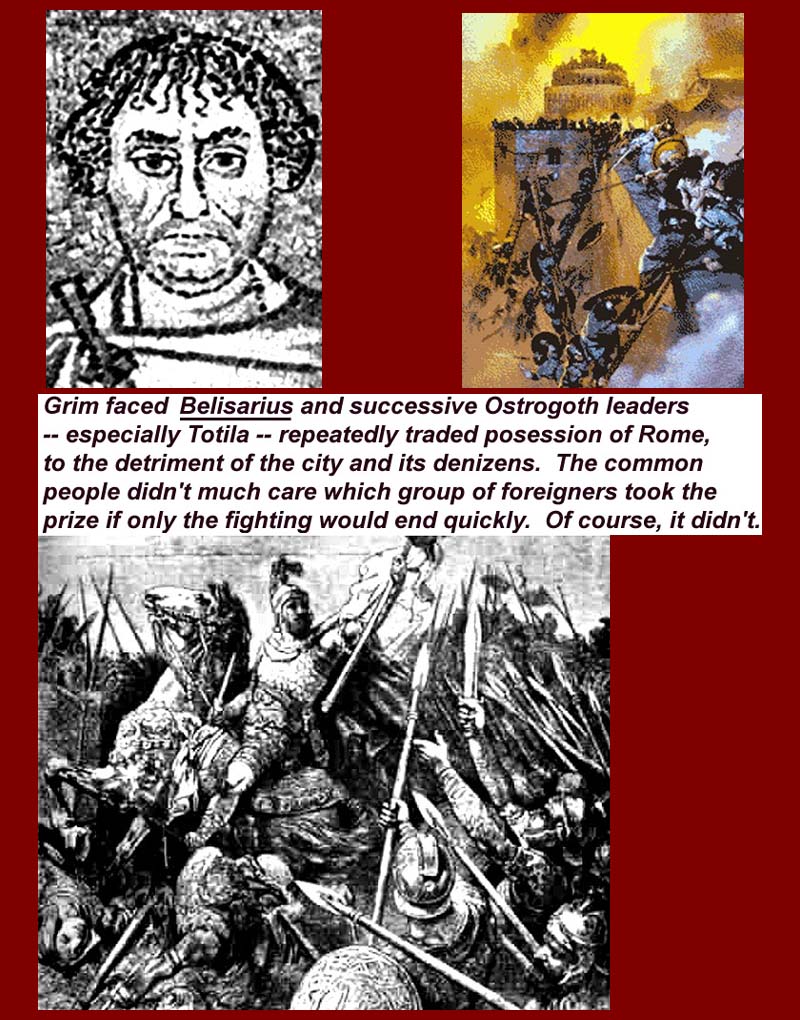

Flavius Belisarius (Greek: Βελισάριος, ca. AD 500 – AD 565) was one of the greatest generals of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. He was a major actor in Emperor Justinian's ambitious project of reconquering much of the Mediterranean territory of the former Western Roman Empire, which had been lost less than a century previously. On the Italian peninsula, his opponents were the Ostrogoths. Rome changed hands several times before the final defeat of the Ostrogoths by the successor of Belisarius, the eunuch general Narses. Each time Rome changed hands, there was more destruction in the city, whose inhabitants did not really care which side won. All the Romans wanted was peace, but it was long in coming; the war lasted from 535 to 554, and it's hard to say which side did the most damage to Rome.

One of the defining features of Belisarius' career was his success despite the little or no support he received from Justinian, who was jealous and fearful of Belisarius' power. Belisarius was recalled several times on the eves of victories and was finally replaced in Italy by Narses. Belisarius is considered by some to be the "last of the Romans".

Fittingly, Belisarius and Justinian, whose sometimes strained partnership increased the size of the empire by 45%, died within a few weeks of one another in November of 565. Belisarius owned a large estate of Rufinianae on the Asiatic side of the Constantinople suburbs. He may very well have died there and been buried near one of the two churches in the area, probably Saints Peter and Paul.

The Medieval legend that Justinian had Belesarius blinded and reduced to beggary is almost surely false, although it was a popular subject of art after the publication of Jean-François Marmontel's 1767 novel Bélisaire. Longfellow's 1875 poem Belisarius has him poor, old, blind, sunburned, and covered with the dust of Justinian's chariot wheels outside the city gate. Robert Graves' 1938 novel, Count Belisarius, is based on a biased and somewhat hostile account in the 6th century Secret History of Procopius, but the Graves' account is generous.

Shortly after the death of Justinian, his successors lost Italy once again. This was largely due to the mistaken foreign policies of Justinian rather than to their own shortcomings. While Justinian was pursuing his western campaigns he was also paying massive bribes to the Sassanid Persians to his east to keep them at bay. The bribes depleted the Byzantine treasury at the same time that they enriched the Persians. So when the Byzantines became too poor to support a large military establishment in the west or in the east, the rich Persians had meanwhile felt rich and strong enough to mount an attack. The Persians pushed in as far as the Bosporus. Heraclius II, Justinian's successor, ultimately was able to eject the Persians from the Eastern Empire and finally defeat them. But in the meantime, Italy and the west had to be abandoned -- they were simply too expensive and unproductive to keep.

the successor of Justinian

For more information on Belisarius, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belisarius or

http://www.biographybase.com/biography/Belisarius.html.

Longfellow's poem is at http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/belisarius/.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aaddExarchate650.jpg

The Exarchate (orange) and the Lombards (gray) in 652

Capital Ravenna

Historical era Early Middle Ages

- Lombard invasion of Italy 568

- Foundation of Exarchate 584

- Fall of Ravenna 751

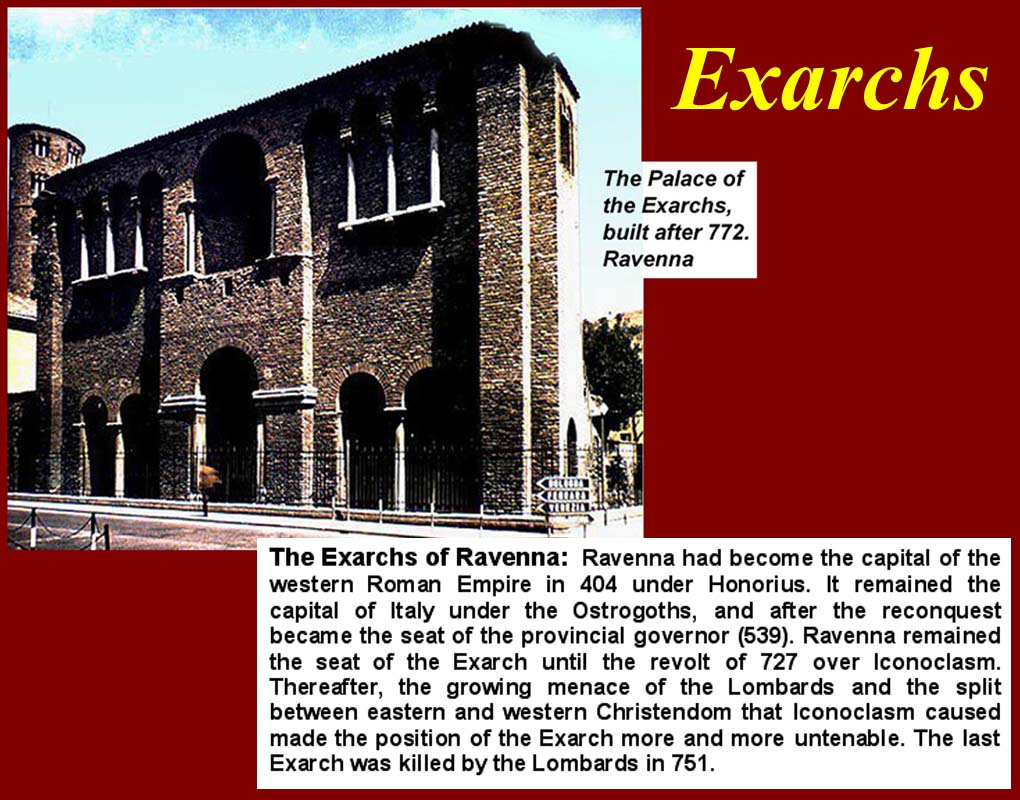

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0407ExarchPalace.jpg

(From Wikipedia -- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exarchate_of_Ravenna)

Exarchate of Ravenna (584 – 751)

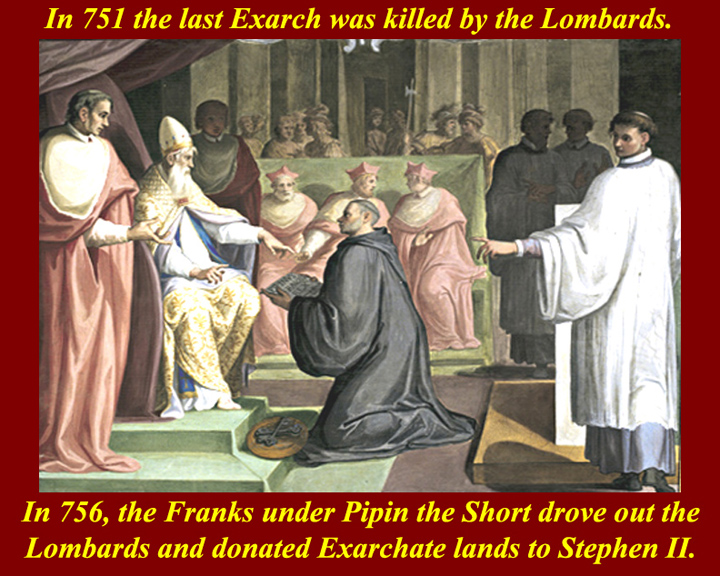

The Exarchate of Ravenna or of Italy was a centre of Byzantine power in Italy, from the end of the 6th century to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the Lombards.

Ravenna became the capital of the Western Roman Empire in 402 under Honorius, due to its fine harbour with access to the Adriatic and its ideal defensive location amidst impassable marshes. The city remained the capital of the Empire until its dissolution in 476, when it became the capital of Odoacer, and then of the Ostrogoths under Theodoric the Great. It remained the capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom, but in 540 during the Gothic War (535–554), Ravenna was occupied by the great Eastern Roman general Belisarius. After this reconquest it became the seat of the provincial governor. At that time, the administrative structure of Italy followed, with some modifications, the old system established by Emperor Diocletian, and retained by Odoacer and the Goths.

The Lombard invasion and Byzantine reaction: In 568, the Lombards under their king Alboin, together with other Germanic allies, invaded northern Italy. The area had only a few years ago been completely pacified, and had suffered greatly during the long Gothic War. The local Roman forces were weak, and after taking several towns, in 569 the Lombards conquered Milan. They took Pavia after a three-year siege in 572, and made it their capital.[1] In subsequent years, they took Tuscany. Others, under Faroald and Zotto, penetrated into central and southern Italy, where they established the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento. [2] However, after Alboin's murder in 573, the Lombards fragmented into several autonomous duchies (the "Rule of the Dukes").

Emperor Justin II tried to take advantage of this, and in 576 he sent his son-in-law, Baduarius, to Italy. However, he was defeated and killed in battle, [3] and the continuing crises in the Balkans and the East meant that another imperial effort at reconquest was not possible. Because of the Lombard incursions, the Roman possessions had fragmented into several isolated territories, and in 580, Emperor Tiberius II reorganized them into five provinces, now termed in Greek, eparchies: the Annonaria in northern Italy around Ravenna, Calabria, Campania, Emilia and Liguria, and the Urbicaria around the city of Rome (Urbs). Thus by the end of the sixth century the new order of powers had settled into a stable pattern. Ravenna, governed by its exarch, who held civil and military authority in addition to his ecclesiastical office, was confined to the city, its port and environs as far north as the Po, beyond which lay territory of the duke of Venice, nominally in imperial service, and south to the Marecchia River, beyond which lay the Pentapolis on the Adriatic, also under a duke nominally representing the Emperor of the East. [4]

The Exarchate: The exarchate was organized into a group of duchies (i.e the Duchy of Rome, Duchy of Venetia, Duchy of Calabria, Lucania, Spoleto etc) which were mainly the coastal cities in the Italian peninsula since the Lombards held the advantage in the hinterland.

The civil and military head of these imperial possessions, the exarch himself, was the representative at Ravenna of the emperor in Constantinople. The surrounding territory reached from the boundary with Venice in the north to the Pentapolis at Rimini, the border of the "five cities" in the Marches along the Adriatic coast; and reached even cities not on the coast, as Forlì for instance. All this territory lies on the eastern flank of the Apennines; this was under the exarch's direct administration and formed the Exarchate in the strictest sense. Surrounding territories were governed by dukes and magistri militium more or less subject to his authority. From the perspective of Constantinople, the Exarchate consisted of the province of Italy.

The Exarchate of Ravenna was not the sole Byzantine province in Italy. Byzantine Sicily formed a separate government, and Corsica and Sardinia, while they remained Byzantine, belonged to the Exarchate of Africa.

The Lombards had their capital at Pavia and controlled the great valley of the Po. The Lombard wedge in Italy spread to the south, and established duchies at Spoleto and Beneventum; they controlled the interior, while Byzantine governors more or less controlled the coasts.

The Piedmont, Lombardy, the interior mainland of Venetia, Tuscany and the interior of Naples belonged to the Lombards, and bit by bit the Imperial representative in Italy lost all genuine power, though in name he controlled areas like Liguria (completely lost in 640 to the Lombards), or Naples and Calabria (being overrun by the Lombard duchy of Benevento). In Rome, the pope was the real master.

At the end, ca 740, the Exarchate consisted of Istria, Venetia (except for the lagoon of Venice itself, which was becoming an independent protected city-state, the forerunner of the future republic of Venice), Ferrara, Ravenna (the exarchate in the limited sense), with the Pentapolis, and Perugia.

These fragments of the province of Italy, as it was when reconquered for Justinian, were almost all lost, either to the Lombards, who finally conquered Ravenna itself about 750, or by the revolt of the pope, who finally separated from the Empire on the issue of the iconoclastic reforms.

The relationship between the Pope in Rome and the Exarch in Ravenna was a dynamic that could hurt or help the empire. The Papacy could be a vehicle for local discontent. The old Roman senatorial aristocracy resented being governed by an Exarch who was considered by many a meddlesome foreigner. Thus the exarch faced threats from without as well as from within, hampering much real progress and development.

In its internal history the exarchate was subject to the splintering influences which were leading to the subdivision of sovereignty and the establishment of feudalism throughout Europe. Step by step, and in spite of the efforts of the emperors at Constantinople, the great imperial officials became local landowners, the lesser owners of land were increasingly kinsmen or at least associates of these officials, and new allegiances intruded on the sphere of imperial administration. Meanwhile the necessity for providing for the defense of the imperial territories against the Lombards led to the formation of local militias, who at first were attached to the imperial regiments, but gradually became independent, as they were recruited entirely locally. These armed men formed the exercitus romanae militiae, who were the forerunners of the free armed burghers of the Italian cities of the Middle Ages. Other cities of the exarchate were organized on the same model.

The end of the Exarchate: During the 6th and 7th centuries the growing menace of the Lombards and the Franks, and the split between eastern and western Christendom caused by Iconoclasm and the acrimonious rivalry between the Pope and the patriarch of Constantinople, made the position of the exarch more and more untenable.

Ravenna remained the seat of the exarch until the revolt of 727 over Iconoclasm. Eutychius, the last exarch of Ravenna, was killed by the Lombards in 751. The exarchate was reorganized as the Catapanate of Italy headquartered in Bari which was lost to the Saracens in 847 and only recovered in 871.

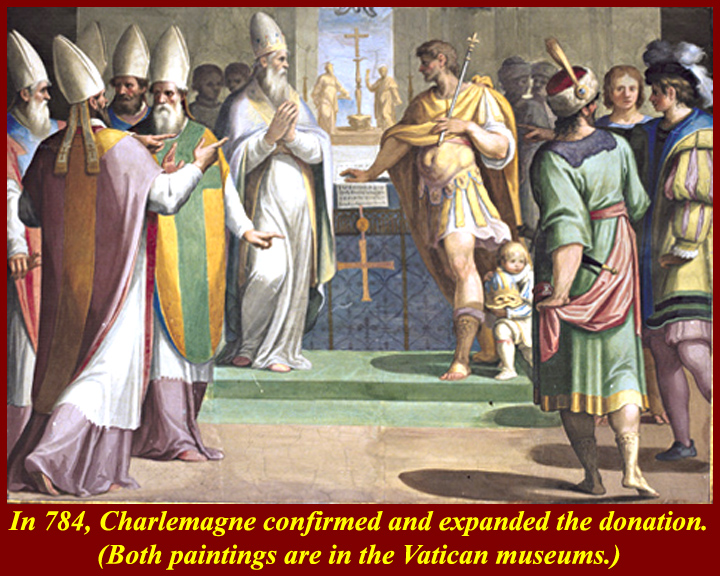

When in 756 the Franks drove the Lombards out, Pope Stephen II claimed the exarchate. His ally Pippin the Younger, King of the Franks, donated the conquered lands of the former exarchate to the Papacy in 756; this donation, which was confirmed by his son Charlemagne in 774, marked the beginning of the temporal power of the popes as the Patrimony of Saint Peter. The archbishoprics within the former exarchate, however, had developed traditions of local secular power and independence, which contributed to the fragmenting localization of powers. Three centuries later, that independence would fuel the rise of the independent communes.

So the Exarchate disappeared, and the small remnants of the imperial possessions on the mainland, Naples and Calabria, passed under the authority of the Catapan of Italy, and when Sicily was conquered by the Arabs in the 9th century the remnants were erected into the themes of Calabria and Langobardia. Istria at the head of the Adriatic was attached to Dalmatia.

Exarchs of Ravenna: (Note: For some exarchs there exists some uncertainty over their exact tenure dates.)

Decius (584-585)

Smaragdus (585-589) died 611

Romanus (589-598)

Callinicus (598-603)

Smaragdus (restored) (603-611)

John I Lemigius (611-615)

Eleutherius (616-619) died 620

Isaac ( 625-643)

Theodore I Calliopas ( 643-c. 645)

Plato (c. 645-649)

Olympius (649-652)

Theodore I Calliopas (restored) (653-before 666)

Gregory (c. 666-678)

Theodore II (678-687)

John II Platinus (687-702)

Theophylactus (702-710)

John III Rizocopo (710-711)

Entichius (711-713)

Scholasticus (713-726)

Paul (726-727)

Eutychius (728-752)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aaeIconoclasm7-800s.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aafIconoclasmIdeal.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aagIconoclasm1560LaRochelle2.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aahNijmegenNetherlandsStevenskerk1566.JPG

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aajDestruction_of_Buddhas_March_21_2001.jpg

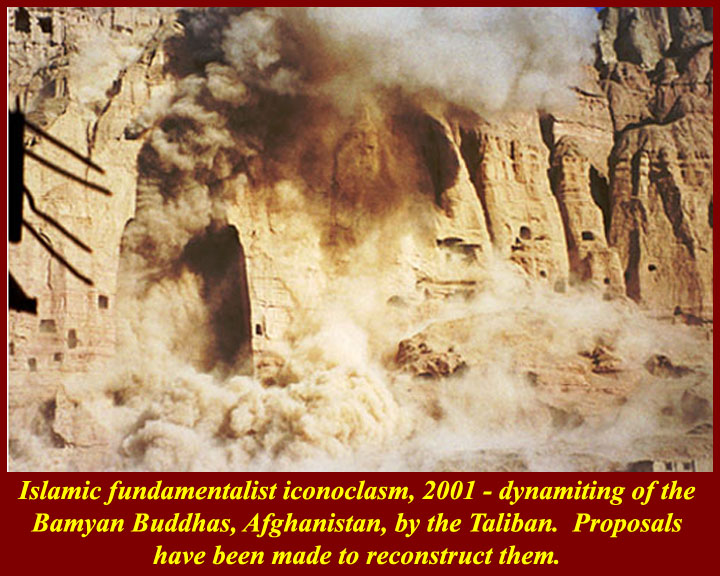

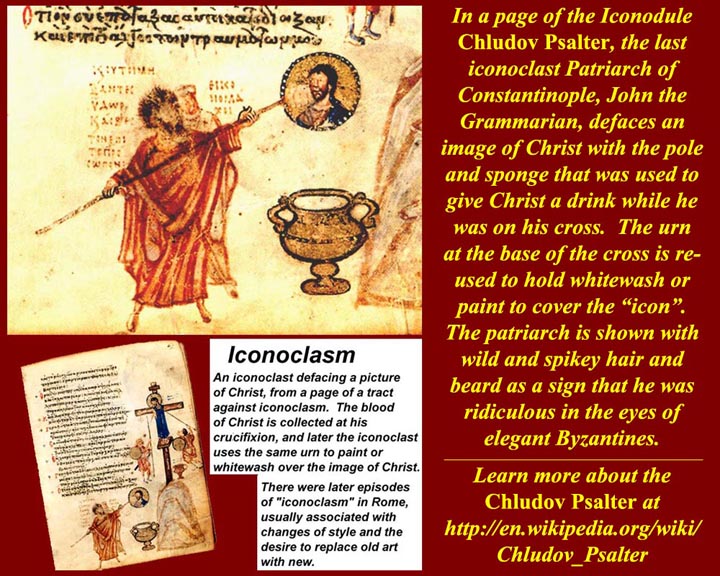

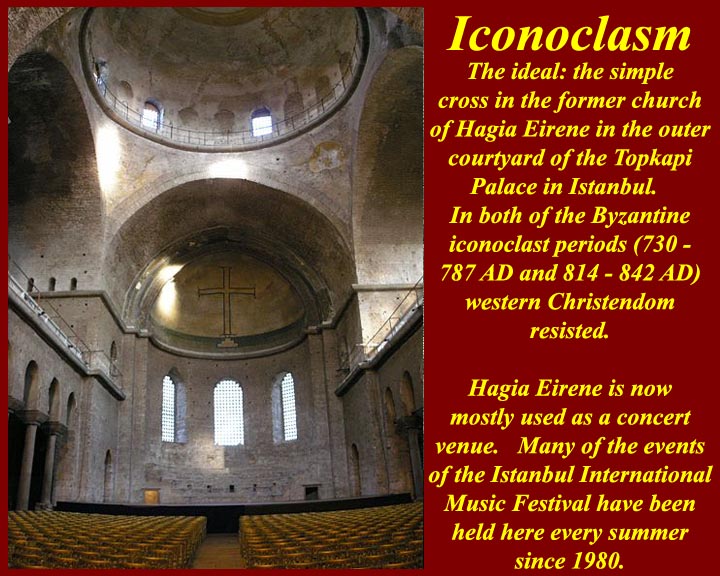

One of the main contributing factors to the end of the Exarchate was the question of iconoclasm. In the Eastern Empire there were two periods of iconoclasm with which religious and civic officials and the people in the West resisted.

The Byzantine Iconoclasm (Greek: Εἰκονομαχία, Eikonomachía) refers to two periods in the history of the Byzantine Empire when Emperors, backed by imperially-appointed leaders and councils of the Greek Orthodox Church (which at the time was still united with the Roman Catholic Church as the State church of the Roman Empire) imposed a ban on religious images or icons. The "First Iconoclasm", as it is sometimes called, lasted between about 730 and 787, when a change on the throne reversed the ban. The "Second Iconoclasm" was between 814 and 842. Iconoclasm, Greek for "image-breaking", is the deliberate destruction within a culture of the culture's own religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually for religious or political motives. People who engage in or support iconoclasm are called iconoclasts, a term that has come to be applied figuratively to any person who breaks or disdains established dogmata or conventions. Conversely, people who revere or venerate religious images are derisively called "iconolaters" (εἰκονολάτραι). They are normally known as "iconodules" (εἰκονόδουλοι), or "iconophiles" (εἰκονόφιλοι).

Iconoclasm may be carried out by people of a different religion, but is often the result of sectarian disputes between factions of the same religion. In Christianity, iconoclasm has generally been motivated by an "Old-Covenant" interpretation of the Ten Commandments, which forbid the making and worshipping of "graven images", see also Biblical law in Christianity. The two serious outbreaks of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire during the 8th and 9th centuries were unusual in that the use of images was the main issue in the dispute, rather than a by-product of wider concerns. Religious and civic officials in the West refused to cooperate.

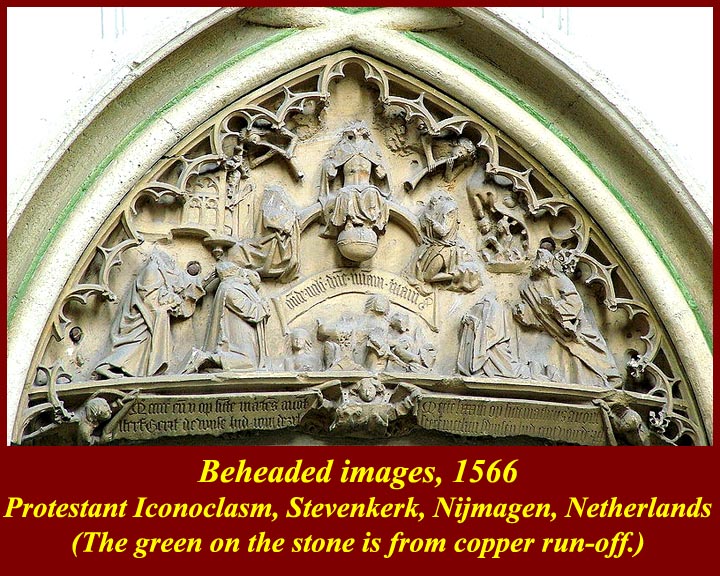

Iconoclasm did not end with the Byzantines. During the Reformation in Europe a similar phenomenon took hold, and as recently as 2001 Islamic fundamentalists destoyed the ancient Buddhas at Bamyan in Afghanistan.

Major periods of iconoclasm:

In the Roman Empire, pagan images were destroyed during the process of Christianisation.

In the world of Islam, there have been various periods of iconclasm against images of other religions and those produced within Islam itself.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Byzantine two periods of destruction of its own religious imagery.

In Europe during the Reformation and the religious conflicts following there were several outbreaks, with Protestants destroying Catholic or sometimes Protestant imagery.

During the French Revolution, there was destruction of religious and secular imagery.

During and after the Russian Revolution, there was widespread destruction of religious and secular imagery.

During and after the Communist takeover of China, especially in the Cultural Revolution there was widespread destruction of religious and secular imagery in China and Tibet.

For more information on iconoclasm, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Iconoclasm or

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iconoclasm or

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07620a.htm or

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/icon/hd_icon.htm.

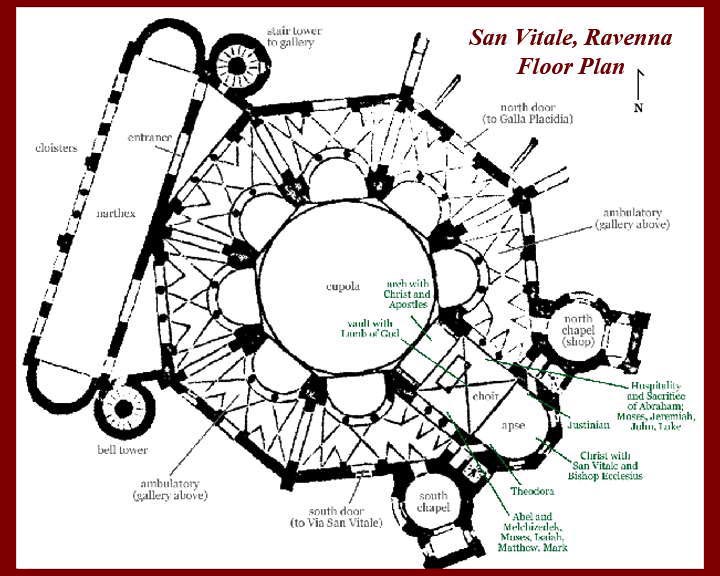

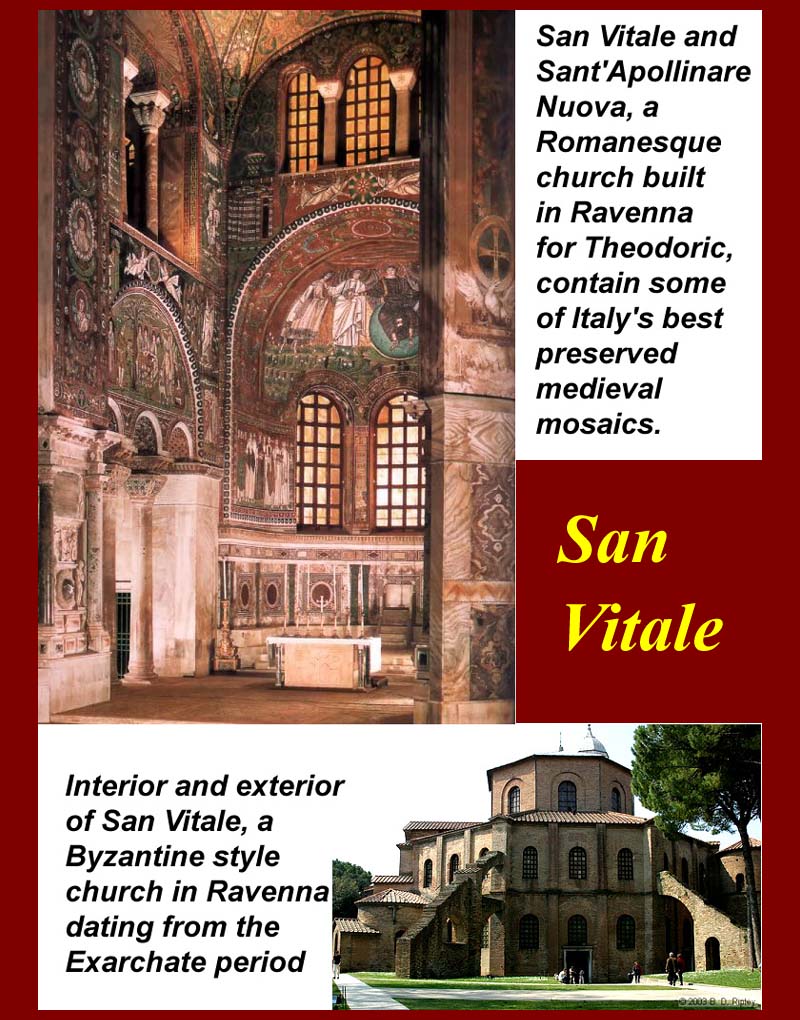

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aaSVitalleRavennaExt.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406abSVitalePlan.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406aSVitaleJustinian.jpg

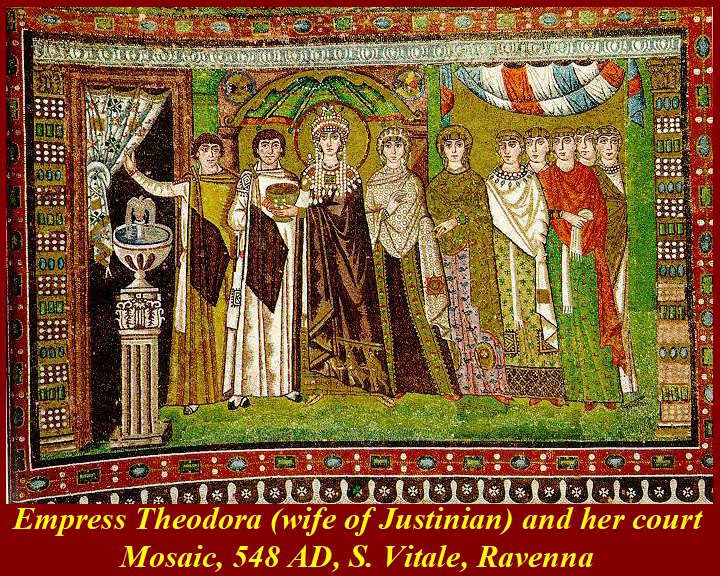

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406axSVitaleTheodora.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406ayRavennaSVitale.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0406azRavennaTombGalla.jpg

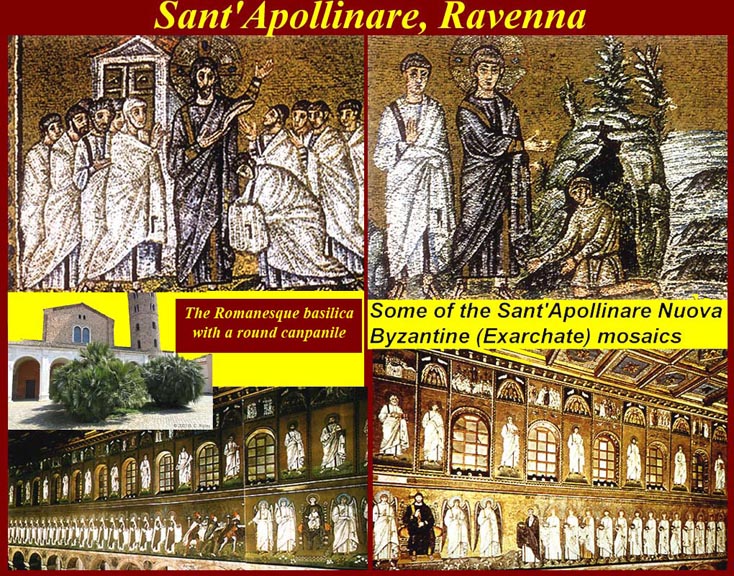

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0409ApollinareMosaics.jpg

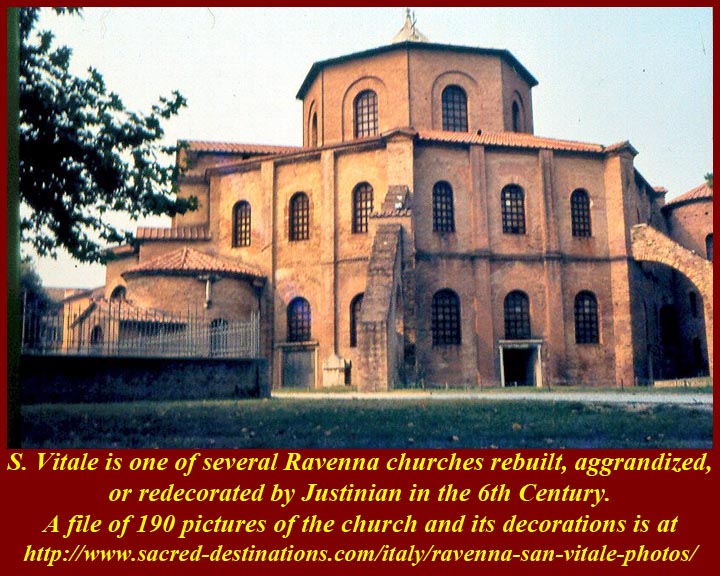

Two reason that Western Christians so vehemently opposed iconoclasm were (1) the long tradition of artistic imagery associated with both ancient Rome and with early Roman Christianty and (2) their possession of the great mosaic cycles in S. Vitale and S. Apollinaire in Ravenna. Western Christians flatly refused to destroy any of those artistic masterpieces. The two iconoclasm periods (730-787 and 814-842) in the East did not last long enough to cause the definitive split between the Eastern and Western churches, but they did soften the glue that held the whole structure together. The final split, the "great Schism" would wait until 1054 and would be caused by small doctrinal differences and large doses of bad attitude by Western and Eastern prelates.

Some of Ravenna's best mosaics are in S. Vitale Church and in the adjacent tomb of Galla Placidia (the lady with all those emperors in her family -- father, brothers, husband, son) and at S. Apollinaire church, all ow which are in Ravenna. There were also great Medieval mosaics in Rome and other cities, more of which we will see in Unit 9 of this course -- http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRomUnit0900-0PixList.html.

More images of the S. Vitale mosaics are at http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth212/san_vitale.html and at numerous other Internet sites. Description of the church are at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_San_Vitale and http://www.sacred-destinations.com/italy/ravenna-san-vitale.

More images of S. Apollinaire and a description of the church http://www.sacred-destinations.com/italy/ravenna-st-apollinare-nuovo.

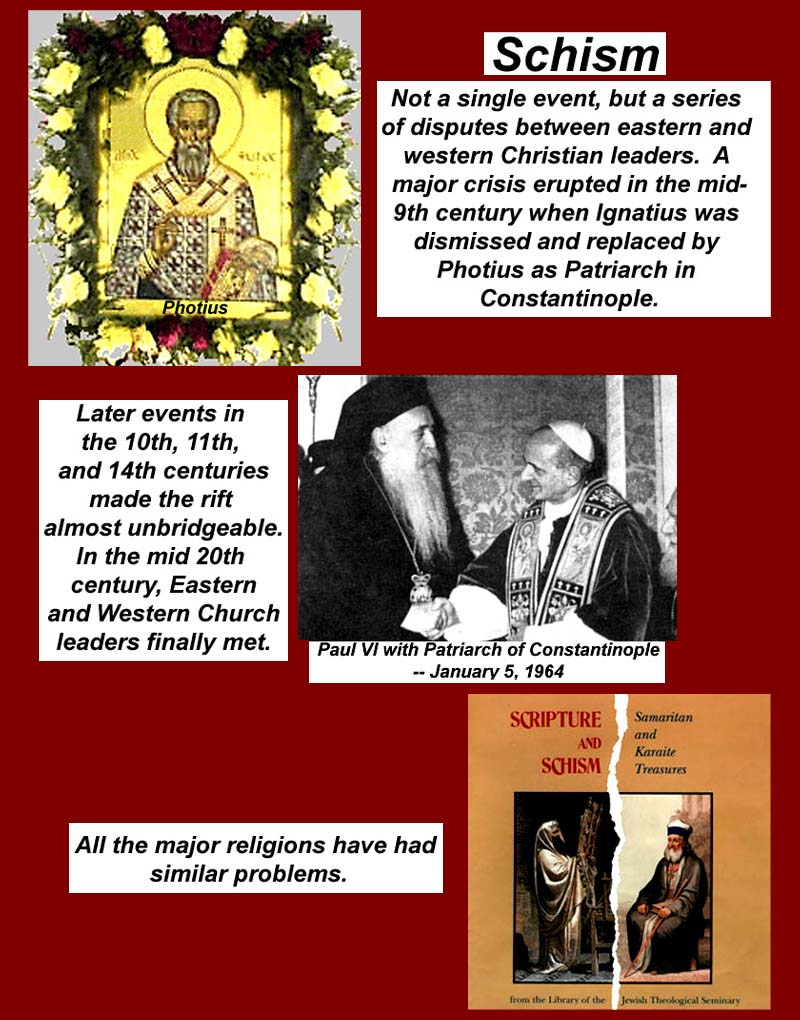

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0411Schism.jpg

Schism, from Old French cisme or scisme < Ancient Greek σχίσμα (skhisma, “division”) < σχίζω (skhizō, “I split” -- think of the psychological designation "schizophrenia"). A schism is a split or division between people, usually belonging to an organization or movement. The word is most frequently applied to a break of communion between two sections of Christianity that were previously a single body, or to a division within some other religion. It is also used of a split within a non-religious organization or movement or, more broadly, of a separation between two or more people, be it brothers, friends, lovers, etc.

A schismatic is a person who creates or incites schism in an organization or who is a member of a splinter group. Schismatic as an adjective means pertaining to a schism or schisms, or to those ideas, policies, etc. that are thought to lead towards or promote schism. In religion, the charge of schism is distinguished from that of heresy, since the offense of schism concerns not differences of belief or doctrine but promotion of, or the state of, division.

The "Great Schism" or the "East-West Schism" in Christianity, i.e., the split between the Catholic and Orthodox forms of Christianity, had many causes and took many years to come to come to a head. The final dispute, according to many authorities, was over a single phrase, "and the son", which the Western Church wanted to add to the Nicene Creed -- "filioque" in Latin. Actually, it was over the question of whether the westerners could amend the Creed with a council which they dominated. The principal of amendments to the Creed at councils that both sides accepted had already been established. The question, of course, was always, who's going to be in charge? In the event, the Western faction sent a "negotiator", but the talks quickly broke down with each side declaring that the other was excommunicated. Who shouted the first excommunication depends on which side is telling the story. The Church split along doctrinal, theological, linguistic, political, and geographical lines, and the fundamental breach has never been healed, with each side accusing the other of having fallen into heresy and of having initiated the division.

As is shown in the image, schism is not limited to Christianity.

One of the most fraught questions about "schism" is how to pronounce the word. The answer is that you avoid a schism by pronouncing it the way your interlocutor wants you to.

It's worth noting that, by the time the Great Schism took place, it was a purely ecclesiastical dispute. The Byzantines had irrevocably lost their military power and political influence in the west before 800 AD with the arrival first of the Lombards, who, led by their King, Aistulf, conquered Ravenna in 773, and the of the Franks, who, led by Pepin the Short (Charlemagne's father) expelled the Lombards from Ravenna in 776.

For information on schism, including links to some of the big ones, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schism. For information on the East-West or "Great" Schism, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East–West_Schism.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0412DonationPipin.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0413DonationCharlemagne.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0414DonationConstantine.jpg

The "Donation of Pepin", the first in 754, and second in 756, provided a legal basis for the formal organizing of the Papal States, which inaugurated papal temporal rule over civil authorities. The Donations were bestowed by Pepin the Short only three years after he became the first civil ruler appointed by a Pope, about the year 751. A few years later, Charlemagne expanded his father's donation in return for recognition as legitimate king of the Franks (and a papal coronation in 800 AD).

The Donation of Constantine (Latin, Donatio Constantini) is a forged Roman imperial decree by which the emperor Constantine I supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the pope. Scholars have dated the forgery between the Eighth and the Ninth Century. The earliest possible allusion to the Donatio is in a letter in which Pope Hadrian I exhorts Charlemagne to follow Constantine's example and endow the Roman church. It was clearly a defense of papal interests, perhaps against the claims of either the Byzantine Empire or those of Charlemagne himself, who soon assumed the former imperial dignity in the West and with it the title "Emperor of the Romans".

For information on the Carolingian and Constantinian Donations, see

http://www.traditioninaction.org/History/A_015_DonationCharlemagne.htm and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donation_of_Constantine.

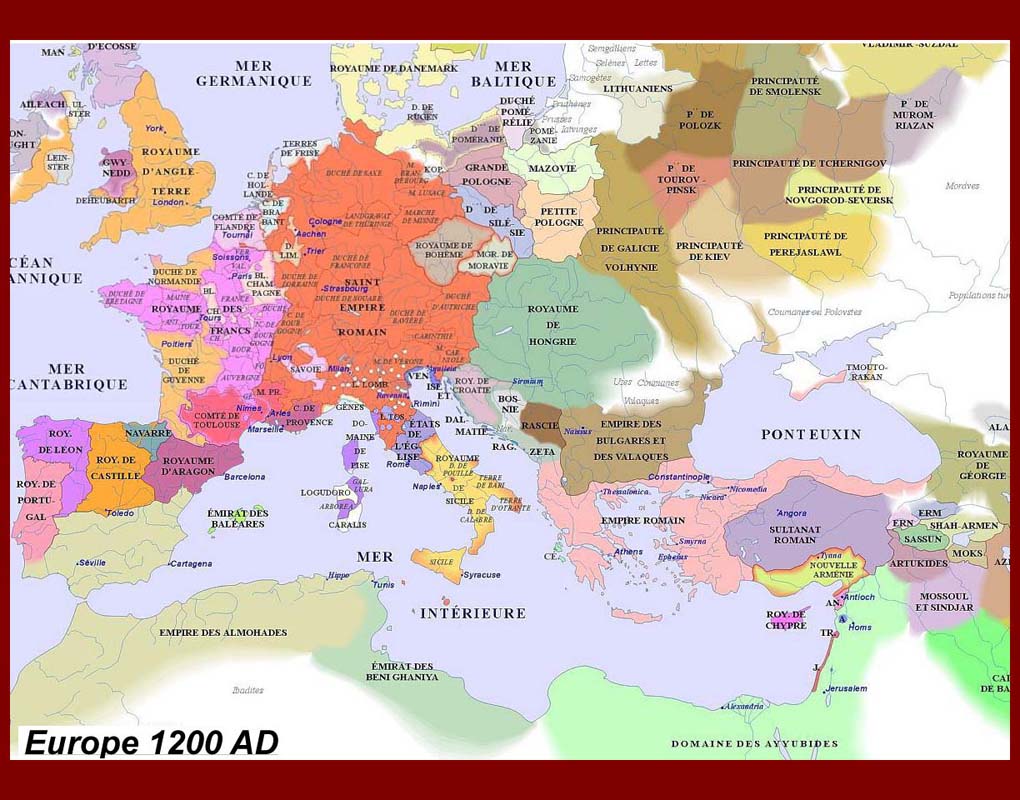

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0415-EmpireMap1200AD.jpg

The Byzantine Empire on the eve of the Fourth Crusade

Closing a loop: What finally happened to the Byzantines?

The fall of the Eastern Empire.

The 4th Crusade

In 1198, Pope Innocent III broached the subject of a new crusade through legates and encyclical letters. The stated intent of the crusade was to conquer Egypt, now the centre of Muslim power in the Levant. The crusader army that arrived at Venice in the summer of 1202 was somewhat smaller than had been anticipated, and there were not sufficient funds to pay the Venetians, whose fleet was hired by the crusaders to take them to Egypt. Venetian policy under the aging and blind but still ambitious Doge Enrico Dandolo was potentially at variance with that of the Pope and the crusaders, because Venice had close commercial relation with Egypt. The crusaders accepted the suggestion that in lieu of payment they assist the Venetians in the capture of the (Christian) port of Zara in Dalmatia (a vassal city of Venice, which had rebelled and placed itself under Hungary's protection in 1186). Zara fell in November 1202 after a brief siege. Innocent was informed of the plan, but his veto was disregarded. After the fact, Innocent was reluctant to jeopardize the Crusade and gave conditional absolution to the crusaders—not, however, to the Venetians.

After the death of Theobald III, Count of Champagne, the leadership of the Crusade passed to Boniface of Montferrat, a friend of the Hohenstaufen Philip of Swabia. Both Boniface and Philip had married into the Byzantine imperial family. In fact, Philip's brother-in-law, Alexios Angelos, son of the deposed and blinded emperor Isaac II Angelos, had appeared in Europe seeking aid and had made contacts with the crusaders. Alexios offered to reunite the Byzantine church with Rome, pay the crusaders 200,000 silver marks, and join the crusade with 200,000 silver marks and all the supplies they needed to get to Egypt. Innocent was aware of a plan to divert the Crusade to Constantinople and forbade any attack on the city, but the papal letter arrived after the fleets had left Zara.

The crusaders arrived at Constantinople in the summer of 1203, Alexios III fled from the capital, and Alexios Angelos was elevated to the throne as Alexios IV along with his blind father Isaac. However, Alexios IV and Isaac II were unable to keep their promises and were deposed by Alexios V. Eventually, the crusaders took the city on 13 April 1204. Constantinople was subjected by the rank and file to pillage and massacre for three days. Many priceless icons, relics, and other objects later turned up in Western Europe, a large number in Venice. According to the Byzantine historian Choniates, a prostitute was even set up on the Patriarchal throne. When Innocent III heard of the conduct of his crusaders, he castigated them in no uncertain terms. But the situation was beyond his control, especially after his legate, on his own initiative, had absolved the crusaders from their vow to proceed to the Holy Land -- an absolution, authorized or not, is valid. When order had been restored, the crusaders and the Venetians proceeded to implement their agreement; Baldwin of Flanders was elected emperor and the Venetian Thomas Morosini chosen patriarch. The lands parceled out among the leaders did not include all the former Byzantine possessions. The Byzantine rule continued in Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus.

Empire in exile

After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Latin Crusaders, two Byzantine successor states were established: the Empire of Nicaea, and the Despotate of Epirus. A third one, the Empire of Trebizond was created a few weeks before the sack of Constantinople by Alexios I of Trebizond. Of these three successor states, Epirus and Nicaea stood the best chance of reclaiming Constantinople. The Nicaean Empire struggled, however, to survive the next few decades, and by the mid-thirteenth century it lost much of southern Anatolia. The weakening of the Sultanate of Rûm following the Mongol Invasion in 1242–43 allowed many Beyliks and ghazis to set up their own principalities in Anatolia, weakening the Byzantine hold on Asia Minor. In time, one of the Beys, Osman I, created an empire that would conquer Byzantium. However, the Mongol Invasion also gave Nicaea a temporary respite from Seljuk attacks allowing it to concentrate on the Latin Empire only north of its position.

Reconquest of Constantinople: The Byzantine Empire c. 1263

The Empire of Nicaea, founded by the Laskarid dynasty, managed to reclaim Constantinople from the Latins in 1261 and defeat Epirus. This led to a short-lived revival of Byzantine fortunes under Michael VIII Palaiologos, but the war-ravaged empire was ill-equipped to deal with the enemies that now surrounded it. In order to maintain his campaigns against the Latins, Michael pulled troops from Asia Minor, and levied crippling taxes on the peasantry, causing much resentment. Massive construction projects were completed in Constantinople to repair the damages of the Fourth Crusade, but none of these initiatives was of any comfort to the farmers in Asia Minor, who were suffering raids from fanatical ghazis.

Rather than merely holding on to his possessions in Asia Minor, Michael chose to expand the Empire, gaining only short- term success. To avoid another sacking of the capital by the Latins, he forced the Byzantine Church to submit to Rome, again a temporary solution for which the peasantry hated Michael and Constantinople. The efforts of Andronikos II and later his grandson Andronikos III marked Byzantium's last genuine attempts in restoring the glory of the empire. However, the use of mercenaries by Andronikos II would often backfire, with the Catalan Company ravaging the countryside and increasing resentment towards Constantinople.

Rise of the Ottomans and fall of Constantinople:

Things went worse for Byzantium during the civil wars that followed after Andronikos III died. A six-year long civil war devastated the empire, and an earthquake at Gallipoli in 1354 destroyed the fort, allowing the Ottomans (who had been hired as mercenaries during the civil war by John VI Kantakouzenos) to establish themselves in Europe. By the time the Byzantine civil wars had ended, the Ottomans had defeated the Serbians and subjugated them as vassals. Following the Battle of Kosovo, much of the Balkans became dominated by the Ottomans.

The Emperors appealed to the west for help, but the Pope would only consider sending aid in return for a reunion of the Eastern Orthodox Church with the See of Rome. Church unity was considered, and occasionally accomplished by imperial decree, but the Orthodox citizenry and clergy intensely resented the authority of Rome and the Latin Rite. Some western troops arrived to bolster the Christian defense of Constantinople, but most Western rulers, distracted by their own affairs, did nothing as the Ottomans picked apart the remaining Byzantine territories.

Constantinople by this stage was underpopulated and dilapidated. The population of the city had collapsed so severely that it was now little more than a cluster of villages separated by fields. On 2 April 1453, Sultan Mehmed's army of some 80,000 men and large numbers of irregulars laid siege to the city. Despite a desperate last-ditch defense of the city by the massively outnumbered Christian forces (c. 7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were foreign), Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans after a two-month siege on 29 May 1453. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, was last seen casting off his imperial regalia and throwing himself into hand-to-hand combat after the walls of the city were taken.