This

page is on the internet at http://www.mmdtkw.org/GR-Unit9-PoleisDevelopmentColonization.html

Unit

9: Poleis development, colonization

Polis

Polis (;

Greek: πόλις [pólis]), plural poleis

(,

πόλεις [póleːs])

literally means city

in Greek. It can also mean citizenship and body of

citizens. In modern historiography, polis is

normally used to indicate the ancient Greek

city-states, like Classical Athens and its

contemporaries, and thus is often translated as "city-state".

The Ancient Greek city-state

developed during the Archaic

period as the ancestor of city, state, and citizenship and

persisted (though with decreasing influence) well into Roman times, when the equivalent

Latin

word was civitas, also meaning "citizenhood", while

municipium applied to a non-sovereign local

entity. The term "city-state", which originated in

English (alongside the German Stadtstaat), does not

fully translate the Greek term. The poleis

were not like other primordial ancient city-states like Tyre or Sidon,

which were ruled by a king or a small oligarchy, but rather political

entities ruled by their bodies of citizens.

The traditional view of archaeologists—that the appearance

of urbanization at excavation sites

could be read as a sufficient index for the development of a

polis—was criticised by François Polignac in 1984

and has not been taken for granted in recent decades: the polis

of Sparta, for example, was established in a network of

villages. The term polis, which in archaic

Greece meant "city", changed with the development of the

governance center in the city to signify "state" (which

included its surrounding villages). Finally, with the

emergence of a notion of citizenship among landowners, it

came to describe the entire body of citizens. The

ancient Greeks did not always refer to Athens,

Sparta, Thebes, and other poleis

as such; they often spoke instead of the Athenians,

Lacedaemonians, Thebans and so on. The body of citizens came

to be the most important meaning of the term polis

in ancient Greece.

The Greek term that specifically

meant the totality of urban buildings and spaces is

ἄστυ (pronounced [ásty]).

The Emergence of the Greek Polis

There is a great deal of

controversy surrounding the question of why Greek

communities became poleis. Some historians and political

analysts found it inevitable. Aristotle, in fact, claimed

that the polis was the natural situation for mankind. He

defined humans as "beings who by nature live in a polis" (Politics

1253a2-3). However, the polis was a unique Greek invention

and far from inevitable. The specific geography and history

of Greece allowed its conception.

There is a great deal of

controversy surrounding the question of why Greek

communities became poleis. Some historians and political

analysts found it inevitable. Aristotle, in fact, claimed

that the polis was the natural situation for mankind. He

defined humans as "beings who by nature live in a polis" (Politics

1253a2-3). However, the polis was a unique Greek invention

and far from inevitable. The specific geography and history

of Greece allowed its conception.

The polis consisted of the city and its surrounding lands

and communities. The whole area was an individual unit with

self-rule. Unlike the Mycenaean cities of Greek's past,

where the powerless poor answered to the powerful

aristocracy and the godlike king, every citizen was at least

equal under the law. Citizenship was limited to natives, and

only male adult citizens could exercise the vote, but power

was distributed more widely than in any previous political

system.

The polis was most efficient if it was small, since large

groups were hard to coordinate as a decision-making body.

Greek political theorists judged that 5 to 10,000 citizens

was the ideal size of a Greek polis. In such a sized

community, most citizens could at least recognize by face

most other citizens.

Greek geography helped keep communities small. Covered with

mountains and inlets, it provided many natural barriers that

isolated neighboring communities. This isolation both

limited the size of most poleis and made large-scale empire

difficult, so most communities could control their own

destiny.

The fall of Mycenaean power and Greece's dark age also

provided a nurturing environment for developing poleis. The

sudden disappearance of political structure provided a

vacuum of power that was filled by the leaders of local

communities. Each city became master of its own destiny.

Over the course of the Dark Age, kingship vanished, and

power was deposited in the hands of the nobles. As the

fighting power of the Greek hoplite grew, rich men without

distinguished lineage could claim importance in the defence

of their community, and power began to be spread even

further. As the aristocracy declined in power, the formerly

powerless took part in government.

Since so much of the early development of the polis is lost

to history, much of the above is speculation. Still, it is

clear that the absence of central authority, paired with the

individualistic nature of Greek communities, led to the

emergence of the polis.

------------------------------------------------------------

Early Colonization

From http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0009%3Achapter%3D5

Some Greeks had emigrated from the mainland eastward

across the Aegean Sea to settle in Ionia

as early as the ninth century BC. Starting around

750 BC, however, Greeks began to settle even farther

outside the Greek homeland. Within two hundred years,

Greek colonies were established in areas that are today

southern France, Spain, Sicily and southern Italy, and

along North Africa and the coast of the Black Sea.

Eventually the Greek world had perhaps as many as 1,500

different city-states. A scarcity of arable land

certainly gave momentum to emigration from Greece, but

the revival of international trade in

the Mediterranean in this era perhaps provided the

original stimulus for Greeks to leave their homeland,

whose economy was still struggling. Some Greeks

with commercial interests took up residence in foreign

settlements, such as those founded in Spain in this

period by the Phoenicians from Palestine. ...

Like other peoples of

the eastern Mediterranean, Greeks also established their

own trading posts abroad. Traders from Euboea, for

instance, had already established commercial contacts by

800 BC with a community located on the Syrian coast at a

site now called Al Mina. Men wealthy enough to

finance risky expeditions by sea ranged far from home in

search of metals. Homeric poetry testifies to the

basic strategy of this entrepreneurial commodity

trading. In the Odyssey , the goddess

Athena once appears disguised as a metal trader to hide

her identity from the son of the poem's hero: “I

am here at present,” she says to him, “with my ship

and crew on our way across the wine-dark sea to

foreign lands in search of copper; I am carrying iron

now.” By about 775 BC, Euboeans, who seem to

have been particularly active explorers, had also

established a settlement for purposes of trade on the

island of Ischia, in the bay of Naples off southern

Italy. There they processed iron ore imported from the

Etruscans, who lived in central Italy. Archaeologists

have documented the expanding overseas communication of

the eighth century by finding Greek pottery at more than

eighty sites outside the Greek homeland ....

---------------------------------------------------------

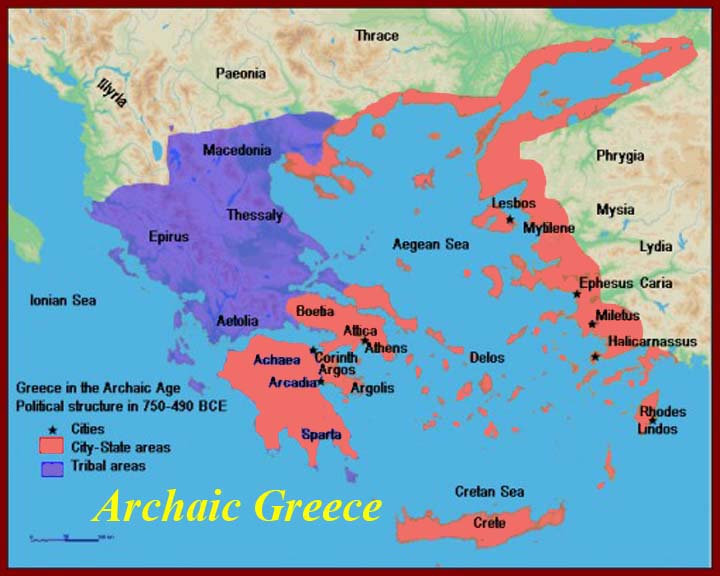

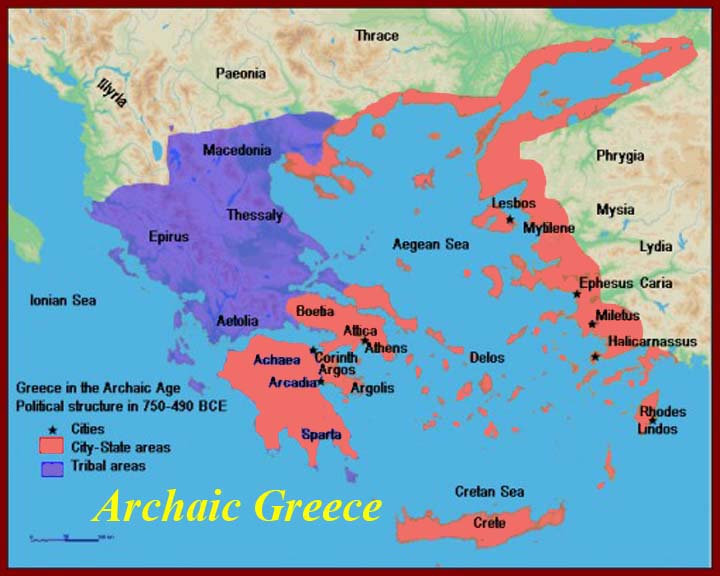

Parts of archaic Greece had the appearance of city

states already toward the end of the "Dark Age" and many

other parts rapidly joined the list. We

should remember that, in the Archaic Period, both coasts

of the Aegean Sea and the whole shoreline of the Sea of

Marmara were Greek. And During the Archaic Period,

colonies spread Greek presence much further. As

noted above, the Eubeans had established what is

considered to be the first Greek colony on Ischia Island

in the Bay of Naples.

Athens and Sparta -- two divergent

examples of polis development

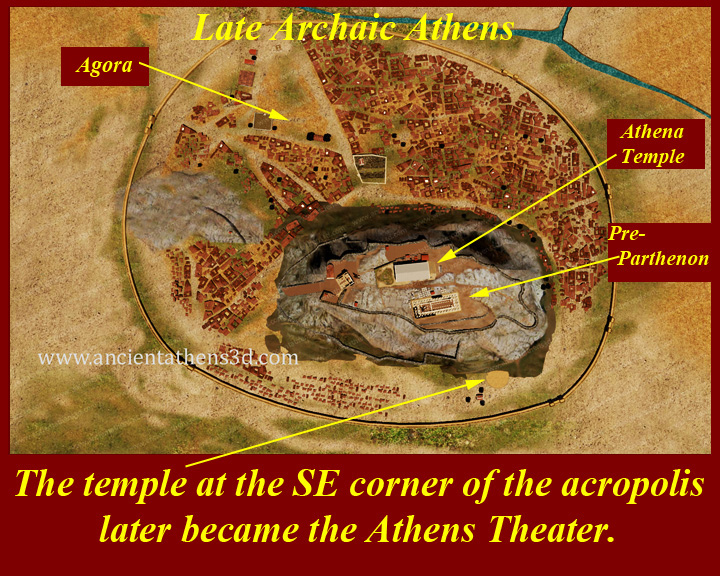

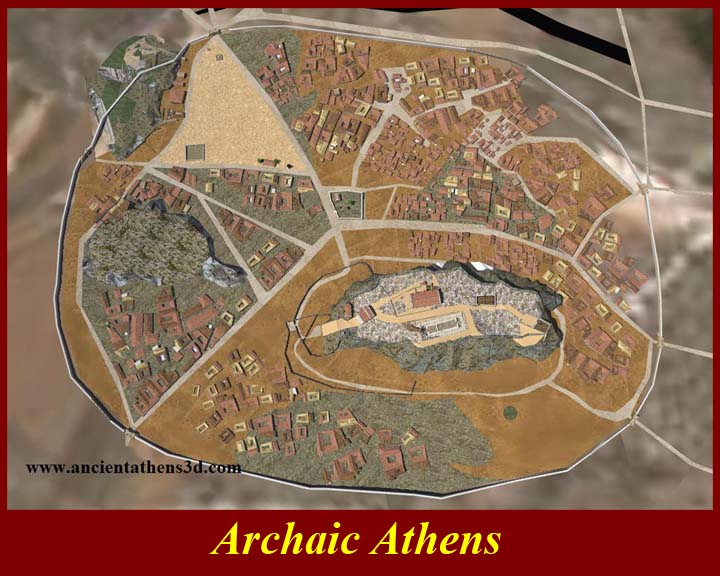

Athens

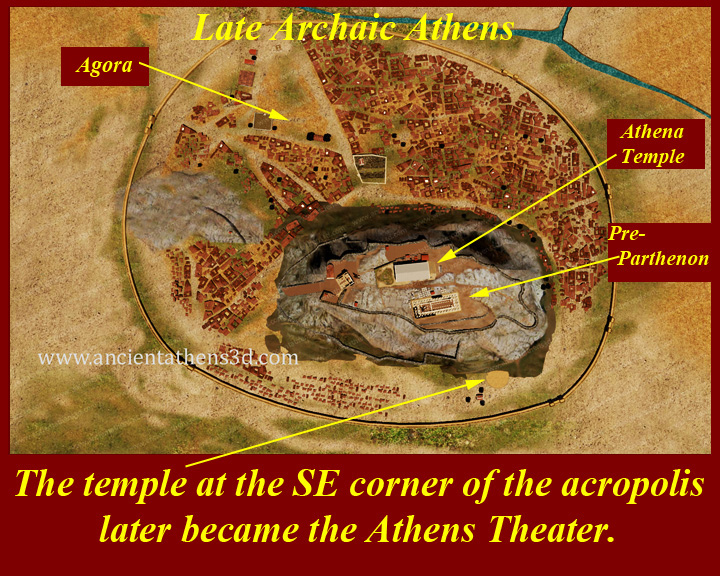

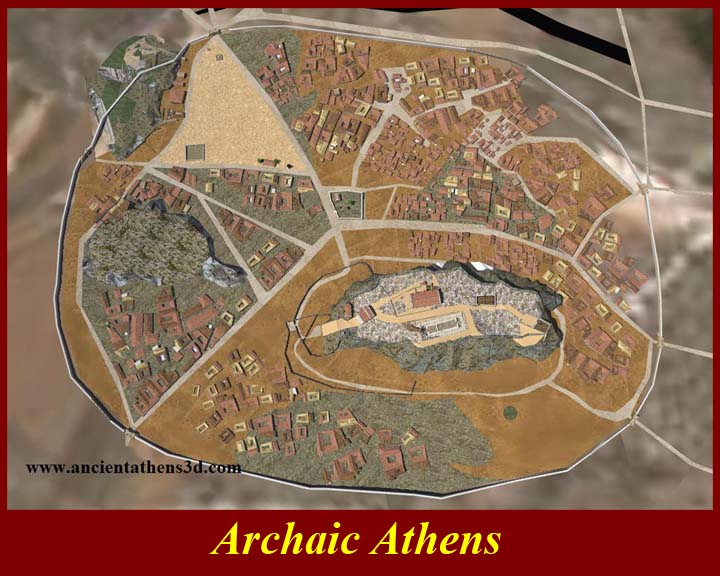

Drawings of overhead views of Archaic Athens.

Unlike many other Bronze Age sites, Athens was not

abandoned at the end of that period. It remained

an urban center throughout the Dark Age.

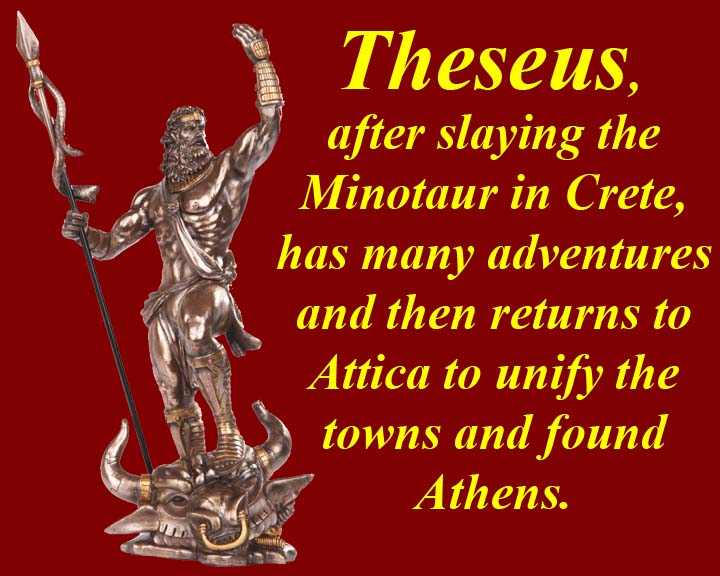

Every city needs a founding myth. Theseus (Ancient

Greek: Θησεύς) was the mythical founder-king of Athens

and was the son of Aethra by two fathers: Aegeus and

Poseidon (double paternity caused by consecutive coitus

was not uncommon in Greek mythology and is, in fact,

possible).

According to the myth, after slaying the Minotaur and

decapitating the beast, Theseus used the string given to

him by Ariadne, the daughter of the Cretan king, Minos,

to find his way out of the Labyrinth and managed to

escape with all of the young Athenians and with Ariadne

as well as her younger sister Phaedra. On the beach, he and the rest of the crew fell

asleep. Athena woke Theseus and told him to leave

early that morning. She told Theseus to leave

Ariadne and Phaedra on the beach. Stricken with

distress, Theseus forgot to put up the white sails

instead of the black ones, so Aegeus committed suicide,

in some versions throwing himself off a cliff and into

the sea, thus causing this body of water to be named the

Aegean. Theseus went on to gather the Attic

peoples and found a polis, which, under the protection

of Athena became Athens.

According to Plutarch's Life of Theseus, the ship

Theseus used on his return from Crete to Athens was kept

in the Athenian harbor as a memorial for several

centuries.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theseus

for more of the Theseus mythology.

There are all kinds of inconsistencies and anachronisms

in this Athens founding myth, but that also was not uncommon in such

stories.

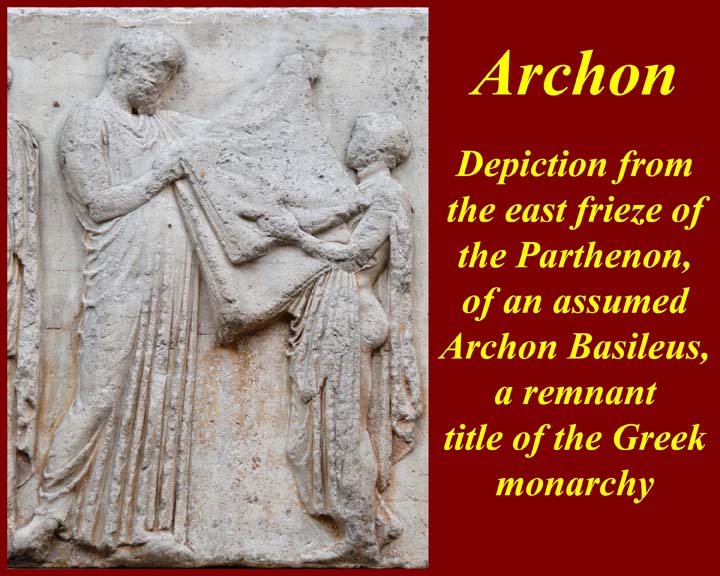

Archon (Greek ἄρχων arkhon; pl. ἄρχοντες) is a Greek

word that means "ruler" or "lord," frequently used as

the title of a specific public office. It is the

masculine present participle of the verb stem ἀρχ-,

meaning "to rule," derived from the same root as

monarch.

In ancient Greece the chief magistrate in various Greek

city states was called Archon. The term was also used

throughout Greek history in a more general sense.

In Athens a republican system of nine concurrent Archons

evolved, led by three respective remits over the civic,

military, and religious affairs of the state: the three

office holders being known as the Eponymos archon

(Ἐπώνυμος ἄρχων; the "name" ruler, who gave his name to

the year in which he held office), the Polemarch ("war

ruler"), and the Archon Basileus ("king ruler").[1] The

six others were the Thesmothétai, Judicial Officers.

Originally these offices were filled from the wealthier

classes by elections every ten years. During this period

the eponymous Archon was the chief magistrate, the

Polemarch was the head of the armed forces, and the

Archon Basileus was responsible for some civic religious

arrangements, and for the supervision of some major

trials in the law courts. After 683 BC the offices were

held for only a single year, and the year was named

after the Archōn Epōnymos. (Many ancient calendar

systems did not number their years consecutively.)

After 487 BC, the archonships were assigned by lot to

any citizen and the Polemarch's military duties were

taken over by new class of generals known as

stratēgoí.[citation needed] The ten stratēgoí (one per

tribe) were elected, and the office of Polemarch was

rotated among them on a daily basis. The Polemarch

thereafter had only minor religious duties, and the

titular headship over the strategoi. The Archon Eponymos

remained the titular head of state under democracy,

though of much reduced political importance.[citation

needed] The Archons were assisted by "junior" archons,

called Thesmothétai (Θεσμοθέται "Institutors"). After

457 BC ex-archons were automatically enrolled as life

members of the Areopagus, though that assembly was no

longer extremely important politically at that time.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archon

and links on that Internet page.

Athenian Law:

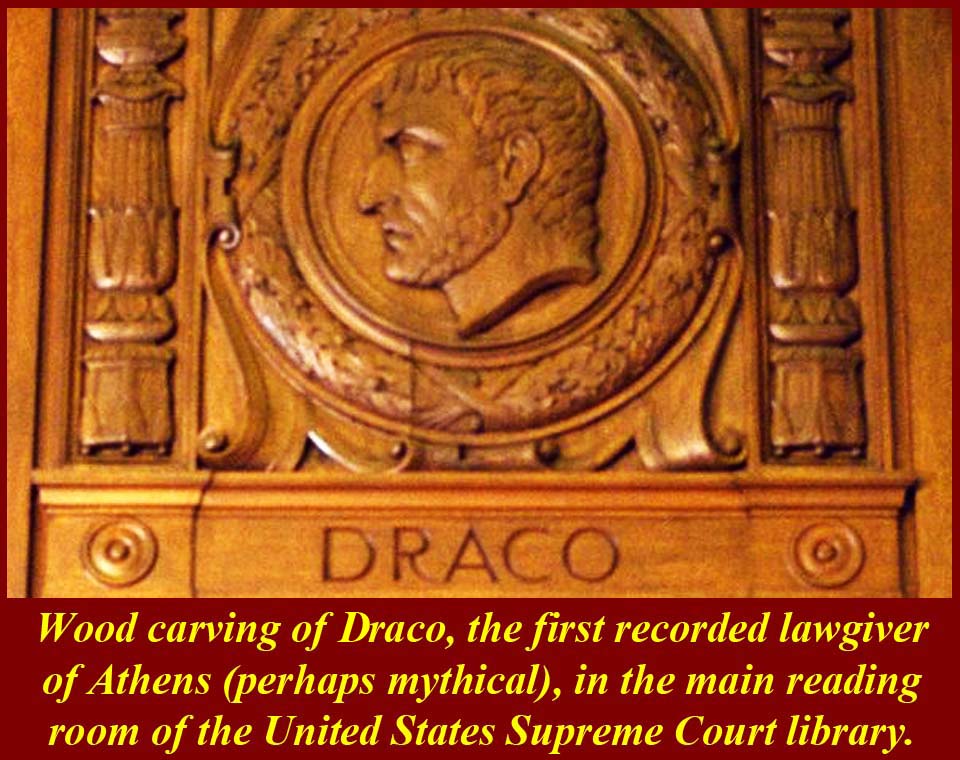

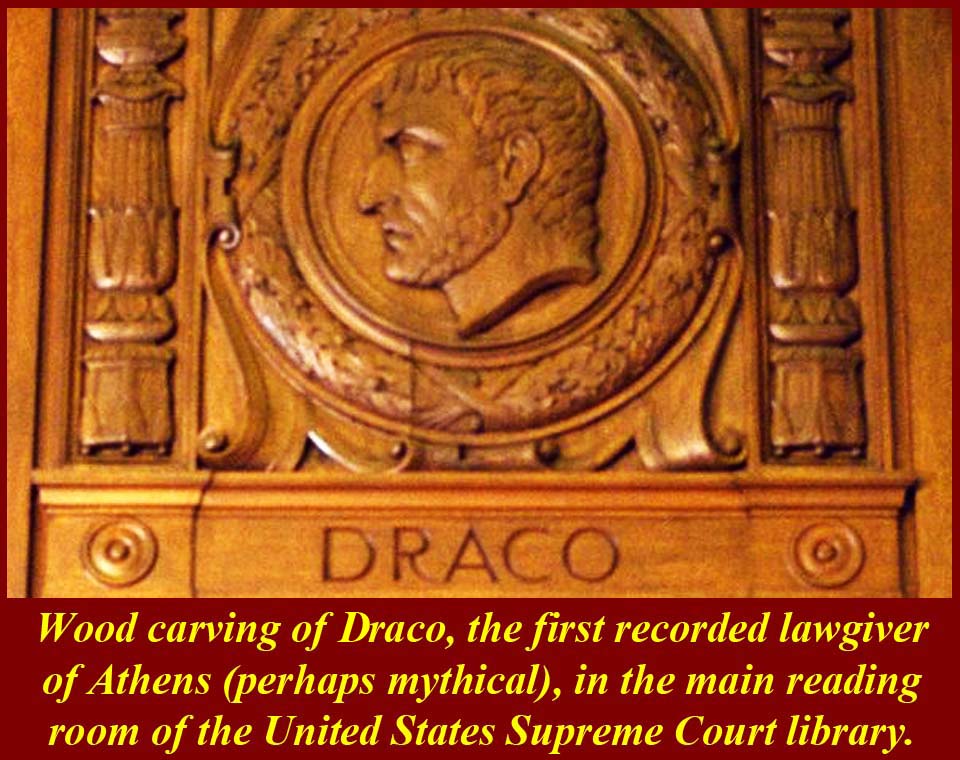

Draco /Greek: Δράκων, Drakōn; fl. c. 7th century BC) was

the first legislator of Athens in Ancient Greece.

During the 39th Olympiad, in 622 or 621 BC, Draco

established the legal code with which he is

identified. He replaced the prevailing system of

oral law and blood feud by a written code to be enforced

only by a court. His laws, however were

"Draconian", i.e., even minor offenses could bring the

death penalty. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Draco_(lawgiver).

Solon (Greek: Σόλων; c. 638 – c. 558 BC) was an Athenian

statesman, lawmaker, and poet. He is remembered

particularly for his efforts to legislate against

political, economic, and moral decline in archaic

Athens. His reforms failed in the short term, yet

he is often credited with having laid the foundations

for Athenian democracy. He wrote poetry for

pleasure, as patriotic propaganda, and in defense of his

constitutional reforms. See

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solon.

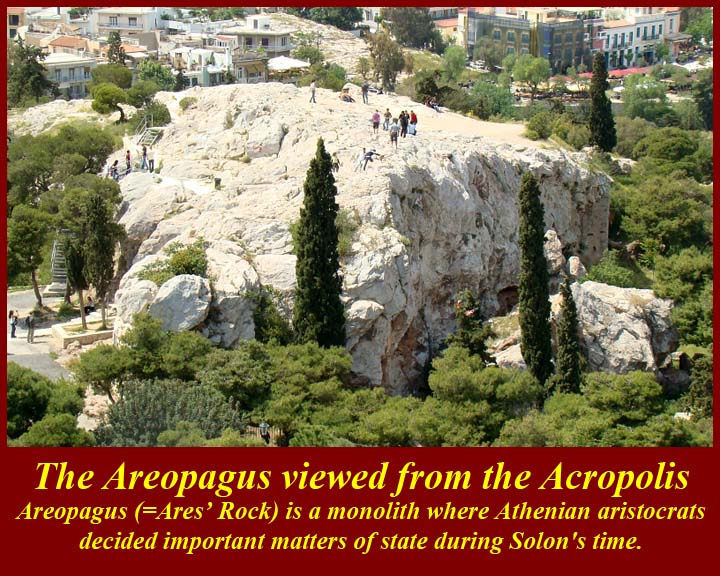

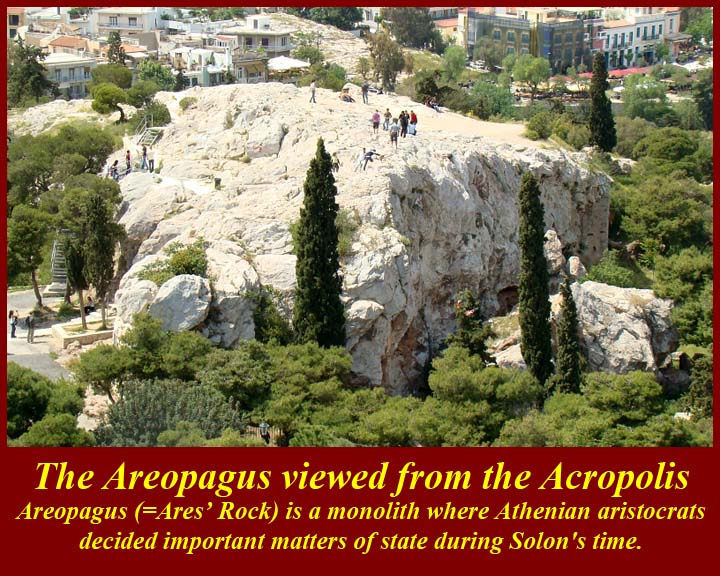

Areopagus -- Athenian Rock and Greek council

Written by: The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica http://www.britannica.com/topic/Areopagus-Greek-council

Alternative titles: Areopagite Council; Council of the

Hill of Ares

Areopagus, earliest aristocratic council of

ancient Athens. The name was taken from the Areopagus

(“Ares’ Hill”), a low hill northwest of the Acropolis,

which was its meeting place. [tkw note: the low hill is

actually a marble outcrop as shown in the image.]

The Areopagite Council probably began as the king’s

advisers. Early in the Archaic period it exercised a

general and ill-defined authority until the publication

of Draco’s Code of Law (c. 621). Membership continued

for life and was secured by having served as archon, an

office limited to the eupatrids (Greek: eupatridai,

“nobles by birth”). Under Solon (archon 594 bc), the

composition and authority of the council were materially

altered when the archonship was opened to all with

certain property qualifications, and a Boule, a rival

council of 400, was set up. The Areopagus nevertheless

retained “guardianship of the laws” (perhaps a

legislative veto); it tried prosecutions under the law

of eisangelia (“impeachment”) for unconstitutional acts.

As a court under the presidency of the archōn basileus,

it also decided cases of murder.

For about 200 years, from the middle of the 6th century

bc, the prestige of the Areopagus fluctuated. The fall

of the Peisistratids, who during their tyranny (546–510)

had filled the archonships with their adherents, left

the Areopagus full of their nominees and thus in low

esteem; its reputation was restored by its patriotic

posture during the Persian invasion. In 462 the reformer

Ephialtes deprived the Areopagus of virtually all its

powers save jurisdiction on homicide (c. 462). From the

middle of the 4th century bc, its prestige revived once

again, and by the period of Roman domination in Greece

it was again discharging significant administrative,

religious, and educational functions.

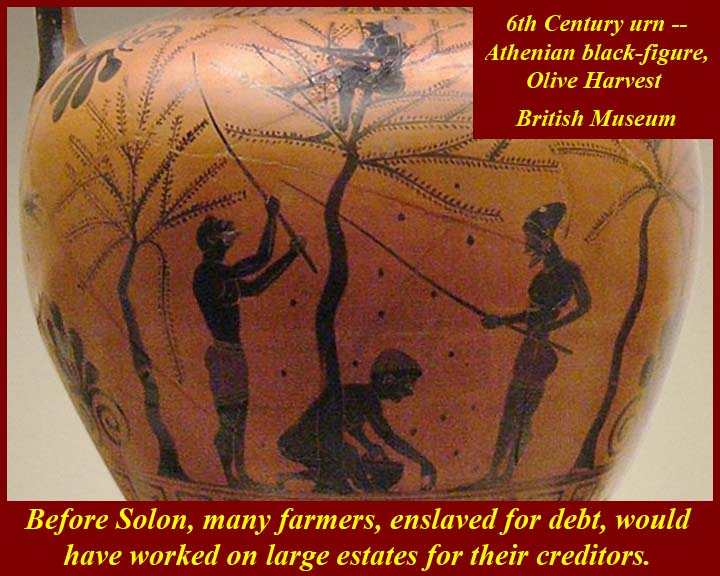

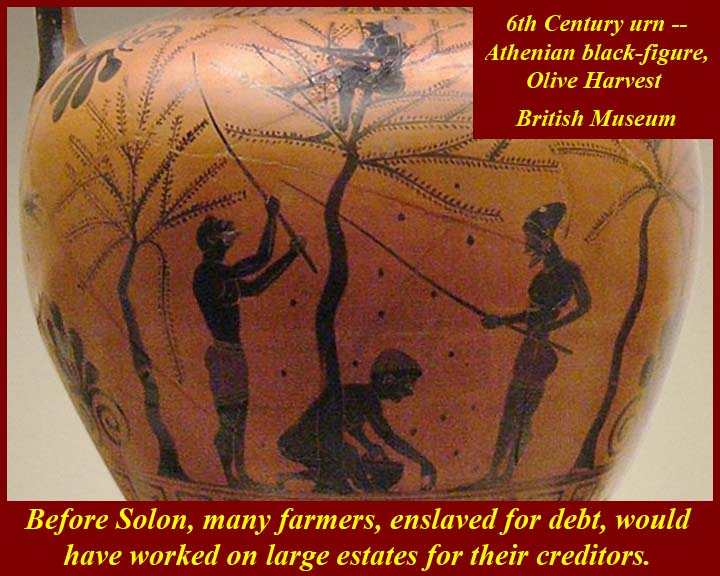

Solon's reforms did succeed in removing personal and

family member debt slavery, which had been a large

source of labor on creditors' farms.

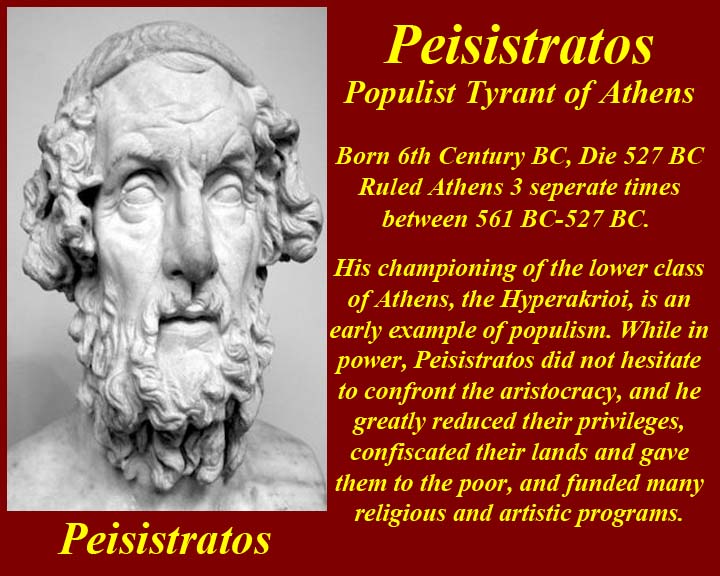

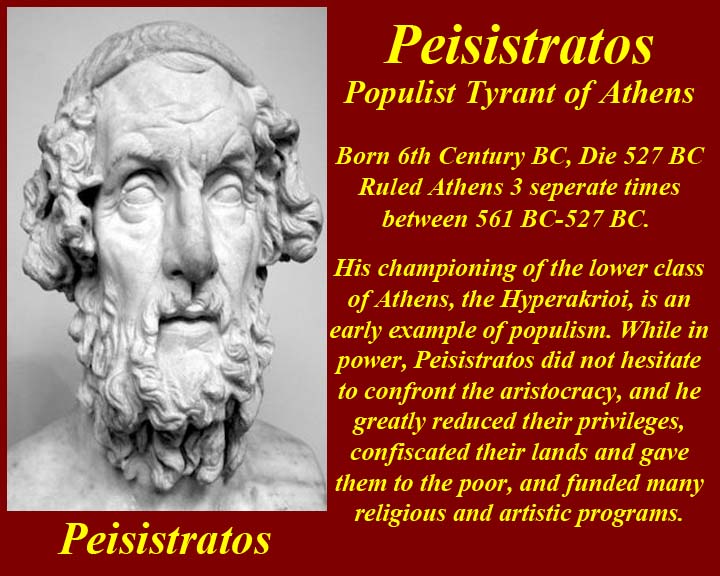

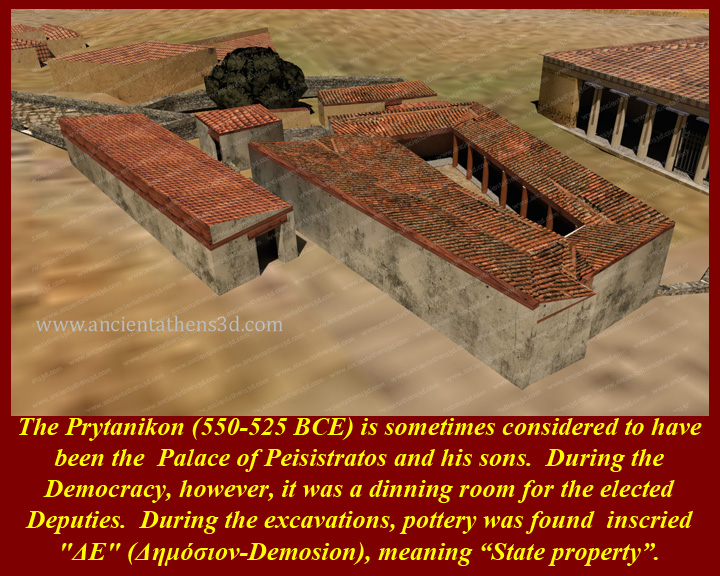

Peisistratos (/paɪˈsɪstrətəs/; Greek: Πεισίστρατος; died

528/7 BCE), latinized Pisistratus, the son of

Hippocrates, was a ruler of ancient Athens during most

of the period between 561 and 527 BCE. His legacy

lies primarily in his institution of the Panathenaic

Festival and the consequent first attempt at producing a

definitive version of the Homeric epics.

Peisistratos' championing of the lower class of Athens,

the Hyperakrioi, is an early example of populism.

While in power, Peisistratos did not hesitate to

confront the aristocracy, and he greatly reduced their

privileges, confiscated their lands and gave them to the

poor, and funded many religious and artistic programs.

Peisistratids is the common term for the three tyrants

who ruled in Athens from 546 to 510 BC, namely

Peisistratos and his two sons, Hipparchus and Hippias.

Pisistratus's main policies were aimed at strengthening

the economy, and similar to Solon, he was concerned

about both agriculture and commerce. He offered

land and loans to the needy. He encouraged the

cultivation of olives and the growth of Athenian trade,

finding a way to the Black Sea and even Italy and

France. Under Peisistratus, fine Attic pottery

traveled to Ionia, Cyprus, and Syria. In Athens,

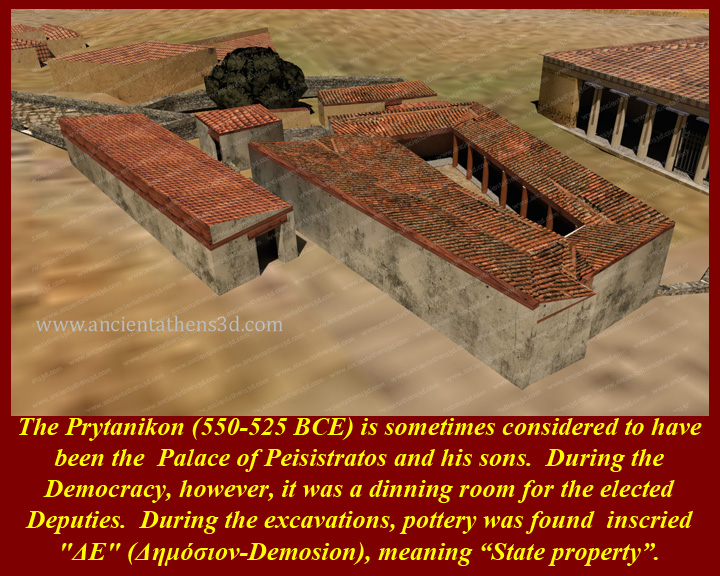

Pisistratus' public building projects provided jobs to

people in need while simultaneously making the city a

cultural center. He replaced the private wells of

the aristocrats with public fountain houses.

Pisistratos also built the first aqueduct in Athens,

opening a reliable water supply to sustain the large

population.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peisistratos

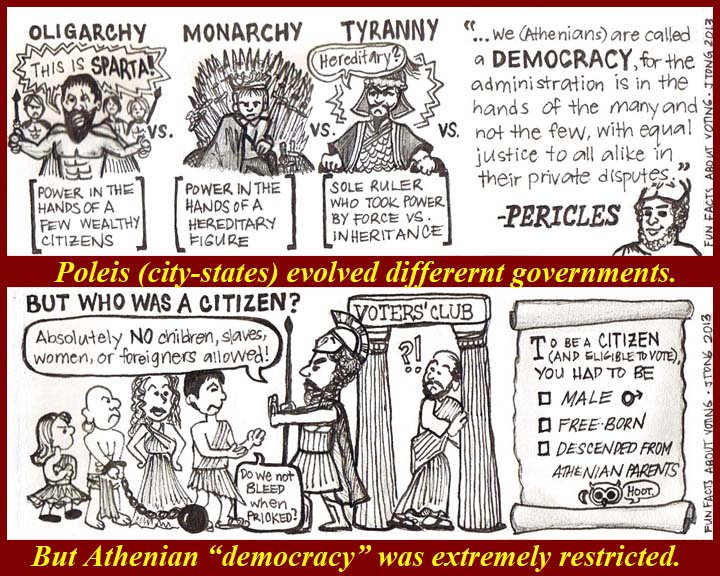

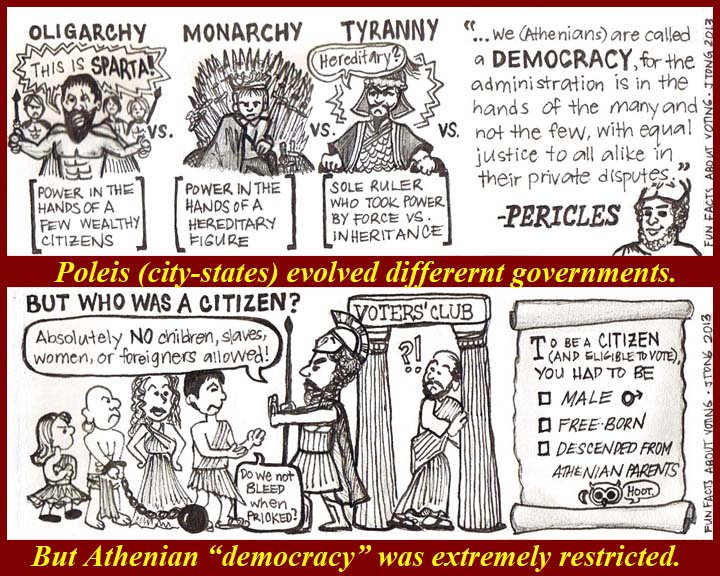

All of the possible forms of government available to the

Athenians were problematic. Much vaunted Athenian

democracy was extremely restricted; only male adults

both of whose parents were citizens could participate in

Athenian political life. (The cartoon is, in

fact, incorrect -- females with proper parentage

could be "citizens", but they were not allowed to

exercise their citizenship except by

producing more citizens.

Athenian democracy developed around the fifth century BC

in the Greek city-state (known as a polis) of Athens,

comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding

territory of Attica and is the first known democracy in

the world. Other Greek cities set up democracies, most

following the Athenian model, but none are as well

documented as Athens.

It was a system of direct democracy, in which

participating citizens voted directly on legislation and

executive bills. Participation was not open to all

residents: to vote one had to be an adult, male citizen,

and the number of these "varied between 30,000 and

50,000 out of a total population of around 250,000 to

300,000.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athenian_democracy.

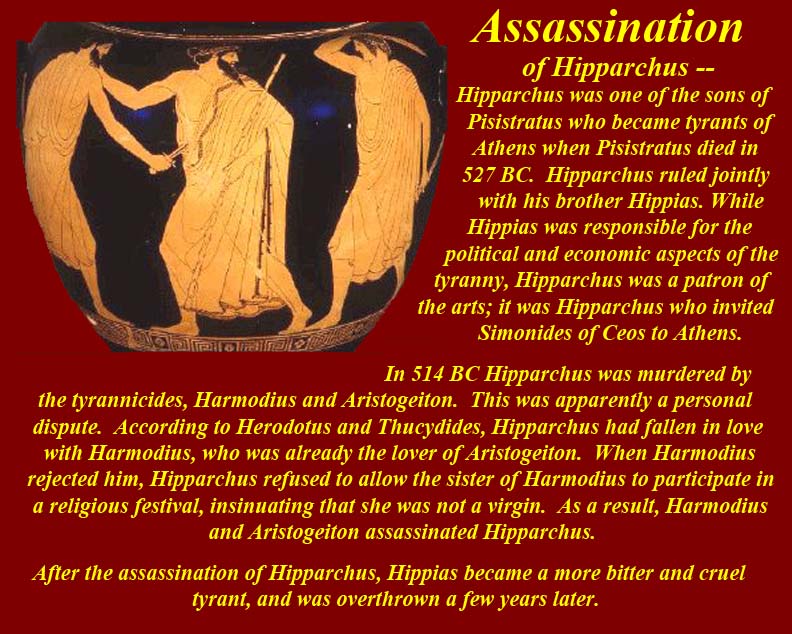

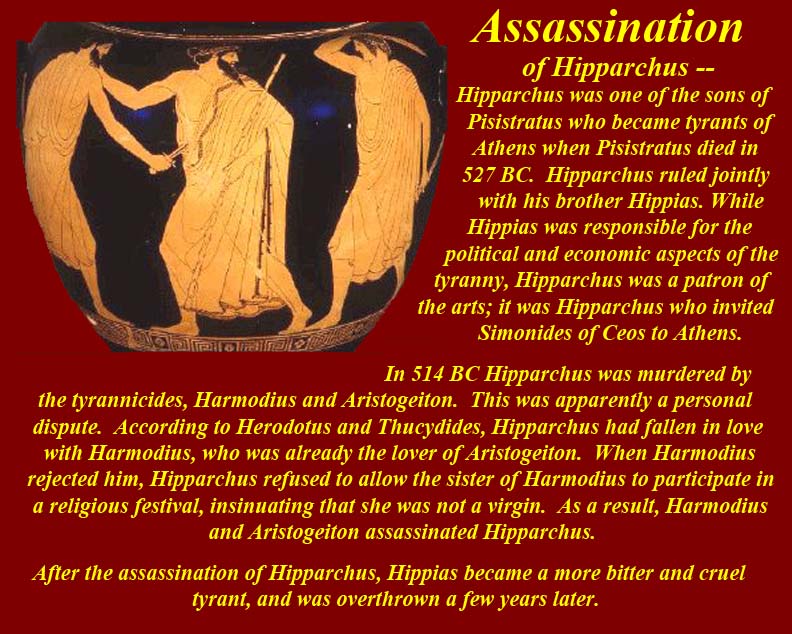

Peisistratos died in 527 or 528 BC. He was succeeded by

his eldest son, Hippias. Hippias and his brother,

Hipparchus, ruled the city much as their father

did. After a successful murder plot against

Hipparchus conceived by Harmodius and Aristogeiton,

Hippias became paranoid and oppressive. This

change caused the people of Athens to hold Hippias in

much lower regard. The Alcmaeonid family helped

depose the tyranny by bribing the Delphic oracle to tell

the Spartans to liberate Athens, which they did in 508

BC. The Peisistratids were not executed, but

rather were mostly forced into exile. Afterwards,

the surviving Peisistratid, Hippias went on to aid the

Persians with their attack on Marathon acting as a

guide.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peisistratos

and http://www.britannica.com/biography/Peisistratus.

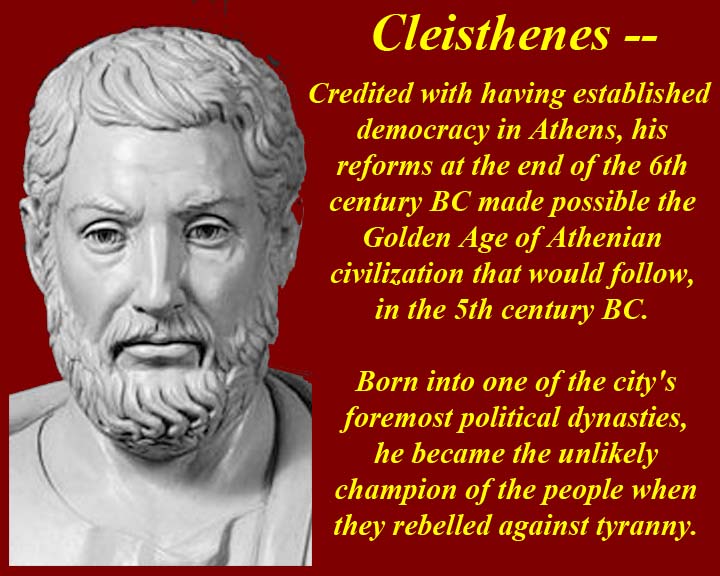

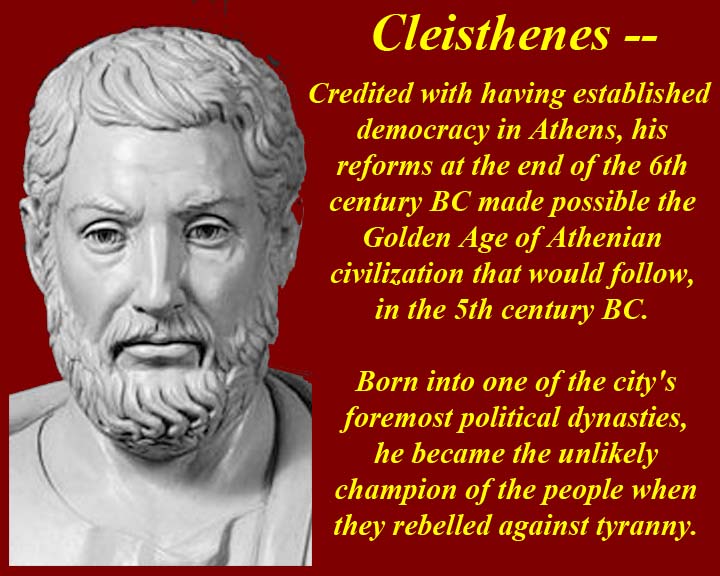

Cleisthenes of Athens, also spelled Clisthenes

(born c. 570 bce—died c. 508), statesman regarded as the

founder of Athenian democracy, serving as chief archon

(highest magistrate) of Athens (525–524).

Cleisthenes successfully allied himself with the popular

Assembly against the nobles (508) and imposed democratic

reform. Perhaps his most important innovation was

the basing of individual political responsibility on

citizenship of a place rather than on membership in a

clan.

See http://www.britannica.com/biography/Cleisthenes-of-Athens

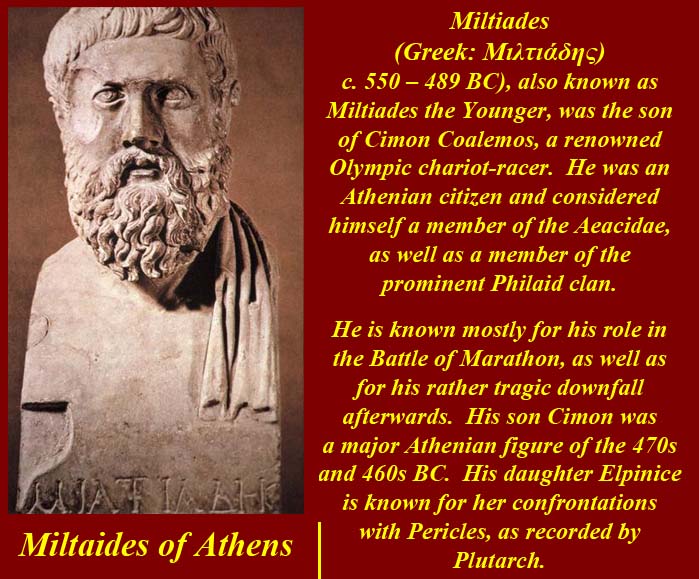

Miltiades was an Athenian who inherited the position of

tyrant a colony on the Thracian Chersonese (now the

Gallipoli Peninsula) where he ruled harshly. After the

collapse of the Ionian revolt against Persia (494 BC),

Miltiades and his clan fled back to Athens, taking

shiploads of wealth with them. The Athens to which

Miltiades returned was no longer a tyranny, it had

overthrown the Peisistratids and become a democracy 15

years earlier. Thus, Miltiades initially faced a hostile

reception for his tyrannical rule in the Thracian

Chersonese. Miltiades successfully presented

himself as a defender of Greek freedoms against Persian

despotism, and also promoted the fact that he had been a

first-hand witness to Persian tactics, a useful resume

considering the Persians were bent on destroying the

city, and so Miltiades escaped punishment and was

allowed to rejoin his old countrymen.

Miltiades is often credited with devising the tactics

that defeated the Persians in the Battle of

Marathon. Miltiades was elected to serve as one of

the ten generals (strategoi) for 490 BC. In

addition to the ten generals, there was one 'war-ruler'

(polemarch), Callimachus, who had been left with a

decision of great importance. The ten generals

were split, five to five, on whether to attack the

Persians at Marathon then, or later. Miltiades

was firm in insisting that the Persians be fought

immediately as a siege of Athens would have led to its

destruction, and convinced Callimachus to use his

decisive vote to support the necessity of a swift

attack.

He also convinced the generals of the necessity of not

using the customary tactics, as hoplites usually marched

in an evenly distributed phalanx of shields and spears,

a standard with no other instance of deviation until

Epaminondas. Miltiades feared the cavalry of the

Persians attacking the flanks, and asked for the flanks

to have more hoplites than the centre. Miltiades

had his men march to the end of the Persian archer range

then break out in a run straight at the Persian

army. This was very successful in defeating the

Persians, who then tried to sail around the Cape Sounion

and attack Attica from the west. Miltiades got his

men to quickly march to the western side of Attica

overnight, causing Darius to flee at the sight of the

soldiers who had just defeated him the previous evening.

The following year, 489 BC, Miltiades led an Athenian

expedition of seventy ships against the Greek-inhabited

islands that were deemed to have supported the Persians.

The expedition was not a success. His true

motivations were to attack Paros, feeling he had been

slighted by them in the past. The fleet attacked

the island, which had been conquered by the Persians,

but failed to take it. Miltiades suffered a

serious leg wound during the campaign and became

incapacitated.

His failure prompted an outcry on his return to Athens,

enabling his political rivals to exploit his fall from

grace. Charged with treason, he was sentenced to death,

but the sentence was converted to a fine of fifty

talents. He was sent to prison where he died, probably

of gangrene from his wound.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miltiades

and http://www.britannica.com/biography/Miltiades-the-Younger.

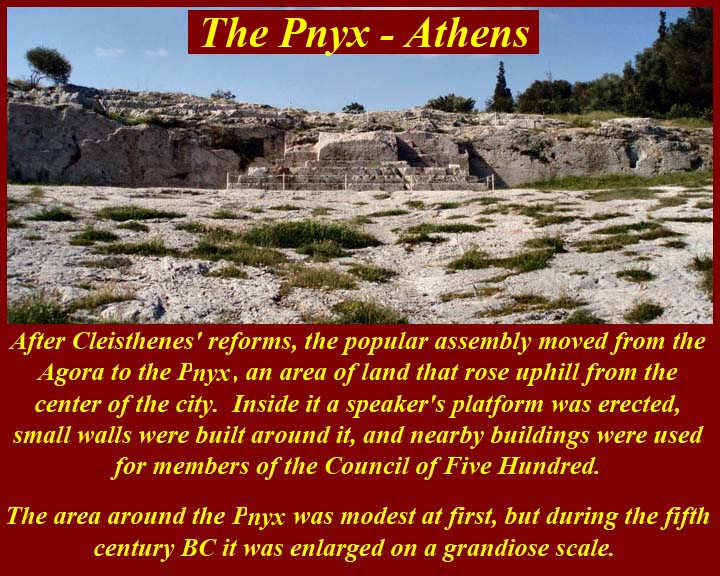

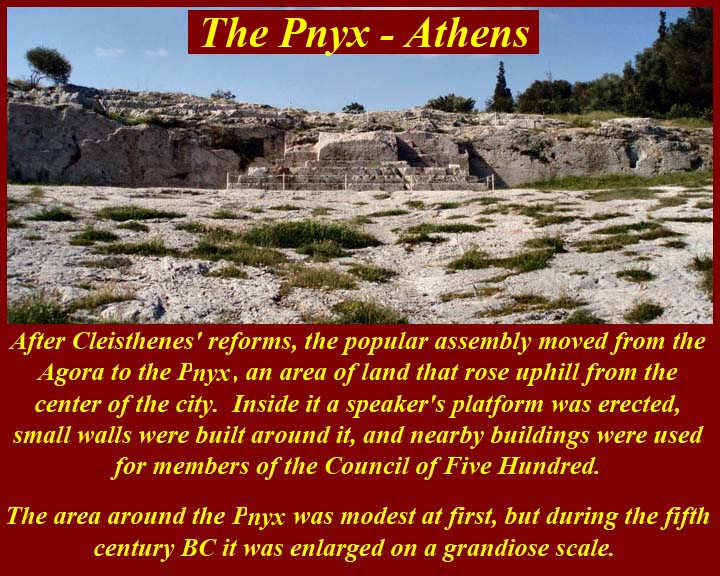

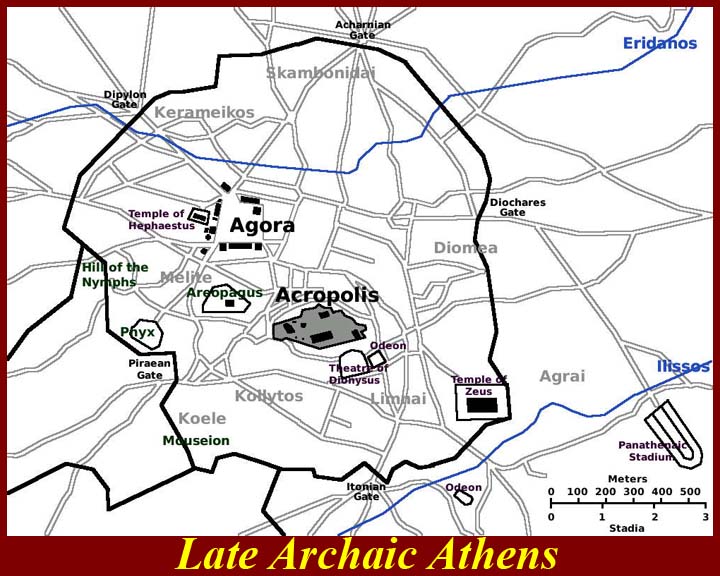

The pnyx was the rock platform in Athens where the

popular assembly convened. Any citizen could speak

at the assembly and voting was done by dropping white or

black pebbles int the ballot box.

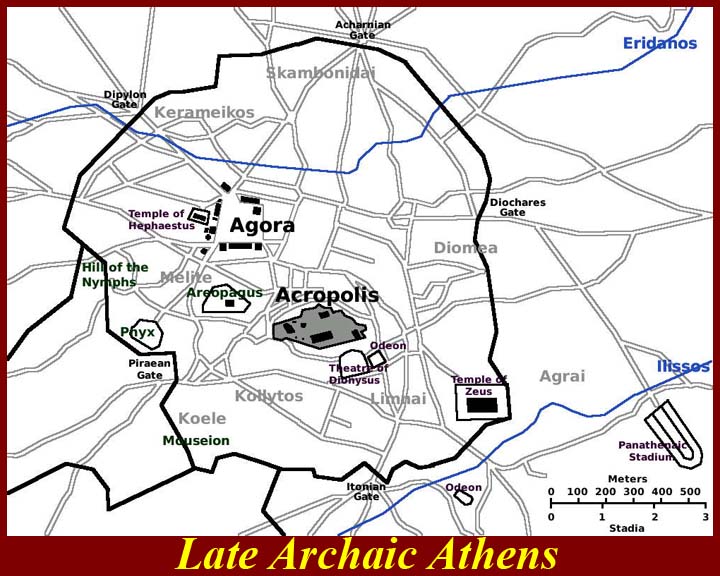

Major locations in Archaic Athens

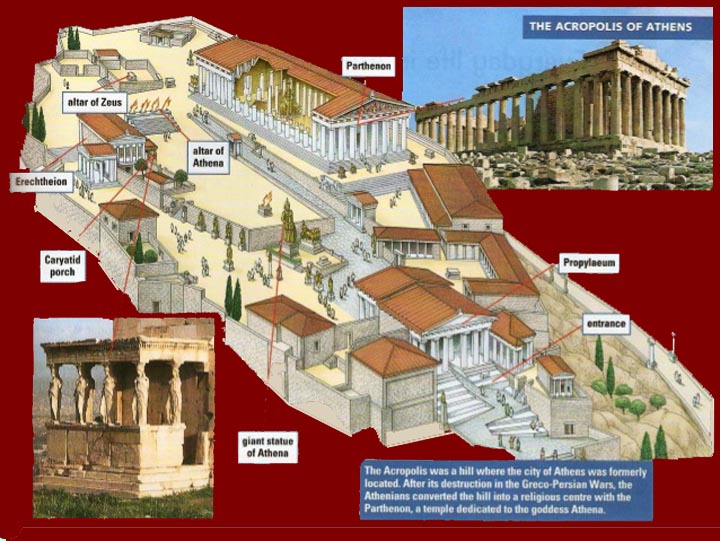

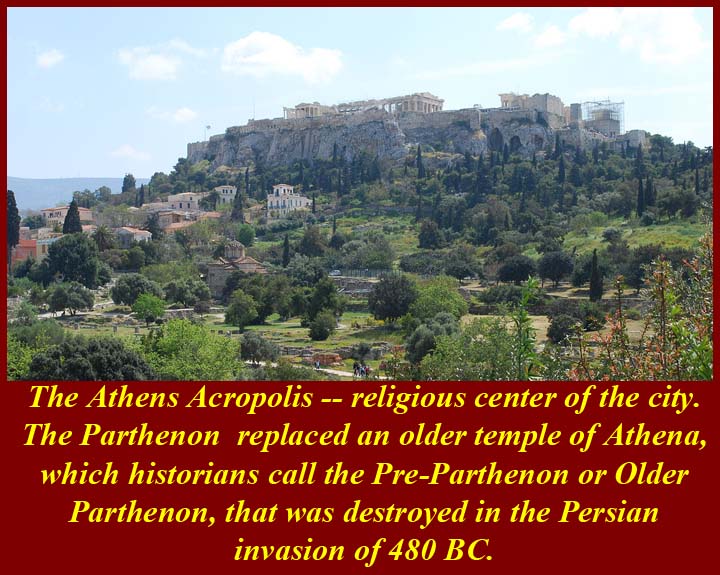

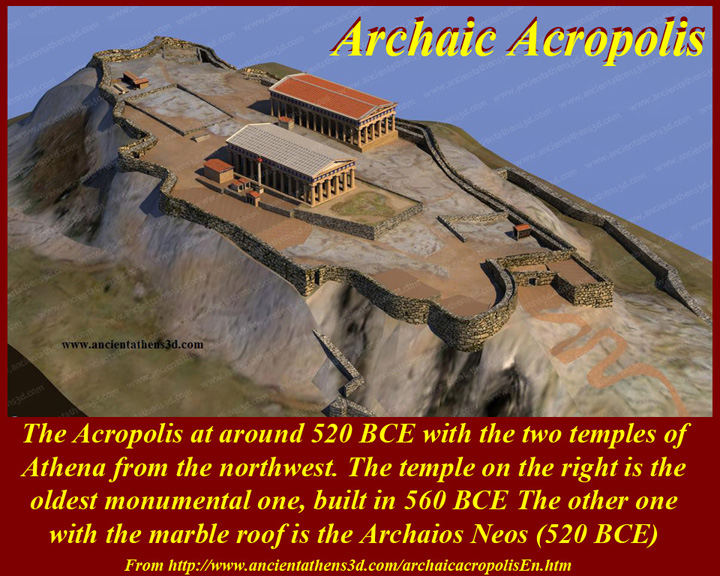

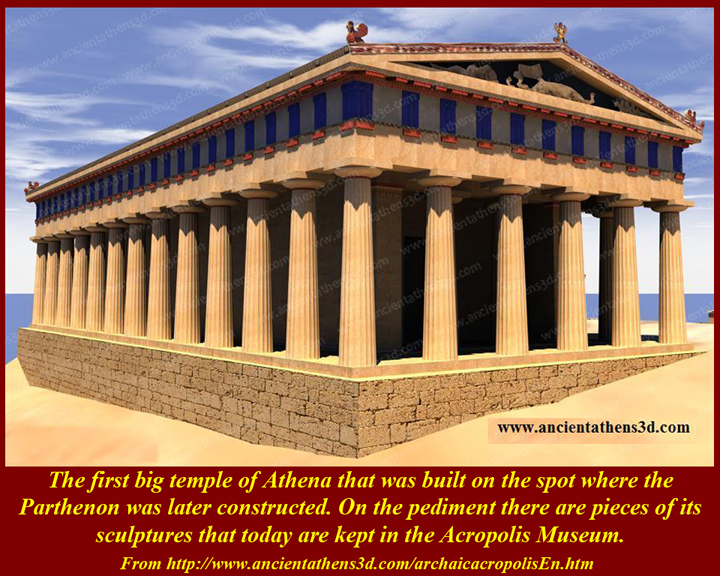

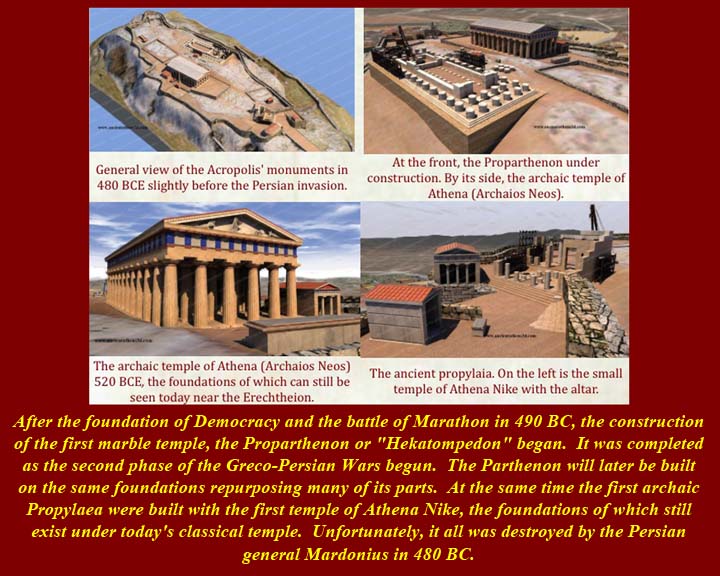

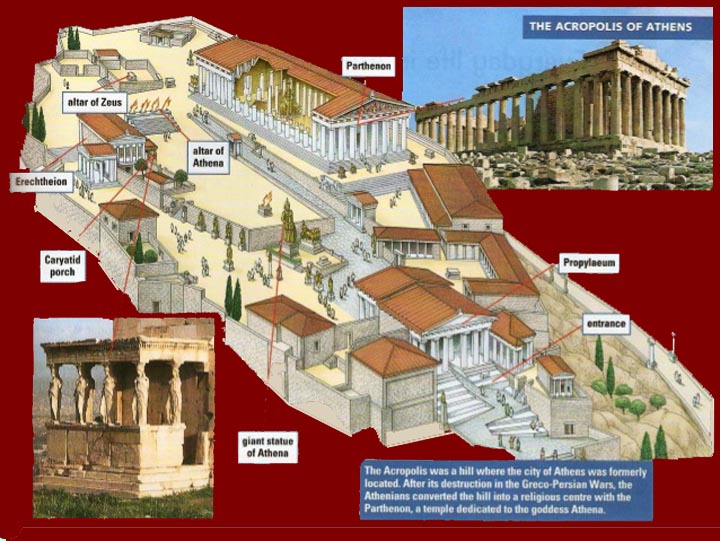

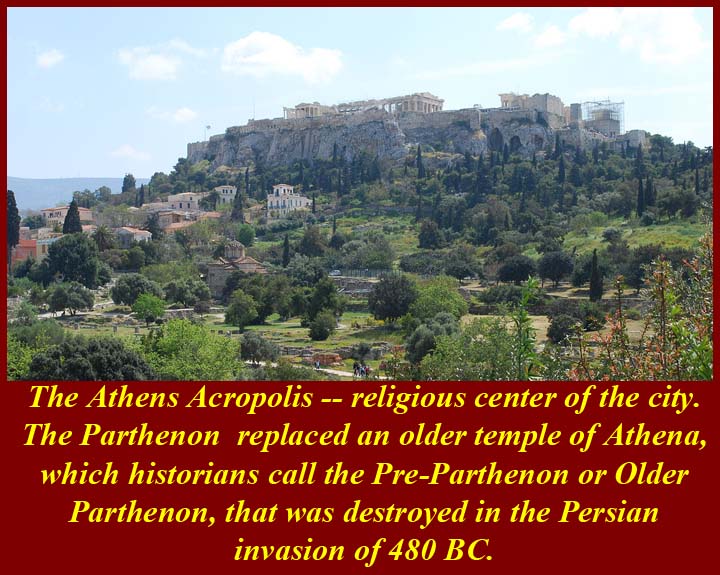

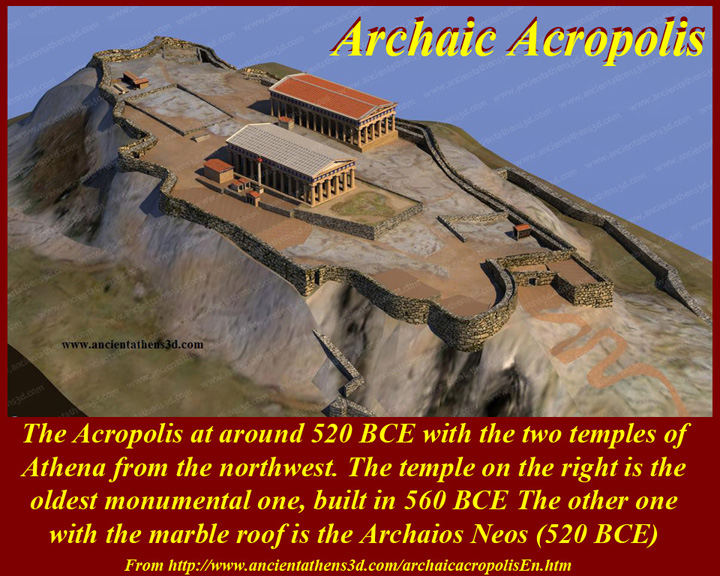

Acropolis

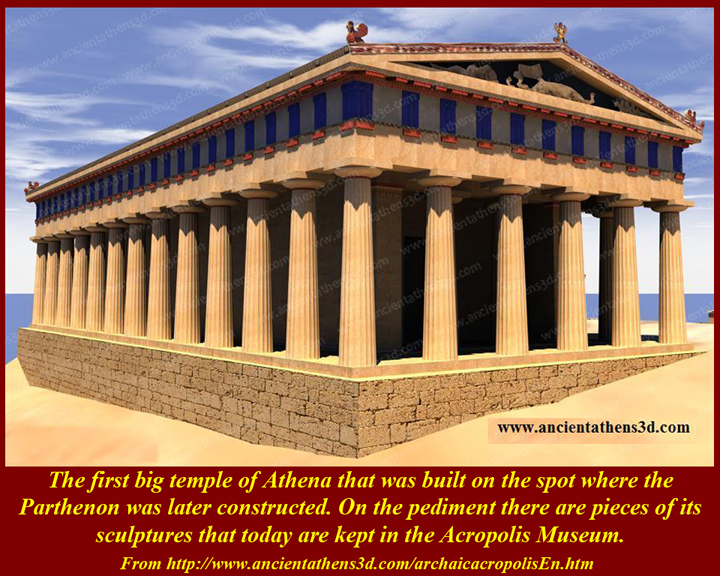

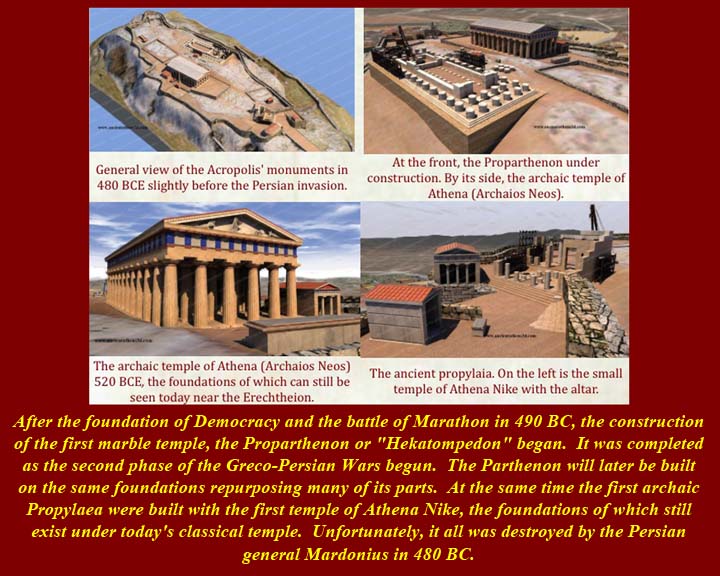

Read about the development of the Athens Acropolis at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acropolis_of_Athens.

For more images and more extensive explanations of the

Archaic Period Acropolis, see http://www.ancientathens3d.com/archaicacropolisEn.htm

and http://ancient-greece.org/history/acropolis.html.

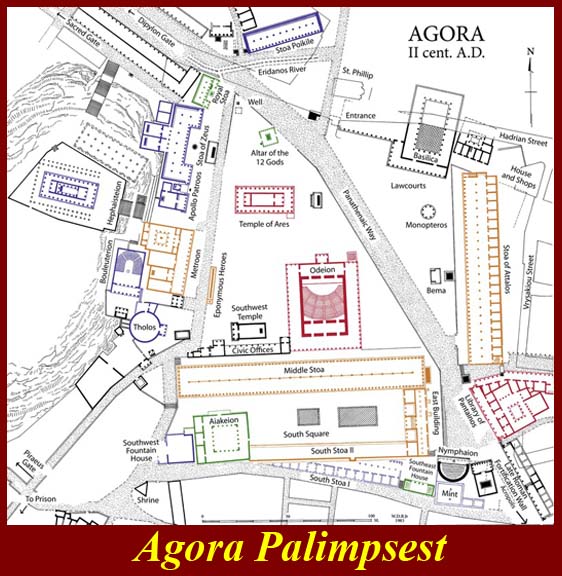

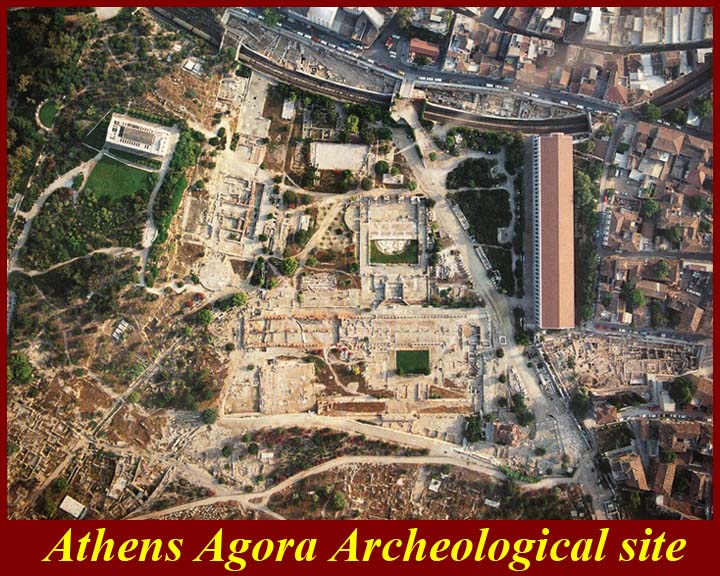

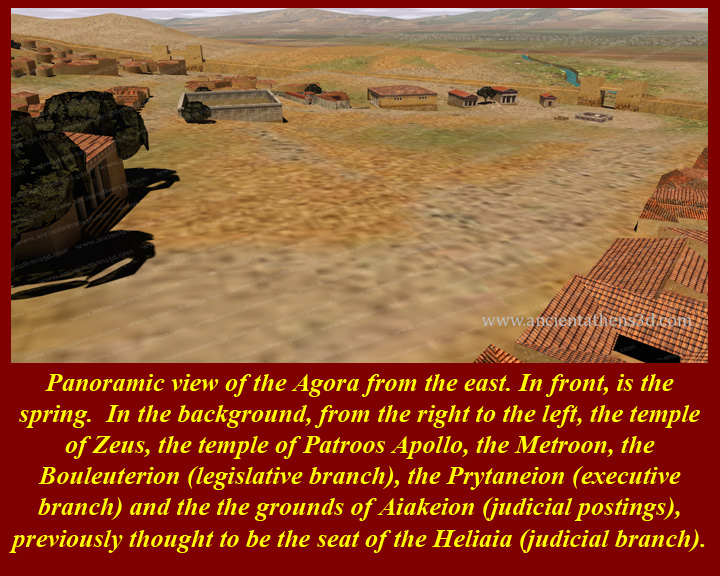

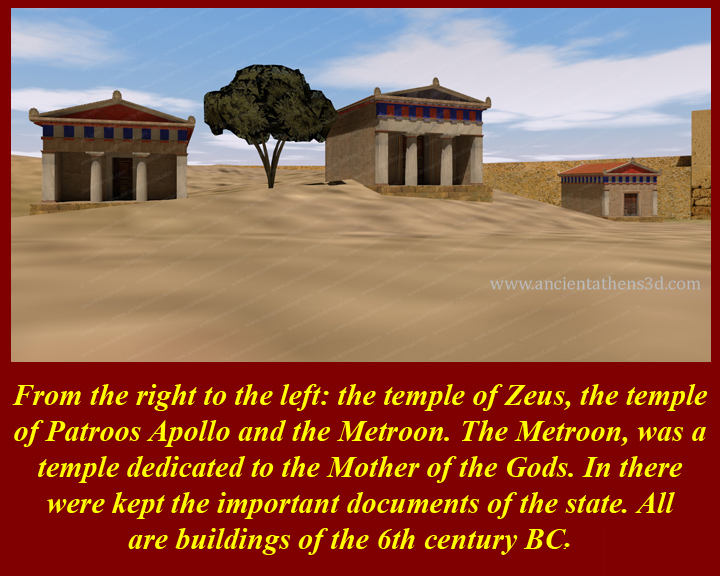

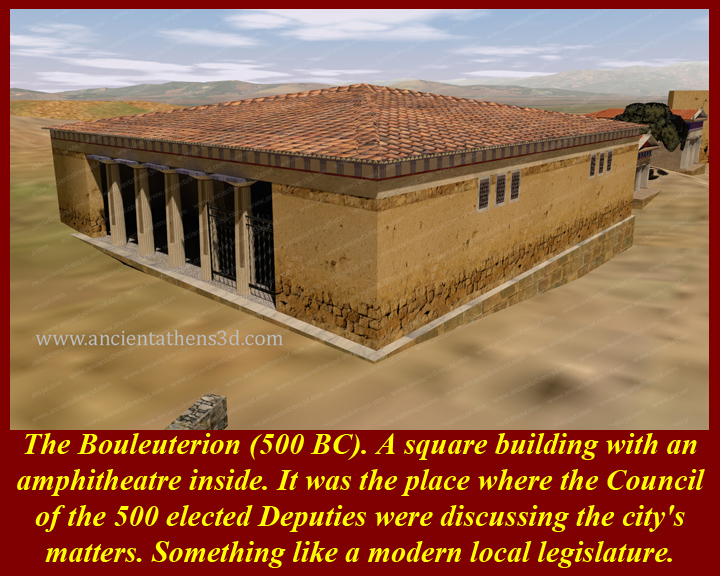

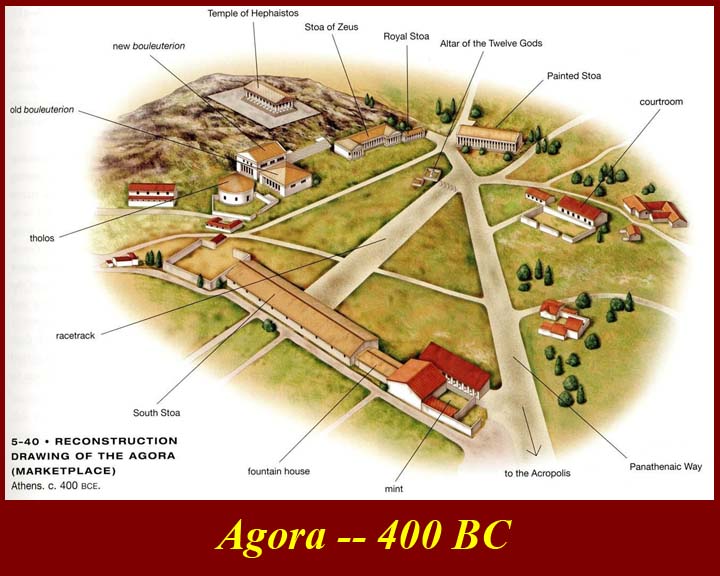

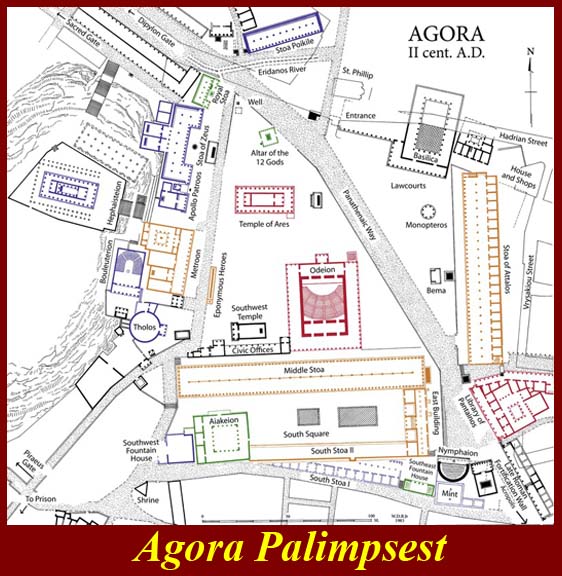

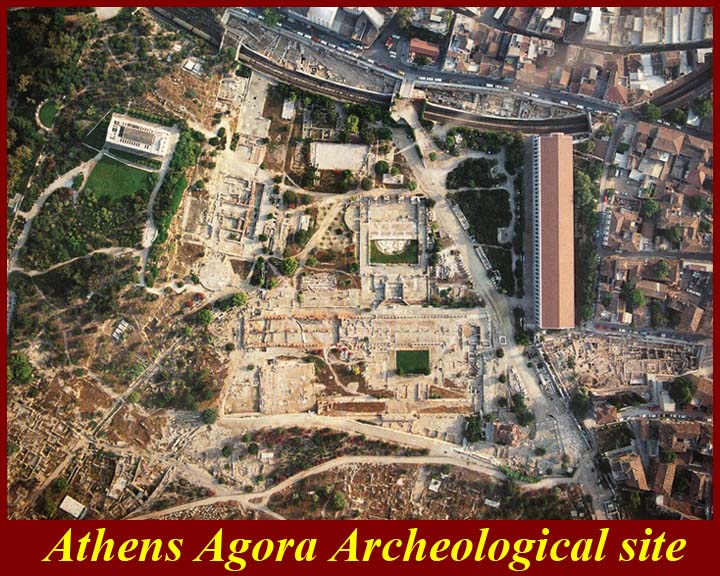

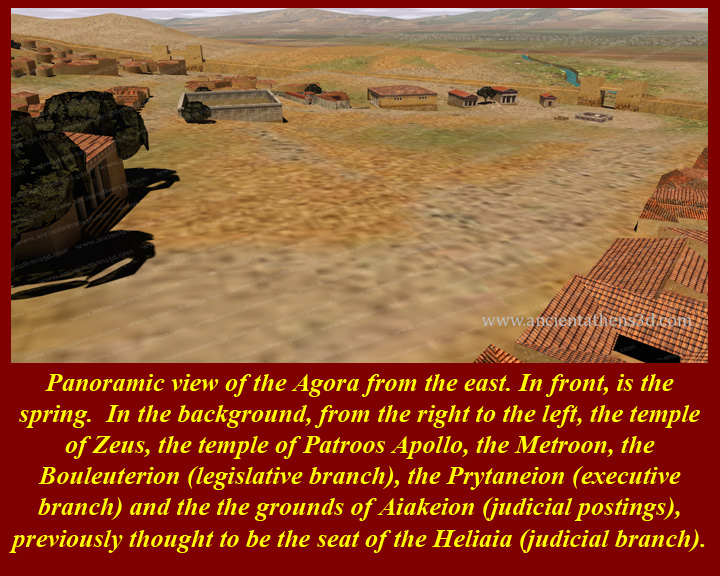

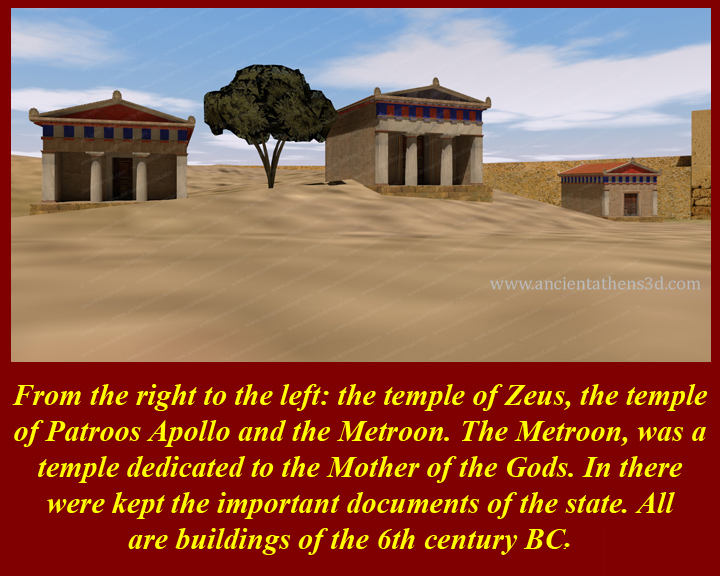

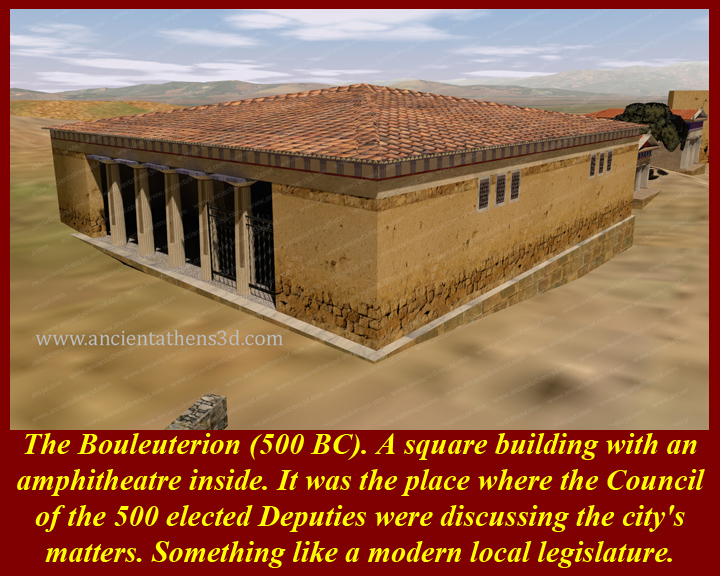

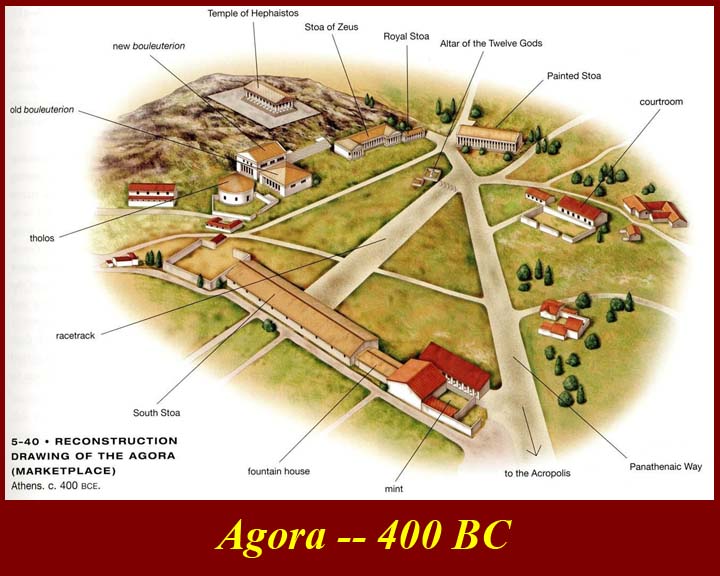

Agora

Read

about the development of the Athens Agora at http://www.ancient.eu/article/144/.

See also http://www.ancientathens3d.com/archaicagoraEn.htm

and http://ancient-greece.org/archaeology/agora.html

and http://ancient-greece.org/history/acropolis-archaic.html

And http://www.ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/excavationAgora.

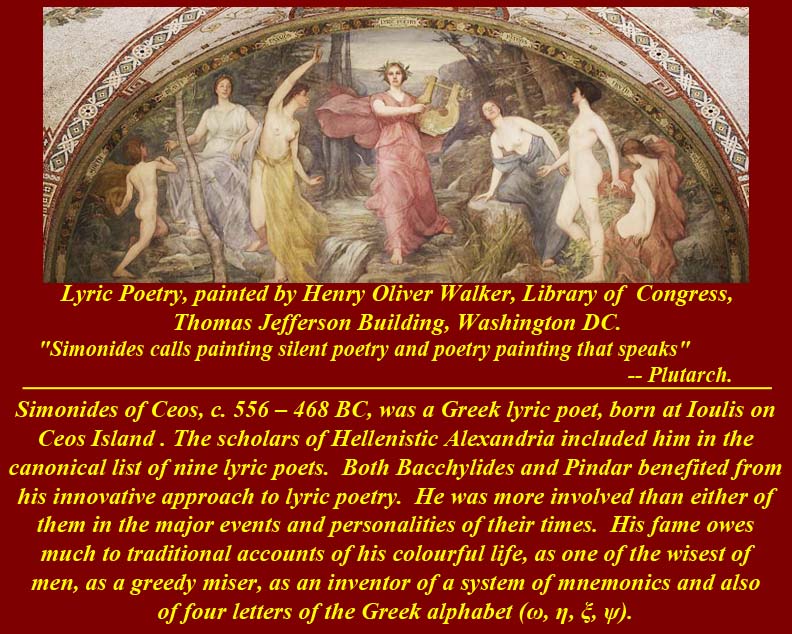

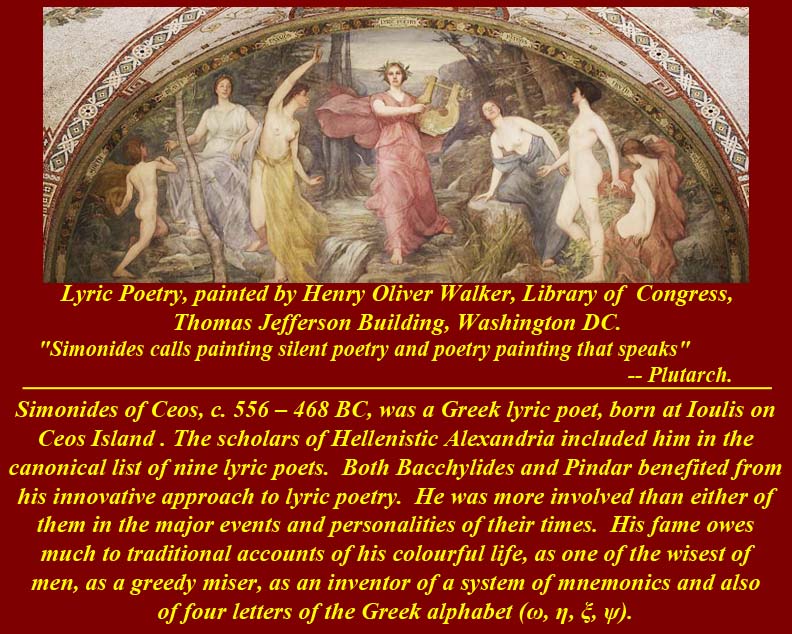

AtticCulture -- Lyric (Metic) Poetry

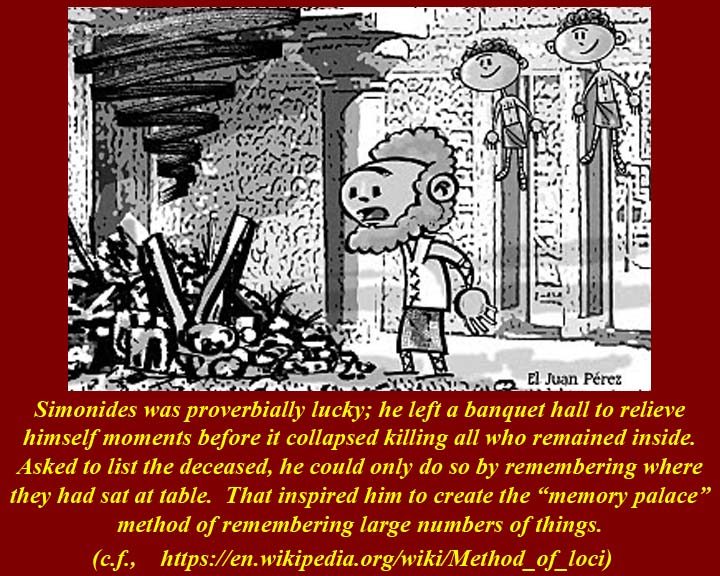

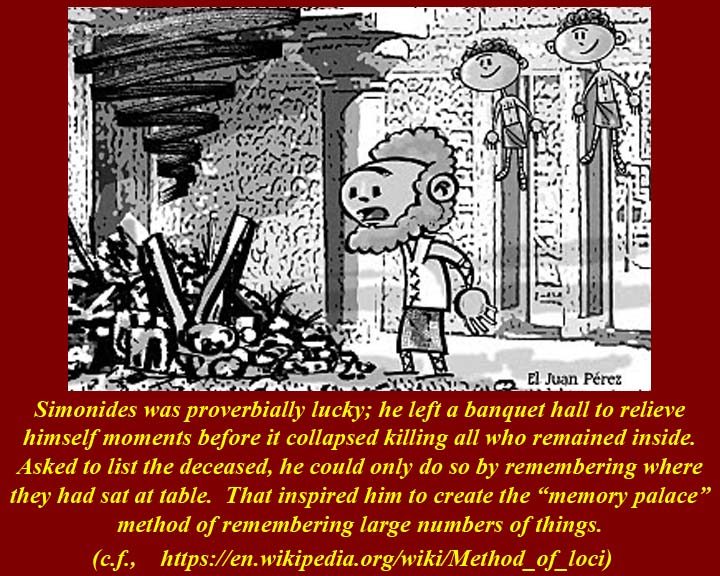

Simonides was an innovator among Archaic period Greek

lyric poets. A major member of the canonical "nine

lyric poets", he is considered to have been the

first to have composed poetry meant to be read rather

than received by listening. He also is credited

with having invented four letters in the revised Greek

alphabet (ω, η, ξ, ψ -- that is, omega, eta, ksi, and

psi) and with inventing a memory system ("memory

palace" or "method of loci"). He was born in

the Archaic period and lived into the Classical period

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simonides_of_Ceos

and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine_Lyric_Poets

and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palatine_Anthology

and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Method_of_loci.

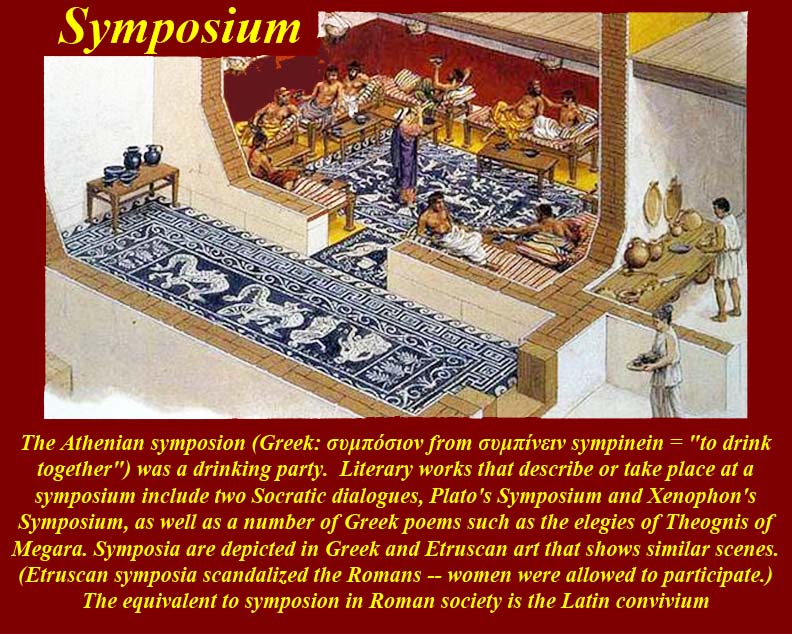

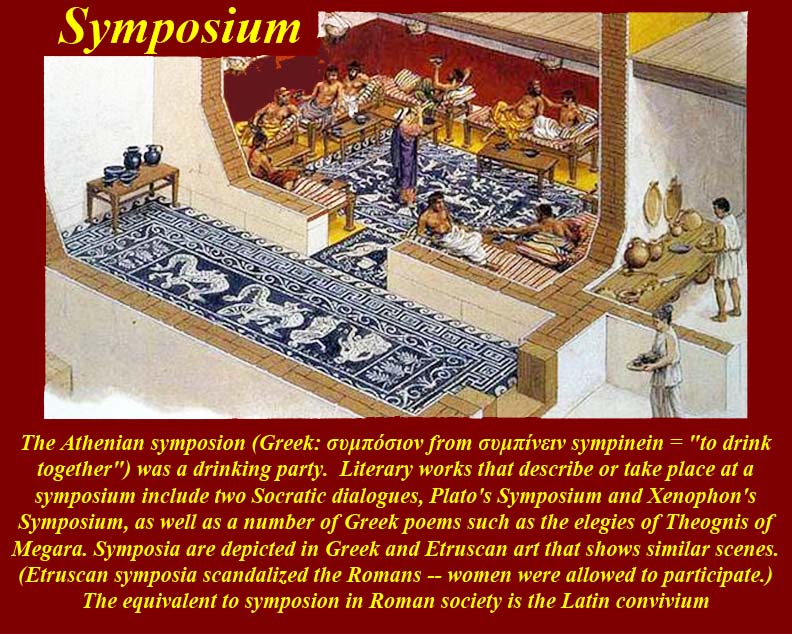

Symposia

The Greek symposion (Latin convivium)

was a key Hellenic social institution. It was a

forum for men of respected families to debate, plot,

boast, or simply to revel with others. They were

frequently held to celebrate the introduction of young

men into aristocratic society. Symposia were also

held by aristocrats to celebrate other special

occasions, such as victories in athletic and poetic

contests. ...

Symposia were usually held in the andrōn

(ἀνδρών), the men's quarters of the household. The

participants, or "symposiasts", would recline on

pillowed couches arrayed against the three walls of the

room away from the door. Due to space limitations the

couches would number between seven and nine, limiting

the total number of participants to somewhere between

fourteen and twenty seven. ...

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symposium

for a description of the Greek symposium

and, for Plato's Symposium in English, see http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/symposium.html.

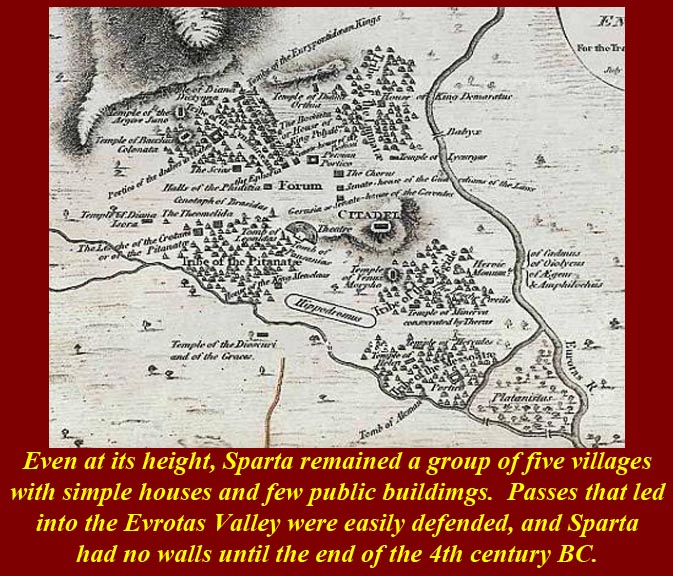

Sparta

Unlike Athens, which had a previously existing citadel

and town, Sparta always was a collection of four (later

five) Dorian villages in the easily defendable Eurotas

River valley. The valley had been inhabited by

earlier groups from as early as the Middle Neolithic,

but was not considered to be "Spartan" until the Dorians

took over the area in the latter part of the Dark Age

period. (The Dorians were either new immigrants or

were a formerly subjugated majority that took over

during the Dark Age.)

Archeologically, Sparta itself begins to show signs of

settlement only around 1000 BC, some 200 years after the

collapse of Mycenaean civilization Of the four

villages that initially made up the Spartan Polis,

historian George

Forrest suggests that the two closest to the

Acropolis were the originals, and the two more far flung

settlements were of later foundation. The dual kingship

may originate in the fusion of the first two

villages. One of the effects of the Mycenaean

collapse had been a sharp drop in population.

Following that, there was a significant recovery, and

this growth in population is likely to have been more

marked in Sparta, as it was situated in the most fertile

part of the plain.

Between the 8th and 7th centuries BC the Spartans

experienced a period of lawlessness and civil strife,

later testified by both Herodotus and Thucydides.

As a result, they carried out a series of political and

social reforms of their own society which they later

attributed to a semi-mythical lawgiver, Lycurgus.

These reforms mark the beginning of the history

oClassical Sparta.

For more on the history and development of Sparta, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Sparta

and http://www.ancient.eu/sparta/

and http://www.civilization.org.uk/greece-2/sparta.

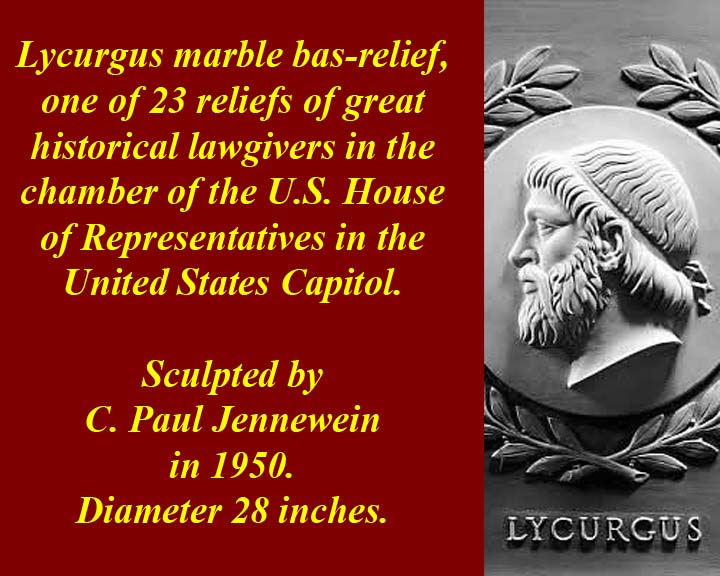

We don't know much about Lycurgus, even when or whether

he was alive or a real person. It's another

founding myth like the Theseus myth of the founding of

Athens. Spartans believed that he was their

organizer and lawgiver, a man who refused an offer of

kingship out of respect for law and justice.

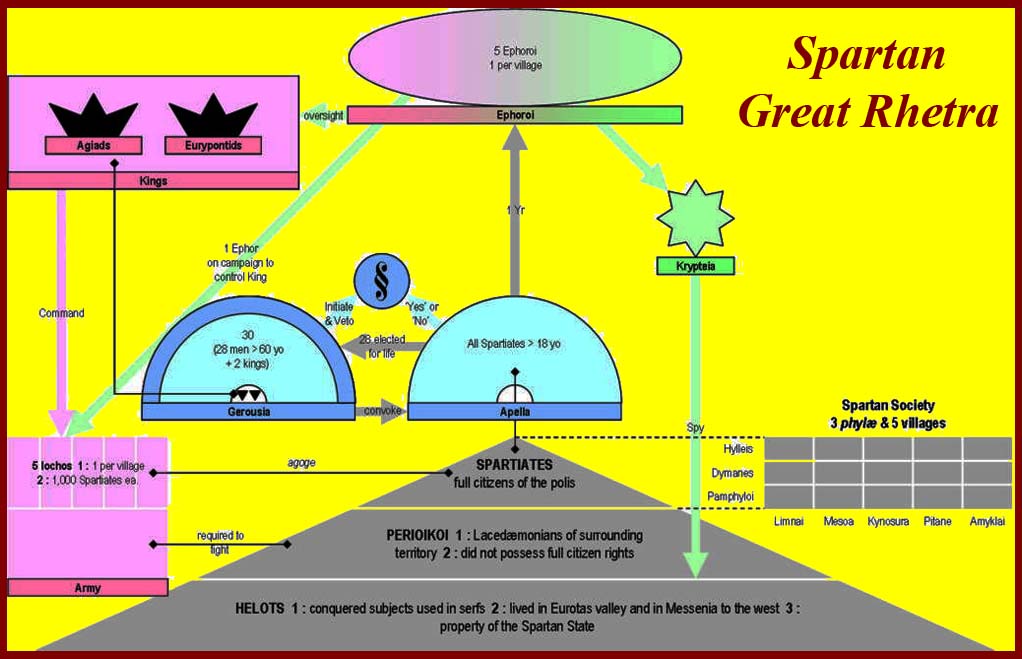

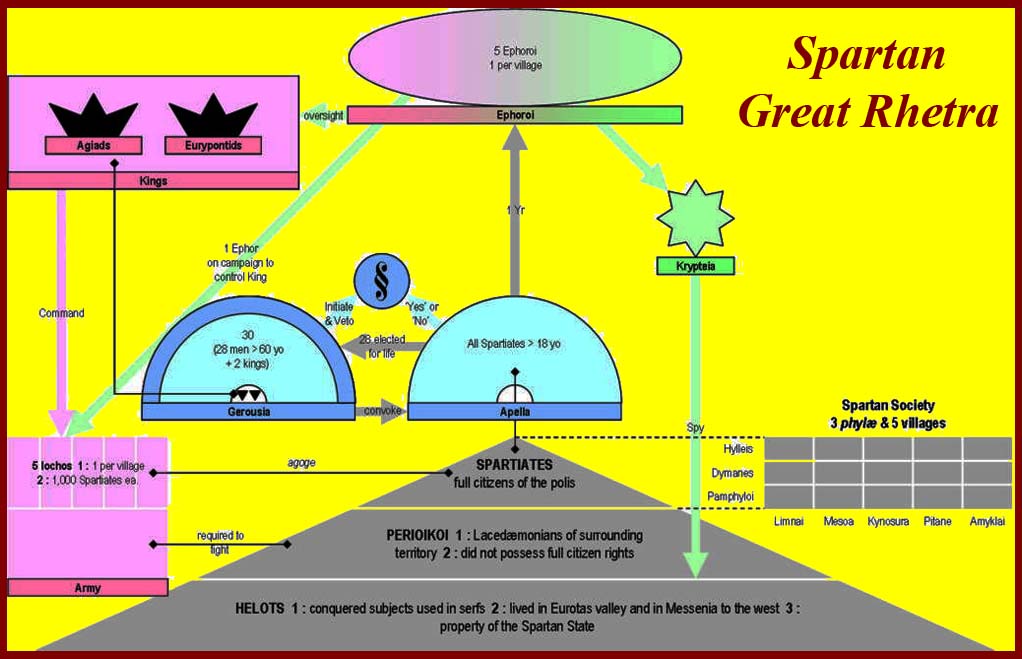

The myth includes the story of how Lycurgus, seeing the

disorder in early Sparta, sought advice from the Delphic

Sybil and received in reply the "Great Rhetra" as a

complete constitution for Sparta. Once again there

are inconsistencies and anachronisms which are glossed

by Herodotus but are , in fact, acknowledged by

Plutarch.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycurgus_of_Sparta

and http://www.mmdtkw.org/Gr0926SpartaGreatRhetra.jpg

and (Herodotus on Lycurgus) http://ancienthistory.about.com/library/bl/bl_text_herodotus_1.htm#65

and (Plutarch on Lycurgus -- lives) http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Lycurgus*.html

and (Plutarch on Lycurgus -- Moralia, Apophthegmata

Laconica ) http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Sayings_of_Spartans*/Lycurgus.html

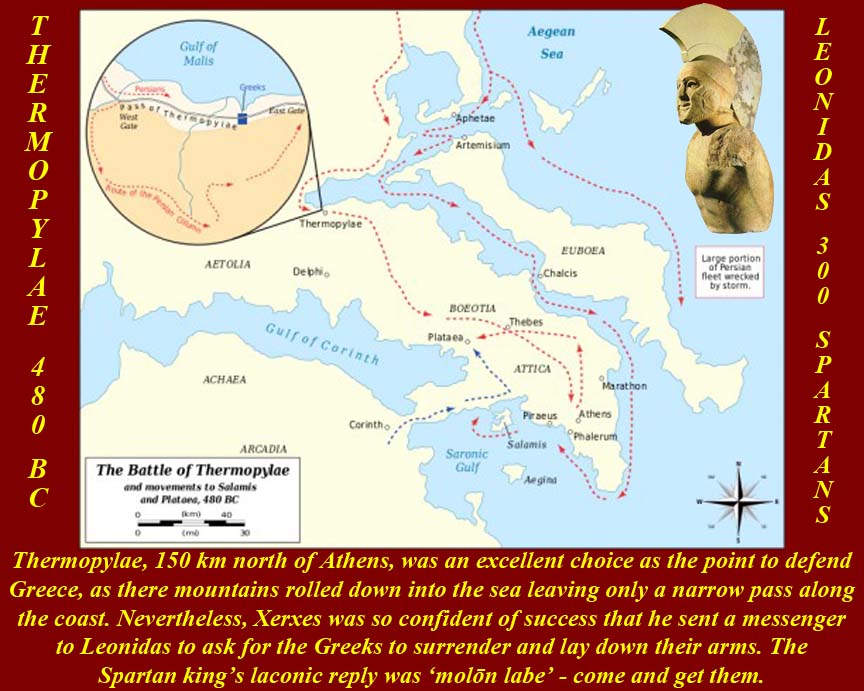

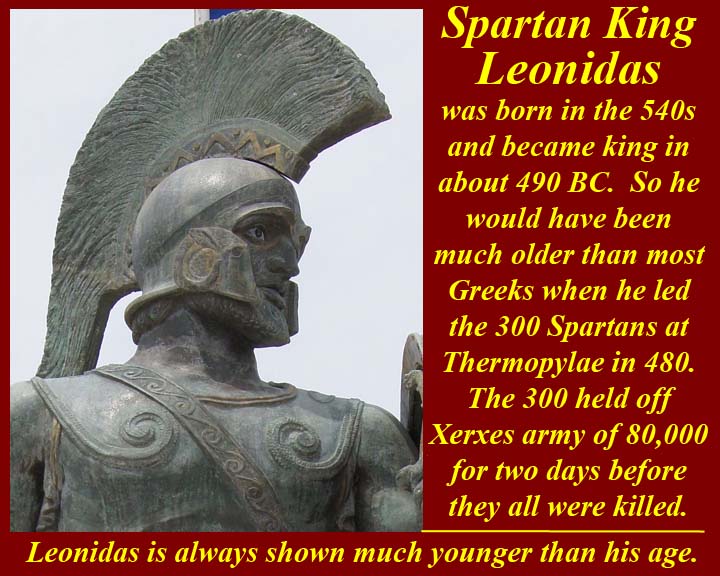

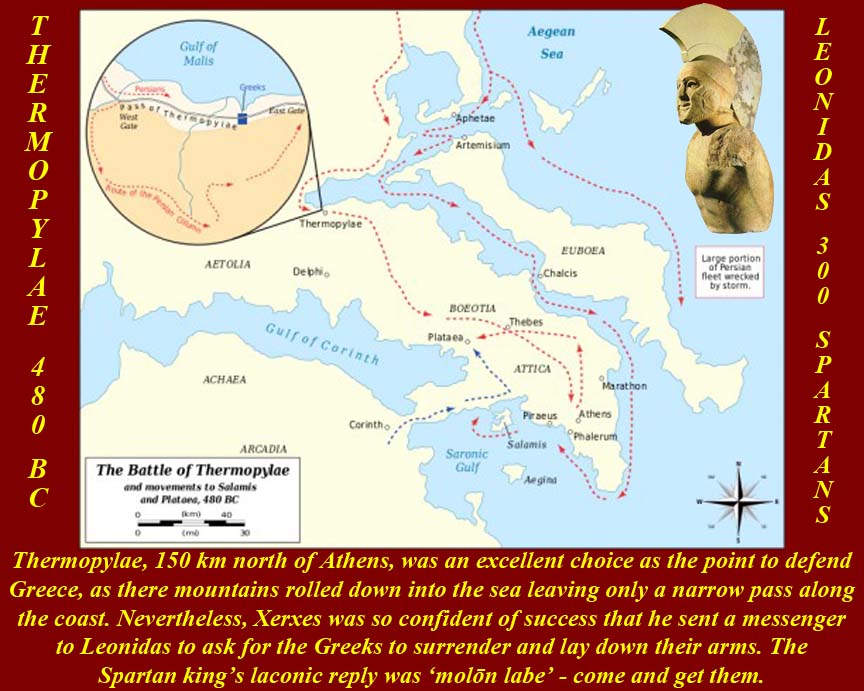

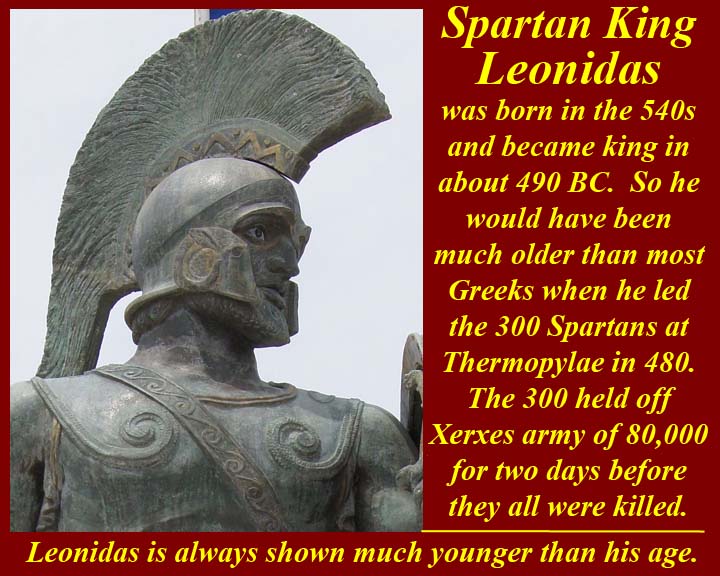

Leonidas

of Sparta was already an old man by ancient Greek

standards when he and three hundred Spartans held off

the 80,000 Persians under Xerxes at Thermopylae in 480

BC. (The Spartans could have been said to have

taught the Persians what the name of the place really

meant; "the hot gates of Hell"). The battle

delayed the Persians long enough to allow the Athenians

and their fleet to retreat to Salamis Island where the

destruction of the Persian fleet caused Xerxes to

retreat from Greece never to return. All of this

will be covered in the next unit (and see

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Thermopylae

if you can't wait for next week.)

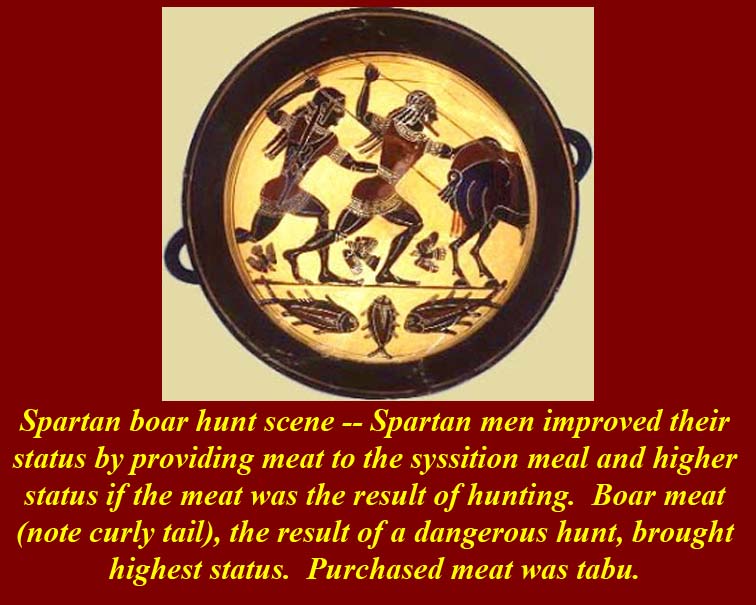

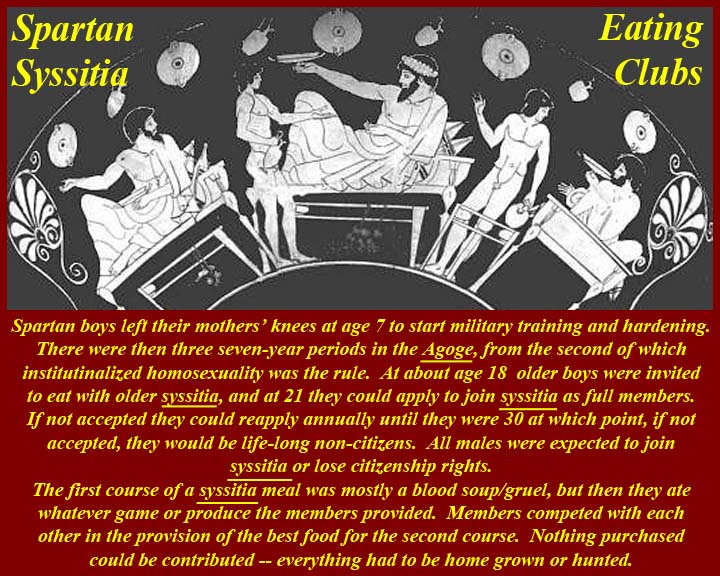

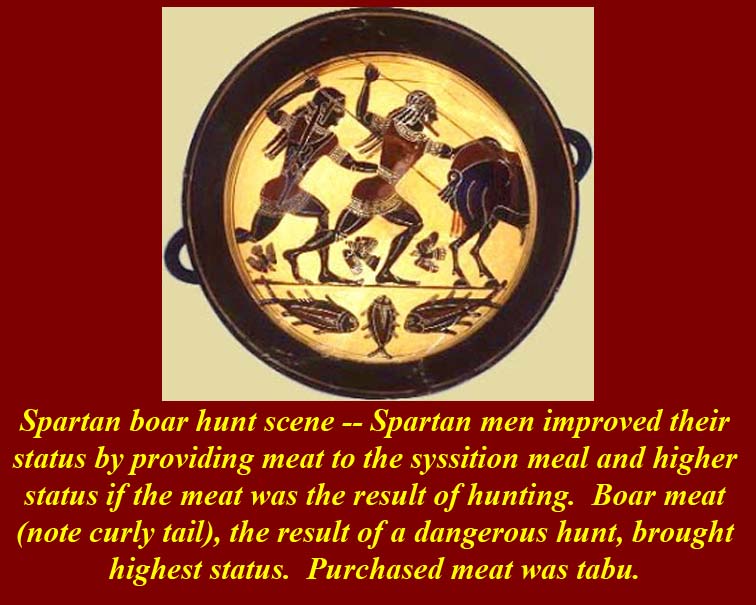

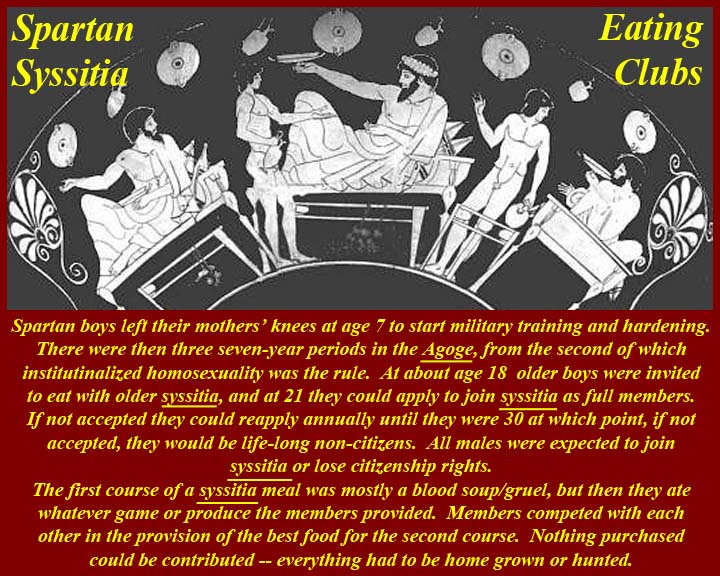

Syssition/Syssitia -- There is a

great deal of discussion of how the singular (syssition)

and plural (syssitia) forms of the word should be

used and whether they refer to the eating groups or to

the meals the groups ate together. Even the

ancient Greeks apparently couldn't decide.

Whichever form is used, this is what happened; Syssition/Syssitia was/were

the culmination of the coming-of-age process

called agoge.

The agōgē (Greek: ἀγωγή in Attic Greek, or

ἀγωγά, agōgá in Doric Greek) was the rigorous

education and training regimen mandated for all

male Spartan citizens, except for the firstborn

son in the ruling houses, Eurypontid and Agiad.

The training involved learning stealth,

cultivating loyalty to the Spartan group,

military training (e.g. pain tolerance),

hunting, dancing, singing and social

(communicating) preparation.[1] The word "agoge"

meant in ancient Greek, rearing, but in this

context generally meant leading, guidance or

training.[2]

According to folklore, agoge was introduced by

the semi-mythical Spartan law-giver Lycurgus but

its origins are thought to be between the 7th

and 6th centuries BC[3][4] when the state

trained male citizens from the ages of seven to

twenty-one.[1][5]

The aim of the system was to produce physically

and morally strong males to serve in the Spartan

army. It encouraged conformity and the

importance of the Spartan state over one's

personal interest and generated the future

elites of Sparta. The men would become the

"walls of Sparta" because Sparta was the only

Greek city with no defensive walls after they

had been demolished at the order of Lycurgus.

Discipline was strict and the males were

encouraged to fight amongst themselves to

determine the strongest member of the group.

From about age 14, boys were taken into

homosexual pairing with older males.

At age 21 a young man who had completed agoge

would apply to join a syssitiongroup of adult

males who would eat all their evening meals

together and sleep in their barracks.

More information is available at the Internet

sites listed immediately below.

For more on Syssitia, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syssitia

For the Syssytia diet, see http://thespartandiet.blogspot.com/2010/10/inside-spartan-syssition.html

For Agoge, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agoge

For Spartan maturity processes, see:

(Male) http://www.labrys.gr/index-en.php?l=catalysing_maturity-en#8

and (Female) http://www.labrys.gr/index-en.php?l=catalysing_maturity-en#11.

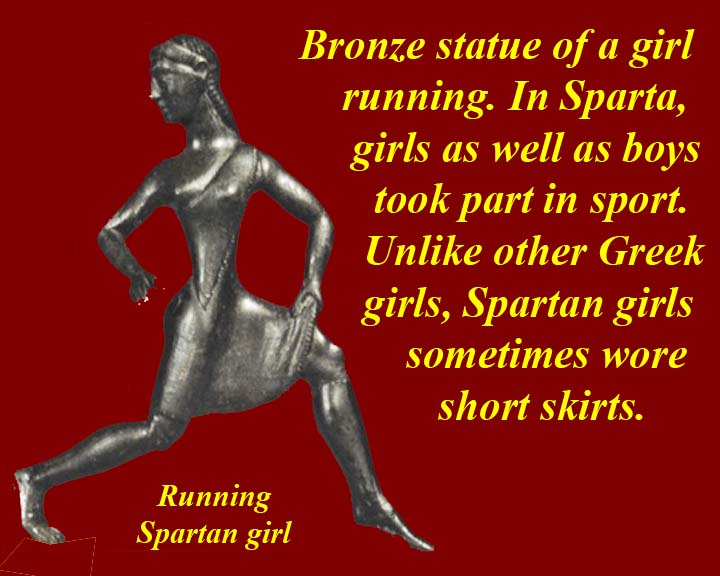

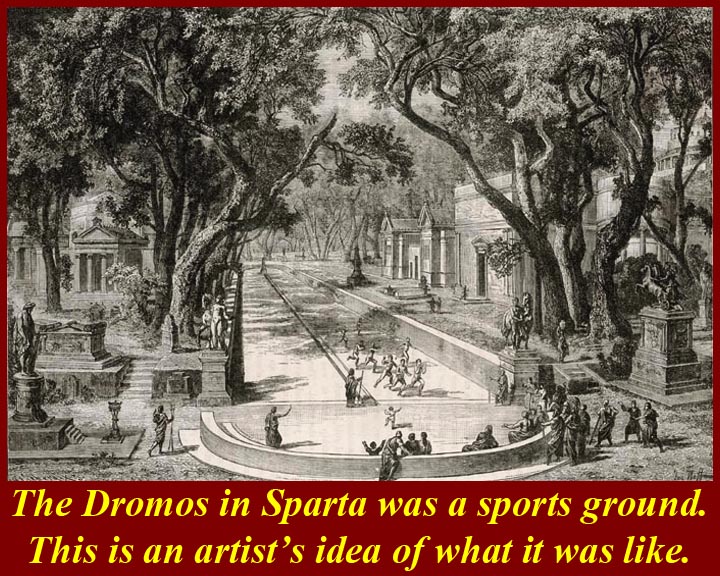

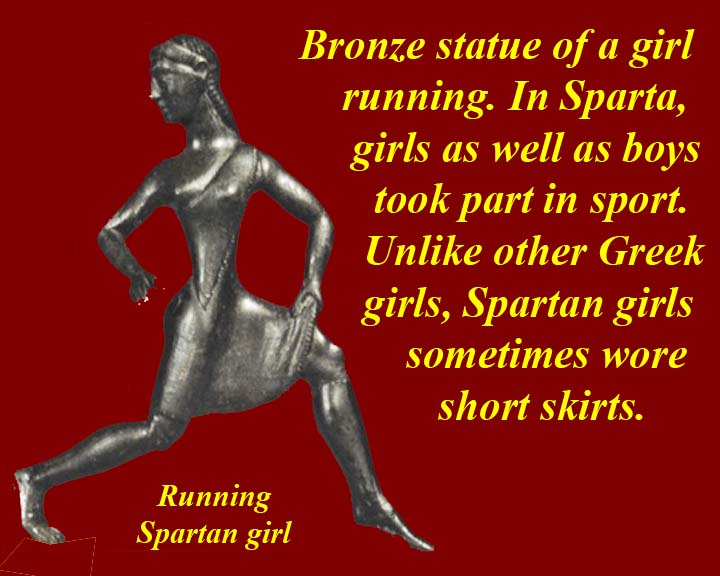

Training and competition in running were integral

parts of the upbringing of all Spartans, male and

female. Everyone was expected to be completely

physically fit with the males ready for battle and

females ready for child bearing (as soon a they were

physically mature -- starting in their early their

teen years.)

See http://www.sikyon.com/sparta/agogi_eg.html

and https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/xeno-sparta1.asp

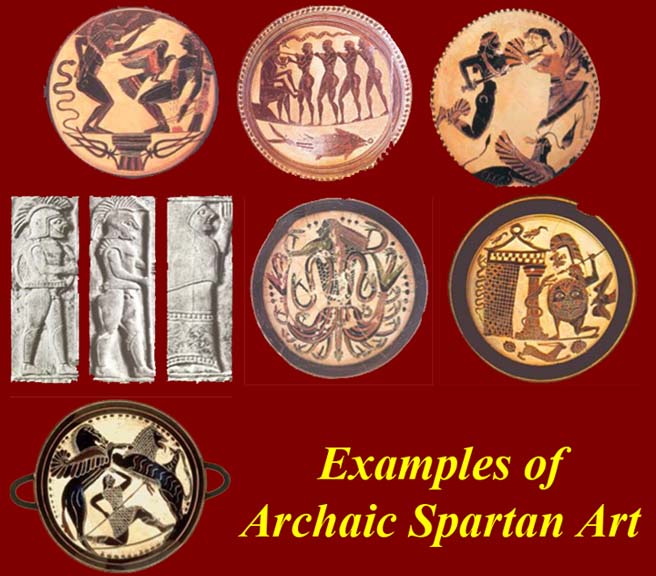

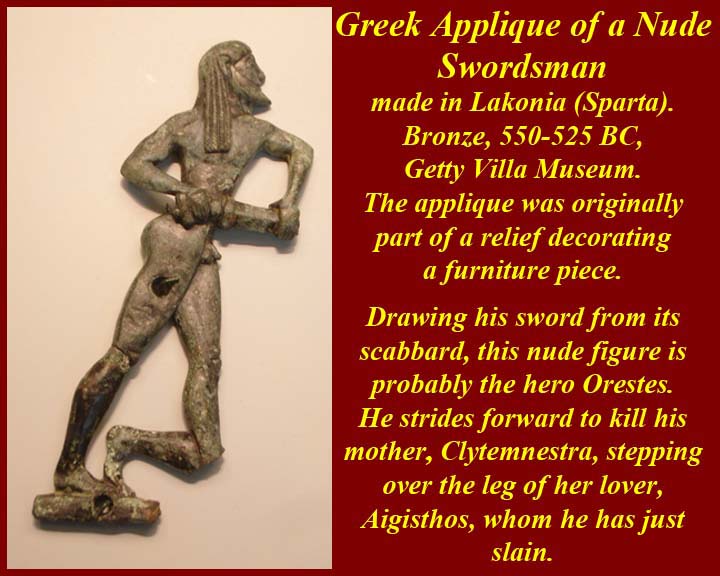

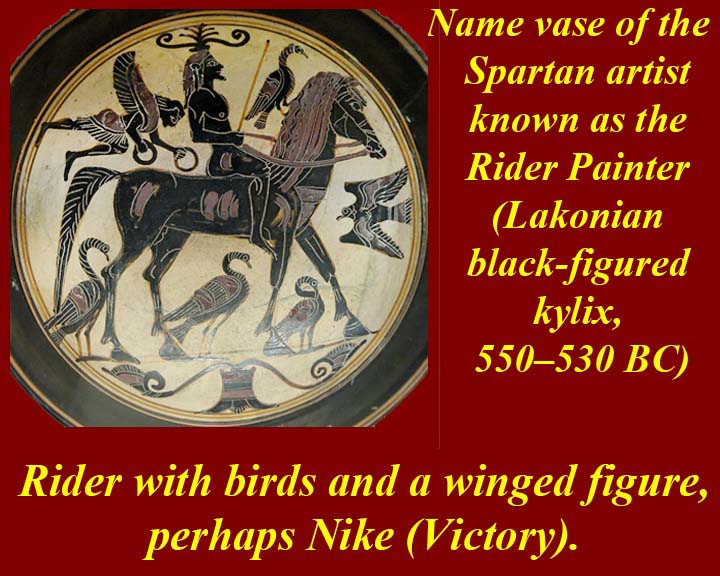

Bronze

furniture relief

Bronze

furniture relief  Painted horseman kylix (drinking bowl)

Painted horseman kylix (drinking bowl)

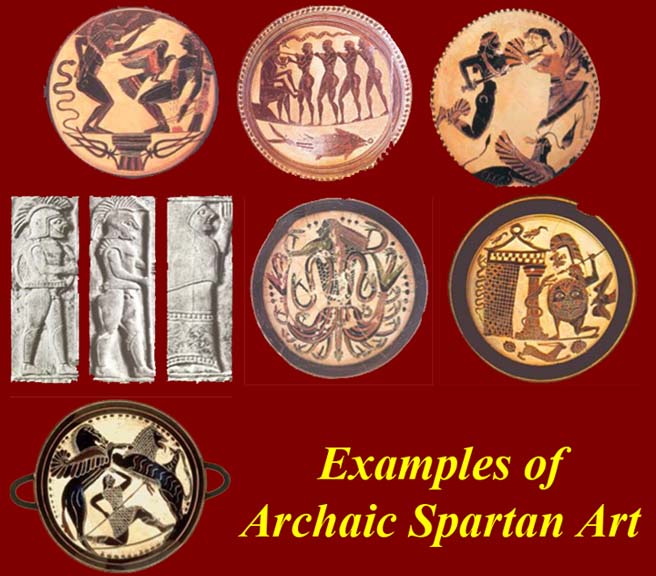

Spartan detailed bronze artwork is

characteristically on a martial or training pattern as

is the figure from the bottom of a kylix showing a

victorious horseman.

See http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/spar/hd_spar.htm

There is a great deal of controversy surrounding the question of why Greek communities became poleis. Some historians and political analysts found it inevitable. Aristotle, in fact, claimed that the polis was the natural situation for mankind. He defined humans as "beings who by nature live in a polis" (Politics 1253a2-3). However, the polis was a unique Greek invention and far from inevitable. The specific geography and history of Greece allowed its conception.

Bronze furniture relief

Painted horseman kylix (drinking bowl)