This page is on the internet at http://www.mmdtkw.org/GR--Unit16-PelopononnesianWar-Readings.html

Readings for Ancient Greece 2 -- Unit 16, PeloponnesianWar

[Text in colored letters are Internet links; click on links to go to additional information. Use your web browser "back" or "return" link to come back to this page.]

Contents:

1 Peloponnesian Wars (Wikipedia)

1a First Pelopponesian War -- 460-445 BC (Wikipedia)

1b Second (resumed) Pelopponesian War -- 432-404 BC (Wikipedia)

2 Peloponnesian War (livius.org)

3 Links to full English text Thucydides The History of the Peloponnesian War

(Crawley Translation, 1874)

AudioBook: Thucydides' The History of the Peloponnesian War (Crawley

Translation).

4 A 53 minute TV documentary on the Pelopponesian War.

5 Corinthian War Postscript (Wikipedia)

1 Peloponnesian Wars

1a First Peloponnesian War

For the Second (resumed) Peloponnesian War beginning in 431 BC, see Peloponnesian War or below.

First Peloponnesian War

Date 460–445 BC Location Mainland Greece Result Arrangement between Sparta and Athens ratified by the "Thirty Years' Peace" Territorial

changesMegara was returned to the Peloponnesian League, Troezen and Achaea became independent, Aegina was to be a tributary to Athens but autonomous, and disputes were to be settled by arbitration. Belligerents Delian League led by Athens,

ArgosPeloponnesian League led by Sparta,

ThebesCommanders and leaders Pericles

Cimon

Leocrates

Tolmides

Myronides

CarniusPleistoanax

NicodemesThe First Peloponnesian War (460–445 BC) was fought between Sparta as the leaders of the Peloponnesian League and Sparta's other allies, most notably Thebes, and the Delian League led by Athens with support from Argos. This war consisted of a series of conflicts and minor wars, such as the Second Sacred War. There were several causes for the war including the building of the Athenian long walls, Megara's defection and the envy and concern felt by Sparta at the growth of the Athenian Empire.

The war began in 460 BC (Battle of Oenoe).[1][2][3][4] At first the Athenians had the better of the fighting, winning the naval engagements using their superior fleet. They also had the better of the fighting on land, until 457 BC when the Spartans and their allies defeated the Athenian army at Tanagra. The Athenians, however, counterattacked and scored a crushing victory over the Boeotians at the Battle of Oenophyta and followed this victory up by conquering all of Boeotia except for Thebes.

Athens further consolidated their position by making Aegina a member of the Delian League and by ravaging the Peloponnese. The Athenians were defeated in 454 BC by the Macedonians which caused them to enter into a five years' truce with Sparta. However, the war flared up again in 448 BC with the start of the Second Sacred War. In 446 BC, Boeotia revolted and defeated the Athenians at Coronea and regained their independence.

The First Peloponnesian War ended in an arrangement between Sparta and Athens, which was ratified by the Thirty Years' Peace (winter of 446–445 BC). According to the provisions of this peace treaty, both sides maintained the main parts of their empires. Athens continued its domination of the sea while Sparta dominated the land. Megara returned to the Peloponnesian League and Aegina becoming a tribute paying but autonomous member of the Delian League. The war between the two leagues restarted in 431 BC and in 404 BC, Athens was occupied by Sparta.

Contents

Origins and causes

A map of the Delian League.A mere twenty years before the First Peloponnesian War broke out, Athens and Spartans had fought alongside each other in the Greco-Persian Wars. In that war, Sparta had held the hegemony of what modern scholars call the Hellenic League and the overall command in the crucial victories of 480 and 479 BC. Over the next several years, however, Spartan leadership bred resentment among the Greek naval powers that took the lead in carrying the war against Persian territories in Asia and the Aegean, and after 478 BC the Spartans abandoned their leadership of this campaign.[5] Sparta grew wary of Athen's strength after they had fought alongside each other to disperse the Persian from their lands. When Athens started to rebuild its walls and the strength of its naval power Sparta and its allies began to fear that Athens was becoming too powerful.[6] Different policies made it difficult for Athens and Sparta to avoid going to war, since Athens wanted to expand its territory and Sparta wanted to dismantle Athens's democratic regime.[7]

Athens, meanwhile, had been asserting itself on the international scene, and was eager to take the lead in the Aegean. The Athenians had already rebuilt their walls, against the express wishes of Sparta,[8] and in 479 BC and 478 BC had taken a much more active role in the Aegean campaigning. In the winter of 479–8 BC they accepted the leadership of a new league, the Delian League, in a conference of Ionian and Aegean states at Delos. The Athenians rebuilt their walls in secret at the urging of Themistocles, who convinced the Athenians that this was the best way to protect themselves. Themistocles also delayed talks with Sparta for universal arms control by constantly finding issues with Sparta's proposals, stating that it would leave Athens vulnerable to Sparta's superior hoplites and superior fighting formation: the phalanx.[9] After the completion of the walls Themistocles declared Athens independent of Spartan hegemony stating that Athens knew what was in its best interest and was now strong enough to defend itself.[10] At this time, one of the first hints of animosity between Athens and Sparta emerges in an anecdote reported by Diodorus Siculus, who said that the Spartans in 475–474 BC considered reclaiming the hegemony of the campaign against Persia by force;[11] Modern scholars, although uncertain of the dating and reliability of this story, have generally cited it as evidence of the existence, even at this early date, of a "war party" in Sparta.[12][13]

The Athenian long walls which connected Athens to Piraeus.For some time, however, friendly relations prevailed between Athens and Sparta. Themistocles, the Athenian of the period most associated with an anti-Spartan policy, was ostracised at some point in the early 470s BC, and was later forced to flee to Persia.[14] In his place in Athens rose Cimon, who advocated a policy of cooperation between the two states. Cimon was Athens' proxenos at Sparta, and so fond was he of that city that he named one of his sons Lakedaemonios, meaning "Spartan".[15] Still, hints of conflict emerged. Thucydides reports that in the mid 460s BC, Sparta actually decided to invade Attica during the Thasian rebellion, and was only prevented from doing so by an earthquake, which triggered a revolt among the helots.[16] Perhaps it was this revolt that prevented Sparta from attacking Athens before the Athenian walls were completed even though with Sparta's superior hoplites and fighting techniques it could have easily conquered Athens.[17]

It was that helot revolt which would eventually bring on the crisis that precipitated the war. Unable to quell the revolt themselves, the Spartans summoned all their allies to assist them, invoking the old Hellenic League ties. Athens responded to the call, sending out 4,000 men with Cimon at their head.[18][19] However, something either in the behavior or appearance of the Athenian force insulted the Spartans and they dismissed the Athenians, alone of all their allies.[20] This action destroyed the political credibility of Cimon; he had already been under assault by opponents at Athens led by Ephialtes, and shortly after this embarrassment he was ostracized. The demonstration of Spartan hostility was unmistakable, and when Athens responded, events spiraled rapidly into war. Athens concluded several alliances in quick succession: one with Thessaly, a powerful state in the north; one with Argos, Sparta's traditional enemy for centuries; and one with Megara, a former ally of Sparta's which was faring badly in a border war with Sparta's more powerful ally Corinth. At about the same time, Athens settled the helots exiled after the defeat of their revolt at Naupactus on the Corinthian Gulf. By 460 BC, Athens found itself openly at war with Corinth and several other Peloponnesian states, and a larger war was clearly imminent.

Early battles

As this war was the beginning, Athens also took on a serious military commitment in another part of the Aegean when they sent a force to assist Inarus, a Libyan king who had led almost all of Egypt in revolt from the Persian king Artaxerxes. Athens and her allies sent a fleet of 200 ships to assist Inarus — a substantial investment of resources.[21] Thus, Athens entered the war with her forces spread across several theaters of conflict.

In either 460 or 459 BC, Athens fought several major battles with the combined forces of several Peloponnesian states. On land, the Athenians were defeated by the armies of Corinth and Epidaurus at Halieis, but at sea they were victorious at Cecryphaleia (a small island between Aegina and the coast of Epidaurus).[22] Alarmed by this Athenian aggressiveness in the Saronic Gulf, Aegina entered into the war against Athens, combining its powerful fleet with that of the Peloponnesian allies.[23] In the resulting sea battle, the Athenians won a commanding victory, capturing seventy Aeginetan and Peloponnesian ships. They then landed at Aegina and led by Leocrates laid siege to the city.[22]

With substantial Athenian detachments tied down in Egypt and Aegina, Corinth invaded the Megarid, attempting to force the Athenians to withdraw their forces from Aegina to meet this new threat.[24] Instead, the Athenians scraped together a force of men too old and boys too young for ordinary military service and sent this force, under the command of Myronides, to relieve Megara. The resulting battle was indecisive, but the Athenians held the field at the end of the day and were thus able to set up a trophy of victory. About twelve days later the Corinthians attempted to return to the site to set up a trophy of their own, but the Athenians issued forth from Megara and routed them; during the retreat after the battle a large section of the Corinthian army blundered into a ditch-ringed enclosure on a farm, where they were trapped and massacred.

A Greek hoplite made up the majority of the soldiers in a state's army.For several years at the beginning of the war, Sparta remained largely inert. Spartan troops may have been involved in some of the early battles of the war, but if so they were not specifically mentioned in any sources.[25] In 458 BC or 457 BC,[26] Sparta at last made a move, but not directly at Athens. A war had broken out between Athens' ally Phocis and Doris, across the Corinthian Gulf from the Peloponnese.[27] Doris was traditionally identified as the homeland of the Dorians, and the Spartans, being Dorians, had a longstanding alliance with that state. Accordingly, a Spartan army under the command of the general Nicomedes, acting as deputy for the underage king Pleistonax, was dispatched across the Corinthian Gulf to assist. This army forced the Phocians to accept terms, but while it was in Doris an Athenian fleet moved into position to block its return across the Corinthian Gulf.

At this point Nicomedes led his army south into Bœotia. Several factors may have influenced his decision to make this move. First, secret negotiations had been underway with a party at Athens which was willing to betray the city to the Spartans in order to overthrow the democracy. Furthermore, Donald Kagan has suggested that Nicomedes had been in contact with the government of Thebes and planned to unify Boeotia under Theban leadership; which, upon his arrival, he seems to have done.[28][29]

With a strong Spartan army in Boeotia and the threat of treason in the air, the Athenians marched out with as many troops, both Athenian and allied, as they could muster to challenge the Peloponnesians. The two armies met at the Battle of Tanagra. Before the battle, the exiled Athenian politician Cimon, armored for battle, approached the Athenian lines to offer his services, but was ordered to depart; before going, he ordered his friends to prove their loyalty through their bravery.[30] This they did, but the Athenians were defeated in the battle, although both sides suffered heavy losses. The Spartans, rather than invading Attica, marched home across the isthmus, and Donald Kagan believes that at this point Cimon was recalled from exile and negotiated a four-month truce between the sides; other scholars believe no such truce was concluded, and place Cimon's return from exile at a later date.[31] Athenian success can also be contributed to them making an alliance with Argos, Sparta's enemy and only threat for control over the Peloponnesian league. The alliance between Athens and Argos was moreover seen as defensive measure to counteract Sparta's strength in the military.[32]

Athens conquers

A Greek trireme, the main type of ships used by the Greek states.The Athenians rebounded well after their defeat at Tanagra, by sending an army under Myronides to attack Boeotia.[33] The Boeotian army gave battle to the Athenians at Oenophyta.[33] The Athenians scored a crushing victory which led to the Athenians conquering all of Boeotia except for Thebes, as well as Phocis and Locris.[33] The Athenians pulled down Tanagra's fortifications and took the hundred richest citizens of Locris and made them hostages.[33] The Athenians also took this chance to finish off the construction of their long walls.[33]

Shortly after this, Aegina surrendered and was forced to pull down its walls, surrender its fleet and became a tribute-paying member of the Delian League, completing what Donald Kagan has called an annus mirabilis for the Athenians.[34]

The Athenians, pleased by their success, sent an expedition under the general Tolmides to ravage the coast of the Peloponnese.[33] The Athenians circumnavigated the Peloponnese and attacked and sacked the Spartan dockyards, whose location was most probably Gythium.[33] The Athenians followed up this success by capturing the city of Chalcis on the Corinthian Gulf and then landing in the territory of Sicyon and defeating the Sicyonians in battle.[33]

The importance of Megara

Modern scholars have emphasized the critical significance of Athenian control of Megara in enabling the early Athenian successes in the war. Megara provided a convenient port on the Corinthian gulf, to which Athenian rowers could be transported overland, and a significant number of ships were probably kept at Megara's port of Pagae throughout the war.[35] Moreover, while early modern scholars were skeptical of Athens's ability to prevent a Spartan army from moving through the Megarid, recent scholarship has concluded that the pass of Geraneia could have been held by a relatively small force;[36] thus, with the isthmus of Corinth closed and Athenian fleets in both the Corinthian and Saronic gulfs, Attica was unassailable from the Peloponnese. The Spartans' inability to attack Megara proved to be a key component in their loss to Athenians, but one scholar believes that the Spartans' inability to attack and control Megara was due to poor calculations and Athenian efforts to avoid an open land battle with the Spartans.[37]

Athenian crisis and the truce

Athens' remarkable string of successes came to a sudden halt in 454 BC, when its Egyptian expedition was finally crushingly defeated. A massive Persian army under Megabazus had been sent overland against the rebels in Egypt some time earlier, and upon its arrival had quickly routed the rebel forces. The Greek contingent had been besieged on the island of Prosopitis in the Nile. In 454, after a siege of 18 months, the Persians captured the island, destroying the force almost entirely. Though the force thus obliterated was probably not as large as the 200 ships that had originally been sent, it was at least 40 ships with their full complements, a significant number of men.[38]

The disaster in Egypt severely shook Athens' control of the Aegean, and for some years afterwards the Athenians concentrated their attention on reorganizing the Delian League and stabilizing the region.[39] The Athenians responded to a call for assistance from Orestes, the son of Echecratides, King of Thessaly, to restore him after he was exiled. Together with their Boeotian and Phocian allies, the Athenians marched to Pharsalus. They were not able to achieve their goals because of the Thessalian cavalry and were forced to return to Athens not having restored Orestes or capturing Pharsalus.

In 451 BC, therefore, when Cimon returned to the city, his ostracism over, the Athenians were willing to have him negotiate a truce with Sparta.[40] Cimon arranged a five-year truce,[41] and over the next several years Athens concentrated its efforts in the Aegean.

After the truce

The years after the truce were eventful ones in Greek politics. The Peace of Callias, if it existed, was concluded in 449 BC; it was probably in that same year that Pericles passed the Congress decree, calling for a pan-Hellenic congress to discuss the future of Greece.[42] Modern scholars have debated extensively over the intent of that proposal; some regard it as a good faith effort to secure a lasting peace, while others view it as a propaganda tool.[43] In any event, Sparta derailed the Congress by refusing to attend.[44]

In the same year the Second Sacred War erupted, when Sparta detached Delphi from Phocis and rendered it independent. In 448 BC, Pericles led the Athenian army against Delphi, in order to reinstate Phocis in its former sovereign rights on the oracle of Delphi.[45][46]

In 446 BC a revolt broke out in Boeotia which was to spell the end of Athens's "continental empire" on the Greek mainland.[47] Tolmides led an army out to challenge the Bœotians, but after some early successes was defeated at the Battle of Coronea; in the wake of this defeat, Pericles imposed a more moderate stance and Athens abandoned Boeotia, Phocis, and Locris.[48]

The defeat at Coronea, however, triggered a more dangerous disturbance, in which Euboea and Megara revolted. Pericles crossed over to Euboea with his troops to quash the rebellion there, but was forced to return when the Spartan army invaded Attica. Through negotiation and possibly bribery,[49][50] Pericles persuaded the Spartan king Pleistoanax to lead his army home;[51] back in Sparta, Pleistoanax would later be prosecuted for failing to press his advantage, and fined so heavily that he was forced to flee into exile, unable to pay.[52] With the Spartan threat removed, Pericles crossed back to Euboea with 50 ships and 5,000 soldiers, cracking down any opposition. He then inflicted a stringent punishment on the landowners of Chalcis, who lost their properties. The residents of Istiaia, who had butchered the crew of an Athenian trireme, were chastised more harshly, since they were uprooted and replaced by 2,000 Athenian settlers.[51] The arrangement between Sparta and Athens was ratified by the "Thirty Years' Peace" (winter of 446–445 BC). According to this treaty, Megara was returned to the Peloponnesian League, Troezen and Achaea became independent, Aegina was to be a tributary to Athens but autonomous, and disputes were to be settled by arbitration. Each party agreed to respect the alliances of the other.[47]

Significance and aftermath

The middle years of the First Peloponnesian War marked the peak of Athenian power. Holding Boeotia and Megara on land and dominating the sea with its fleet, the city had stood utterly secure from attack.[53] The events of 447 and 446, however, destroyed this position, and although not all Athenians gave up their dreams of unipolar control of the Greek world, the peace treaty that ended the war laid out the framework for a bipolar Greece.[54] In return for abandoning her continental territories, Athens received recognition of her alliance by Sparta.[55] The peace concluded in 445, however, would last for less than half of its intended 30 years; in 431 BC, Athens and Sparta would go to war once again in the (second) Peloponnesian War, with decidedly more conclusive results.

Notes

- Pausanias, ., & Frazer, J. G. (1898). Pausanias's Description of Greece. London: Macmillan. Page 138

- E. D. Francis and Michael Vickers, Oenoe Painting in the Stoa Poikile, and Herodotus' Account of Marathon. The Annual of the British School at Athens Vol. 80, (1985), pp. 99-113

- In 460 BC, Argos rises against Sparta. Athens supports Argos and Thessaly. The small force that is sent by Sparta to quell the uprising in Argos is defeated by a joint Athenian and Argos force at Oenoe.

- Thucydides, ., & In Jowett, B. (1900). Thucydides. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pg 107 - 109

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.95.

- Karl Walling, "Thucydides On Policy, Strategy, And War termination," Naval War College Review Vol. 66 (autumn 2013): 49-50.

- Karl Walling, "Thucydides On Policy, Strategy, And War termination," Naval War College Review Vol. 66 (autumn 2013): 49

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.89–93.

- Karl Walling, "Thucydides On Policy, Strategy, And War termination," Naval War College Review Vol. 66 (autumn 2013):51-52.

- Karl Walling, "Thucydides On Policy, Strategy, And War termination," Naval War College Review Vol. 66 (autumn 2013): 52.

- Diodorus Siculus, Library 11.50.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 51–2.

- de Ste. Croix, Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 171–2.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 53–5.

- de Ste Croix, Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 172.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.101

- A.J. Holladay "Sparta's Role in The First Peloponnesian War", The Journal of The Hellenic Studies Vol. 97. (1977): 60.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 73–82.

- de Ste. Croix, Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 180–3.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.102.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.104.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.105.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 84.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.105–6.

- de Ste. Croix, Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 188.

- Kagan places these events in 458, while de Ste. Croix is unsure; other scholars also differ.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1.107–8.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 90.

- Diodorus Siculus, Library, 11.81.

- Plutarch, Cimon, 17.3 –4.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 91.

- A.J. Holladay, "Sparta and The First Peloponnesian War," The Journal of Hellenistic Studies Vol. 105. (1985): 162

- Thucydides 1.108

- Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War", 95

- de Ste. Croix, Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 186-7

- See de Ste. Croix, Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 190-6 and Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 80.

- A.J. Holladay, "Sparta and The First Peloponnesian War," The Journal of Hellenistic Studies Vol. 105. (1985): 162.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 97.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 98–102.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 103.

- Diodorus Siculus, Library 11.86.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 107–110.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 111–112.

- Plutarch, Pericles, 17.3

- Thucydides, I, 112.

- Plutarch, Pericles, XXI.

- K. Kuhlmann, Historical Commentary on the Peloponnesian War.

- "Pericles". Encyclopedic Dictionary The Helios. 1952.

- Thucydides, II, 21.

- Aristophanes, The Acharnians, 832.

- Plutarch, Pericles, XXIII.

- Plutarch, Pericles, 22.3

- Meiggs, The Athenian Empire, 111—2.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 128—30

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 128.

References

Primary sources

- Diodorus Siculus, Library

- Plutarch, translated by Bernadotte Perrin, (1914). Lives:Cimon. London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99052-8.

- Polybius, translated by Frank W. Walbank, (1979). The Rise of the Roman Empire. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044362-2.

Secondary sources

- The Encyclopedia of World History (2001)

- Kagan, Donald. The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (Cornell, 1969). ISBN 0-8014-9556-3

- de Ste. Croix, G.E.M., The Origins of the Peloponnesian War, (Duckworth and Co., 1972) ISBN 0-7156-0640-9

1b Second (resumed) Pelopponesian War

From Wikipedia -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peloponnesian_War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian war alliances at 431 BC. Orange: Athenian Empire and Allies; Green: Spartan Confederacy

Date 431 – April 25, 404 BC Location Mainland Greece, Asia Minor, Sicily Result Peloponnesian League victory Territorial

changesDissolution of the Delian League,

Spartan hegemony over Athens and its alliesBelligerents Delian League (led by Athens) Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta)

Support:

PersiaCommanders and leaders Pericles

Cleon †

Nicias (POW) †

Alcibiades

Demosthenes (POW) †Archidamus II

Brasidas †

Lysander

Alcibiades

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases. In the first phase, the Archidamian War, Sparta launched repeated invasions of Attica, while Athens took advantage of its naval supremacy to raid the coast of the Peloponnese attempting to suppress signs of unrest in its empire. This period of the war was concluded in 421 BC, with the signing of the Peace of Nicias. That treaty, however, was soon undermined by renewed fighting in the Peloponnese. In 415 BC, Athens dispatched a massive expeditionary force to attack Syracuse in Sicily; the attack failed disastrously, with the destruction of the entire force, in 413 BC. This ushered in the final phase of the war, generally referred to either as the Decelean War, or the Ionian War. In this phase, Sparta, now receiving support from Persia, supported rebellions in Athens' subject states in the Aegean Sea and Ionia, undermining Athens' empire, and, eventually, depriving the city of naval supremacy. The destruction of Athens' fleet at Aegospotami effectively ended the war, and Athens surrendered in the following year. Corinth and Thebes demanded that Athens should be destroyed and all its citizens should be enslaved but Sparta refused.

The Peloponnesian War reshaped the ancient Greek world. On the level of international relations, Athens, the strongest city-state in Greece prior to the war's beginning, was reduced to a state of near-complete subjection, while Sparta became established as the leading power of Greece. The economic costs of the war were felt all across Greece; poverty became widespread in the Peloponnese, while Athens found itself completely devastated, and never regained its pre-war prosperity.[1][2] The war also wrought subtler changes to Greek society; the conflict between democratic Athens and oligarchic Sparta, each of which supported friendly political factions within other states, made civil war a common occurrence in the Greek world.

Greek warfare, meanwhile, originally a limited and formalized form of conflict, was transformed into an all-out struggle between city-states, complete with atrocities on a large scale. Shattering religious and cultural taboos, devastating vast swathes of countryside, and destroying whole cities, the Peloponnesian War marked the dramatic end to the fifth century BC and the golden age of Greece.[3]

Contents

Prelude

As the preeminent Athenian historian, Thucydides, wrote in his influential History of the Peloponnesian War, "The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Lacedaemon, made war inevitable."[4] Indeed, the nearly fifty years of Greek history that preceded the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War had been marked by the development of Athens as a major power in the Mediterranean world. Its empire began as a small group of city-states, called the Delian League — from the island of Delos, on which they kept their treasury — that came together to ensure that the Greco-Persian Wars were truly over. After defeating the Persian invasion of Greece in the year 480 BC, Athens led the coalition of Greek city-states that continued the Greco-Persian Wars with attacks on Persian territories in the Aegean and Ionia. What then ensued was a period, referred to as the Pentecontaetia (the name given by Thucydides), in which Athens increasingly became in fact an empire,[5] carrying out an aggressive war against Persia and increasingly dominating other city-states. The city proceeded to conquer all of Greece save for Sparta and its allies, ushering in a period which is known to history as the Athenian Empire. By the middle of the century, the Persians had been driven from the Aegean and forced to cede control of a vast range of territories to Athens. At the same time, Athens greatly increased its own power; a number of its formerly independent allies were reduced, over the course of the century, to the status of tribute-paying subject states of the Delian League. This tribute was used to support a powerful fleet and, after the middle of the century, to fund massive public works programs in Athens, ensuring resentment.[6]

Friction between Athens and Peloponnesian states, including Sparta, began early in the Pentecontaetia; in the wake of the departure of the Persians from Greece, Sparta attempted to prevent the reconstruction of the walls of Athens (without the walls, Athens would have been defenseless against a land attack and subject to Spartan control), but was rebuffed.[7] According to Thucydides, although the Spartans took no action at this time, they "secretly felt aggrieved".[8] Conflict between the states flared up again in 465 BC, when a helot revolt broke out in Sparta. The Spartans summoned forces from all of their allies, including Athens, to help them suppress the revolt. Athens sent out a sizable contingent (4,000 hoplites), but upon its arrival, this force was dismissed by the Spartans, while those of all the other allies were permitted to remain. According to Thucydides, the Spartans acted in this way out of fear that the Athenians would switch sides and support the helots; the offended Athenians repudiated their alliance with Sparta.[9] When the rebellious helots were finally forced to surrender and permitted to evacuate the country, the Athenians settled them at the strategic city of Naupactus on the Corinthian Gulf.[10]

In 459 BC, Athens took advantage of a war between its neighbors Megara and Corinth, both Spartan allies, to conclude an alliance with Megara, giving the Athenians a critical foothold on the Isthmus of Corinth. A fifteen-year conflict, commonly known as the First Peloponnesian War, ensued, in which Athens fought intermittently against Sparta, Corinth, Aegina, and a number of other states. For a time during this conflict, Athens controlled not only Megara but also Boeotia; at its end, however, in the face of a massive Spartan invasion of Attica, the Athenians ceded the lands they had won on the Greek mainland, and Athens and Sparta recognized each other's right to control their respective alliance systems.[11] The war was officially ended by the Thirty Years' Peace, signed in the winter of 446/5 BC.[12]

Breakdown of the peace

The Delian League in 431 BCThe Thirty Years' Peace was first tested in 440 BC, when Athens' powerful ally Samos rebelled from its alliance with Athens. The rebels quickly secured the support of a Persian satrap, and Athens found itself facing the prospect of revolts throughout the empire. The Spartans, whose intervention would have been the trigger for a massive war to determine the fate of the empire, called a congress of their allies to discuss the possibility of war with Athens. Sparta's powerful ally of Corinth was notably opposed to intervention, and the congress voted against war with Athens. The Athenians crushed the revolt, and peace was maintained.[13]

The more immediate events that led to war involved Athens and Corinth. After suffering a defeat at the hands of their colony of Corcyra, a sea power that was not allied to either Sparta or Athens, Corinth began to build an allied naval force. Alarmed, Corcyra sought an alliance with Athens, which after debate and input from both Corcyra and Corinth, decided to swear to a defensive alliance with Corcyra. At the Battle of Sybota, a small contingent of Athenian ships played a critical role in preventing a Corinthian fleet from capturing Corcyra. In order to uphold the Thirty Years' Peace, however, the Athenians were instructed not to intervene in the battle unless it was clear that Corinth was going to press onward to invade Corcyra. However, the Athenian warships participated in the battle nevertheless, and the arrival of additional Athenian warships was enough to dissuade the Corinthians from exploiting their victory, thus sparing much of the routed Corcyraean and Athenian fleet.[14]

Following this, Athens instructed Potidaea (Chalcidice peninsula), a tributary ally of Athens but a colony of Corinth, to tear down its walls, send hostages to Athens, dismiss the Corinthian magistrates from office, and refuse the magistrates that the city would send in the future.[15] The Corinthians, outraged by these actions, encouraged Potidaea to revolt and assured them that they would ally with them should they revolt from Athens. Meanwhile, the Corinthians were unofficially aiding Potidaea by sneaking contingents of men into the besieged city to help defend it. This was a direct violation of the Thirty Years' Peace, which had (among other things) stipulated that the Delian League and the Peloponnesian League would respect each other's autonomy and internal affairs.

A further source of provocation was an Athenian decree, issued in 433/2 BC, imposing stringent trade sanctions on Megarian citizens (once more a Spartan ally after the conclusion of the First Peloponnesian War). It was alleged that the Megarians had desecrated the Hiera Orgas. These sanctions, known as the Megarian decree, were largely ignored by Thucydides, but some modern economic historians have noted that forbidding Megara to trade with the prosperous Athenian empire would have been disastrous for the Megarans, and have accordingly considered the decree to be a contributing factor in bringing about the war.[16] Historians that attribute responsibility for the war to Athens cite this event as the main cause for blame.[17]

At the request of the Corinthians, the Spartans summoned members of the Peloponnesian League to Sparta in 432 BC, especially those who had grievances with Athens to make their complaints to the Spartan assembly. This debate was attended by members of the league and a delegation from Athens (that was not invited) also asked to speak, and became the scene of a debate between the Athenians and the Corinthians. Thucydides reports that the Corinthians condemned Sparta's inactivity up to that point, warning the Spartans that if they continued to remain passive while the Athenians were energetically active, they would soon find themselves outflanked and without allies.[18] The Athenians, in response, reminded the Spartans of their record of military success and opposition to Persia, and warned them of the dangers of confronting such a powerful state, ultimately encouraging Sparta to seek arbitration as provided by the Thirty Years' Peace.[19] Undeterred, a majority of the Spartan assembly voted to declare that the Athenians had broken the peace, essentially declaring war.[20]

The "Archidamian War"

The walls surrounding AthensSparta and its allies, with the exception of Corinth, were almost exclusively land-based powers, able to summon large land armies which were very nearly unbeatable (thanks to the legendary Spartan forces). The Athenian Empire, although based in the peninsula of Attica, spread out across the islands of the Aegean Sea; Athens drew its immense wealth from tribute paid from these islands. Athens maintained its empire through naval power. Thus, the two powers were relatively unable to fight decisive battles.

The Spartan strategy during the first war, known as the Archidamian War (431-421 BC) after Sparta's king Archidamus II, was to invade the land surrounding Athens. While this invasion deprived Athenians of the productive land around their city, Athens itself was able to maintain access to the sea, and did not suffer much. Many of the citizens of Attica abandoned their farms and moved inside the long walls, which connected Athens to its port of Piraeus. At the end of the first year of the war, Pericles gave his famous Funeral Oration (431 BC).

The Spartans also occupied Attica for periods of only three weeks at a time; in the tradition of earlier hoplite warfare the soldiers were expected to go home to participate in the harvest. Moreover, Spartan slaves, known as helots, needed to be kept under control, and could not be left unsupervised for long periods of time. The longest Spartan invasion, in 430 BC, lasted just forty days.

The Athenian strategy was initially guided by the strategos, or general, Pericles, who advised the Athenians to avoid open battle with the far more numerous and better trained Spartan hoplites, relying instead on the fleet. The Athenian fleet, the most dominant in Greece, went on the offensive, winning a victory at Naupactus. In 430 BC an outbreak of a plague hit Athens. The plague ravaged the densely packed city, and in the long run, was a significant cause of its final defeat. The plague wiped out over 30,000 citizens, sailors and soldiers, including Pericles and his sons. Roughly one-third to two-thirds of the Athenian population died. Athenian manpower was correspondingly drastically reduced and even foreign mercenaries refused to hire themselves out to a city riddled with plague. The fear of plague was so widespread that the Spartan invasion of Attica was abandoned, their troops being unwilling to risk contact with the diseased enemy.

After the death of Pericles, the Athenians turned somewhat against his conservative, defensive strategy and to the more aggressive strategy of bringing the war to Sparta and its allies. Rising to particular importance in Athenian democracy at this time was Cleon, a leader of the hawkish elements of the Athenian democracy. Led militarily by a clever new general Demosthenes (not to be confused with the later Athenian orator Demosthenes), the Athenians managed some successes as they continued their naval raids on the Peloponnese. Athens stretched their military activities into Boeotia and Aetolia, quelled the Mytilenean revolt and began fortifying posts around the Peloponnese. One of these posts was near Pylos on a tiny island called Sphacteria, where the course of the first war turned in Athens's favour. The post off Pylos struck Sparta where it was weakest: its dependence on the helots. Sparta was dependent on a class of slaves, known as helots, to tend the fields while its citizens trained to become soldiers. The helots made the Spartan system possible, but now the post off Pylos began attracting helot runaways. In addition, the fear of a general revolt of helots emboldened by the nearby Athenian presence drove the Spartans to action. Demosthenes, however, outmanoeuvred the Spartans in the Battle of Pylos in 425 BC and trapped a group of Spartan soldiers on Sphacteria as he waited for them to surrender. Weeks later, though, Demosthenes proved unable to finish off the Spartans. After boasting that he could put an end to the affair in the Assembly, the inexperienced Cleon won a great victory at the Battle of Sphacteria. The Athenians captured between 300 and 400 Spartan hoplites. The hostages gave the Athenians a bargaining chip.

After these battles, the Spartan general Brasidas raised an army of allies and helots and marched the length of Greece to the Athenian colony of Amphipolis in Thrace, which controlled several nearby silver mines; their product supplied much of the Athenian war fund. Thucydides was dispatched with a force which arrived too late to stop Brasidas capturing Amphipolis; Thucydides was exiled for this, and, as a result, had the conversations with both sides of the war which inspired him to record its history. Both Brasidas and Cleon were killed in Athenian efforts to retake Amphipolis (see Battle of Amphipolis). The Spartans and Athenians agreed to exchange the hostages for the towns captured by Brasidas, and signed a truce.

Peace of Nicias

Main article: Peace of NiciasWith the death of Cleon and Brasidas, zealous war hawks for both nations, the Peace of Nicias was able to last for some six years. However, it was a time of constant skirmishing in and around the Peloponnese. While the Spartans refrained from action themselves, some of their allies began to talk of revolt. They were supported in this by Argos, a powerful state within the Peloponnese that had remained independent of Lacedaemon. With the support of the Athenians, the Argives succeeded in forging a coalition of democratic states within the Peloponnese, including the powerful states of Mantinea and Elis. Early Spartan attempts to break up the coalition failed, and the leadership of the Spartan king Agis was called into question. Emboldened, the Argives and their allies, with the support of a small Athenian force under Alcibiades, moved to seize the city of Tegea, near Sparta.

The Battle of Mantinea was the largest land battle fought within Greece during the Peloponnesian War. The Lacedaemonians, with their neighbors the Tegeans, faced the combined armies of Argos, Athens, Mantinea, and Arcadia. In the battle, the allied coalition scored early successes, but failed to capitalize on them, which allowed the Spartan elite forces to defeat the forces opposite them. The result was a complete victory for the Spartans, which rescued their city from the brink of strategic defeat. The democratic alliance was broken up, and most of its members were reincorporated into the Peloponnesian League. With its victory at Mantinea, Sparta pulled itself back from the brink of utter defeat, and re-established its hegemony throughout the Peloponnese.

Sicilian Expedition

Main article: Sicilian ExpeditionSicily and the Peloponnesian WarIn the 17th year of the war, word came to Athens that one of their distant allies in Sicily was under attack from Syracuse. The people of Syracuse were ethnically Dorian (as were the Spartans), while the Athenians, and their ally in Sicilia, were Ionian. The Athenians felt obliged to assist their ally.

The Athenians did not act solely from altruism: rallied on by Alcibiades, the leader of the expedition, they held visions of conquering all of Sicily. Syracuse, the principal city of Sicily, was not much smaller than Athens, and conquering all of Sicily would have brought Athens an immense amount of resources. In the final stages of the preparations for departure, the hermai (religious statues) of Athens were mutilated by unknown persons, and Alcibiades was charged with religious crimes. Alcibiades demanded that he be put on trial at once, so that he might defend himself before the expedition. The Athenians however allowed Alcibiades to go on the expedition without being tried (many believed in order to better plot against him). After arriving in Sicily, Alcibiades was recalled back to Athens for trial. Fearing that he would be unjustly condemned, Alcibiades defected to Sparta and Nicias was placed in charge of the mission. After his defection, Alcibiades claimed to the Spartans that the Athenians planned to use Sicily as a springboard for the conquest of all of Italy and Carthage, and to use the resources and soldiers from these new conquests to conquer the Peloponnese.

The Athenian force consisted of over 100 ships and some 5,000 infantry and light-armored troops. Cavalry was limited to about 30 horses, which proved to be no match for the large and highly trained Syracusan cavalry. Upon landing in Sicily, several cities immediately joined the Athenian cause. Instead of attacking at once, Nicias procrastinated and the campaigning season of 415 BC ended with Syracuse scarcely damaged. With winter approaching, the Athenians were then forced to withdraw into their quarters, and they spent the winter gathering allies and preparing to destroy Syracuse. The delay allowed the Syracusans to send for help from Sparta, who sent their general Gylippus to Sicily with reinforcements. Upon arriving, he raised up a force from several Sicilian cities, and went to the relief of Syracuse. He took command of the Syracusan troops, and in a series of battles defeated the Athenian forces, and prevented them from invading the city.

Nicias then sent word to Athens asking for reinforcements. Demosthenes was chosen and led another fleet to Sicily, joining his forces with those of Nicias. More battles ensued and again, the Syracusans and their allies defeated the Athenians. Demosthenes argued for a retreat to Athens, but Nicias at first refused. After additional setbacks, Nicias seemed to agree to a retreat until a bad omen, in the form of a lunar eclipse, delayed any withdrawal. The delay was costly and forced the Athenians into a major sea battle in the Great Harbor of Syracuse. The Athenians were thoroughly defeated. Nicias and Demosthenes marched their remaining forces inland in search of friendly allies. The Syracusan cavalry rode them down mercilessly, eventually killing or enslaving all who were left of the mighty Athenian fleet.

The Second War

The Lacedaemonians were not content with simply sending aid to Sicily; they also resolved to take the war to the Athenians. On the advice of Alcibiades, they fortified Decelea, near Athens, and prevented the Athenians from making use of their land year round. The fortification of Decelea prevented the shipment of supplies overland to Athens, and forced all supplies to be brought in by sea at increased expense. Perhaps worst of all, the nearby silver mines were totally disrupted, with as many as 20,000 Athenian slaves freed by the Spartan hoplites at Decelea. With the treasury and emergency reserve fund of 1,000 talents dwindling away, the Athenians were forced to demand even more tribute from her subject allies, further increasing tensions and the threat of further rebellion within the Empire.

The Corinthians, the Spartans, and others in the Peloponnesian League sent more reinforcements to Syracuse, in the hopes of driving off the Athenians; but instead of withdrawing, the Athenians sent another hundred ships and another 5,000 troops to Sicily. Under Gylippus, the Syracusans and their allies were able to decisively defeat the Athenians on land; and Gylippus encouraged the Syracusans to build a navy, which was able to defeat the Athenian fleet when they attempted to withdraw. The Athenian army, attempting to withdraw overland to other, more friendly Sicilian cities, was divided and defeated; the entire Athenian fleet was destroyed, and virtually the entire Athenian army was sold off into slavery.

Following the defeat of the Athenians in Sicily, it was widely believed that the end of the Athenian Empire was at hand. Her treasury was nearly empty, her docks were depleted, and the flower of her youth was dead or imprisoned in a foreign land. They overestimated the strength of their own empire and the beginning of the end was indeed at hand.

Athens recovers

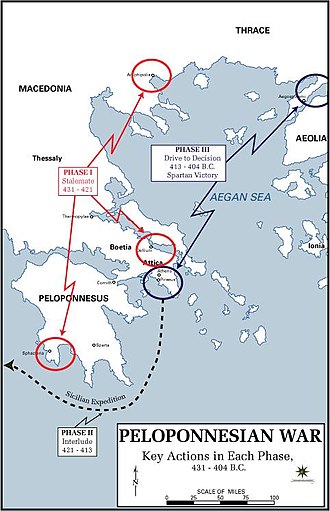

The key actions of each phaseFollowing the destruction of the Sicilian Expedition, Lacedaemon encouraged the revolt of Athens's tributary allies, and indeed, much of Ionia rose in revolt against Athens. The Syracusans sent their fleet to the Peloponnesians, and the Persians decided to support the Spartans with money and ships. Revolt and faction threatened in Athens itself.

The Athenians managed to survive for several reasons. First, their foes were lacking in initiative. Corinth and Syracuse were slow to bring their fleets into the Aegean, and Sparta's other allies were also slow to furnish troops or ships. The Ionian states that rebelled expected protection, and many rejoined the Athenian side. The Persians were slow to furnish promised funds and ships, frustrating battle plans.

At the start of the war, the Athenians had prudently put aside some money and 100 ships that were to be used only as a last resort.

These ships were then released, and served as the core of the Athenians' fleet throughout the rest of the war. An oligarchical revolution occurred in Athens, in which a group of 400 seized power. A peace with Sparta might have been possible, but the Athenian fleet, now based on the island of Samos, refused to accept the change. In 411 BC this fleet engaged the Spartans at the Battle of Syme. The fleet appointed Alcibiades their leader, and continued the war in Athens's name. Their opposition led to the reinstitution of a democratic government in Athens within two years.

Alcibiades, while condemned as a traitor, still carried weight in Athens. He prevented the Athenian fleet from attacking Athens; instead, he helped restore democracy by more subtle pressure. He also persuaded the Athenian fleet to attack the Spartans at the battle of Cyzicus in 410. In the battle, the Athenians obliterated the Spartan fleet, and succeeded in re-establishing the financial basis of the Athenian Empire.

Between 410 and 406, Athens won a continuous string of victories, and eventually recovered large portions of its empire. All of this was due, in no small part, to Alcibiades.

Lysander triumphs, Athens surrenders

Faction triumphed in Athens following a minor Spartan victory by their skillful general Lysander at the naval battle of Notium in 406 BC. Alcibiades was not re-elected general by the Athenians and he exiled himself from the city. He would never again lead Athenians in battle. Athens was then victorious at the naval battle of Arginusae. The Spartan fleet under Callicratidas lost 70 ships and the Athenians lost 25 ships. But, due to bad weather, the Athenians were unable to rescue their stranded crews or to finish off the Spartan fleet. Despite their victory, these failures caused outrage in Athens and led to a controversial trial. The trial resulted in the execution of six of Athens’s top naval commanders. Athens’s naval supremacy would now be challenged without several of its most able military leaders and a demoralized navy.

Unlike some of his predecessors the new Spartan general, Lysander, was not a member of the Spartan royal families and was also formidable in naval strategy; he was an artful diplomat, who had even cultivated good personal relationships with the Persian prince Cyrus, the son of Darius II. Seizing its opportunity, the Spartan fleet sailed at once to the Hellespont, the source of Athens' grain. Threatened with starvation, the Athenian fleet had no choice but to follow. Through cunning strategy, Lysander totally defeated the Athenian fleet, in 405 BC, at the battle of Aegospotami, destroying 168 ships and capturing some three or four thousand Athenian sailors. Only 12 Athenian ships escaped, and several of these sailed to Cyprus, carrying the "strategos" (General) Conon, who was anxious not to face the judgment of the Assembly.

Facing starvation and disease from the prolonged siege, Athens surrendered in 404 BC, and its allies soon surrendered as well. The democrats at Samos, loyal to the bitter last, held on slightly longer, and were allowed to flee with their lives. The surrender stripped Athens of its walls, its fleet, and all of its overseas possessions. Corinth and Thebes demanded that Athens should be destroyed and all its citizens should be enslaved. However, the Spartans announced their refusal to destroy a city that had done a good service at a time of greatest danger to Greece, and took Athens into their own system. Athens was "to have the same friends and enemies"[21] as Sparta.

Aftermath

For a short period of time, Athens was ruled by the "Thirty Tyrants" and democracy was suspended. This was a reactionary regime set up by Sparta. The oligarchs were overthrown and a democracy was restored by Thrasybulus in 403 BC.

Although the power of Athens was broken, it made something of a recovery as a result of the Corinthian War and continued to play an active role in Greek politics. Sparta was later humbled by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC, but the rivalry of Athens and Sparta was brought to an end a few decades later when Philip II of Macedon conquered all of Greece except Sparta.

Notes

- Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 488.

- Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 528–33.

- Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, Introduction XXIII–XXIV.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.23

- Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 371

- Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 8

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.89–93

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.92.1

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.102

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.103

- Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 16–18

- In the Hellenic calendar, years ended at midsummer; as a result, some events cannot be dated to a specific year of the modern calendar.

- Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 23–24

- Thucydides, Book I, 49-50

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.56

- Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 454–456

- Buckley Aspects of Greek History, 319–322

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.67–71

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.73–75

- Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 45.

- Xenophon, Hellenica, 2.2.20,404/3

------------------------------------------------References and further reading

Classical authors

Eight bookes of the Peloponnesian Warre written by Thucydides the sonne of Olorus. Interpreted with faith and diligence immediately out of the Greeke by Thomas Hobbes secretary to ye late Earle of Deuonshire. (Houghton Library)

- Aristophanes, Lysistrata

- Diodorus Siculus

- Herodotus, Histories sets the table of events before Peloponnesian War that deals with Greco-Persian Wars and the formation of the Classical Greece

- Plutarch, known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

- Xenophon, Hellenica

Modern authors

- Bagnall, Nigel. The Peloponnesian War: Athens, Sparta, And The Struggle For Greece. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-312-34215-2).

- Cawkwell, George. Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War. London: Routledge, 1997 (hardcover, ISBN 0-415-16430-3; paperback, ISBN 0-415-16552-0).

- Hanson, Victor Davis. A War Like No Other: How the Athenians and Spartans Fought the Peloponnesian War. New York: Random House, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 1-4000-6095-8); New York: Random House, 2006 (paperback, ISBN 0-8129-6970-7).

- Heftner, Herbert. Der oligarchische Umsturz des Jahres 411 v. Chr. und die Herrschaft der Vierhundert in Athen: Quellenkritische und historische Untersuchungen. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001 (ISBN 3-631-37970-6).

- Hutchinson, Godfrey. Attrition: Aspects of Command in the Peloponnesian War. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-86227-323-5).

- Kagan, Donald:

- The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1969 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-0501-7); 1989 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9556-3).

- The Archidamian War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-0889-X); 1990 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9714-0).

- The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-1367-2); 1991 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9940-2).

- The Fall of the Athenian Empire. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-1935-2); 1991 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9984-4).

- The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003 (hardcover, ISBN 0-670-03211-5); New York: Penguin, 2004 (paperback, ISBN 0-14-200437-5); a one-volume version of his earlier tetralogy.

- Kallet, Lisa. Money and the Corrosion of Power in Thucydides: The Sicilian Expedition and its Aftermath. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-22984-3).

- Krentz, Peter. The Thirty at Athens. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1982 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-1450-4).

- The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War, edited by Robert B. Strassler. New York: The Free Press, 1996 (hardcover, ISBN 0-684-82815-4); 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-684-82790-5).

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peloponnesian War.

- LibriVox: The History of the Peloponnesian War (Public Domain Audiobooks in the USA - 20:57:23 hours, at least 603.7 MB)

- Richard Crawley, The History of the Peloponnesian War (Translation of Thukydides' books – in Project Gutenberg)

- Peloponnesian war

- Peloponnesian war on Lycurgus.org

2 Peloponnesian War

From Livius http://www.livius.org/pb-pem/peloponnesian_war/peloponnesian_war.html

Peloponnesian War: name of the conflict between Athens and Sparta that broke out in 431 and continued, with an interruption, until 404. Athens was forced to dismantle its empire. The war however, was not decisive, because within a decade, the defeated city had regained its strength. The significance of the conflict is that the divided Greeks could not prevent the Persian Empire from recovering their Asian possessions. Besides, this violent quarter of a century had important social, economic, and cultural consequences.

1: Sources

Our main source for the Peloponnesian War is the History by the Athenian author Thucydides. He is a great historian who tries to be objective, but his work must be read with caution, because he has his sympathies (e.g., for Hermocrates and Nicias) and antipathies (e.g., Cleon and Theramenes). Modern scholars offer interpretations of the war that are different from Thucydides'.Other sources are inscriptions, a couple of contemporary speeches, remarks in the Histories by Herodotus of Halicarnassus, references in Aristophanes' comedies, Xenophon's Hellenica, the Athenian Constitution by an anonymous student of Aristotle of Stagira, Books 12-13 of the Library of World History by Diodorus of Sicily and the Lifes by Plutarch of Chaeronea. (The two last-mentioned authors lived during the Roman empire but used older sources like Ephorus of Cyme.)

2: Outline2.1: Causes

When Athens concluded an alliance with Corcyra (modern Corfu) in 433, and started to besiege Potidaea, it threatened the position of Corinth. Sparta also feared that Athens was becoming too powerful but tried to prevent war. Peace was possible, the Spartans said, when Athens would revoked measures against Sparta's ally Megara. The Athenian leader Pericles refused this, because Sparta and Athens had once agreed that conflicts would be solved by arbitration. If the Athenians would yield to Sparta's request, they would in fact accept Spartan orders. This was unacceptable, and war broke out: Athens and its Delian League were attacked by Sparta and its Peloponnesian League. Diodorus mentions that the Spartans did not just declare war, but decided to declare war and ask for help in Persia (World History, 12.41.1).

2.2: Archidamian War (longer version)

When Sparta declared war, it announced that it wanted to liberate Greece from Athenian oppression. And with some justification, because Athens had converted the Delian League, which had once been meant as a defensive alliance against the Persian Empire, into an Athenian empire.To achieve victory, Sparta had to force Athens into some kind of surrender; on the other hand, Athens simply had to survive the attacks. Pericles' strategy was to abandon the countryside to the Spartans and concentrate everyone in the city itself, which could receive supplies from across the sea. As long as the "Long walls" connected the city to its port Piraeus, as long as Athens ruled the waves, and as long as Athens was free to strike from the sea against Sparta's coastal allies, it could create tensions within the Spartan alliance.

In 431 and 430, the Spartan king Archidamus II invaded Attica (the countryside of Athens) and laid waste large parts of it. The Athenian admiral Phormio retaliated with attacks on the Spartan navy (text). However, it soon became apparent that Pericles' strategy was too expensive. Worse was to come, because in 429, a terrible plague took away about a third of the Athenian citizens, including Pericles. At the same time, the Spartans laid siege to Plataea (text), which fell in 427.

Pericles (British Museum, London)

Believing that Athens was about to collapse, the island of Lesbos revolted and Archidamus invaded Attica again. However, the Athenians were not defeated at all.They suppressed the revolt and at the same time embarked upon a more aggressive policy, launching a small expedition to Sicily. In 425, the Athenian general Demosthenes and the statesman Cleon, who had earlier tripled the Athenian income and saved Athens from bankruptcy, captured 292 Spartans on the island Sphacteria (text). The Athenians also built a fortress at Pylos, where they could receive runaway slaves and helots. This did great damage to the Spartan economy.For the Spartans, invading Attica was now impossible (the POWs would be executed), so they attacked Athenian possessions in the northern Aegean. The Spartan Brasidas provoked rebellions in this area and captured the strategically important Athenian colony of Amphipolis (text). (The Athenian Thucydides, who could not save the town, was punished with exile and became this war's historian.)

When Cleon and Brasidas were killed in action during an Athenian attempt to recover Amphipolis, a treaty was signed: the Peace of Nicias (421). Athens had won the Archidamian War.

Alcibiades (Musei Capitolini, Roma)

2.3: The entr'acte (longer version)

The next years witnessed a continuation of the war with diplomatic means. Athens and Sparta had concluded a defensive alliance, but on both sides, there were politicians who wanted to resume the war. The Spartans did not return Amphipolis, as they had promised, and the Athenians replied by keeping Sphacteria and Pylos.Now, the Athenian politician Alcibiades launched a new policy that promised the collapse of the Peloponnesian League without much Athenian involvement. Following his advice, the Athenians joined a coalition with three democratic states on the Peloponnese: Argos, Mantinea, and Elis. Athens now had friends in the Spartan backyard and had cut off the route between Sparta and its northern allies Corinth and Thebes.

The Spartans knew how to reply. If it attacked the Athenian allies, Athens would be forced to choose between either its Spartan alliance (which meant abandoning its allies), or its treaty with Argos, Mantinea, and Elis (and risking an open war with Sparta in the Peloponnese). As it turned out, Athens preferred the second alternative, and when the Spartan king Agis II marched to the north, Athens supported the democrats. In 418, a battle was fought at Mantinea, and the Spartan king Agis defeated his enemies (text).

As a result, Sparta restored its prestige, the quadruple alliance was dissolved, and democracy suffered a severe blow. The prestige of the frustrated Athenians needed a boost, and in an act of folly they made the fatal mistake for which they would in the end pay with the loss of their empire. In 420, the satrap of Lydia, Pissuthnes, had revolted against the Achaemenid king Darius II Nothus. The great king's representative Tissaphernes arrested the rebel and sent him to Darius, who had him executed. Pissuthnes' son Amorges, however, continued the struggle and received help from Athens. Consequently, Darius would ultimately side with Sparta.

2.4: The Sicilian Expedition (longer version)

As already noticed above, an Athenian navy had already shown itself in the far west in 427, and the Athenians had allies on Sicily. After Sparta and Athens had concluded a peace treaty in 421, the Athenians had their hands free and sent out an armada to conquer the island. Some, including the popular leader Hyperbolus, wanted even bigger things, like an attack on Carthage. For the time being, however, the plan was to conquer Sicily only. The commanders were Lamachus, Nicias, and Alcibiades. In 415, the expedition started.The first year of the Sicilian war was more successful for the invaders than for the defenders. The Athenians created a base in Catana and defeated the Syracusans in battle. Still, they had not won the war yet, and the death of Lamachus, the recall of Alcibiades (who was involved in a religious scandal), and an illness of Nicias created serious problems.

During the winter of 415/414, the Syracusan democratic leader Hermocrates convinced his compatriots to extend their city's fortifications and reorganize the structure of command. The new system, however, was not a great improvement, and the Athenians laid siege to Syracuse.

The arrival of a Spartan military adviser, Gylippus, turned the tables. Although the Athenians sent reinforcements to Syracuse, commanded by Demosthenes, they had not enough cavalry. To make matters worse, in 413, the Spartans declared war upon Athens, which made it impossible to send the necessary horses. In the end, the Athenian expeditionary force was completely destroyed (text).

2.5: The Decelean or Ionian War (longer version)

Many people believed that the end of the Delian League was near. Athens had no experienced leaders anymore: Alcibiades was in exile and lived in Sparta, Demosthenes, Lamachus, and Nicias were dead, and the popular Hyperbolus had been ostracized.Even worse, he Spartan king Agis had built a fortress in Attica, at Decelea. The countryside was now constantly pillaged and the Athenians no longer had access to the silver mines of Laureion. Meanwhile, the Peloponnesian League dared to send a fleet to the Aegean Sea. The satraps Tissaphernes of Lydia and Pharnabazus of Hellespontine Phrygia offered money to Sparta, both hoping to achieve military support for the great king's aims in return.

Because the Spartans had hardly any naval experience, they had to turn to an Athenian when Chios revolted from Athens: Alcibiades. He led the Spartan fleet to Chios, reinforced the insurrectionists and made sure that the revolt pread to other towns.

At this moment, the Spartans concluded a treaty with king Darius II Nothus, who offered pay for the Spartan navy (412/411). Tissaphernes was to be the king's agent, but he believed that an unconditional alliance with Sparta was not in the interests of Persia, so he delayed payments and more than once threatened to negotiate with Athens.

The Persian-Spartan coalition ultimately brought down Athens, but the city was not defeated yet. Athens had faced a similar coalition in 461-448 and back then, it had achieved remarkable results. However, after the Sicilian disaster, this was no longer possible. Still, the Athenians responded to the challenge, founded a base on the isle of Samos, and attacked Chios.

At this point, Alcibiades told the Athenians that he would bring over the great king to their side if Athens recalled him and gave up its democracy. Indeed, a man named Peisander conducted an extreme oligarchic coup in Athens in 411 (text). Among the other leaders of the Four Hundred were Antiphon, who sincerely believed that oligarchy was preferable to democracy, and a general named Theramenes, who argued that if the suspension of democracy could bring Persian support, it was worth a try. From the very first start, the oligarchs were divided.

A new crisis faced the Athenians when the cities near the Hellespont revolted, including those on the Bosphorus. This imperiled the Athenian grain supply, and the men on the Athenian fleet -led by Thrasybulus- recalled Alcibiades. More or less at the same time, a Spartan fleet occupied Euboea, where the Athenians had left their cattle. In this crisis, the Four Hundred were replaced by the moderate oligarchy that had been proposed by Theramenes. Power now was in the hands of the Five Thousand, i.e., those who "served the state with a horse or a shield".

Meanwhile, the Spartans decided to move the war to the Hellespont and cut off the grain supply of Athens. Admiral Mindarus brought the Spartan fleet to the north, but was defeated by the Athenian admirals Thrasybulus and Thrasyllus. When the year 410 started, all Athenian commanders -Alcibiades, Theramenes, Thrasybulus, and Thrasyllus- were in the Hellespont, where they decisively defeated the Spartan navy near Cyzicus. Its admiral Mindarus was killed in action.

The Spartans now offered peace but the Athenian popular leader Cleophon, who did not trust the Spartans after their hesitation to implement the terms of the Peace of Nicias, convinced the people that it was better to refuse. The rejection of the peace offer may have been the moment when democracy was restored.

Now, the war came to a standstill. Sparta was unable to strike and the Athenian democrats were not happy with the successful admirals: after all, Alcibiades, Theramenes, Thrasybulus, and Thrasyllus had collaborated with the oligarchs. They were left in office, but were not reinforced. Still they recovered some ground in Ionia and regained control of the Bosphorus. It seemed as if the Athenians were slowly winning the war after all.

However, one of Alcibiades' deputies was defeated in a battle near Notion and the Athenians sent Alcibiades away from their city again, and this time for good. This gave new self-confidence to the Spartans. Their new and capable admiral Lysander was lucky to find a new satrap in Lydia, prince Cyrus the Younger, who had orders to support Sparta unconditionally.

Athens was now doomed. In 406, it was still able to defeat the Spartans in a naval battle at the Arginusae, but a gathering storm prevented the victorious admirals from picking the survivors from the water. Back home, they were condemned to death.

Again, Athens had no experienced commanders. In 405, Lysander was active in the Hellespont and defeated the Athenians at the Aigospotamoi. Their entire fleet was destroyed (text). The war was over: only the capture of Athens remained. Three Spartan armies, commanded by king Agis, king Pausanias, and Lysander, started to besiege the city.

During the winter, Theramenes conducted negotiations, and in April 404, Athens surrendered (text). It gave up its empiree, joined the Peloponnesian League, and accepted a regime of thirty oligarchs, which included the radical Critias and the moderate Theramenes (text). According to Xenophon, the Spartans "tore down the Long Walls among scenes of great joy and to the music of flute girls" (Hellenica 2.2.24).

2.6: Aftermath (longer version)

The regime of the Thirty was impopular and alienated Sparta from its friends. The Thebans grew suspicious of the Spartan occupation of Athens, and started to support the democrats under Thrasybulus, who occupied Phyle, a fortress on the border of Attica and Boeotia.

The Thirty were divided and tried to close their ranks. An even closer association with Sparta seemed the best way to remain in power, and the moderate Theramenes was executed. At the end of 404, the democrats took Piraeus and started a civil war that lasted until September 403, when the Spartan king Pausanias restored democracy (text).

Sparta owed much to prince Cyrus, who needed help when his father Darius II Nothus was in 404 succeeded by Artaxerxes II Mnemon. The Spartan Clearchus, probably acting with tacit approval of his government, supported Cyrus when he revolted. Many Greek mercenaries joined the expedition, which culminated in 401 in the battle of Cunaxa, in which Cyrus was killed.

After this, the Spartans interfered even more in the Persian zone of influence. King Agesilaus invaded Asia and had considerable success. Now, the Persians started to support Athens, which rebuilt its Long Walls (395). Next year, Conon, the Athenian admiral who had fallen into disfavor after the battle at the Aigospotamoi, returned with a large fleet. Athens had fully recovered.

Or so it seemed. Of course, it owed its restoration to Persian money. The only victor in the Peloponnesian War was the great king.

3: Consequences

- In Athens, the democratic system survived. Even without the income generated by the empire, democracy proved to be a well-functioning political system.

- This can partly be explained from the fact that during the war, the economy of Athens changed. Once, most Athenians had been peasants; after the outbreak of the Decelean War, trade and commerce became increasingly important. These activities were almost as profitable as the old empire.

- Thebes increased in strength and became a major power. Sparta, on the other hand, only temporarily benefited from its victory. Its social structure was unsuited for a world larger than the Peloponnese. In the fifth century, Greece had been a bipolar political system, but changed into a multipolar system.

- The great victor was, of course, Persia. Not only did it regain the Greek towns in Asia, but it was to have great diplomatic influence among the "Yaun�".

- Many people had been exiled and had become mercenaries to make a living. Others had become professional soldiers because they could no longer return to their farms. Warfare became a specialism.

4: Literature

- There are many books on this war. As a first introduction, read Thucydides' History and continue with Xenophon's Hellenica.

- Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War. Athens and Sparta in Savage Conflict, 431-404 BC (2003) is an excellent and accessible narrative written by one of America's foremost conservative thinkers. If you want to read only one book, this is your best choice. From the same author:

- The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (1969),

- The Archidamian War (1974),

- The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition (1981),

- The Fall of the Athenian Empire (1987).

- Simon Hornblower, The Greek World, 479-323 BC (2002�) contains three chapters with highly condensed information: "The run-up to the war" (103-110), "The Peloponnesian War" (150-183), and "The effects of the Peloponnesian War" (184-209). The second of these offers a religious interpretation of the war that would have horrified Thucydides but is probably correct.

- More specialized literature can be found in the bibliography of Hornblower's book. Five titles are especially important:

- G.L. Cawkwell, Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War (1997 London)

- H. Heftner, Der oligarchische Umsturz des Jahres 411 v.Chr. und die Herrschaft der Vierhundert in Athen (2001 Frankfurt am Main)

- Simon Hornblower, Thucydides (1994� London)

- L. Kallet, Money and the Corrosion of Power in Thucydides. The Sicilian Expedition and its Aftermath (2001 Berkeley)

- P. Krentz, The Thirty at Athens, (1982 Ithaca and London)

5: Translated texts on this website

- The Megarian Decree (Aristophanes)

- Outbreak of war (Thucydides)

- Aneristus and Nicolaus (Thucydides)

- The plague (Thucydides)

- Naval warfare: Phormio's first victory (Thucydides)

- Siege warfare: Plataea (Thucydides)

- The Sphacteria Campaign (Diodorus)

- The fall of Amphipolis (Thucydides)

- The Peace (Aristophanes)

- The Peace of Nicias

- Hoplite battle: Mantinea (Thucydides)

- The end of the Sicilian expedition (Thucydides)

- Treaties between Sparta and Persia

- Assessment of Amorges (Andocides)

- The oligarchic coup of 411 (Ps.-Aristotle)

- The battle of Aigospotamoi (Xenophon)

- The surrender of Athens (Xenophon)

- The regime of the Thirty (Ps.-Aristotle)

- Rewards for the liberators of Athens (Inscription)

6: Related

- Common Errors (10): Aspasia

- Common Errors (22): Pericles' Preparations

- Common Errors (23): The Sicilian Expedition

---------------------------------------------------------

3 Thucydides The History of the Peloponnesian WarThe History of the Peloponnesian War has been divided into the following sections:

From http://classics.mit.edu/Thucydides/pelopwar.html

Written in 431 BC

Translated by Richard Crawley (First book published in 1866, full work published in 1874.)

The Third Book [187k]The Fourth Book [220k]

The Fifth Book [169k]

The Sixth Book [187k]The Seventh Book [164k]

The Eighth Book [187k]

Download: A 1153k text-only version is available for download.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

AudioBook of the full Crawley translation is at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYYQvnXzDpM

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

4 Spartan Invasion Sparta -- War Of Empire -- History Documentary

5 Corinthian War Postscript

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corinthian_War

Corinthian War Part of the Spartan hegemony

Hoplites in combat

Date 395–387 BC Location Mainland Greece Result Inconclusive;

Peace of Antalcidas dictated by PersiaTerritorial

changesIonia ceded to Persia,

Boeotian league dissolved,

Union of Argos and Corinth dissolvedBelligerents Sparta

Peloponnesian LeagueAthens

Argos

Corinth

Thebes

Persian Empire

Other alliesCommanders and leaders Agesilaus and others Numerous

The Corinthian War was an ancient Greek conflict lasting from 395 BC until 387 BC, pitting Sparta against a coalition of four allied states, Thebes, Athens, Corinth, and Argos, who were initially backed by Persia. The immediate cause of the war was a local conflict in northwest Greece in which both Thebes and Sparta intervened. The deeper cause was hostility towards Sparta provoked by that city's "expansionism in Asia Minor, central and northern Greece and even the west".[1]