This page is on the internet at http://www.mmdtkw.org/GR--Unit15-ClassicalGreekTheater-Readings.html

Readings for Ancient Greece 2 -- Unit 15, Classical Greek Theater

[Text in colored letters are Internet links; click on links to go to additional information. Use your web browser "back" or "return" link to come back to this page.]

Make sure to take a look at the Kennedy Center's CITY DIONYSIA interactive Internet site about Ancient Greek theater. It's named after the annual Dionysia theater festival of Ancient Athens

As it was with architecture, so it was also with Greek theater and drama -- it was mostly an Athenian phenomenon.

Ancient Greek theater flourished from c. 700 BC, but its greatest dramatists wrote during the Classical Period (after ca. 490 BC). With minor variations Greek drama from that time continues to be performed today .

The city-state of Athens, which became the predominant cultural, political, and military power during this period, was the theater center, where theater was institutionalised as part of a festival called the Dionysia, which honoured the god Dionysus. Tragedy (late 500 BC), comedy (490 BC), and the satyr play were the three dramatic genres to emerge in Athens. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies and allies in order to promote a common cultural identity.

Table of Contents

0 Introduction: Theater in Ancient Greece

1 Theatre of ancient Greece

2 Classical Drama and Society

3 Greek Tragedy

4 Ancient Greek Comedy

5 Satyr Play

Phylax Play

6 Theater Structures

7 Theater of Dionysus, Athens

8 Odeon

0 Introduction: Theater in Ancient Greece

From The Metropolitan Museum of Art: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/thtr/hd_thtr.htm

1 Theatre of ancient Greece

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatre_of_ancient_Greece

The Ancient Greek drama, is a theatrical culture that flourished in ancient Greece from c. 700 BC. The city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and military power during this period, was its centre, where it was institutionalised as part of a festival called the Dionysia, which honoured the god Dionysus. Tragedy (late 500 BC), comedy (490 BC), and the satyr play were the three dramatic genres to emerge there. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies and allies in order to promote a common cultural identity.

Contents

Etymology

The word τραγῳδια (tragoidia), from which the word "tragedy" is derived, is a compound of two Greek words: τράγος (tragos) or "goat" and ᾠδή (ode) meaning "song", from ἀείδειν (aeidein), "to sing".[1] This etymology indicates a link with the practices of the ancient Dionysian cults. It is impossible, however, to know with certainty how these fertility rituals became the basis for tragedy and comedy.[2]

Origins

Main article: Greek tragedyPanoramic view of the theatre at Epidaurus.The classical Greeks highly valued the power of spoken word, and so it was their main method of communication and storytelling. Bahn and Bahn write, "To Greeks the spoken word was a living thing and infinitely preferable to the dead symbols of a written language." Socrates himself believed that once something was written down, it lost its ability for change and growth. For these reasons, among many others, oral storytelling flourished in Greece.[3]

Greek tragedy as we know it was created in Athens around the time of 532 BC, when Thespis was the earliest recorded actor. Being a winner of the first theatrical contest held at Athens, he was the exarchon, or leader,[4] of the dithyrambs performed in and around Attica, especially at the rural Dionysia. By Thespis' time the dithyramb had evolved far away from its cult roots. Under the influence of heroic epic, Doric choral lyric and the innovations of the poet Arion, it had become a narrative, ballad-like genre. Because of these, Thespis is often called the "Father of Tragedy"; however, his importance is disputed, and Thespis is sometimes listed as late as 16th in the chronological order of Greek tragedians; the statesman Solon, for example, is credited with creating poems in which characters speak with their own voice, and spoken performances of Homer's epics by rhapsodes were popular in festivals prior to 534 BC.[5] Thus, Thespis's true contribution to drama is unclear at best, but his name has been immortalized as a common term for performer—a "thespian."

The dramatic performances were important to the Athenians – this is made clear by the creation of a tragedy competition and festival in the City Dionysia. This was organized possibly to foster loyalty among the tribes of Attica (recently created by Cleisthenes). The festival was created roughly around 508 BC. While no drama texts exist from the sixth century BC, we do know the names of three competitors besides Thespis: Choerilus, Pratinas, and Phrynichus. Each is credited with different innovations in the field.

More is known about Phrynichus. He won his first competition between 511 BC and 508 BC. He produced tragedies on themes and subjects later exploited in the golden age such as the Danaids, Phoenician Women and Alcestis. He was the first poet we know of to use a historical subject – his Fall of Miletus, produced in 493-2, chronicled the fate of the town of Miletus after it was conquered by the Persians. Herodotus reports that "the Athenians made clear their deep grief for the taking of Miletus in many ways, but especially in this: when Phrynichus wrote a play entitled "The Fall of Miletus" and produced it, the whole theatre fell to weeping; they fined Phrynichus a thousand drachmas for bringing to mind a calamity that affected them so personally, and forbade the performance of that play forever."[6] He is also thought to be the first to use female characters (though not female performers).[7]

Until the Hellenistic period, all tragedies were unique pieces written in honour of Dionysus and played only once, so that today we primarily have the pieces that were still remembered well enough to have been repeated when the repetition of old tragedies became fashionable (the accidents of survival, as well as the subjective tastes of the Hellenistic librarians later in Greek history, also played a role in what survived from this period).

New inventions during the Classical Period

Theater of Dionysius, Athens, Greece. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival CollectionAfter the Great Destruction of Athens by the Persian Empire in 480 BC, the town and acropolis were rebuilt, and theatre became formalized and an even greater part of Athenian culture and civic pride. This century is normally regarded as the Golden Age of Greek drama. The centre-piece of the annual Dionysia, which took place once in winter and once in spring, was a competition between three tragic playwrights at the Theatre of Dionysus. Each submitted three tragedies, plus a satyr play (a comic, burlesque version of a mythological subject). Beginning in a first competition in 486 BC each playwright submitted a comedy.[8] Aristotle claimed that Aeschylus added the second actor (deuteragonist), and that Sophocles introduced the third (tritagonist). Apparently the Greek playwrights never used more than three actors based on what is known about Greek theatre.[9]

Tragedy and comedy were viewed as completely separate genres, and no plays ever merged aspects of the two. Satyr plays dealt with the mythological subject matter of the tragedies, but in a purely comedic manner.

Hellenistic period

Roman, Republican or Early Imperial, Relief of a seated poet (Menander) with masks of New Comedy, 1st century B.C. – early 1st century A.D., Princeton University Art MuseumThe power of Athens declined following its defeat in the Peloponnesian War against the Spartans. From that time on, the theatre started performing old tragedies again. Although its theatrical traditions seem to have lost their vitality, Greek theatre continued into the Hellenistic period (the period following Alexander the Great's conquests in the fourth century BC). However, the primary Hellenistic theatrical form was not tragedy but 'New Comedy', comic episodes about the lives of ordinary citizens. The only extant playwright from the period is Menander. One of New Comedy's most important contributions was its influence on Roman comedy, an influence that can be seen in the surviving works of Plautus and Terence.

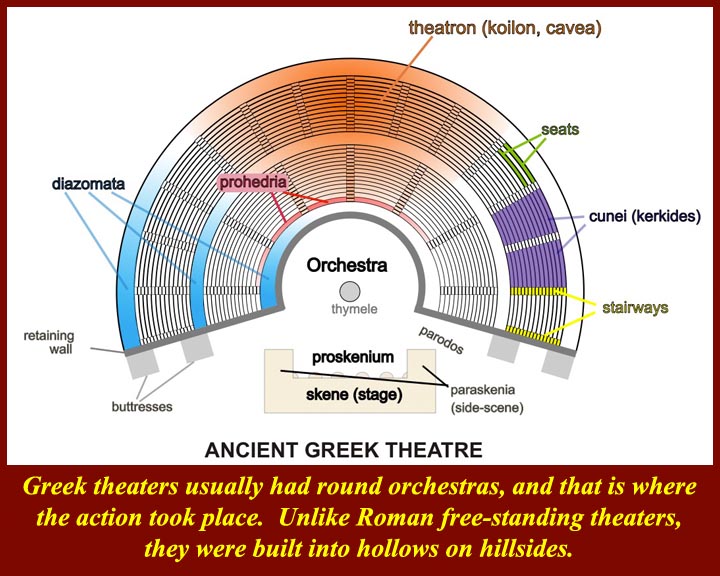

Characteristics of the buildings

The Ancient Theatre of Delphi.The plays had a chorus from 12 to 15[10] people, who performed the plays in verse accompanied by music, beginning in the morning and lasting until the evening. The performance space was a simple circular space, the orchestra, where the chorus danced and sang. The orchestra, which had an average diameter of 78 feet, was situated on a flattened terrace at the foot of a hill, the slope of which produced a natural theatron, literally "watching place". Later, the term "theatre" came to be applied to the whole area of theatron, orchestra, and skené. The coryphaeus was the head chorus member who could enter the story as a character able to interact with the characters of a play.

A drawing of an ancient theatre. Terms are in Greek language and Latin letters.The theatres were originally built on a very large scale to accommodate the large number of people on stage, as well as the large number of people in the audience, up to fourteen thousand. Mathematics played a large role in the construction of these theatres, as their designers had to be able to create acoustics in them such that the actors' voices could be heard throughout the theatre, including the very top row of seats. The Greeks' understanding of acoustics compares very favourably with the current state of the art. The first seats in Greek theatres (other than just sitting on the ground) were wooden, but around 499 BC the practice of inlaying stone blocks into the side of the hill to create permanent, stable seating became more common. They were called the "prohedria" and reserved for priests and a few most respected citizens.

In 465 BC, the playwrights began using a backdrop or scenic wall, which hung or stood behind the orchestra, which also served as an area where actors could change their costumes. It was known as the skênê (from which the word "scene" derives). The death of a character was always heard behind the skênê, for it was considered inappropriate to show a killing in view of the audience.[citation needed] Though there is scholarly argument that death in Greek tragedy was portrayed off stage primarily because of dramatic considerations, and not prudishness or sensitivity of the audience.[11] In 425 BC a stone scene wall, called a paraskenia, became a common supplement to skênê in the theatres. A paraskenia was a long wall with projecting sides, which may have had doorways for entrances and exits. Just behind the paraskenia was the proskenion. The proskenion ("in front of the scene") was beautiful, and was similar to the modern day proscenium.

Greek theatres also had tall arched entrances called parodoi or eisodoi, through which actors and chorus members entered and exited the orchestra. By the end of the 5th century BC, around the time of the Peloponnesian War, the skênê, the back wall, was two stories high. The upper story was called the episkenion. Some theatres also had a raised speaking place on the orchestra called the logeion.

Scenic elements

There were several scenic elements commonly used in Greek theatre:

- mechane, a crane that gave the impression of a flying actor (thus, deus ex machina).

- ekkyklêma, a wheeled platform often used to bring dead characters into view for the audience

- Pinakes, pictures hung to create scenery

- Thyromata, more complex pictures built into the second-level scene (3rd level from ground)

- Phallic props were used for satyr plays, symbolizing fertility in honour of Dionysus.

Masks

Masks

Tragic Comic Masks Hadrian's Villa mosaic.The Ancient Greek term for a mask is prosopon (lit., "face"),[12] and was a significant element in the worship of Dionysus at Athens, likely used in ceremonial rites and celebrations. Most of the evidence comes from only a few vase paintings of the 5th century BC, such as one showing a mask of the god suspended from a tree with decorated robe hanging below it and dancing and the Pronomos vase,[13] which depicts actors preparing for a Satyr play.[14] No physical evidence remains available to us, as the masks were made of organic materials and not considered permanent objects, ultimately being dedicated at the altar of Dionysus after performances. Nevertheless, the mask is known to have been used since the time of Aeschylus and considered to be one of the iconic conventions of classical Greek theatre.[15]

Masks were also made for members of the chorus, who play some part in the action and provide a commentary on the events in which they are caught up. Although there are twelve or fifteen members of the tragic chorus, they all wear the same mask because they are considered to be representing one character.

Mask details

Mask dating from the 4th/3rd century BC, Stoa of AttalosBronze statue of a Greek actor. The half-mask over the eyes and nose identifies the figure as an actor. He wears a man's conical cap but female garments, following the Greek custom of men playing the roles of women. 150-100 BCE.Illustrations of theatrical masks from 5th century display helmet-like masks, covering the entire face and head, with holes for the eyes and a small aperture for the mouth, as well as an integrated wig. These paintings never show actual masks on the actors in performance; they are most often shown being handled by the actors before or after a performance, that liminal space between the audience and the stage, between myth and reality.[14] This demonstrates the way in which the mask was to 'melt' into the face and allow the actor to vanish into the role.[16] Effectively, the mask transformed the actor as much as memorization of the text. Therefore, performance in ancient Greece did not distinguish the masked actor from the theatrical character.

The mask-makers were called skeuopoios or "maker of the properties," thus suggesting that their role encompassed multiple duties and tasks. The masks were most likely made out of light weight, organic materials like stiffened linen, leather, wood, or cork, with the wig consisting of human or animal hair.[17] Due to the visual restrictions imposed by these masks, it was imperative that the actors hear in order to orient and balance themselves. Thus, it is believed that the ears were covered by substantial amounts of hair and not the helmet-mask itself. The mouth opening was relatively small, preventing the mouth to be seen during performances. Vervain and Wiles posit that this small size discourages the idea that the mask functioned as a megaphone, as originally presented in the 1960s.[14] Greek mask-maker, Thanos Vovolis, suggests that the mask serves as a resonator for the head, thus enhancing vocal acoustics and altering its quality. This leads to increased energy and presence, allowing for the more complete metamorphosis of the actor into his character.[18]

Mask functions

In a large open-air theatre, like the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, the classical masks were able to create a sense of dread in the audience creating large scale panic, especially since they had intensely exaggerated facial features and expressions.[18] They enabled an actor to appear and reappear in several different roles, thus preventing the audience from identifying the actor to one specific character. Their variations help the audience to distinguish sex, age, and social status, in addition to revealing a change in a particular character's appearance, e.g. Oedipus after blinding himself.[19] Unique masks were also created for specific characters and events in a play, such as The Furies in Aeschylus' Eumenides and Pentheus and Cadmus in Euripides' The Bacchae. Worn by the chorus, the masks created a sense of unity and uniformity, while representing a multi-voiced persona or single organism and simultaneously encouraged interdependency and a heightened sensitivity between each individual of the group. Only 2-3 actors were allowed on the stage at one time, and masks permitted quick transitions from one character to another. There were only male actors, but masks allowed them to play female characters.

Other costume details

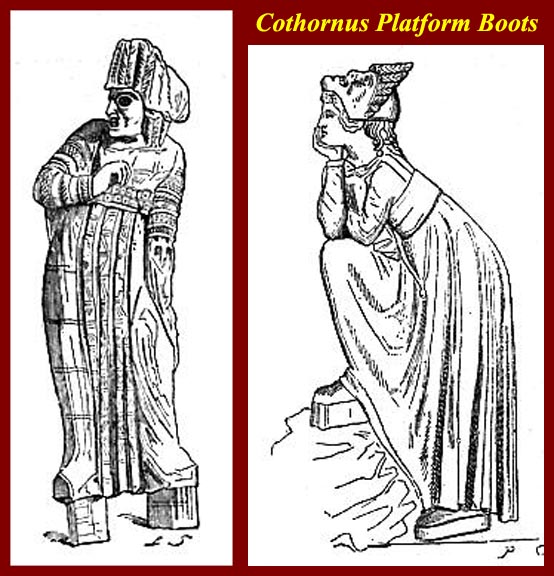

The actors in these plays that had tragic roles wore boots called cothurni that elevated them above the other actors. The actors with comedic roles only wore a thin soled shoe called a sock. For this reason, dramatic art is sometimes alluded to as "Sock and Buskin".

Melpomene is the muse of tragedy and is often depicted holding the tragic mask and wearing cothurni. Thalia is the muse of comedy and is similarly associated with the mask of comedy and the comedic "socks".

See also

- List of ancient Greek playwrights

- List of ancient Greek theatres

- History of theatre

- Representation of women in Athenian tragedy

- Agôn

- Ancient Greek comedy

- Archon

- Aulos

- Buskin

- Chorêgos

- Chorus

- Chorus of the elderly in classical Greek drama

- Comedy

- Coryphaeus

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Didascaliae

- Didaskalos

- Dionysia festivals

- Dithyramb

- Eisodos

- Ekkyklêma

- Episode

- Epode

- Kommós

- Mêchanê

- Melpomene

- Monody

- Ode

- Onomastì komodèin

- Orchêstra

- Parabasis

- Párodos

- Phlyax play

- Protagonist

- Rhapsode

- Satyr play

- Skênê

- Sparagmos

- Stásimon

- Stichomythia

- Strophê

- Thalia (Muse)

- Theatre of ancient Rome

- Theatre of Dionysus

- Theoric fund

- Thespis

- Tragedy

- Tritagonist

- List of films based on Greek drama

Further reading

- Buckham, Philip Wentworth, Theatre of the Greeks, London 1827.

- Davidson, J.A., Literature and Literacy in Ancient Greece, Part 1, Phoenix, 16, 1962, pp. 141–56.

- Davidson, J.A., Peisistratus and Homer, TAPA, 86, 1955, pp. 1–21.

- Easterling, P.E. (editor) (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41245-5.

- Easterling, Patricia Elizabeth; Hall, Edith (eds.), Greek and Roman Actors: Aspects of an Ancient Profession, Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-65140-9

- Else, Gerald F.

- Aristotle's Poetics: The Argument, Cambridge, MA 1967.

- The Origins and Early Forms of Greek Tragedy, Cambridge, MA 1965.

- The Origins of ΤΡΑΓΩΙΔΙΑ, Hermes 85, 1957, pp. 17–46.

- Flickinger, Roy Caston, The Greek theater and its drama, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1918

- Freund, Philip, The Birth of Theatre, London: Peter Owen, 2003. ISBN 0-7206-1170-9

- Haigh, A. E., The Attic Theatre, 1907.

- Harsh, Philip Whaley, A handbook of Classical Drama, Stanford University, California, Stanford University Press; London, H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1944.

- Lesky, A. Greek Tragedy, trans. H.A., Frankfurt, London and New York 1965.

- Ley, Graham. A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theatre. University of Chicago, Chicago: 2006

- Ley, Graham. Acting Greek Tragedy. University of Exeter Press, Exeter: 2015

- Loscalzo, Donato, Il pubblico a teatro nella Grecia antica, Roma 2008

- McDonald, Marianne, Walton, J. Michael (editors), The Cambridge companion to Greek and Roman theatre, Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-521-83456-2

- Moulton, Richard Green, The ancient classical drama; a study in literary evolution intended for readers in English and in the original, Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1890.

- Padilla, Mark William (editor), "Rites of Passage in Ancient Greece: Literature, Religion, Society", Bucknell University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8387-5418-X

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur Wallace

- Dithyramb, Tragedy, and Comedy , Oxford 1927.

- The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, Oxford 1946.

- The Dramatic Festivals of Athens, Oxford 1953.

- Rabinowitz, Nancy Sorkin (2008). Greek Tragedy. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4051-2160-6.

- Riu, Xavier, Dionysism and Comedy, 1999. review

- Ross, Stewart. Greek Theatre. Wayland Press, Hove: 1996

- Rozik, Eli, The roots of theatre: rethinking ritual and other theories of origin, Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2002. ISBN 0-87745-817-0

- Schlegel, August Wilhelm, Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, Geneva 1809.

- Sommerstein, Alan H., Greek Drama and Dramatists, Routledge, 2002.

- Sourvinou-Inwood, Christiane, Tragedy and Athenian Religion, Oxford:University Press 2003.

- Tsitsiridis, Stavros, "Greek Mime in the Roman Empire (P.Oxy. 413: Charition and Moicheutria", Logeion 1 (2011) 184-232.

- Wiles, David. Greek Theatre Performance: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 2000

- Wiles, David. The Masks of Menander: Sign and Meaning in Greek and Roman Performance, Cambridge, 1991.

- Wiles, David. Mask and Performance in Greek Tragedy: from ancient festival to modern experimentation, Cambridge, 1997.

- Wise, Jennifer, Dionysus Writes: The Invention of Theatre in Ancient Greece, Ithaca 1998. review

- Zimmerman, B., Greek Tragedy: An Introduction, trans. T. Marier, Baltimore 1991.

References

- Merriam-Webster definition of tragedy

- Ridgeway (1910), p. 83

- Bahn, PhD., Eugene and Margaret L. Bahn (1970). A History of Oral Interpretation. Minneapolis, MN: Burgess Publishing Company. p. 3.

- Aristotle, Poetics

- Brockett (1999), pp. 16–17

- Herodotus, Histories, 6/21

- Brockett (1999), p. 17

- Kuritz (1988), p. 21

- Kuritz (1988), p. 24

- Jansen (2000)

- Pathmanathan (1965)

- Liddell & Scott via Perseus @ UChicago

- Tufts.edu

- Vervain & Wiles (2004), p. 255

- Varakis (2004)

- Vervain & Wiles (2004), p. 256

- Brooke (1962), p. 76

- Vovolis & Zamboulakis (2007)

- Brockett & Ball (2000), p. 70

Bibliography

- Brockett, Oscar G. (1999). History of the Theatre (8th ed.). Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 9780205290260.

- Brockett, Oscar G.; Ball, Robert (2000). The Essential Theatre (7th ed.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace.

- Brooke, Iris (1962). Costume in Greek Classical Drama. London: Methuen.

- Jansen, Jan (2000). Lebensqualität im Theater des demokratischen Athen: Kult, Politik und Alte Komödie [Quality of life in the theatre of Democratic Athens: cults, politics and ancient comedy] (PDF) (in German). Munich, Germany: GRIN. ISBN 9783638291873.

- Kuritz, Paul (1988). The Making of Theatre History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780135478615.

- Pathmanathan, R. Sri (1965). "Death in Greek tragedy". Greece and Rome 12 (1): 2–14. JSTOR 642398.

- Ridgeway, William (1910). Origin of Tragedy with Special Reference to the Greek Tragedians.

- Varakis, Angie (2004). "Research on the Ancient Mask". Didaskalia 6 (1).

- Vervain, Chris; Wiles, David (2004). The Masks of Greek Tragedy as Point of Departure for Modern Performance. New Theatre Quarterly 67. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vovolis, Thanos; Zamboulakis, Giorgos (2007). "The acoustical mask of Greek tragedy". Didaskalia 7 (1).

External links

Wikisource has original works on the topic: Theatre of ancient Greece

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Greek theatre.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greek and Roman theatre masks.

- Ancient Greek theatre history and articles

- Drama lesson 1: The ancient Greek theatre

- Ancient Greek Theatre

- The Ancient Theatre Archive, Greek and Roman theatre architecture – Dr. Thomas G. Hines, Department of Theatre, Whitman College

- Greek and Roman theatre glossary

- Illustrated Greek Theater – Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden-Sydney College, Virginia

- Searchable database of monologues for actors from Ancient Greek Theatre

- Logeion: A Journal of Ancient Theatre with free access which publishes original scholarly articles including its reception in modern theatre, literature, cinema and the other art forms and media, as well as its relation to the theatre of other periods and geographical regions.

2 Classical Drama and Society:

If you really want to delve deep, course materials From USU Clas 3160:

Chapters and Readings, http://www.usu.edu/markdamen/ClasDram/chapters/indexchapters.htm

and Play Reviews, http://www.usu.edu/markdamen/ClasDram/playreviews/playreviews.htm

Chapters and Readings

Click on any of the links below to access the Chapters and Readings.

Play Reviews

The links below take you to surveys of the surviving plays written by the major ancient playwrights who have works preserved entire.

3 Greek Tragedy

Thespis of Icaria - 6th century BC: first actor

(whence Thespians).

Supposedly won the first Dionysia in Athens.

Plays attributed to him are considered forgeries.

Aeschyl us, c 525/4 - c 456/5 BC

The Persians - 472 BC

Seven Against Thebes - 467 BC

The Suppliants - 463 BC

Oresteia (only surviving trilogy) - 458 BC

Agamemnon,

Libation Bearers,

Eumenedes

Prometheus Bound - 480s(?) through 410s?

(debated attribution - perhaps by

Euphorion, son of Aeschylus)

Plus at least 71 lost plays

Sophocles, c.497/6 - winter 406/5 BC

Theban plays _(pseudo-trilogy)

Oedipus Rex

Oedipus at Colonus

Antigone

Ajax - c.450 - 430 BC (?)

Women of Trachis - c. 450 through c. 425

(various scholars)

Electra - last decade of 5th century BC(?)

Philoctetes - 409 BC

Plus at least 80 lost plays

Euripides, c. 480 - 406 BC

Nineteen extant Plays (Chart)

Plus 73 -76 lost and fragmentary plays

4 Ancient Greek Comedy

Periods:

Old Comedy (archaia)

Aristophanes

Works of Aristophanes

Known Dramatists

Middle Comedy (mese)

No complete plays survive

Known Dramatists (No known dominant

dramatist)

New Comedy (nea) - Hellenistic Period -- introduced stock

characters

Dramatists:

Menander, c. 342/41 - c. 290 BC

More complete Plays (no full texts have

been found.)

Only ragments available

Philemon, c. 362 - c. 262

Of 97 works, 57 are known from titles

and fragments.

Emporos and Thesauros adapted in

Latin by Plautus as Mercator and

Trinummus

Diphilus, contemporary of Menander

Of perhaps 100 works, 54 are known

from titles and fragments.

Plautus also adapted some works of

Diphilus: e.g., Kleroumenoi became

Casina, Onagos became Asinaria, etc.

[A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the

Forum, a Sondheim/Shevelove/Gelbert

Broadway musical was inspired by the farces

of Plautus, specifically Pseudolus, Miles

Gloriosus and Mostellaria all of which were

adapted from Greek New Comedy.]

5 Satyr Play - The fourth play submitted with a tragic trilogy

Everyone who wrote tragedies also wrote Satyr plays.

Satyr plays were an ancient Greek form of tragicomedy, similar in spirit to the bawdy satire of burlesque. They featured choruses of satyrs, were based on Greek mythology, and were rife with mock drunkenness, brazen sexuality (including phallic props), pranks, sight gags, and general merriment.

Arion - Semi-mythical Choral Dithyramb creator

(c. 600 BC): choruses of 50 circle-dancers dressed

as satyrsa

Pratinas - Satyr play innovator c. 500 BC

Euripides: Cyclops, the only complete satyr play

that survived antiquity. Full English text

Phylax Play (AKA hilarotragedy, AKA Rhintonic Plays) sub-genre of Satyr.

Flourished in Magna Graecia - 4th century BC and after.

Mixed Greek gods with New Comedy stock characters.

Rhinthon of Tarentum - apparent inventor of the sub-genre, wrote 38

plays, only titles of some are known along with a few lines quoted

by others.

Other (only 4) known Phylax authors:

Sciras (AKA Sclerias) of Tarentum -- fragments quoted by others.

Title of one play, Meleager, is known.

Blaesus of Capri -- Mesotribas and Satournosis quoted by Athenaeus.

Sopator of Paphos -- name known only (Not the same as the

companion of Paul).

Heraklides -- name known only.

Phylax plays greatly influence Roman comedy.

A substantial body of South Italian vases are thought to represent scenes

of the phlyakes

6 Greek Theater Structures

Physical Structure and Stagecraft of Classical Greek Theater

From https://shshonorsenglish10.wikispaces.com/Physical+Structure+and+Stagecraft+of+Classical+Greek+Theater

Ancient Greek theaters were very large, open, and took advantage of hillsides for their seating. They were also built in city centers or any place where people could watch the story being acted out unfold. Every theater had the same basic structure.

PARTS OF THE THEATRE

Theatron

The large seating area or theatron ("viewing place") is built into the side of a hill and partially surrounds the orchestra, similar to a stadium today. People usually sat on cushions or boards, but eventually sat on marble seats.

Orchestra

The core of any Greek theater is the orchestra ("dancing space"). It was a flat, circular space where the dancers and actors would interact. There was often an altar built in the center. The earliest orchestras had dirt floors, as the theater developed, orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials.

Greek Orchestr Skene

The skene ("tent") was a building behind the orchestra where actors could make entrances, exits, and even climb up on the roof. It was decorated to fit the setting of the play, equivalent to the modern-day backstage and set.

Parados

A parados ("passageway") was a path near the stage. Paradoi were corridors through which actors and chorus members could make entrances and exits. The audience also used them to come and go before and after performances.

Proskenion

The proskenion ("in front of the skene") was a rectangular acting area in front of the skene. The proskenion was either on ground level or raised, depending on the time period. It was also called the okribas.

Development of the Greek Theater

The Greek theater was originally comprised of a circular orchestra loosely connected to a separate rectangular skene. However, as the theater evolved, a proskenion was stretched between the paraskenion (side stages) off the skene and cut into the circle. This new semicircular structure helped unite the theatron to the theater.

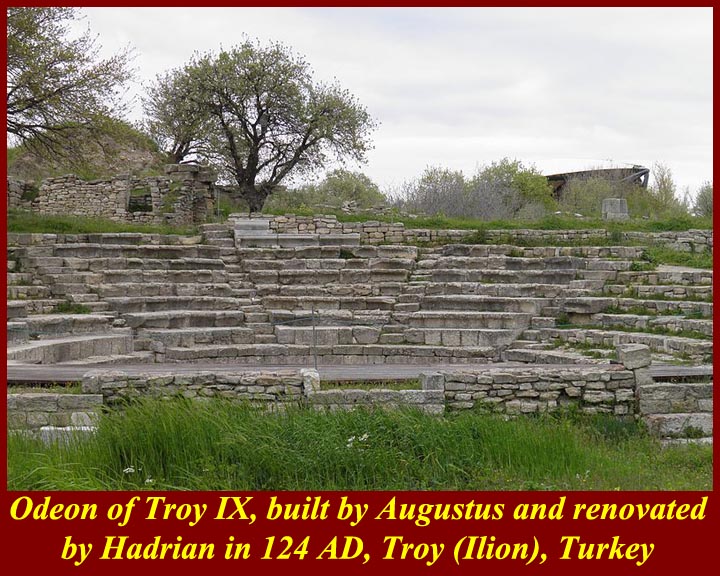

Indoor theatres

There were a few indoor theatres that were used for musical performances and particular types of tragedies. These were called Odeions.

Machines

The Aeorema was a crane that was used to transport the gods into and out of the scenes. The Periactoi were two pyramid shaped pillars that were positioned on the left and right side of the skene. When the pivoted, it helped change the background of the scene. The Ekeclema was a wheeled platform on which dead bodies were presented to the audience. A murder or suicide was never performed in front of the crowd.

SIGNIFICANT GREEK THEATER

Dodoni

Dodoni was a special place in ancient greek and it remains special to this date.The sanctuary of Dodoni was as spiritual place in ancient Greece. It was the oldest of the Greek oracles.

Epidaurus

Epidaurus was built round the 3d Century BC and it is adorned with a multitude of buildings most famous of which is the ancient Theater of Epidaurus. It was a healing center as well as a cultural center in ancient times.This is one of the very few theaters that retains its original circular "Orchestra" and it is a rear aesthetic sight. The theater is still in use today with frequent plays, concerts, and festivals.

The Theatre of Dionysus

The theater was built into the south slope of the Acropolis. It was the first theater in the world to be built of stone, it was also the first theater to perform a tragedy. The theater was built in stages and could seat 17,000 spectators.

Athens acropolis from the Theater of Dionysus

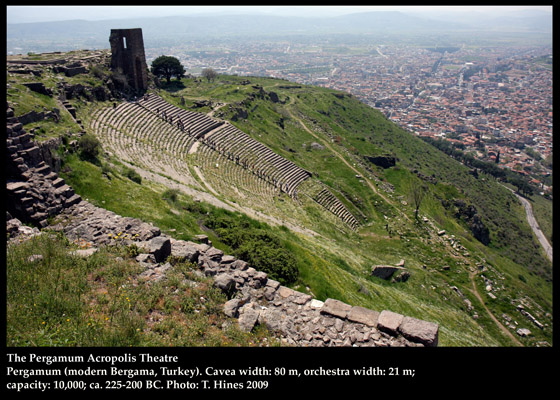

Pergamum Theatre

This theatre located in modern-day Turkey was the steepest theater in the ancient world. The seats extended 122 feet above the orchestra.

==

==

WHAT WOULD YOU SEE IN THE THEATRE?

Ancient Greek theater was a "... mixture of myth, legend, philosophy,

social commentary, poetry, dance, music, public participation, and visual splendor." (Cohen 64)

Costumes

Cothornus (A calf-length, loose-fitting platform boot, often with upturned toes, which by 460 bc had become a standard feature of tragic costume.)

Cothurnus boots played a very important role in Ancient Greek theatre. As Ancient Greek theatre developed, so did the cothurnus. They become more decorative and the lengths of the tops of the boots started to become more varied. Usually, the most powerful man would be wearing cothurnus, or at least the nicest pair of cothurnus. The boots were also different heights. The taller the character in the play, the more important he was. Corthurnus are the first shoes with modern day “lifts”.

Masks

Masks were the most important element of the costumes. These huge masks could usually be seen from the very back of the theatre. Masks were overly dramatic and showed the emotion of the actor. Because the number of actors varied from one to three, they had to put on different masks in order to play more roles.The actors were all men so the mask was therefore necessary to let them play the female roles. Usually the masks were made of linen, wood, or leather. A marble or stone face was used as a mould for the mask. Human or animal hair was also used. The eyes were fully drawn but in the place of the pupil of the eye was a small hole so that the actor could see. The shape of the masks helped amplify the actors voice making it easier for the audience to hear them in the back of the theatre.

Chorus

The chorus was very important to the plot of the play. Without the chorus the audience would be confused, as the chorus is the main narrator of the story line. The choregos was kind of the head of the chorus and paid all the expenses including masks, music, costumes, and any other production items. The size ranged from 12-15 people depending on the type of play [as many as fifty for grand productions -- tkw]. Also, the name of the chorus changed for the different types of play. In a tragedy, the chorus was solemn and called "emmelia." In a comedy, it was funny and called "codrax." In a satyric drama, it was scoptic and called "sicinnis."

Actors

The cast of a Greek play were amateurs, not professionals. All males. Actors had to gesture grandly so that the entire audience could see and hear the story. Since the cast was all men they had to come up with costumes that portrayed them as women. In order to have a female appearance, they wore a "prosternida" (before the chest, imitating a woman's breasts) and the "progastrida" before the belly.

Special Effects

Deus ex Machina

Deus ex Machina, the "God from the Machine", was often used in Greek drama. Many times, a god would rescue the hero when they were in an impossible situation. A crane-like machine involving pulleys and wires would lower the god onto the stage, and the character would be saved. Today, when a playwright ends with an happy or convenient conclusion it is often frowned upon. It might be fine for a comedy, but in serious works of drama, most critics and audience members want to see the protagonist succeed or fail.

For example, In Medea, Euripides uses Deus ex Machina when Medea is rescued by a dragon-drawn chariot.

GREEK PEOPLE AND THE THEATRE

Preferential Seating

The preferred seats or Proedria were usually given to priests, magistrates and other dignitaries. The middle seat in the front row was usually reserved for the high priest or a position of matching authority. It was the most sought after seat in the theatre and was usually inscribed with the title of the person in the position. There was also seats blocked off for members of the boule, or the 500 member Executive Council of the Assembly.

Theatre Tickets

Tickets today haven't changed much from the Greek era. On the ticket would be a letter which referred to a specific row of seats. The price of a theatre ticket was about 2 obols, equal to a day's work of an unskilled laborer. Athens had a special fund for citizens that could not afford the tickets. Those who enrolled could receive the money for a ticket. This Theoric Fund shows the focus that was put on attending the theatre.

References

- http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110tech/theater.html

- http://www.whitman.edu/theatre/theatretour/glossary/glossary.htm

- Greek Architecture by Robert L. Scranton

- http://www.greeklandscapes.com/greece/ancient_theaters.html

- http://www.richeast.org/htwm/Greeks/theatre/Theatre.html

- http://www.fashionencyclopedia.com/fashion_costume_culture/The-Ancient-World-Rome/Cothurnus.html

- http://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~jlynch/Terms/deusexmachina.html

- http://plays.about.com/od/playwritingbusiness/qt/exmachina.htm

- The Art of Ancient Greek Theater by Mary Louise Hart

Bibliography

- Ancient Greek Theatre. Web. 02 Oct. 2011.

- <http://www.greektheatre.gr/constr.html>

- "ANCIENT GREEK THEATRE." Web. 02 Oct. 2011.

- http://www.richeast.org/htwm/Greeks/theatre/Theatre.html.

- Bradford, Wade. "Deus Ex Machina - God From the Machine - Lazy Conclusions and

- Resolutions." Plays / Drama. About.com, 2011. Web. 02 Oct. 2011.

- http://plays.about.com/od/playwritingbusiness/qt/exmachina.htm.

- "Cothurnus - Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages." Contemporary Fashion. Web. 02 Oct. 2011. <http://www.fashionencyclopedia.com/fashion_costume_culture/The-Ancient-World-Rome/Cothurnus.html>.

- "Greek Theater." Reed College. Web. 02 Oct. 2011.

- http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110tech/theater.html.

- Lynch, Jack. "Lynch, Literary Terms — Deus Ex Machina." Rutgers-Newark: The State

- University of New Jersey. Web. 02 Oct. 2011. <http://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~jlynch/Terms/deusexmachina.html>.

- Scranton, Robert L. Greek Architecture. New York: G. Braziller, 1962. Print.

- "The Theater of Dionysus." Grisel's Home Page. Web. 02 Oct. 2011.

- <http://www.grisel.net/dionysus.htm>.

7 Theater of Dionysus, Athens

Present-day remains of the Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus, AthensThe Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus is a major open-air theatre and one of the earliest preserved in Athens.It is considered the first theatre in the world. It was used for festivals in honor of the god Dionysus. Greek theaters in antiquity were in many instances of huge proportions but, under ideal conditions of occupancy and weather, the acoustical properties approach perfection by modern test. We know that the theater of Dionysus in Athens could seat 17,000 spectators, and that the theater in Epidaurus can still accommodate 14,000.[1] It is sometimes confused with the later and better-preserved Odeon of Herodes Atticus, located nearby on the southwest slope of the Acropolis. Some believed that Dionysus himself was responsible for its construction.

The South slope of the Acropolis has two theaters, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus and the Theater of Dionysos. The Theater of Dionysos is not as well preserved as the other, but it has more significance. The structure dates back to the fourth century BC but had many other later remodelings. The Athenian tradition of theatrical representations first began at the Theatre of Dionysos. Theater developed into a religious celebration, in honor of the god Dionysos. Theatrical performances were actually competitions. The winners received monuments to display the tripods they had won. The monument that displayed the winners’ tripod would be placed around the theater and along a street that led East; the Street of the Tripods.[2]

Contents

History

The site of the Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus, on the south slope of the Athenian Acropolis, has been known since the 1700s. The Greek Archaeological Society excavated the remains of the theatre beginning in 1838 and throughout most of the 19th century. Early remains in the area relating to the cult of Dionysus Eleuthereus have been dated to the 6th century BCE, during the rule of Peisistratus and his successors, but a theatre was apparently not built on the site until a century later. The only certain evidence of this early theatre consists of a few stone blocks that were reused in the fourth century BCE.[3]

During the sixth century BCE, performances associated with the festivals of Dionysus were probably held in the Athenian agora, with spectators seated on wooden bleachers (ikria) set up around a flat circular area, the orchestra, until the ikria collapsed in the early fifth century BCE, an event attested in ancient sources. After the collapse of the stands, the dramatic and musical contests were moved to the precinct of Dionysus on the slope of the Acropolis.

Marble thrones in the prohedria of the Theatre of DionysusAlterations to the stage were made in the subsequent The early theatre must have been very simple, comprising a flat orchestra, with a few rows of wooden or stone benches set into the hill. The oldest orchestra in the theatre precinct is thought to have been circular (or nearly so) with a diameter of around 27 metres, although there is some debate as to its original size and shape.[4] A wooden scene building (skene) was apparently introduced at the back of the orchestra, serving for the display of artificial scenery and perhaps to enhance the acoustics.[5] It was in this unpretentious setting that the plays of the great fifth century BCE Attic tragedians were performed.

By the end of the fifth century BCE, some of the wooden constructions had been replaced with stone.[6] The Theatre of Dionysus in its present general state dates largely to the period of the Athenian statesman Lycurgus (ca. 390-325/4 BCE), who, as overseer of the city's finances and building program, refurbished the theatre in stone in monumental form. The fourth century theatre had a permanent stage extending in front of the orchestra and a three-tiered seating area (theatron) that stretched up the slope. The scene building had projecting wings at both ends (paraskenia), which might have accommodated stairways or movable scenery.[7] According to Margarete Bieber, the earliest stone skene with remains surviving is that of the Theatre of Dionysus.[8]

Hellenistic period, and 67 marble thrones were added around the periphery of the orchestra, inscribed with the names of the dignitaries that occupied them. The marble thrones that can be seen today in the theatre take the form of klismos chairs, and are thought to be Roman copies of earlier versions.[9] At the center of this row of seats was a grand marble throne reserved for the priest of Dionysus.

The Theatre of Dionysus underwent a modernization in the Roman period, although the Greek theatre retained much of its integrity and general form. An entirely new stage was built in the first century CE, dedicated to Dionysus and the Roman emperor Nero. By this time, the floor of the orchestra had been paved with marble slabs, and new seats of honor were constructed around the edge of the orchestra. Late alterations carried out in the third century CE by the archon Phaedrus included the re-use of earlier Hadrianic reliefs, which were built into the front of the stage building.[10] The remains of a restored and redesigned Roman version of the theatre can still be seen at the site today.

Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus, Athens, Roman stage building with re-used reliefsThe theatre was dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine and the patron of drama; it hosted the City Dionysia festival. Among those who competed were the dramatists of the classical era whose works have survived: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, and Menander. The advent of tragedy, in particular, is credited to the Athenians with festivals staged during specific times of year. These dramatic festivals were competitive among playwrights and involved the production of four plays, three tragedies and one satyr play featuring lighter themes. Early on, the subject matter of the four plays was often linked, with the three tragedies forming a trilogy, such as the Oresteia of Aeschylus. This famous trilogy (Agamemnon, Choephori, and Eumenides) won the competition of 458 BCE held in the Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus. The plays tell the story of the curse on the House of Atreus: Agamemnon’s murder by his wife, the revenge of their son, Orestes, upon his mother, and Orestes’ trial in Athens.

By the time of the Oresteia, dramatists would have had a skene and probably also a wheeled platform for special effects (ekkyklema) and a lifting device (mechane) available for their productions, as well as the use of a third actor. In the late fourth century exaggerated masks were worn and considered highly important for character identification to an audience consisting of thousands.[11] It is assumed that earlier masks, such as those worn in plays by Aeschylus, were more modest in expression and size.[12] With all this in mind, one can perhaps form an impression of the ancient Theatre of Dionysus and appreciate the context of the dramatic performances that took place there.

The Theatre of Dionysus also sometimes hosted meetings of the Athenian Ekklesia after the Pnyx was deemed unsuitable. In the Roman period, "crude Roman amusements" that were ordinarily restricted to the amphitheatre replaced the sacred performances once held in the theatre, and by the Byzantine period, the entire complex had been destroyed.[13]

Restoration

On November 24, 2009 Greek authorities announced that they would partially restore the Theatre of Dionysus. The Culture Ministry said the nine million program is set for completion by 2015.[14][15]

References

- Henry C. Montgomery, "Amplification and High Fidelity in the Greek Theater". The Classical Journal. Vol. 54, No. 6. (March 1959). Pages 242-245. www.jstor/stable/3294133

- Charles Gates, Ancient Cities, (New York: Routledge, 2011), 263-264.

- Travlos 1971 p. 537.

- Bieber 1961 pp. 54-55, 63; Travlos 1971 p. 537.

- Dinsmoor 1950 p. 208.

- Dinsmoor pp. 208-209.

- Dinsmoor pp. 246-249.

- Bieber p. 67.

- Bieber pp. 70-71; Dinsmoor p. 318; Richter 1966 p. 37, fig. 197.

- Travlos p. 538; Bieber pp. 214-215, figs. 53-55.

- Brooke 2003 p. 75.

- Brooke 2003 p. 78.

- Bieber 1961 p. 216; Travlos 1971 p. 538.

- "2,500-year-old Greek theatre under the Acropolis to be restored", The Guardian (UK), Wednesday 25 November 2009

- "Acropolis South Side", Athens Information Guide

Sources

- Bieber, Margarete. The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961.

- Brooke, Iris. Costume in Greek Classic Drama. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 2003.

- Brown, Andrew. "Ancient Greece." In The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Ed. Martin Banham, 441-447. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998.

- Brockett, Oscar G. and Franklin J. Hildy. History of the Theatre. Ninth edition, International edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003.

- Camp, John M. The Archaeology of Athens. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Dinsmoor, William Bell. The Architecture of Ancient Greece. London and Sydney: B. T. Batsford, 1950.

- Flickinger, Roy Caston, The Greek theatre and its drama, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1918.

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. The Athenian Acropolis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Kopff, E. Christian (1997). Ancient Greek Authors. Gale. ISBN 978-0-8103-9939-6.

- Rehm, Rush. Greek Tragic Theatre. New York: Routledge, 1994.

- Rehm, Rush. Greek Tragic Theatre. Theatre Production Studies ser. London and New York: Routledge, 1992.

- Richter, G. M. A. The Furniture of the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans. London: Phaidon Press, 1966.

- Travlos, John. Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens. London: Thames and Hudson, 1971.

Further reading

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur Wallace

- Dithyramb, Tragedy, and Comedy , Oxford 1927.

- The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, Oxford 1946.

- The Dramatic Festivals of Athens, Oxford 1953.

- Rabinowitz, Nancy Sorkin (2008). Greek Tragedy. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-1-4051-2160-6. This contains an exposition and treatment of the Theatre of Dionysus.

- Rozik, Eli, The Roots of Theatre: Rethinking Ritual and Other Theories of Origin, Iowa City : University of Iowa Press, 2002.

External links

- Media related to Theatre of Dionysus at Wikimedia Commons

8 OdeonFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odeon_%28building%29

with additional images

Odeon is the name for several ancient Greek and Roman buildings built for music: singing exercises, musical shows, poetry competitions, and the like. The word comes from the Ancient Greek ᾨδεῖον, Ōideion, literally "singing place", or "building for musical competitions"; from the verb ἀείδω, aeidō, "I sing", which is also the root of ᾠδή, ōidē, "ode", and of ἀοιδός, aoidos, "singer".

Contents

Description

In a general way its construction was similar to that of an ancient Greek theatre, but it was only a quarter of the size and was provided with a roof for acoustic purposes, a characteristic difference. The prototype odeon was the Odeon of Pericles (Odeon of Athens), a mainly wooden building by the southern slope of the Acropolis of Athens. It was described by Plutarch as 'many-seated and many-columned' and may have been square, though excavations have also suggested a different shape, 208 x 62 feet. It was said to be decorated with the masts and spars of ships captured from the Persians. It was rebuilt by king Ariobarzanes after destruction by fire in the Mithridatic war.[1]

Examples

The oldest known odeon in Greece was the Skias at Sparta, so called from its resemblance to the top of a parasol, said to have been erected by Theodorus of Samos (600 B.C.); in Athens an odeon near the spring Enneacrunus on the Ilissus was referred to the age of Peisistratus, and appears to have been rebuilt or restored by Lycurgus (c. 330 B.C.). This is probably the building which, according to Aristophanes,[2] was used for judicial purposes, for the distribution of corn, and even for the billeting of soldiers.

The most magnificent odeon was the Odeon of Herodes Atticus on the southwest cliff of the Acropolis at Athens. It was built in about 160 A.D. by the wealthy sophist and rhetorician Herodes Atticus in memory of his wife, and considerable remains of the odeon still exist. It had accommodation for 8000 persons, and the ceiling was constructed of beautifully carved beams of cedar wood, probably with an open space in the centre to admit the

light. It was also profusely decorated with pictures and other works of art.

Herodus Atticus Odeon, Athens -- now an open air theater (unroofed) seating about 8000. Seating and the stage have been redone, and the odeon is now used for theater and concert festivals.

Similar buildings also existed in other parts of Greece; at Corinth, also the gift of Herodes Atticus; at Patrae, where there was a famous statue of Apollo; at Smyrna, Tralles, and other towns in Asia Minor.

The first odeon in Rome was built by Domitian, a second by Trajan.

Notes

- Oxford Classical Dictionary (First ed.). OUP. p. 617.

- Wasps, 1109.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Odeum". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Odeon of Athens

Site plan of the Acropolis at Athens showing the major archaeological remains – the Odeon is number 19, on the far rightThe Odeon of Pericles By the THEATRON consortium http://www.didaskalia.net/studyarea/visual_resources/pericles3d.html

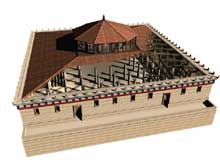

The Odeon of Pericles, situated next to the Theatre of Dionysus, on the south slope of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Although no longer standing, recent excavations have revealed the exact site of the Odeon to be the south-eastern corner of the Acropolis, on the sacred Dionysian precinct. The Odeon is believed to have been the first roofed theatre-building devoted to performance, as well as the first permanent theatre built on the south slope.The Odeon was constructed between 446-442 BC. Built mainly from timber, the Odeon is believed to have stood for over three centuries, before being destroyed by fire and later rebuilt using stone. The Odeon of Pericles was regarded as being one of the finest architectural wonders of ancient Athens.

The Odeon was used for theatrical performances and poetry readings, and probably accommodated political and philosophical lectures. The Odeon also hosted rehearsals for the Lenaean and Panathenaic festivals, as it provided the acting companies with a year-round housed theatre-space, as well as being used as a gathering place for choruses, a store for theatrical props, and a place to stow tributes to the gods, such as the armour of the dead.

(click on the images to expand)

Architectural cut-away View of the interior View of the exterior

Images copyright the University of Warwick. Created by the THEATRON Consortium.

------

and from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odeon_of_Athens

The Odeon of Athens or Odeon of Pericles in Athens was a 4000 m² odeon, built at the south-eastern foot of the Acropolis in Athens, next to the entrance to the Theatre of Dionysus.

Contents

History

It was first built in 435 BC by Pericles for the musical contests that formed part of the Panathenaea,[1] for audiences from the theatre to shelter in case of bad weather and for chorus rehearsals.[2] Few remains of it now survive, but it seems to have been "adorned with stone pillars" (according to Vitruvius and Plutarch) and square instead of the usual circular shape for an odeon. It was covered with timber made from captured Persian ships, culminating in a square pyramid-like roof resembling a tent – Pausanias wrote that the 1st century BC rebuild of it was "said to be a copy of Xerxes' tent", and that might well have applied to the original building.

Plutarch writes that the original building had many seats and many pillars. Modern excavation work has revealed its foundations and it is now known that the roof was supported by 90 internal pillars, in nine rows of ten. From a few other passages, and from the scanty remains of such edifices, we may conclude further that it had an orchestra for the chorus and a stage for the musicians (of less depth than the stage of the theatre), behind which were rooms, which were probably used for keeping the dresses and vessels, and ornaments required for religious processions. It required no shifting scenery but its stage's back-wall seems to have been permanently decorated with paintings. For example, Vitruvius writes[3] that, in the small theatre at Tralleis (which was doubtless an Odeum), Apaturius of Alabanda painted the scaena with a composition so fantastic that he was compelled to remove it, and to correct it according to the truth of natural objects.

The original Odeon of Athens was burned down during Sulla's siege of Athens in the First Mithridatic War in 87–86 BC, either by Sulla himself[4] or by his opponent Aristion for fear that Sulla would use its timbers to storm the Acropolis.[5] It was later fully rebuilt by Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia, using C. and M. Stallius and Menalippus as his architects. The new building was referred to by Pausanias in the 2nd century AD as "the most magnificent of all the structures of the Greeks".[6] He also refers to a "figure of Dionysus worth seeing" in an odeon in Athens,[7] though he does not specify which odeon.

Notes

- Plutarch, Pericles 13

- Vitruv. V.9

- VII.5. § 5

- Geography, 1.20.1

- Appian, Bellum Mithridaticum, 38

- The Family Minstrel, 1 September 1835, p116

- Geography, 1.14.1

References

- Böckh, Corp. Inscr. vol. I No. 357

- William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, London, 1875

Sources

- (Spanish) Diccionario enciclopédico popular ilustrado Salvat (1906–1914)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). "article name needed". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray.

-------

and from http://www.livius.org/ia-in/influence/influence03.html

Architecture: Odeon

It is certain that after Plataea, the pavilion of the great king was taken to Athens. But what happened next? It has been assumed that (a part of) it was already used in 472 as decor [sk�n�] of the tragedy The Persians by Aeschylus. Another and more plausible suggestion -not necessarily contradicting the preceding one- is that the wooden construction was used as a music hall (odeon) and later rebuilt from stone. This can be concluded from the following words by the Greek author Plutarch of Chaeronea:

The Odeon, or music room, which in its interior was full of seats and ranges of pillars, and outside had its roof made to slope and descend from one single point at the top, was constructed, we are told, in imitation of the king of Persia's pavilion [skene]. This was done by Pericles's order.It is not surprising that the pavilion was used as a piece of scenery or/and music room. After all, Athens had been sacked and emergency accommodation and temporary buildings are to be expected. Besides, the pavilion of Xerxes was not a family tent, but a portable palace.[Plutarch, Life of Pericles 13.5-6]

When the Odeon of Pericles was excavated, it turned out to have almost the same dimensions as the Hall of the Hundred Columns at Persepolis, the capital of the Achaemenid empire. The Odeon measured 68,50 x 62,40 meters and contained 9 x 10 columns; the room of the Persepolis palace had -surprise, surprise- 10 x 10 columns and measured 68,50 x 68,50 meters. The similarity is too obvious to be coincidental. The pavilion must have been a copy of the Hall of the Hundred Columns, and the Odeon must have been a copy of this copy.It should be noted, however, that this Persian example was not really followed in Greek and Roman architecture. The acoustics of the Odeon of Pericles must have been terrible. Later odeons, e.g. those of Agrippa, Domitian and Herodes Atticus, were little theaters and not square halls

Odeon of Pericles

Reconstruction of the Hall of Hundred Columns.