For most of us, architecture is easy to take for granted. Its everywhere in our daily lives—sometimes elegant, other times shabby, but generally ubiquitous. How often do we stop to examine and contemplate its form and style? Stopping for that contemplation offers not only the opportunity to understand one’s daily surroundings, but also to appreciate the connection that exists between architectural forms in our own time and those from the past. Architectural tradition and design has the ability to link disparate cultures together over time and space—and this is certainly true of the legacy of architectural forms created by the ancient Greeks.

The Erechtheion,

421-405 B.C.E. (Classical Greek),

Acropolis, Athens, photo: Steven

Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)Greek

architecture refers to the architecture of the

Greek-speaking peoples who inhabited the Greek

mainland and the Peloponnese, the islands of

the Aegean Sea, the Greek colonies in Ionia

(coastal Asia Minor), and Magna Graecia (Greek

colonies in Italy and Sicily). Greek

architecture stretches from c. 900 B.C.E. to

the first century C.E. (with the earliest

extant stone architecture dating to the

seventh century B.C.E.). Greek architecture

influenced Roman architecture and architects

in profound ways, such that Roman Imperial

architecture adopts and incorporates many

Greek elements into its own practice. An

overview of basic building typologies

demonstrates the range and diversity of Greek

architecture.

The Erechtheion,

421-405 B.C.E. (Classical Greek),

Acropolis, Athens, photo: Steven

Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)Greek

architecture refers to the architecture of the

Greek-speaking peoples who inhabited the Greek

mainland and the Peloponnese, the islands of

the Aegean Sea, the Greek colonies in Ionia

(coastal Asia Minor), and Magna Graecia (Greek

colonies in Italy and Sicily). Greek

architecture stretches from c. 900 B.C.E. to

the first century C.E. (with the earliest

extant stone architecture dating to the

seventh century B.C.E.). Greek architecture

influenced Roman architecture and architects

in profound ways, such that Roman Imperial

architecture adopts and incorporates many

Greek elements into its own practice. An

overview of basic building typologies

demonstrates the range and diversity of Greek

architecture.

"Hera II," c. 460

B.C.E., 24.26 x 59.98 m, Greek, Doric

temple from the classical period likely

dedicated to Hera, Paestum (Latin)

previously Poseidonia, photo: Steven

Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

"Hera II," c. 460

B.C.E., 24.26 x 59.98 m, Greek, Doric

temple from the classical period likely

dedicated to Hera, Paestum (Latin)

previously Poseidonia, photo: Steven

Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Temple

The most recognizably “Greek” structure is the temple (even though the architecture of Greek temples is actually quite diverse). The Greeks referred to temples with the term ὁ ναός (ho naós) meaning "dwelling;" temple derives from the Latin term, templum. The earliest shrines were built to honor divinities and were made from materials such as a wood and mud brick—materials that typically don't survive very long. The basic form of the naos emerges as early as the tenth century B.C.E. as a simple, rectangular room with projecting walls (antae) that created a shallow porch. This basic form remained unchanged in its concept for centuries. In the eighth century B.C.E. Greek architecture begins to make the move from ephemeral materials (wood, mud brick, thatch) to permanent materials (namely, stone).

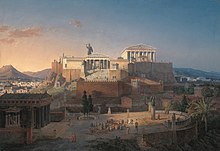

During the Archaic period the tenets of the Doric order of architecture in the Greek mainland became firmly established, leading to a wave of monumental temple building during the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E. Greek city-states invested substantial resources in temple building—as they competed with each other not just in strategic and economic terms, but also in their architecture. For example, Athens devoted enormous resources to the construction of the acropolis in the 5th century B.C.E.—in part so that Athenians could be confident that the temples built to honor their gods surpassed anything that their rival states could offer.

Greek architectural orders

The multi-phase architectural development of sanctuaries such as that of Hera on the island of Samos demonstrate not only the change that occurred in construction techniques over time but also how the Greeks re-used sacred spaces—with the later phases built directly atop the preceding ones. Perhaps the fullest, and most famous, expression of Classical Greek temple architecture is the Periclean Parthenon of Athens—a Doric order structure, the Parthenon represents the maturity of the Greek classical form.

Iktinos and Kallikrates, The Parthenon,

Athens, 447 – 432 B.C.E. ,

photo: Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA

2.0)

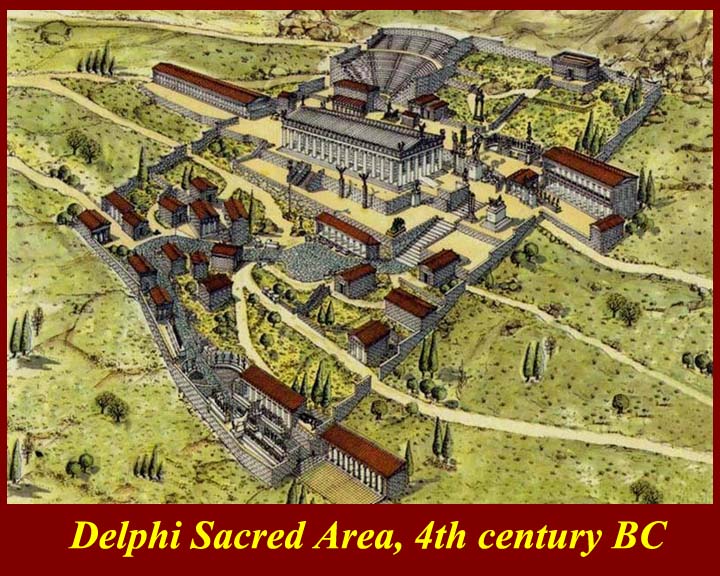

Tholos temple, sanctuary of Athena

Pronaia, 4th century B.C.E., Delphi,

Greece, photo: kufoleto (CC

BY 3.0)

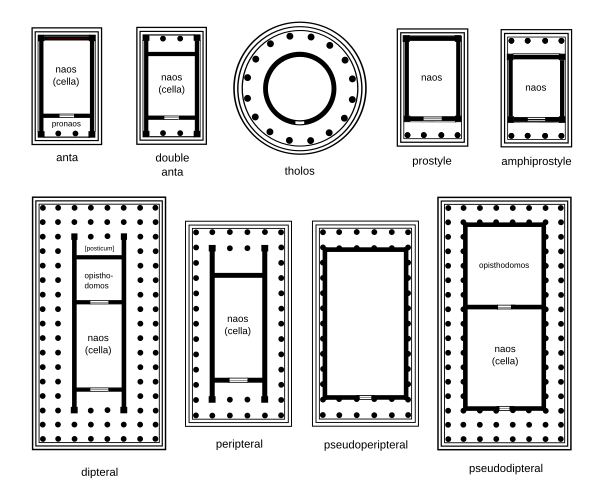

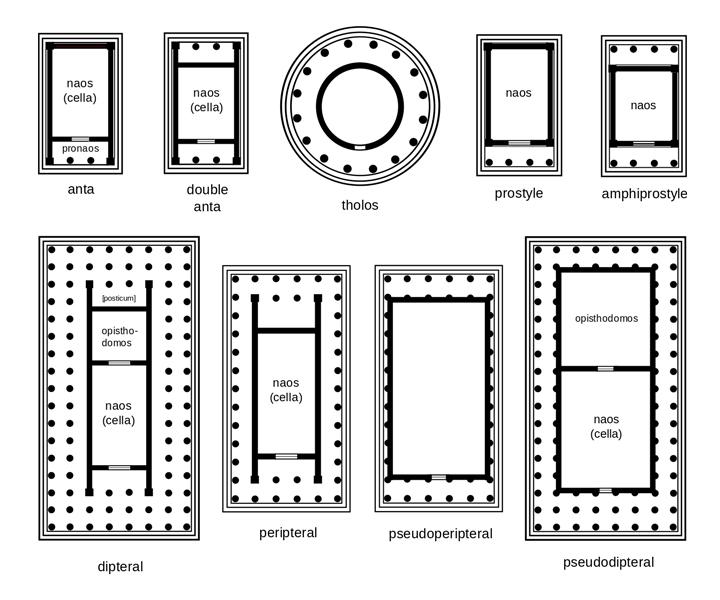

Greek temples are often

categorized in terms of their ground plan and

the way in which the columns are arranged. A

prostyle temple is a temple that has columns

only at the front, while an amphiprostyle

temple has columns at the front and the rear.

Temples with a peripteral arrangement (from

the Greek πτερον (pteron) meaning

"wing) have a single line of columns arranged

all around the exterior of the temple

building. Dipteral temples simply have a

double row of columns surrounding the

building. One of the more unusual plans is the

tholos, a temple with a circular ground plan;

famous examples are attested at the sanctuary

of Apollo in Delphi and the sanctuary of

Asclepius at Epidauros.

Greek temple plans (photo

source)

Stoa

Stoa (στοά) is a Greek architectural term that describes a covered walkway or colonnade that was usually designed for public use. Early examples, often employing the Doric order, were usually composed of a single level, although later examples (Hellenistic and Roman) came to be two-story freestanding structures. These later examples allowed interior space for shops or other rooms and often incorporated the Ionic order for interior colonnades.

P. De Jong, Restored Perspective of

the South Stoa, Corinth, photo: American

School of Classical Studies, Digital

Collections

Greek city planners came to prefer the stoa as a device for framing the agora (public market place) of a city or town. The South Stoa constructed as part of the sanctuary of Hera on the island of Samos (c. 700-550 B.C.E.) numbers among the earliest examples of the stoa in Greek architecture. Many cities, particularly Athens and Corinth, came to have elaborate and famous stoas. In Athens the famous Stoa Poikile (“Painted Stoa”), c. fifth century B.C.E., housed paintings of famous Greek military exploits including the battle of Marathon, while the Stoa Basileios (“Royal Stoa”), c. fifth century B.C.E., was the seat of a chief civic official (archon basileios).

20th century reconstruction of the Stoa of

Attalos in the Athenian Agora

(original c. 159-138

B.C.E.), photo: Steven

Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Later, through the patronage of the kings of Pergamon, the Athenian agora was augmented by the famed Stoa of Attalos (c. 159-138 B.C.E.) which was recently rebuilt according to the ancient specifications and now houses the archaeological museum for the Athenian Agora itself (see image above). At Corinth the stoa persisted as an architectural type well into the Roman period; the South Stoa there (above), c. 150 C.E., shows the continued utility of this building design for framing civic space. From the Hellenistic period onwards the stoa also lent its name to a philosophical school, as Zeno of Citium (c. 334-262 B.C.E.) originally taught his Stoic philosophy in the Stoa Poikile of Athens.

Theater

Theatre at the Sanctuary of Asclepius at

Epidaurus, c. 350 - 300 B.C.E.,

photo: Steven Zucker (CC

BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Greek theater was a large, open-air structure used for dramatic performance. Theaters often took advantage of hillsides and naturally sloping terrain and, in general, utilized the panoramic landscape as the backdrop to the stage itself. The Greek theater is composed of the seating area (theatron), a circular space for the chorus to perform (orchestra), and the stage (skene). Tiered seats in the theatron provided space for spectators. Two side aisles (parados, pl. paradoi) provided access to the orchestra. The Greek theater inspired the Roman version of the theater directly, although the Romans introduced some modifications to the concept of theater architecture. In many cases the Romans converted pre-existing Greek theaters to conform to their own architectural ideals, as is evident in the Theater of Dionysos on the slopes of the Athenian Acropolis. Since theatrical performances were often linked to sacred festivals, it is not uncommon to find theaters associated directly with sanctuaries.

Bouleuterion

Bouleuterion, Priène (Turkey), c. 200

B.C.E., photo: Jacqueline

Poggi

(CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Bouleuterion (βουλευτήριον) was an important civic building in a Greek city, as it was the meeting place of the boule (citizen council) of the city. These select representatives assembled to handle public affairs and represent the citizenry of the polis (in ancient Athens the boule was comprised of 500 members). The bouleuterion generally was a covered, rectilinear building with stepped seating surrounding a central speaker’s well in which an altar was placed. The city of Priène has a particularly well-preserved example of this civic structure as does the city of Miletus.

House

Greek

houses of the Archaic and Classical periods

were relatively simple in design. Houses

usually were centered on a courtyard that

would have been the scene for various ritual

activities; the courtyard also provided

natural light for the often small houses. The

ground floor rooms would have included kitchen

and storage rooms, perhaps an animal pen and a

latrine; the chief room was the andron—site

of the male-dominated drinking party (symposion).

The quarters for women and children (gynaikeion)

could be located on the second level (if

present) and were, in any case, segregated

from the mens’ area. It was not uncommon

for houses to be attached to workshops or

shops. The houses excavated in the southwest

part of the Athenian Agora had walls of mud

brick that rested on stone socles and tiled

roofs, with floors of beaten clay.

Plan, Olynthus

(Greece), House A vii 4, built after

432, before 348 B.C.E., from Olynthus,

vol. 8 pl. 99, 100 and fig. 5, kitchen

complex c, d, and e; andron

(k) (photo: Perseus Digital Library)

Plan, Olynthus

(Greece), House A vii 4, built after

432, before 348 B.C.E., from Olynthus,

vol. 8 pl. 99, 100 and fig. 5, kitchen

complex c, d, and e; andron

(k) (photo: Perseus Digital Library)

The city of Olynthus in Chalcidice, Greece, destroyed by military action in 348 B.C.E., preserves many well-appointed courtyard houses arranged within the Hippodamian grid-plan of the city. House A vii 4 had a large cobbled courtyard that was used for domestic industry. While some rooms were fairly plain, with earthen floors, the andron was the most well-appointed room of the house.

Fortifications

Fortifications and gate, Palairos (Greece)

The Mycenaean fortifications of Bronze Age Greece (c. 1300 B.C.E.) are particularly well known—the megalithic architecture (also referred to as Cyclopean because of the use of enormous stones) represents a trend in Bronze Age architecture. While these massive Bronze Age walls are difficult to best, first millennium B.C.E. Greece also shows evidence for stone built fortification walls. In Attika (the territory of Athens), a series of Classical and Hellenistic walls built in ashlar masonry (squared masonry blocks) have been studied as a potential system of border defenses. At Palairos in Epirus (Greece) the massive fortifications enclose a high citadel that occupies imposing terrain.

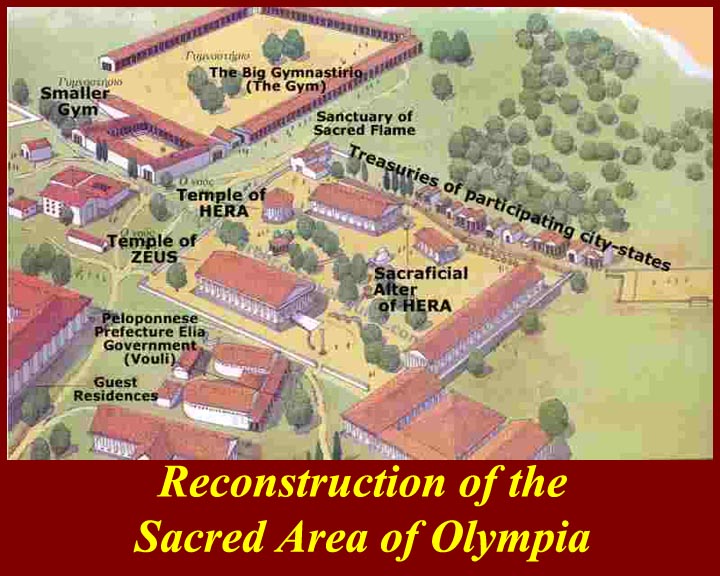

Stadium, Gymnasium, and Palaestra

The Greek stadium (derived from stadion, a Greek measurement equivalent to c. 578 feet or 176 meters) was the location of foot races held as part of sacred games; these structures are often found in the context of sanctuaries, as in the case of the Panhellenic sanctuaries at Olympia and Epidauros. Long and narrow, with a horseshoe shape, the stadium occupied reasonably flat terrain.

The gymnasium (from the Greek term gymnós meaning "naked") was a training center for athletes who participated in public games. This facility tended to include areas for both training and storage. The palaestra (παλαίστρα) was an exercise facility originally connected with the training of wrestlers. These complexes were generally rectilinear in plan, with a colonnade framing a central, open space.

Altar

Altar of Hieron II, 3rd century

B.C.E. (Syracuse, Sicily, Italy)

Since blood sacrifice was a key component of Greek ritual practice, an altar was essential for these purposes. While altars did not necessarily need to be architecturalized, they could be and, in some cases, they assumed a monumental scale. The third century B.C.E. Altar of Hieron II at Syracuse, Sicily, provides one such example. At c. 196 meters in length and c. 11 m in height the massive altar was reported to be capable of hosting the simultaneous sacrifice of 450 bulls (Diodorus Siculus History 11.72.2).

Model of the Pergamon Altar (Altar of

Zeus), c. 200-150 B.C.E. (Pergamon Museum,

Berlin) photo: Steven

Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Another spectacular altar is the Altar of Zeus from Pergamon, built during the first half of the second century B.C.E. The altar itself is screened by a monumental enclosure decorated with sculpture; the monument measures c. 35.64 by 33.4 meters. The altar is best known for its program of relief sculpture that depict a gigantomachy (battle between the Olympian gods and the giants) that is presented as an allegory for the military conquests of the kings of Pergamon. Despite its monumental scale and lavish decoration, the Pergamon altar preserves the basic and necessary features of the Greek altar: it is frontal and approached by stairs and is open to the air—to allow not only for the blood sacrifice itself but also for the burning of the thigh bones and fat as an offering to the gods.

Fountain house

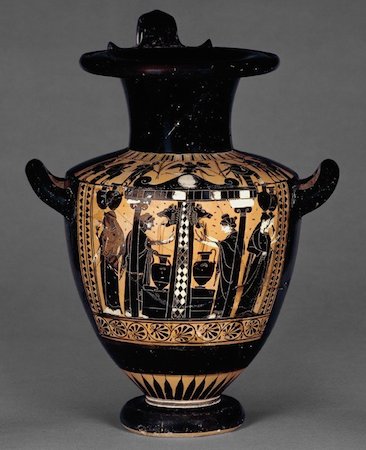

Black-figured water-jar (hydria) with a

scene at a fountain-house, Greek,

about 520-500 B.C.E., 50.8 cm high, © The

Trustees of the British Museum

The fountain house is a public building that provides access to clean drinking water and at which water jars and containers could be filled. The Southeast Fountain house in the Athenian Agora (c. 530 B.C.E.) provides an example of this tendency to position fountain houses and their dependable supply of clean drinking water close to civic spaces like the agora. Gathering water was seen as a woman’s task and, as such, it offered the often isolated women a chance to socialize with others while collecting water. Fountain house scenes are common on ceramic water jars (hydriai), as is the case for a Black-figured hydria (c. 525-500 B.C.E.) found in an Etruscan tomb in Vulci that is now in the British Museum

Legacy

The architecture of ancient Greece influenced ancient Roman architecture, and became the architectural vernacular employed in the expansive Hellenistic world created in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great. Greek architectural forms became implanted so deeply in the Roman architectural mindset that they endured throughout antiquity, only to then be re-discovered in the Renaissance and especially from the mid-eighteenth century onwards as a feature of the Neo-Classical movement. This durable legacy helps to explain why the ancient Greek architectural orders and the tenets of Greek design are still so prevalent—and visible—in our post-modern world.

Essay by Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker

Additional resources:

Architecture in Ancient Greece on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

B. A. Ault and L. Nevett, Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

N. Cahill, Household and City Organization at Olynthus (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001).

J. J. Coulton, The Architectural Development of the Greek Stoa (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976).

J. J. Coulton, Ancient Greek Architects at Work: Problems of Structure and Design (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1982).

W. B. Dinsmoor, The Architecture of Greece: an Account of its Historic Development 3rd ed. (London: Batsford, 1950).

Marie-Christine Hellmann, L’architecture Grecque 3 vol. (Paris: Picard, 2002-2010).

M. Korres, Stones of the Parthenon (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000).

A. W. Lawrence, Greek Architecture 5th ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

C. G. Malacrino, Constructing the Ancient World: Architectural Techniques of the Greeks and Romans (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010).

A. Mazarakis Ainian, From Rulers' Dwellings to Temples: Architecture, Religion and Society in early Iron Age Greece (1100-700 B.C.) (Jonsered: P. Åströms förlag, 1997).

L. Nevett, House and Society in the Ancient Greek World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

J. Ober, Fortress Attica: Defense of the Athenian Land Frontier, 404-322 B.C. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1985).

D. S. Robertson, Greek and Roman Architecture 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969).

J. N. Travlos, Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens (New York: Praeger, 1971).

F. E. Winter, Greek Fortifications (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971).

F. E. Winter, Studies in Hellenistic Architecture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006).

W. Wrede, Attische Mauern (Athens: Deutsches archäologisches Institut, 1933).

R. E.

Wycherley, The Stones of Athens

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978).

3 Greek

Architecture (c.900-27 BCE)

From

http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/architecture/greek.htm

[some Internet links added -- tkw]

Temple of

Hephaistos (449 BCE)

Athens. A masterpiece of ancient art and

one of the best-preserved

temples of Classical

Antiquity.

Contents

• Introduction

• Greek

Architecture: Why is it Important?

• Origins

• Development

of Stone Architecture

• Types

of Buildings

• The

Greek Temple

- Layout

- Base

and Walls

- Roof

- Column

and Lintel

- Entablature

and Pediment

- How

Stone Temples Were Built

• Orders

of Greek Architecture (see: IMAGE)

- History

• Doric

Order

- The

Parthenon

- Architectural

Sculptures of the Parthenon

• Ionic

Order

- The

Erechtheion

• Corinthian

Order

• Legacy

of Greek Architecture

• Famous

Greek Temples

• Ancient

Greek Architects

The architecture of Ancient Greece concerns the buildings erected on the Greek mainland, the Aegean Islands, and throughout the Greek colonies in Asia Minor (Turkey), Sicily and Italy, during the approximate period 900-27 BCE. Arguably the greatest form of Greek art, it is most famous for its stone temples (c.600 onwards), exemplified by the Temple of Hera I at Paestum, Italy; the Parthenon , Erechtheum, and Temple of Athena Nike, all on the Acropolis at Athens; and the Temple of the Olympian Zeus at the foot of the Acropolis. As well as temples and altars, Greek designers - who included some of the greatest architects of classical antiquity - are also famous for the design of their theatres (c.350 onwards), public squares, stadiums, and monumental tombs - exemplified by the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos (c.353 BCE), Turkey. Like Greek sculpture, Greece's architecture is traditionally divided into three periods: Archaic (c.650-480 BCE); Classical (c.480-323 BCE) and Hellenistic (c.323-27 BCE).

Greek Architecture: Why is it Important?

Greek architecture is important

for several reasons: (1) Because of its

logic and order. Logic and order are at the

heart of Greek architecture. The Hellenes

planned their temples according to a coded

scheme of parts, based first on function,

then on a reasoned system of sculptural

decoration. Mathematics determined the

symmetry, the harmony, the eye's pleasure.

There had never been an architecture in just

this sense. Egyptian

pyramid architecture had been an

early, attempt, but Greek building art

offered the first clear, strong expression

of a rational, national architectural creed.

It is the supreme example of the intellect

working logically to create a unified

aesthetic effect. Greek designers used

precise mathematical calculations to

determine the height, width and other

characteristics of architectural elements.

These proportions might be changed slightly,

and certain individual elements (columns,

capitals, base platform), might be tapered

or curved, in order to create the optimum

visual effect, as if the building was a

piece of sculpture. (2) Because of its

invention of the classical "orders": namely,

namely, the Doric Order, the Ionic Order and

the Corinthian Order - according to the type

of column, capital and entablature used. (3)

Because of its exquisite architectural

sculpture. Architects commissioned sculptors

to carve friezes, statues and other

architectural sculptures, whose beauty has

rarely, if ever, been equalled in the history

of art. (4) Because of its influence

on other schools. Although Greek architects

rarely progressed further than simple

post-and-lintel building techniques, and

failed to match the engineering techniques

(arch, vault) developed in Roman

architecture, they succeeded in

creating the most beautiful, monumental

structures of the Ancient World. Their

formulas - devised as far back as 550 BCE -

paved the way for Renaissance and

Neoclassical architecture, and had the

greatest possible influence on the

proportions, style and aesthetics

of the 18th and 19th centuries. Modern

architects, too, have been influenced by

Greek architectural forms. Louis Sullivan

(1856-1924), for instance, a leading figure

in the First Chicago School, based a number

of his skyscraper designs on the Greek

template of base, shaft, and capital, while

using vertical bands (reminiscent of the

fluting on Greek columns) to draw the eye

upwards.

The origins of Greek architectural design are not to be found in the various strands of Aegean art that appeared in the eastern Mediterranean, notably Minoan or Mycenean art, but in the Oriental cultures that poured their influences into the Greek settlements along the shore of Asia Minor (Turkey) and from there to Hellas itself. Ever since the Geometric Period (900-725 BCE), the main task of the Greek architect was to design temples honouring one or more Greek deities. In fact, until the 5th century BCE it was practically his only concern. The temple was merely a house (oikos) for the god, who was represented there by his cult statue, and most Geometric-era foundations indicate that they were constructed according to a simple rectangle. According to ceramic models (like the 8th century model found in the Sanctuary of Hera near Argos), they were made out of rubble and mud brick with timber beams and a thatched or flat clay roof. By 700 BCE, the latter was superceded by a sloping roof made from fired clay roof tiles. Their interiors used a standard plan adapted from the Mycenean palace megaron. The temple's main room, which contained the statue of the god, or gods, to whom the building was dedicated, was known as the cella or naos. (For more about the history of Greek architecture, see: Ancient Greek Art: c.650-27 BCE.)

Development of Stone Architecture

Until roughly 650 BCE, mid-way through the Orientalizing Period (725-600 BCE), no temples were constructed in finished stone. However, from 650 BCE onwards, or thereabouts, there was a renewal of contacts and trade links between Greece and the Middle East, including Egypt, the home of stone architecture. (See: Ancient Egyptian Architecture.) As a result, Greek designers and masons became familiar with Egypt's stone buildings and construction techniques, including those of Imhotep, which paved the way for monumental architecture and sculpture in Greece. This process - known as "petrification" - involved the replacement of wooden structures with stone ones. Limestone was typically used for pillars and walls, while terracotta was used for roof tiles and marble for ornamentation. It was a gradual process, which began in the latter part of the 7th century, and some structures, like the temple at Thermum, consisted of timber and fired clay, as well as stone.

Building Design in Ancient Egypt

Early Egyptian Architecture (c.3100-2181 BCE).

Egyptian Middle Kingdom Architecture (2055-1650 BCE).

Egyptian New Kingdom Architecture (1550-1069 BCE).

Late Egyptian Architecture (1069 BCE - 200 CE).

At the same time, the switch from brick and timber to more permanent stone stimulated Greek architects to design a basic architectural "template" for temples and other similar public buildings. This first "template", known as the "Doric Order" of architecture, laid down a series of rules concerning the characteristics and dimensions of columns, upper facades and decorative works. Subsequent "templates" included the Ionic Order (from 600) and the Corinthian Order (from 450).

Unlike their Minoan and Mycenean ancestors, the Ancient Greeks did not have royalty, and therefore had no need for palaces. This was why their architecture was devoted to public buildings, such as the temple, including the small circular variant (tholos); the central market place (agora), with its covered colonnade (stoa); the monumental gateway or processional entrance (propylon); the council building (bouleuterion) the open-air theatre; the gymnasium (palaestra); the hippodrome (horse racing); the stadium (athletics); and the monumental tomb (mausoleum). But of all these buildings, it is the temple that best captures the qualities of Greek design.

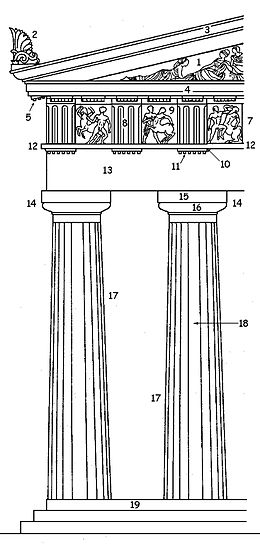

Figure 1. Greek Orders of Architecture

Except for the circular tholos, most Greek temples were oblong, roughly twice as long as they were wide. Most were small (30–100 feet long), although a few were more than 300 feet long and 150 feet wide. (For comparison, the dimensions of the Parthenon are 235 feet in length, 109 feet in width.) The typical oblong floor plan incorporated a colonnade of columns (peristyle) on all four sides; a front porch (pronaos), a back porch (opisthodomos). The upper works of the temple usually consisted of mudbrick and wood, except for the upper facade which was usually stone, and designed according to the Order (Doric, Ionic). Columns were typically carved from limestone, with upper facades usually decorated with marble.

The interior of the Greek temple typically consisted of an inner shrine (cella, or naos) which housed the cult statue, and sometimes one or two antechambers, which were used as storage places for devotees to leave their votive offerings, like money, precious objects, and weapons.

Note: For a brief comparison between the pagan Greek temple and the Christian church, see: Early Christian Art (150-1100).

The layout of the inner shrine, the other chambers (if any) and surrounding columns usually followed one of five basic designs, named as follows. (1) If the entrance to the cella incorporated a pair of columns, the building was known as a "templum in antis". ["in antis" means "between the wall pillars"] (Example: Siphnian Treasury, Delphi, 525 BCE; or Temple of Hera, Olympia, 590 BCE.) (2) If the entrance was preceded by a portico of columns across its front, the building was known as a prostyle temple. (Example: Temple B, Selinunte, Sicily, c.600-550 BCE.) (3) If in addition to the portico of columns at the front, there was a colonnade of columns at the rear exterior of the cella, the building was known as a amphiprostyle temple. (Example: Temple of Athena Nike, Athens, 425 BCE. Or see the later Temple of Venus and Roma, Rome, 141 CE.) (4) If the colonnade surrounded the entire building, it was known as a peripteral temple. (Example: The Parthenon, Athens, 447-437 BCE) (5) If the colonnade encircling the building comprised a double row of columns, it was known as a dipteral temple. (Example: The Heraion of Samos, 550 BCE; or Temple of Apollo, Didyma, Asia Minor, 313 BCE.)

The temple was built on a masonry base (crepidoma), which elevated it above the surrounding ground. The base usually consists of three steps: the topmost step is the "stylobate"; the two lower steps are the "stereobate". Like the Parthenon, most temples have a three-step base, although the Temple of Zeus at Olympus, has two, while the Temple of Apollo at Didyma has six. During the petrification process (650/600 BCE onwards), temples were given masonry walls, consisting mostly of local stone rubble, sometimes augmented by high quality ashlar masonry. Inside the temple, the inner sanctum (cella/naos) was made of stone, as were the antechambers, if any.

All early temples had a flat thatched roof, supported by columns (hypostyle), but as soon as walls were made from stone and could therefore support a heavier load, temples were given a slightly sloping roof, covered with ceramic terracotta tiles. These roof tiles could be up to three-feet long and weigh as much as 80 pounds.

Greek architects and building engineers knew about both the "arch" (see, for instance, The Rhodes Footbridge, 4th century BCE) and the "vault" (corbel and barrel types), but they made little use of either in their architectural construction. Instead, they preferred to rely on the use of "post and lintel" techniques, involving vertical uprights (columns or posts) supporting horizontal beams (lintels). This method, known as trabeated construction, dates back to earliest times when temples were made from timber and clay, and was later applied to stone posts and horizontal stone beams. However, it remained a relatively primitive method of roofing an area, since it required a large number of supporting columns.

The stone columns themselves usually consisted of a series of solid stone "drums" - set one upon the other, without mortar - but sometimes joined inside with bronze pegs. The diameter of columns usually decreases from the bottom upwards, and to correct any illusion of concavity, Greek architects usually tapered them with a slight outward curve: an architectural technique known as "entasis".

Each column is composed of a shaft and a capital; some also have a base. The shaft may be decorated with vertical or spiral grooves, called fluting. The capital has two parts: a rounded lower part (echinus), above which is a square-shaped tablet (abacus). The appearance of the echinus and abacus varies according to the stylistic "template" or "Order" used in the temple's construction. Doric Order capitals are plainer and more austere, while Ionic and Corinthian capitals are more ornate.

The temple's columns support a two-tier horizontal structure: the "entablature" and the "pediment". The entablature - the first tier - is the major horizontal structural element supporting the roof, and encircles the whole building. It is made up of three sections. The lowest section is the "architrave", made up of a series of stone lintels which span the spaces between the columns. Each joint sits directly above the centre of each capital. The middle section is the "frieze", consisting of a broad horizontal band of relief sculpture. In Ionic and Corinthian temples, the frieze is continuous; in Doric temples sections of frieze (metopes) alternate with grooved rectangular blocks (triglyphs). The top part of the entablature immediately under the roof is the "cornice", which overhangs and protects the frieze.

The second tier is the pediment, a shallow triangular structure occupying the front and rear gable of the building. Traditionally, this triangular space contained the most important sculptural reliefs on the exterior of the building.

The design and construction of Greek temples was dependent above all on local raw materials. Fortunately, although Ancient Greece possessed few forests, it had lots of limestone, which was easily worked. In addition, there were plentiful supplies (on the mainland and the islands of Paros and Naxos) of high grade white marble for architectural and sculptural decoration. Lastly, deposits of clay, used for both roof tiles and architectural decoration, were readily available throughout the country, notably around Athens.

However, the quarrying and transport of stone was both costly and labour-intensive, and typically accounted for most of the cost of building a temple. It was only the wealth which Athens had accumulated after the Persian Wars, that enabled Pericles (495-429) to build the Parthenon (447-422 BCE) and other stone monuments on the Acropolis, at Athens. In some cases, older stone monuments were cannibalized for their marble and other precious stones.

Typically, each building project was controlled and supervised by the architect, who oversaw every aspect of construction. He selected the stone, managed its extraction, and supervised the craftsmen who cut and shaped it at the quarry. At the building site, master stone masons made the final precise carvings, to ensure that each stone block would slot into place without the need for mortar. After this, labourers hoisted each block into position. The architect also supervised the professional sculptors, who carved the reliefs on the frieze, metopes and pediments, as well as the painters who painted the sculptures and various architectural elements of the building.

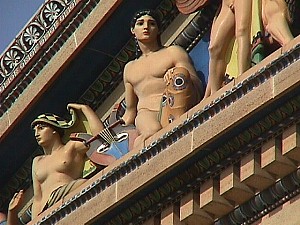

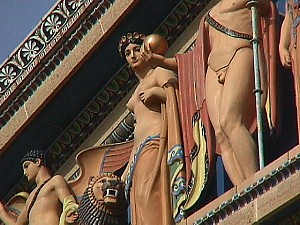

Don't forget, the Greeks regularly painted their marble temples. In fact they seem not only to have painted them, but to have used gaudy colours for the purpose, indulging generously in red, blue, and gold. There must have been some attempt to correlate colour and structure, with the structural members kept clear and outstanding, the lower parts little coloured, and the upper parts alone flowering in hue as they did in sculptural adornment, but all evidence has long since vanished. See also: Greek Painting: Classical Period, and Greek Painting: Hellenistic Period.

Ancient Greek architecture devised three main "orders" or "templates": the Doric Order, the Ionic Order and the Corinthian Order. These Orders laid down a broad set of rules concerning the design and construction of temples and similar buildings. These rules regulated the shape, details, proportions, and proportional relationships of the columns, capitals, entablature, pediments and stylobate.

Take proportions, for instance, which are critical for the overall appearance of a building, especially a cult temple. The Doric Order stipulated that the height of a column should be five and a half times greater than its diameter, while the Ionic Order laid down a slimmer more elegant ratio of nine to one.

That said, Ancient Greek architects took a highly pragmatic approach to the rules surrounding proportions, and when it came to the mathematics of an architectural design they took "appearance" as their guiding principle. In other words, if the correct mathematical proportions didn't look right, they used a different set! In particular, they treated a temple like a sculptor treats a statue: they wanted it to look good from every angle. So they added a bit of width here, a bit of height there, and so on, until the structure looked perfect. As a result, measurements of Doric and Ionic temples can vary tremendously, so don't take the measurements and ratios, quoted below, too literally.

History of Greek Architectural Orders

Historically, the two early orders, the Doric and the Ionic, have parallels, if not antecedents, in earlier Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Persia. The stronger of the two, the Doric, retains primitive heaviness and the effect of powerful stability. It was a favourite with the Greek builders through the Archaic period (c.650-480 BCE); it was standard in the Greek settlements in Sicily and Italy, and was chosen for the Parthenon; but it gave way to the more ornamental types in the fourth century. The Doric column and capital are not unlike those to be observed in the Egyptian tombs at Beni-Hasan, though it is not necessary to infer direct copying from that model. (See also: Egyptian Art: 3100-395 BCE; Mesopotamian Art: 4500-539 BCE; and Ancient Persian Art: 3500-330 BCE.)

The more graceful and lighter Ionic order, however, has too many parallels in Eastern building not to be marked as an importation from the Orient. Probably the Egyptian lotus-capital had had echoes in Mesopotamia; and Ionian culture had developed in advance of that of the Greek mainland, partly due to the influence of Assyrian art (c.1500-612 BCE). When the Ionians refined the feature into something distinctively their own, they carried it back to the Athenians, who were their blood brothers.

At any rate, the austere Doric Order appeared on the Greek mainland during the pre-Archaic period and spread from there to Italy. It was well established in its mature form by 600 BCE, the approximate date of the Temple of Hera at Olympia. The more decorative Ionic order only arrived about 600 BCE, and co-existed thereafter alongside the Doric, being the favourite style of the rich and highly influential Greek cites of Ionia, along today's western coast of Turkey, as well as a number of other Aegean Islands. (Example: the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.) It reached its mature form during the High Classical period, around 450 BCE. The flamboyant Corinthian Order, which elaborated many of the characteristic features of the Ionic Order, did not emerge until the era of Hellenistic art and was fully developed by the Romans.

The Doric order is easily identified by its plain capital, and lack of column-base. Its echinus started out flat and more splayed in Archaic-era temples, before becoming deeper and more curvaceous in Classical-era temples, and smaller and straighter during the Hellenistc period. Doric columns nearly always have grooves, or flutes (usually 20), which run the full length of the column. The flutes have sharp edges known as arrises. At the top of the columns, there are three horizontal grooves known as the hypotrachelion.

The columns in early Doric-style temples (Temple of Apollo at Syracuse, Sicily, 565 BCE), may have a height to base-diameter ratio of only 4:1. Later, a ratio of 6:1 became more usual. During the Hellenistic era (323-27 BCE), the typically solid, masculine look of the Doric temple was partly replaced by slender, unfluted columns, with a height to diameter ratio of 7.5:1.

In the Doric order, there are clear rules about the positioning of architectural sculpture. Reliefs, for instance, are never used to decorate walls in an arbitrary way. They are always arranged in predetermined areas: the metopes and the pediment.

Doric temples are clearly identified by their sectioned, non-continuous frieze, with its alternating arrangement of scored triglyphs and sculpted metopes.

The Doric pediment, a notoriously difficult space in which to lay out a sculptural scene, was filled initially with relief sculpture. By the time of the Parthenon, sculptors had begun carving freestanding stone sculpture for the pediment. Even then, arranging figures inside the tapering triangular area continued to be problematical. But by the Early Classical period (480-450 BCE), as exemplified by the scenes carved at the temple of Zeus at Olympia, (460 BCE), sculptors had found the solution: they had a standing central figure flanked by rearing centaurs and fighting men shaped to fit each part of the space. At the Parthenon (c.435 BCE), the celebrated sculptor Phidias succeeded in filling the pediment with a complex arrangement of draped and undraped deities.

Doric Order temples occurs more often on the Greek mainland and at the sites of former colonies in Italy. Among the best-preserved examples of Archaic Doric architecture are the temple of Apollo at Corinth (540 BCE), and the temple of Aphaia, Aegina (490 BCE).

The supreme example of Doric architecture of the Classical Period (c.480-323 BCE) is of course the Parthenon (447-437 BCE) on the Athens Acropolis. It was a Greek sculptor, not an architect, who said that "successful attainment in art is the result of meticulous accuracy in a multitude of arithmetical proportions"; but the Parthenon is the aptest illustration. Every esoteric scholar delving into the mysteries of "the divine proportion" or "the golden mean" claims the Parthenon as his first example: it has so unfailingly pleased millions of eyes, and it measures out so exactly to a mathematical formula. In the whole aspect there are calculated proportionings of parts and rhythmic correspondences. Then on from the whole to the parts: the areas of the entablature are divided on logical and harmonious ratios; and of course there is the equally refined relationship of column and capital. Perfection within perfection! The Greek builders, in their search for "perfect" expressiveness, went on to optical refinements unparalleled elsewhere. The entasis, or slight swelling and recession of the profile of the column, is but one of the mathematical tricks to ensure in the beholder's eye the illusion of perfect straightness or exact regularity. Another is that the tops of the columns lean slightly toward the centre at each side of the colonnade, the inclination increasing in proportion as they are farther toward each end, because a row of columns which are actually parallel seems more widely spaced at the top corners. (The Parthenon columns of the outer colonnade are inclined, curiously enough, at such angles that all their axes would meet, if continued, at a point one mile up in the air.) Another concession to the eye is the slight curve upward at the centre of the main horizontal lines, made because straight steps or straight-set series of columns seem to sag slightly at the centre.

Architectural Sculptures of the Parthenon

In general the bases of the structure, the weight-bearing members, and the first horizontals, were kept clear of elaboration or figurative sculpture. In the Parthenon and earlier structures, it was deemed that the proper place for exterior sculptures was in the spaces between the triglyphs, or surviving beam-ends, and in the pediment. On the roof, single figures might be set in silhouette against the sky, at gable top and especially gable ends. Within the colonnade in some late Doric temples a continuous frieze ran like a band around the cella's exterior wall, and was seen in bits from the outside, between columns.

The marble sculpture on the Parthenon originally appeared on the building in two series, the continuous frieze within the colonnade and the separated panels between the triglyphs; and the two triangular compositions in the pediments. The best preserved of the figures were taken to England early in the nineteenth century, and are universally known, from the name of the man who carried them away in battered remnant form, as the "Elgin marbles."

There is grandeur in the pediment figures. They are among the world's leading examples of monumental sculpture. As in the case of the architectural monument of which they were decorative details, they doubtless have gained in sheer aesthetic value by the accidents of time. The grand votive statues, such as the outdoor Athena on the Acropolis and the colossal image of the same goddess in the cella of the Parthenon, were big enough, by all report, but they seem to have been distressingly and distractingly overdressed, and their largeness and sculptural nobility were lost in excessive detail. The magnitude of the pediment figures is the magnitude of the powerful in repose, of strength kept simple. In terms of narrative, the east pediment group represented the contest of Athena and Poseidon over the site of Athens. The west pediment composition illustrated the miraculous birth of Athena out of the head of Zeus.

The technical problem of fitting elaborate sculptural representations within the confined triangular space of a low pediment challenged the inventiveness and logic of sculptors collaborating on temple projects. At Aegina, Olympia, and Athens the solution balanced nicely with the architecture. There was a related flow of movement within the triangle, which was lost in later examples and certainly in every attempted modern imitation.

The panels between the triglyphs under the Parthenon cornice, known as the "metopes," originally ninety-two in number, have been even more disastrously defaced or destroyed than have the pediment groups during their twenty-three centuries of neglect. Each panel, almost square, bore two figures in combat. Sometimes the subjects were taken from mythology, while others are read today as symbolic of moral conflict.

The low-relief frieze which runs like a decorative band around the outside of the cella wall, within the colonnaded porch, is of another range of excellence. The subject is the ceremonial procession which was an event of the Panathenaic festival held every fourth year. The figures in the sculptural field, which is a little over four feet high and no less than 524 feet long, are mainly those of everyday Athenian life. Even the gods, shown receiving the procession, are intimately real and folk-like, though oversize. To them goes all the world of Athens: priests and elders and sacrifice-bearers, musicians and soldiers, noble youths and patrician maidens.

There is a casualness about the sculptured procession, an informality that would hardly have served within the severe triangles of the pediments. Everything is flowing and lightly accented. Particularly graceful and fluent are the portions depicting horsemen. The animals and riders move forward rhythmically, their bodies crisply raised from the flat and undetailed background. The sense of rhythmic movement, of plastic animation within shallow depth limits, is in parts of the procession superbly accomplished.

See also: History of Sculpture (from 35,000 BCE).

Unlike Doric designs, Ionic columns always have bases. Furthermore, Ionic columns have more (25-40) and narrower flutes, which are separated not by a sharp edge but by a flat band (fillet). They appear much lighter than Doric columns, because they have a higher column-height to column-diameter ratio (9:1) than their Doric cousins (5:1).

Ionic Order temples are recognizable by the highly decorative voluted capitals of their columns, which form spirals (volutes) similar to that of a ram's horn. In fact, Ionic capitals have two volutes above a band of palm-leaf ornaments.

In the entablature, the architrave of the Ionic Order is occasionally left undecorated, but more usually (unlike the Doric architrave) it is ornamented with an arrangement of overlapping bands. An Ionic temple can also be quickly identified by its uninterrupted frieze, which runs in a continuous band around the building. It is separated from the cornice (above) and architrave (below) by a series of peg-like projections, known as dentils.

In Ionic architecture, notably from 480 BCE onwards, there is greater variety in the types and quantity of mouldings and decorations, especially around entrances, where voluted brackets are sometimes employed to support an ornamental cornice over a doorway, such as that at the Erechtheum on the Athens acropolis.

Ionic columns and entablatures were always more highly decorated than Doric ones. In some Ionic temples, for instance, (quite apart from the ornamented echinus), certain Ionic columns (like those at the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus) contained a continuous frieze of figures around their lowest section, separated from the fluted section by a raised moulding.

The use of draped female figures (Caryatids) as vertical supports for the entablature, was a characteristic feature of the Ionic order, as exemplified by the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi (525 BCE) and the Erechtheion on the Athenian Acropolis.

The Erechtheion (421-406 BCE) is representative of the special features of the Ionic Order at its best. The almost fragilely graceful columns are there, the less severe massing, the breaking up of the entablature into more delicate units, and the general lightening of effect and greater enrichment by applied ornamentation. The East Porch (now restored) is, like the Parthenon, Greek architecture at its purest. The doorway within the North Portico has served a thousand architects as the classic model. The South Porch of the Erechtheion follows an innovation already seen at Delphi. Six statues of maidens, known as caryatids, took the place of the conventional columns. The experiment leaves the building somewhere between architecture and sculpture, and the result is interesting as a novelty rather than for any defensible daring or good purpose in the art of building. The statues very likely serve their purpose as supports today with more architectural plausibility than they could have done in the days when their arms, noses, and other members had not been shorn off. Even so, they are a bit ludicrously natural and unmathematical. As the Greeks failed here, so they often enough failed elsewhere. The monuments they left are not always the matchless and perfect compositions we have been led to believe by other generations.

Another famous Ionic building, this time from the Hellenistic Period (323-27 BCE) is the Altar of Zeus at Pergamon (c.166-156 BCE). As the name indicates, it was not a temple but merely an altar, possibly connected to the nearby Doric Temple of Athena (c.310 BCE). The Altar was accessed via a huge stairway leading to a flat Ionic-style colonnaded platform, and is noted for its 370-foot-long marble frieze depicting the Gigantomachy from Greek mythology. See also Pergamene School of Hellenistic Sculpture (241-133 BCE).

Corinthian Order of Architecture

The third order of Greek architecture, commonly known as the Corinthian Order, was first developed during the late Classical period (c.400-323 BCE), but did not become at all widespread until the Hellenistic era (323-27 BCE) and especially the Roman period, when Roman architects added a number of refinements and decorative details.

Unlike both the Doric and Ionic Orders, the Corinthian Order did not originate in wooden architecture. Instead, it emerged as an offshoot of the Ionic style about 450 BCE, distinguished by its more decorative capitals. The Corinthian capital was much taller than either the Doric or Ionic capital, being ornamented with a double row of acanthus leaves topped by voluted tendrils. Typically, it had a pair of volutes at each corner, thus providing the same view from all sides. According to the 1st century BCE Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius, the distinctive Corinthian capital was invented by a bronze founder, Callimarchus of Corinth. The ratio of the column-height to column-diameter in Corinthian temples is usually 10:1 (compare Doric 5.5:1; Ionic 9:1), with the capital accounting for roughly 10 percent of the height.

To begin with, the Corinthian Order of architecture was used only internally, as in the Temple of Apollo Epicurius, Bassae (450 BCE). In 334 BCE it was used on the exterior of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, and later on a huge scale at the Temple of the Olympian Zeus, Athens (174 BCE). During the late Hellenistic period, Corinthian columns were sometimes constructed without any fluting.

In addition to the Greek Orders

(Doric, Ionic and Corinthian) there were two

other styles of architecture. (1) The Tuscan

Order, a solid-looking Roman adaptation of

the Doric Order, famous for its unfluted

shaft and a plain echinus-abacus capital.

Not unlike the Doric in proportion and

profile, it is much plainer in style. The

ratio of its column-height to

column-diameter is 7:1. (2) The Composite

Order, only ranked as a separate order

during the era of

Renaissance art, is a late Roman

development of the Corinthian Order. It is

known as Composite because its capital

consists of both Ionic volutes and

Corinthian acanthus-leaf motifs. The ratio

of its column-height to column-diameter is

10:1.

The legacy of Greek architectural design lies in its aesthetic value: it created lots of beautiful buildings.

This beauty came not just from the grandeur and nobility of its architectural columns, but also from its ornamental features. The fluting of its columns, for instance, affords grace and vibration to the otherwise stolid shafts; but the channels reinforce rather than cut across support lines. The frieze is lifted above an architrave kept unadorned, preserving crossbar strength. The transitional members, capitals and moldings, agreeably soften the profile angles without loss of firmness. Supports are cushioned, but without undue softening. Just how great and distinctive are these achievements may be seen by contrast in Roman art when the insensitive Romans pick up the Greek elements and use them grandiosely and thoughtlessly, vulgarizing the ornamental features. Nevertheless, Greek ornament as a style of adornment in applied art was to be an overwhelming favourite in later ages, even down to the twentieth century. See also: Greatest Sculptors (from 500 BCE).

Whatever the precise ingredients of Greek building design, Western architects have tried for centuries to emulate the finished product. During the 15th and 16th centuries Renaissance architecture embraced the whole classical canon, albeit with a slightly more modern touch - examples include: Dome of Florence Cathedral, S Maria del Fiore, 1418-38, by Filippo Brunelleschi - for more on this, see: Florence Cathedral, Brunelleschi and the Renaissance (1420-36) - as well as Tempietto of S Pietro in Montorio, Rome, 1502 by Donato Bramante. Meantime, Venetian Renaissance architecture featured numerous villas in Vicenza and the Veneto designed by Andrea Palladio (1508-80), who himself influenced the English designer Inigo Jones (1573-1652).

Baroque architecture used Greek designs as the basis for many of its greatest creations (examples: St Peter's Basilica and St Peter's Square, 1504-1657, by Bernini et al; St Paul's Cathedral, London, 1675-1710, by Christopher Wren (1632-1723).

Eighteenth century architects in both Europe and North America rediscovered Greek designwork in Neoclassical architecture (examples: the Pantheon, Paris, begun 1737, by Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713-80); the iconic Brandenburg Gate in Berlin built by Carl Gotthard Langhans (1732-1808); the US Capitol Building, Washington DC, 1792-1827 by Thornton, Latrobe & Bulfinch; Baltimore Basilica, 1806-21, by Benjamin Latrobe; Walhalla, Regensburg, 1830-42, by Leo von Klenze). In nineteenth century architecture, Greek "Orders" were resurrected in both Europe and the United States through the Greek Revival movement. Even modern Art Nouveau architects like Victor Horta (1861-1947) borrowed from antique Greek designs.

For long periods of time Western Europe and America accepted the belief that artistic practice, even in the machine age, must be based upon study of these classic "Orders." This was part of the neo-Hellenism which was a religion in Europe, so that even in the 1920s Sir Banister Fletcher - the renowned architectural historian - could write: "Greek architecture stands alone in being accepted as above criticism, and therefore as the standard by which all periods of architecture may be tested." (A History of Architecture: 6th Edition, 1921.)

Ultimately, Greek architecture presents us with a concrete illustration of moral and spiritual truth. The solid foundation platform; the down-pressing mass of architrave, frieze, and roof-structure, counteracting the otherwise too powerful sense of lift, from the columns; the serenity of the colonnade, modified by the exuberance of sculptured frieze and pediment - all this may be seen as a tangible expression of the Greek combination of freedom and restraint, of perfectly poised aspiration and reason, of invention and discipline. The columns, some say, mark the rise toward truth or perfection; but the downbearing weight restores balance, caps the too aspiring lift. Thus Fate stops the too presumptuous human reach. This is the philosophical meaning of Greek architecture, which has entranced architects around the world for more than two thousand years.

DORIC

Temple

of Hera, Olympia (590 BCE)

Doric peripteral hexastyle building in the

Archaic style.

Temple

of Apollo, Syracuse, Sicily (565 BCE)

Doric peripteral hexastyle building.

Selinunte

Temple C, Sicily (550 BCE)

A peripteral hexastyle temple, it is one of

a series of Doric temples on the Selinunte

Acropolis. Metopes depicting the Labours of

Hercules are in the National Museum, at

Palermo.

The

Temple of Apollo, Corinth (540 BCE)

This Doric peripteral hexastyle temple

resembled the Temple of Hera at Olympia, but

was built entirely of stone.

Temple

of Hera I, Paestum (530 BCE)

Known as "the Basilica", it is one of the

earliest of all Doric temples to have

survived largely intact.

Selinunte

Temple G (The Great Temple of Apollo),

Sicily (520-450 BCE)

A Doric peripteral octastyle structure, it

is the largest temple at Selinunte and was

never finished.

Temple

of Apollo, Delphi (510 BCE)

This hexastyle Doric temple, supposedly

designed by legendary architects Trophonius

and Agamedes, was in fact erected by

Spintharus, Xenodoros and Agathon. Little

remains apart from foundations.

Temple

of Athena, Paestum (510 BCE)

Known as the Temple of Demeter, this Doric

peripteral hexastyle building displayed a

number of Ionic features, including the

columns of its pronaos.

Temple

of the Olympian Zeus, Agrigento, Sicily

510-409 BCE

Doric-style pseudoperipteral building.

Temple

of Aphaia, Aegina (490 BCE)

Doric peripteral hexastyle temple set high

on the east side of the island of Aegina.

Temple

of Athena, Syracuse, Sicily (480 BCE)

Doric hexastyle temple. Part of its

structure is now in Syracuse Cathedral.

Delian Temple

of Apollo, Delos (470 BCE)

Doric peripteral hexastyle building, now

largely in ruins.

Temple

of Hera Lacinia, Agrigento, Sicily

(460 BCE)

Doric temple constructed southeast of

Agrigento. It stands, along with the Temple

of Concord, the Temple of Zeus Olympias and

others, in the Valley of the Temples.

Temple

of Zeus, Olympia (460 BCE)

Doric peripteral hexastyle temple, designed

by Libon of Elis. Famous for its marvellous

pedimental sculpture, as well as its

colossal chryselephantine

sculpture of Zeus, sculpted by Phidias

(488-431 BCE), who also created the Statue

of Athena at the Parthenon.

Temple

of Poseidon, Paestum (460 BCE)

One of the best preserved Doric hexastyle

temples.

Temple

of Apollo Epicurius, Bassae (450 BCE)

Designed by the famous Greek architect

Ictinus, it incorporates elements from all

three Orders (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian).

Temple

on the Ilissus, Athens (449 BCE)

A small Ionic amphiprostyle tetrastyle

temple beside the Ilissus River, designed by

the Greek architect Callicrates.

Temple

of Hephaestos, Athens (449 BCE)

Also called the Theseion,

this exceptionally well-preserved Doric

peripteral hexastyle building now acts as an

Orthodox church.

The Parthenon,

Athens Acropolis (447-432 BCE)

The major Doric temple on the Acropolis of

Athens, and the quintessential work of Greek

High Classical architecture, it remains one

of the world's most influential and iconic

buildings. Built for Pericles by architects

Ictinus and Callicrates, and sculpted under

the direction of Phidias, who personally

created its huge chryselephantine cult

statue of Athena, it is based on a

peripetral octastyle ground plan. Although

its pedimental and metope relief sculpture

is laid out in the Doric style, it also has

an Ionic style frieze which encircles the

building.

Temple

of Poseidon, Sounion (444 BCE)

Doric peripteral hexastyle building.

Temple

of Nemesis, Rhamnous (436 BCE)

Doric hexastyle temple with an unfinished

stylobate.

Temple

of Concord, Agrigento, Sicily (430

BCE)

Well-preserved Doric peripteral hexastyle

temple.

Temple

at Segesta, Sicily (424 BCE)

Doric peripteral hexastyle building,

complete with unique unfluted columns.

Selinunte

Temple E (Temple of Hera), Sicily (5th

Century BCE)

The best preserved Doric peripteral

hexastyle temple at Selinunte, it belongs to

the eastern group along with Temples "F" and

"G".

Selinunte

Temple C, Sicily (5th Century BCE)

Doric hexastyle temple with a deep

colonnaded porch and a long narrow naos with

a second chamber.

IONIC

Temple

of Artemis, Ephesus, Asia Minor (560

BCE)

One of the Seven

Wonders of the Ancient World, the

bottom drum of the columns of this Dipteral

octastyle temple have an encircling

figurative frieze.

Temple

of Hera, Samos, Asia Minor (540 BCE)

Ionic dipteral temple designed by architects

Rhoikos and Theodoros of Samos.

Temple

of Athena Nike, Athens (427 BCE)

A small amphiprostyle tetrastyle building,

also known as "Nike Apteros" (Victory

without wings), this Ionic temple was

designed by Greek architect Callicrates.

Stands close to the Propylaea on the Athens

Acropolis.

The Erechtheion,

Athens Acropolis (421-406 BCE)

Ionic amphiprostyle hexastyle temple

dedicated to Athena Polias, designed by

Mnesicles.

Tholos

of Athena, Delphi (400 BCE)

A circular temple - with a Doric exterior

and a Corinthian interior - constructed by

Theodorus of Phocaea.

Temple

of Asclepius, Epidauros (380 BCE)

Doric hexastyle building designed by

Theodotus, featuring pedimental sculpture by

Timotheos.

Temple

of Artemis, Ephesus, Asia Minor (356

BCE)

Ionic Dipteral octastyle temple designed by

Greek architects Demetrius and Paeonius of

Ephesus, with reliefs by Skopas

(395-350 BCE), but no frieze.

Tholos

of Polycleitus, Epidauros (350 BCE)

Circular temple surrounded by 26 Doric

columns. Also has 14 internal

Corinthian-style columns.

The Philippeion,

Olympia (339 BCE)

Ionic tholos building, surrounded by 18

Ionic-style columns and 9 internal

Corinthian columns. Designed by architect

and sculptor Leochares

(4th Century BCE), it was erected to

commemorate Philip II of Macedon, father of

Alexander the Great.

Temple

of Athena Polias, Priene, Asia Minor

(334 BCE)

Ionic peripteral hexastyle temple designed

by Pythius of Priene. Like the Temple of

Artemis at Ephesus, it had no frieze.

Temple

of Artemis, Sardis, Asia Minor (325

BCE)

Ionic dipteral octastyle temple, one of the

biggest temples in Asia Minor, it was left

unfinished, and completed by the Romans.

Temple

of Dionysus, Teos, Asia Minor (193

BCE)

Ionic peripteral hexastyle temple designed

by architect Hermogenes of Priene.

CORINTHIAN

Temple

of Apollo Didymaeus, Miletus, Asia

Minor (310 BCE - 40 CE)

Ionic dipteral decastyle temple with

Corinthian features, designed by Greek

architects Paeonius of Ephesus and Daphnis

of Miletus.

Temple

of the Olympian Zeus, Athens (174 BCE)

One of the largest Corinthian dipteral

octastyle temples, it was designed by

architect Ossutius. Some of its columns were

taken to Rome before the temple was finished

and incorporated in the Temple of Jupiter

Capitolinus where they had a major impact on

Roman architecture.

For the top Greek sculptors of

the 5th century, see: Myron

(fl. 480-444 BCE), Polykleitos,

noted for his statue of Hera, and Callimachus

(fl. 432-408 BCE).

For the top sculptors of the 4th century BCE, see: Lysippos (c.395-305 BCE), official sculptor to Alexander the Great, and Praxiteles (Active 375-335 BCE), famous for his Aphrodite of Cnidus.

Few biographical details are known about the greatest Greek designers. While we know some of their names, and some of the buildings they designed, we know almost nothing about their training, or the extent of their careers. The most famous architects we know about, include:

Daphnis of Miletus,

Demetrius of Ephesus, an Artemision Temple slave (who, according to Pliny (Natural History 16213,-36.96), "completed " the Artemision, c. 440 BC with Paeonios of Ephesus. Possibly reconstruction after the temple burned in 356)

Hermogenes of Priene,

Hippodamus of Miletus,

Ictinus (mid-5th century BCE),

Libon of Elis,

Mnesicles (mid-5th century BCE),

Ossutius,

Paeonius of Ephesus,

Polykleitos the Younger,

Pythius of Priene,

Rhoikos of Samos,

Theodoros of Samos, and

Theodotus (Asclepios Temple, Epidaurus)

to name but a few.

Article in Quondam (19/1928) about the Philadelphia Museum of Art reviving Ancient Greek Architectural polychromy: http://www.quondam.com/19/1928.htm

Color was a vital factor in the art of ancient Greece. Vivid, primary colors were as important as form in its beauty. The Greeks interpreted architecture as the skillful combination of form and color. The invariably introduced color into their work. It was not a minor detail, infrequently used, as is generally assumed. Both their buildings and their sculpture were decorated with color. It is now conceded, after years of discussion, that there were evidences of color on the famous Elgin marbles of the Parthenon.

Although classical Greek architecture has flourished, the importance of color in relation to it has been ignored to such an extent that we have come to accept the monochrome treatment as the pure classical style. For this reason Philadelphia's attempt to revive Greek polychrome architecture and sculpture is looked upon as an audacious undertaking by the conservatives in art circles, and the architects, C. L. Borie, Jr., Horace Trumbauer and C.C. Zantzinger, designers of the new Museum of Art in Fairmount Park, are looked upon as pioneers. C. Paul Jennewein and John Gregory, sculptors, and Leon V. Solon, polychromist, are sharing the limelight focused on the builders of the museum.

In making the statement that the museum represents the first serious attempt to revive Greek polychrome treatment Mr. Solon, a recognized authority on polychromy, did not overlook the attempts that have been made to introduce color in buildings, particularly some of our modern skyscrapers. But he does not take these attempts seriously, inasmuch as the results show no evidence of comprehension of decorative capacities in the means that have been employed. "Color is a dangerous thing to use," he warns. It is a science to know which way colors will affect the proportion of ornament. Colors expand and contract the apparent size of areas.

Up to the present the Philadelphia Museum represents the first attempt to use terra cotta for serious sculptural purposes. Sculptured figures for the pediments as well as the architectural detail and roof tiles are of terra cotta. It is the first time that free standing sculpture has been baked in terra cotta to decorate a building, and it was necessary to build special kilns and revise the normal procedure to meet the conditions.

Besides the polychrome ornamentation there will be three main pediments with sculptured figures in polychrome. The pediments for the East and West pavilions have been completed by John Gregory and C. Paul Jennewein, sculptors, in collaboration with Mr. Solon. Mr. Jennewein is also responsible for the architectural modeling and the center and corner figure ornaments in gilt-bronze.

The building is not a copy of any Greek building, nor are the pediments or figure groups copies of Greek works. They are true to the Greek tradition in the use of color and detail but are entirely original in conception. As such, the museum unquestionably will be an important and beautiful contribution to the world's architectural creations.

Exhaustive research convinced Mr. Solon that the use of color was a highly organized art with the Greeks. They always applied color to certain parts of buildings. It was never used on any important feature that performed the function of supporting the building, such as an exterior wall or the shaft of a column, but was confined to the decorative features. Capitals of columns were decorated, but the shafts or bases never. Although the Greek principle was absolutely adhered to in the Philadelphia Museum certain deviations from Greek practice were necessitated by existing conditions. For instance, the range of observation in Greece is small, whereas the museum will be viewed from long range. Through much experimentation and closest possible cooperation between sculptors and polychomist highly satisfactory results have been evolved at Fairmount Park. In some cases sculptural detail had to be revised to facilitate distribution of color. Only brilliant colors were used on account of their visibility at long range. These colors had to be interrelated, one figure to another and carefully spaced throughout the whole group.

When questioned about the modeling of features Mr. Gregory stated that polychrome sculpture demands that faces be modeled like masks and depend upon color for expression and characteristics. The use of color in sculpture demands flat surfaces. Detail otherwise brought out by modeling is provided by color in polychrome sculpture. He found that the most important thing he had to keep in mind was to work in vertical planes in order to eliminate shadows, inasmuch as the color would be affected by dark shadows.

"The East" demanded, of course, more colorful treatment than "The West," represented by Mr. Jennewein's pediment group for the West Pavilion. The dark-skinned figures of "The East" demanded also the predominating use of a deep ivory tone in the draperies to carry out the harmony with the building material, a matter of vital importance. "Kato" stone was selected for the exterior because of its golden-orange tone clouded with silver-gray, which offers an ideal background for the brilliant colors used in the decorations. It is much warmer in tone than ordinary sandstone.

In giving an interpretation of his group, Mr. Jennewein explained that he based his theme on sacred and profane love, the two great underlying forces behind the development of Western art and civilization.

According to the sculptors one of the problems that demand careful working out was the arrangement of patterns that would permit natural divisions for the cutting of figures so that the joining would not mar the effect. The use of terra cotta imposed a three-foot length, and the central figures, which are to be eleven and one-half feet high, will be in four sections.

Roof tiles of terra cotta, measuring approximately three feet square, also carry out the polychrome effect. They are a grayish blue glaze on the face, with a dark blue edge, so that the coloring of the roof deepens with the foreshortening of the tiles as the building is approached. The beauty of the roof is enhanced by the varying colors of the sky, which are reflected in the surface of the tiles.

In discussing the treatment of polychrome Mr. Solon said that Greek processes would not serve in the American climate, so terra cotta was chosen because of its durability and the availability of all the colors needed.

Anne Lee, "Color Sculpture and Architecture: Philadelphia Revives the Ancient Art of Greek Polychrome" in The Mentor (May 1928) pp. 41-44.

5 Acropolis of Athens

Coordinates: 37.971421°N 23.726166°E

| Acropolis, Athens | |

|---|---|

|

The Acropolis of Athens (Ancient Greek: Ἀκρόπολις;[1] Modern Greek: Ακρόπολη Αθηνών Akrópoli Athinón) is an ancient citadel located on a high rocky outcrop above the city of Athens and contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historic significance, the most famous being the Parthenon. The word acropolis comes from the Greek words ἄκρον (akron, "highest point, extremity") and πόλις (polis, "city").[2] Although there are many other acropoleis in Greece, the significance of the Acropolis of Athens is such that it is commonly known as "The Acropolis" without qualification.

While there is evidence that the hill was inhabited as far back as the fourth millennium BC, it was Pericles (c. 495 – 429 BC) in the fifth century BC who coordinated the construction of the site's most important buildings including the Parthenon, the Propylaia, the Erechtheion and the Temple of Athena Nike.[3][4] The Parthenon and the other buildings were seriously damaged during the 1687 siege by the Venetians in the Morean War when the Parthenon was being used for gunpowder storage and was hit by a cannonball.[5]

The Acropolis was formally proclaimed as the pre-eminent monument on the European Cultural Heritage list of monuments on 26 March 2007.[6]

Contents

History

Early settlement

The Acropolis is located on a flat-topped rock that rises 150 m (490 ft) above sea level in the city of Athens, with a surface area of about 3 hectares (7.4 acres). It was also known as Cecropia, after the legendary serpent-man, Cecrops, the first Athenian king. While the earliest artifacts date to the Middle Neolithic era, there have been documented habitations in Attica from the Early Neolithic (6th millennium BC). There is little doubt that a Mycenaean megaron stood upon the hill during the late Bronze Age. Nothing of this megaron survives except, probably, a single limestone column-base and pieces of several sandstone steps.[7] Soon after the palace was constructed, a Cyclopean massive circuit wall was built, 760 meters long, up to 10 meters high, and ranging from 3.5 to 6 meters thick. This wall would serve as the main defense for the acropolis until the 5th century.[8] The wall consisted of two parapets built with large stone blocks and cemented with an earth mortar called emplekton (Greek: ἔμπλεκτον).[9] The wall follows typical Mycenaean convention in that it followed the natural contour of the terrain and its gate was arranged obliquely, with a parapet and tower overhanging the incomers' right-hand side, thus facilitating defense. There were two lesser approaches up the hill on its north side, consisting of steep, narrow flights of steps cut in the rock. Homer is assumed to refer to this fortification when he mentions the "strong-built House of Erechtheus" (Odyssey 7.81). At some point before the 13th century BC, an earthquake caused a fissure near the northeastern edge of the Acropolis. This fissure extended some 35 meters to a bed of soft marl in which a well was dug.[10] An elaborate set of stairs was built and the well served as an invaluable, protected source of drinking water during times of siege for some portion of the Mycenaean period.[11]

The Dark Ages

There is no conclusive evidence for the existence of a Mycenean palace on top of the Athenian Acropolis. However, if there was such a palace, it seems to have been supplanted by later building activity. Not much is known as to the architectural appearance of the Acropolis until the Archaic era. In the 7th and the 6th centuries BC, the site was taken over by Kylon during the failed Kylonian revolt,[12] and twice by Peisistratos: all attempts directed at seizing political power by coups d'état. Peisistratos built an entry gate or Propylaea and perhaps embarked on the construction of an earlier temple on the site of the Parthenon where fragments of sculptured limestone have been found as well as the foundations of a large unfinished temple.[13] Nevertheless, it seems that a nine-gate wall, the Enneapylon,[14] had been built around the biggest water spring, the "Clepsydra", at the northwestern foot.

Archaic Acropolis

A temple to Athena Polias (protectress of the city) was erected around 570–550 BC. This Doric limestone building, from which many relics survive, is referred to as the Hekatompedon (Greek for "hundred–footed"), Ur-Parthenon (German for "original Parthenon" or "primitive Parthenon"), H–Architecture or Bluebeard temple, after the pedimental three-bodied man-serpent sculpture, whose beards were painted dark blue. Whether this temple replaced an older one, or just a sacred precinct or altar, is not known. Probably, the Hekatompedon was built where the Parthenon now stands.[15]