[Click this line to jump directly to the BALTIC/NORTHERN CRUSADE]

[Click this line to jump to images of Cathar crusaders and defenders]

From http://atheism.about.com/library/FAQs/christian/blchron_xian_crusades08.htm

Cathar (Albigensian) & Baltic Crusades 1208 - 1300

Although Muslims obviously suffered at the hands of good Christians throughout the Middle Ages, it should not be forgotten that pagans and other Christians suffered just as much. Augustine's exhortation to compel entry into the church was used with great zeal when church leaders dealt with Christians who dared to follow a different sort of religious path. Pagans in the north were targeted for forced conversion.

| 1208 - 1229 | A Crusade against the Cathars (Albigenses) in southern France is launched by Pope lnnocent III. |

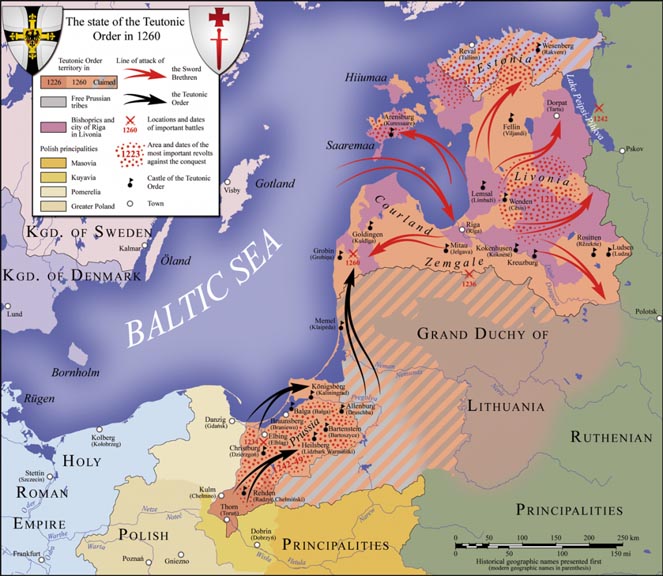

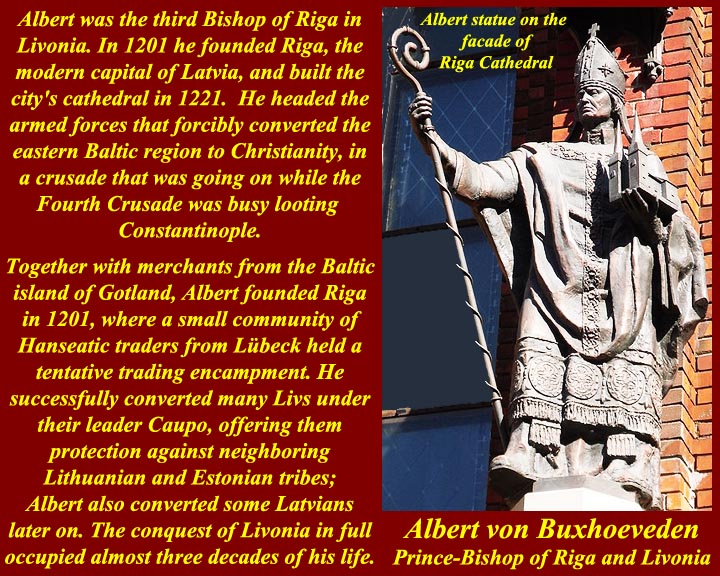

| 1208 | Albert, the third Bishop of Buxtehude (Uexküll), makes strong advances in the Baltic Crusade by forcibly converting the Kur and Lett peoples to Christianity. Albert and the Swordbrothers make great use of the fact that most of the tribes in the region are not on good terms with each other. The most effective means for advancing Christianity is to conquer one group, which would not be aided by anyone else, and then convince them to launch an attack on a neighbor whom they already disliked. In this manner one tribe after another was absorbed into Christendom. |

| January 1208 | Pierre de Castelnau, a papal legate in southern France who had been making some progress in converting Cathar heretics (also known as Albigensians) to orthodox Catholicism, is murdered. This sparks an outcry and, later this same year, a violent Crusade against the Cathars and the Waldenses in Southern France called by Pope Innocent III. |

| June 1209 | Raymond VI of Toulouse agrees to the demands of Pope Innocent III that he act against the Cathars after finding that more than 10,000 Crusaders had gathered at Lyon to lay waste to Cathar areas in southern France. |

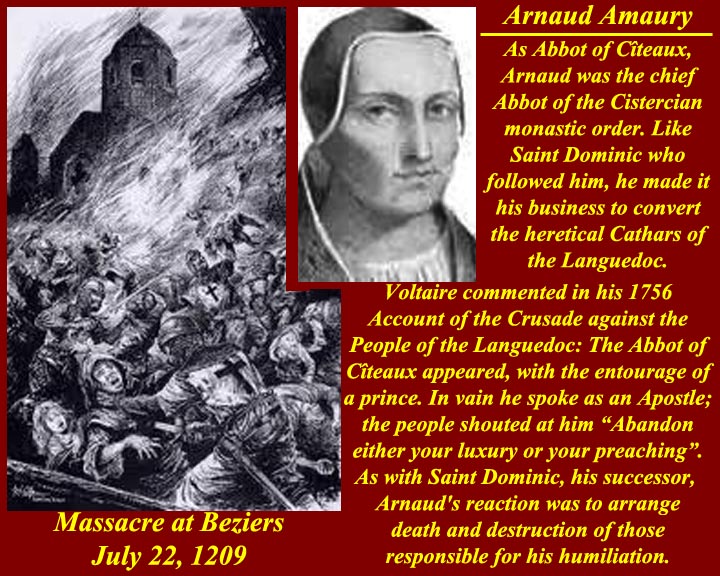

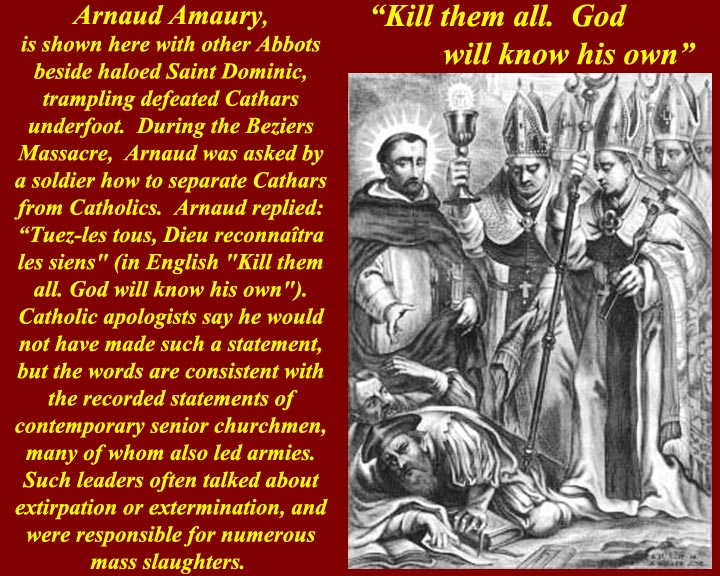

| July 22, 1209 | The city of Beziers in southern France is sacked and its population of around 10,000 massacred by the Abbot of Citeaux during the Crusade against the Cathars. Caesar of Heisterbach, the papal representative, records Abbot Arnaud-Amaury saying "Caedite eos! Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius" (Latin for "Slay them all! God will know his own.") |

| August 01, 1209 | Crusaders arrive at the French town of Carcassonne, controlled by Raymond-Roger de Trencavel and believed to be a Cathar stronghold. |

| August 07, 1209 | During the Crusader siege of Carcassonne the city's access to water is cut off. Raymond-Roger de Trencavel attempts to negotiate but is taken prisoner while under a flag of truce. |

| August 15, 1209 | The city of Carcassonne surrenders to the Crusaders. Unlike at Beziers the citizens are not killed but they are all forced to leave. Raymond-Roger de Trencavel is executed and Simon de Montfort, commander of the Crusader army, assumes control of the city and surrounding region for himself. |

| December 1209 | Crusaders attack the castle of Cabaret, near the French town of Lastours. Pierre-Roger de Cabarat manages to hold out, however. |

| March 1210 | Crusaders in southern France lay siege to Bram and, after capturing it, kill the Cathars living there. |

| July 22, 1210 | Citizens of the fortified town of Minerve in southern France surrender to the Crusaders seeking out Cathars. Those who were willing to convert were allowed to do so but the 140 who refused were burned at the stake. |

| August 1210 | Crusaders in southern France trying to root out the Cathar movement lay siege to the town of Termes. |

| December 1210 | The town of Termes falls to the Crusaders after a siege that had lasted since August. |

| 1211 | Crusading Bishop Albert lays the cornerstone for Riga's Dome Cathedral. By this point much of modern-day Latvia had been converted to Christianity and German merchants are settling throughout the region. |

| March 1211 | Crusaders return to the castle of Cabaret and this time Pierre-Roger de Cabarat surrenders. |

| May 1211 | Crusaders capture the castle of Aimery de Montréal, hanging several knights and burning several hundred Cathars who had fought there. |

| June 1211 | Crusaders attempt to besiege the city of Toulouse, but they are short of supplies and must withdraw. |

| September 1211 | Raymond of Toulouse leads an attack on Simon de Monfort at Castelnaudary. Monfort is able to escape, but Castelnaudary falls to the Cathars and Raymond goes on to liberate over thirty Cathar towns in the province of Toulouse before his counter-Crusade peters out at Lastours. |

| 1212 | The Children's Crusade is supposedly launched by the 12-year old French boy Stephen de Cloyes. More than 50,000 children are thought to have been sold into slavery, but many historians disbelieve that this Crusade ever occurred. |

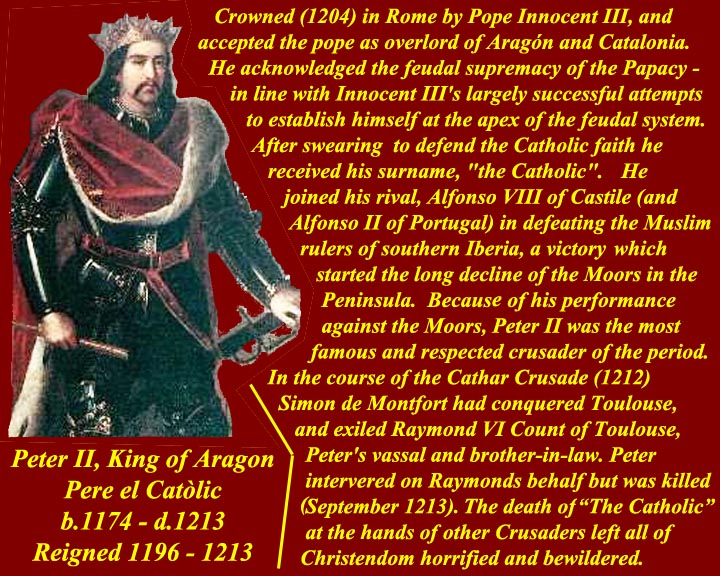

| September 12, 1213 | Battle of Muret: Peter II of Aragon, I of Catalonia comes to the aid of the Cathars in Toulouse and Languedoc who are being harassed by Crusaders. Peter is killed and his army flees. |

| 1214 | Raymond of Toulouse is forced to flee to England. |

| November 1214 | Simon de Montfort entered Périgord captures the Cathar castles of Domme and Montfort. |

| 1215 | The Magna Carta is signed and English barons forced King John to agree to a statement of their rights. |

| 1215 - 1221 | The Fifth Crusade is launched as an attack on Egypt but it ultimately ends in failure. |

| December 14, 1215 | The Fourth Lateran Council accepts the Constitution Ad Liberandum in order to help fund the Fifth Crusade. |

| April 1216 | Raymond of Toulouse and his son, both Cathar heretics, return to southern France, raise a large force from the various Cathar towns that had been captured by the Crusaders, and begin to strike back. |

| 1217 | The Swordbrothers, a Christian army first organized in 1202, invades the region which today makes up Estonia for the purpose of wiping out local pagan beliefs. |

| September 1217 | Raymond of Toulouse recaptures the city of Toulouse from the Crusaders. |

| December 1217 | Armies of the Fifth Crusade attack Mount Tabor. |

| 1218 | Newgate Prison, London's infamous debtor prison, is completed. |

| 1218 | The Swordbrothers begin their conquest of Estonia. |

| 1219 | Pope Honorius III sends Cardinal Pelagius of Albano to the Holy Land to lead the Fifth Crusade. |

| June 03, 1219 | The French town of Marmande falls to the Crusaders. |

| 1220 | During the Baltic Crusade, Conrad of Masovia drives the pagan Prussians out of Chelmno Land. |

| November 22, 1220 | Pope Honorius III crowns Holy Roman Emperor Frederick in the expectation that Frederick would support the Church and participate in the Fifth Crusade. |

| 1222 | Raymond of Toulouse, defender of the Cathars against the Crusaders, dies and his son Raymond takes over for him. |

| 1223 | Pagans from the island of Saaremaa revolt against new Christian leaders, recapturing most of Estonia. They would lose it all again by the next year. |

| 1224 | Amaury de Montfort, leader of the Crusade against the Cathars, flees Carcassonne. The son of Raymond-Roger de Trencaval returns from exile and reclaims the area. |

| November 1225 | Raymond, son of Raymond of Toulouse, is excommunicated. |

| June 1226 | The Crusade against Cathars in southern France is renewed. |

| 1227 |  Medieval

theologian Thomas

Aquinas is born. Aquinas codified Catholic

theology in works like Summa Theologica, marking the

high point of the medieval scholastic movement. Medieval

theologian Thomas

Aquinas is born. Aquinas codified Catholic

theology in works like Summa Theologica, marking the

high point of the medieval scholastic movement. |

| 1228 - 1229 | The Sixth Crusade is led by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, King of Jerusalem through his marriage to Yolanda, daughter of John of Brienne, king of Jerusalem. Frederick had promised to participate in the Fifth Crusade but failed to do so, thus he was under a great deal of pressure to do something substantive this time around. This Crusade would end with a peace treaty granting Christians control of several important holy sites, including Jerusalem. |

| June 28, 1228 | Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen officially (and finally) sets forth on a Crusade. |

| 1229 | The Teutonic Order launches a Crusade to conquer Prussia. |

| 1229 - 1231 | James I of Aragon launches a Crusade in Spain, conquering Valencia and the Balearic Islands. |

| 1229 | Death of Albert, the third Bishop of Buxtehude (Uexküll). Albert had been a major driving force behind the Baltic Crusade. |

| February 18, 1229 | Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen signs a treaty with Sultan Malik Al-Kamil of Egypt and thus acquires controls of Jerusalem. Nazareth, and Bethlehem from Muslim forces. Al-Kamil had been impressed with Frederick's knowledge of Arabic language and culture, leading to a mutual exchange of ideas and respect which allowed the dramatic and unexpected peace treaty to be signed. In exchange, Frederick agrees to support Al-Kamil against his own nephew, al-Nasir. Frederick had been essentially forced to negotiate because at the time he had been excommunicated by Pope Gregory IX and most of the Crusaders in the region (for example, Patriarch Gerald of Lausanne, the Knights Hospitaller, and the Knights Templar) simply failed to obey his commands. Gregory refuses to accept the treaty as valid and doesn't support it. |

| March 18, 1229 | Frederick II crowns himself king of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Conrad IV of Germany had become titular King of Jerusalem the previous year with his father Frederick II as regent. Frederick's wife, Yolanda of Jerusalem and titular Queen of Jerusalem. had died the previous year, so Frederick took the crown for himself. |

| April 12, 1229 | A peace treaty formally ends the Albigensian Crusade in southern France. |

| November 1229 | The Inquisition is established in Toulouse to eliminate the last of the Cathars hiding in the Languedoc region. |

| 1233 | The Inquisition launches a ruthless campaign against the Cathars, burning any that they find and even digging up bodies to burn. |

| 1234 | The Teutonic Knights arrive in the Baltic region to assist in fending off invasions from pagan Prussians. |

| May 12, 1237 | By decree of Pope Gregory IX, the crusading order "The Swordbrothers" is merged into the order,"The Teutonic Knights." Both orders had been heavily involved in Crusades against pagan Prussians; the Swordbrothers, however, had experienced numerous defeats (especially at the Battle of Saule in 1236) and their growing weakness necessitated that they join with the Teutonic Knights. |

| October 1240 | Raymond-Roger de Trencavel is defeated at Carcassonne by Crusaders going after Cathars. |

| April 09, 1241 | Battle of Wahlstatt (Polish: Legnickie Pole): A Crusade against the Mongols is proclaimed after the Teutonic Knights and Henry II the Pious, duke of Poland, are defeated by the Mongols. Mongol leader Batu Khan, son of Ghengis Khan, is only stopped from continuing into the heart of Europe by the news of his father's death, causing him to immediately return home. |

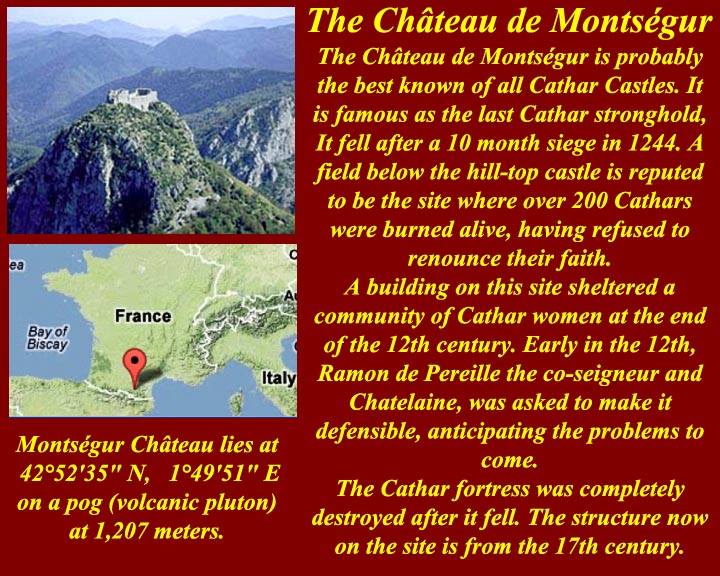

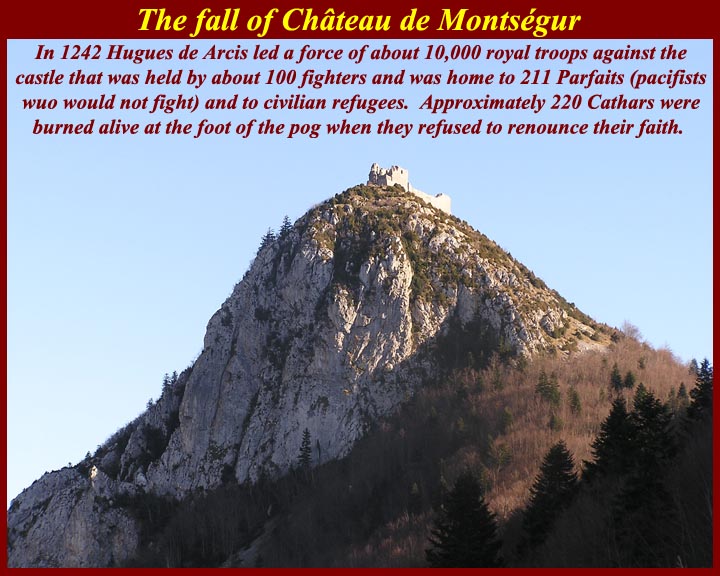

| March 16, 1244 | Montsegur, the largest Cathar stronghold, falls after a nine month siege. |

| 1252 | The Teutonic Knights capture the Lithuanian city of Klaipeda from local pagans. Lithuania would be access to the Baltic Sea until the 20th century. |

| 1253 | Pagan leader Mindaugas of Lithuania agrees to convert to Christianity. |

| 1255 | The Teutonic Knights build their stronghold of Königsberg. |

| May 1255 | The last Cathar stronghold - an isolated fort at Quéribus - is captured. |

| 1260 | Battle of Durbe: Lithuanians defeat the Livonian Teutonic Knights |

| 1263 | Mindaugas, first and only Christian king of Lithuania, is assassinated by his pagan cousin Treniota. |

| 1284 | The Teutonic Knights complete their conquest of Prussia, eliminating the local Prussian population as an independent ethnic group. The Prussians would be assimilated by the Germans, Poles, and Lithuanians while the Prussian name would be adopted by the Germans for themselves. |

| 1309 | The Teutonic Order moves its headquarters to Marienburg, Prussia. |

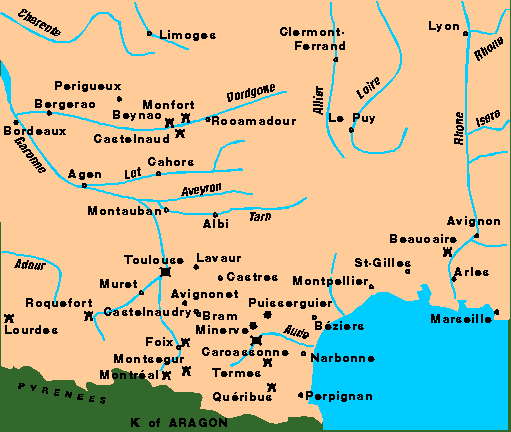

The Albigensian (Cathar) Crusade

From http://xenophongroup.com/montjoie/albigens.htm

c.f., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albigensian_Crusade

CATHARISMFrom the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries a religious sect called 'Cathars' spread to parts of Europe. The word 'Cathar' is derived from the Greek 'Katharos' (meaning 'pure'). The German word 'Ketter' (meaning 'heretic') was obviously influenced from the Cathars in southern medieval Europe, as the sect was so perceived by the official Roman Catholic Church at the time. The Cathar sect held an austere belief that renounced worldly pleasures, seeing such as destructive temptations provided by an evil deity (the Devil). It believed that a second, good deity (God) created parfaits ('pure souls') that were being corrupted by the material and the pleasures of the natural world they found themselves in. Those of the Cathars who were recognized as parfaits made up the elite, and relatively small leadership of the sect, that practiced extreme asceticism and did not marry. The parfaits held strong sway over the the much larger following refereed to as croyants ('believers'), who were permitted to have families. However, even these were expected, before they died, to undergo a consolamentum, a form of 'baptism' that transformed a soul back to its pure state. Though they thought of themselves as Christians, the Cathars were very opposed to the authority, teachings and clergy of the Roman Catholic or Greek Orthodox churches.

The Cathars were particularly strong in southern France, in the region known as Languedoc, where the language of Oc was spoken as opposed to the French language used in northern France. The northern French called the Cathars 'Albigensians' because of the strong representation of the belief's adherents in the town of Albi.

POLITICAL STRUCTURE of LANGUEDOC

Languedoc is the name of an historic region in the central southern part of what is modern France. It has no unity other than a shared spoken language called langue d'oc. The language of oc was a corruption of Latin mixed with words of various invaders that passed through. The language in this central southern area of France was closer to the older Latin than the French language spoken in northern France (langue d'oil -- especially north of the Loire), which was tinged with some Germanic influences.

Political boundaries in early medieval Languedoc were mostly defined by association with nearby strong fortresses, which might be a walled town or merely a castle. The feudal system was weaker than in northern France, and the local lords maintained considerable independence. Many towns were controlled by councils. Contributing to fragmented political unity in the region were the incursions of the comtes de Barcelona. This powerful ruling house in Catalonia had been acquiring fiefs to the north of the Pyrenees from the early twelfth century. There were other 'foreign' pressures upon Languedoc. To the west was Aquitaine, its duke was technically a vassal to the king of France, but he was also the king of England. To the east, some territories in Provence were considered properties of the Catholic pope as well as of the Emperor of the Germans.

The most prominent counties in Languedoc were Toulouse, Foix, and Comminges. Of equal prominence were the vicounties of Trencavel. The comte de Toulouse, Raymond IV, was also count of Provence (east of Languedoc). His domain encompassed an area of particular active trade and commerce. The wealthy lords of the counties and vicounties in this area lived well, and they allowed an atmosphere of relatively open mindedness and tolerance of beliefs. The Roman Catholic parishes were not as strong a community focal point as they were in many other parts of France. Jews and Cathars served in many of the courts of the comte de Toulouse and the vicomte de Trencavel, the latter was very open in his support of the Cathars.

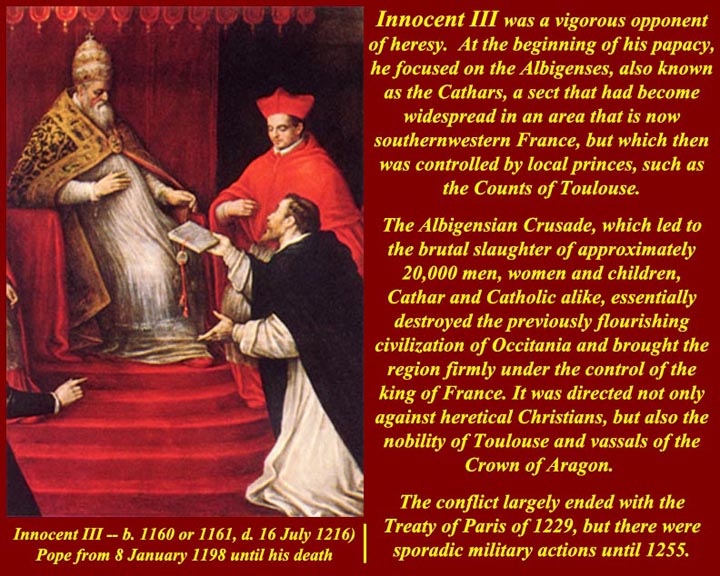

CRUSADE CALLED

Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) was concerned with the growing influence of Catharism, and saw that it threatened the authority of the Church. He saw the movement as a heresy that needed to be eliminated, as were Arianism and Manichaenism in earlier times. In 1204, Innocent III tasked Abbot Arnaud-Amaury [Arnold-Amalric], head of the Cistercian Order, to be a special legate to investigate Catharism in Languedoc. The papal legate used the cloister in the monastery of Fontfroide as his main outpost. Some regular clerics were also sent by the pope. One from Spain was Domingo de Guzmán, the future St. Dominic and founder of the Dominican Order. Domingo attempted to apply the Cathar's austere methods in his promotion of orthodox Christanity, and he had some success in converting a few Cathars. The progress was inadequate, and the Church decided to use force to either convert or to eliminate the declared heretic followers of Catharism.

The pope asked Philippe II Auguste, the French king (and a cousin to comte Raymond VI de Toulouse), to take action against high nobles in southern France who permitted Cathars to openly practice their faith. Philippe II did not comply, as he was facing a more direct threat from an alliance of the English king, Flemish nobles and the German Emperor.

In 1206, the pope's legate, Amaury, sent his assistant, another Cistercian monk, Pierre de Castelnau, to Provence to form a league of knights to fight Catharism. Castelnau invited comte Raymond VI of Toulouse to lead this host. Raymond saw no value in such a campaign against this community that was widely spread and well ingrained in his lands. He rejected the "idea of waging war on his own subjects," and Castelnau called for Raymond VI's excommunication. The pope ratified the excommunication of Raymond in May 1207. On 13 January 1208, Raymond met with Pierre de Castelnau at Saint-Gilles, in Provence. The monk and Raymond argued and exchanged threats.

The next morning (14 January), Pierre de Castelnau was assassinated as he was departing the town. His assassin was believed to have been an agent of comte Raymond VI. Pope Innocent III reacted by proclaiming a crusade against the 'sinister race' of Languedoc. His Bull offered indulgences for combatants declared that the heretics' lands were open to be taken. This latter offer enticed many knights from far who needed, or merely sought more land.

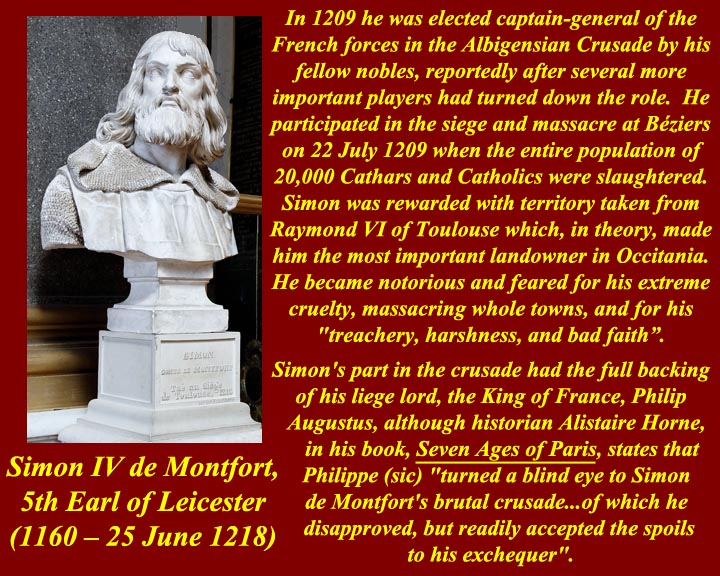

One such French knight was Simon IV de Montfort l'Amaury, (1165-1218), who was disinherited from his uncle's estates of Leicester, in England, by king John I in 1207. Simon IV was a minor lord in the Chevreuse Valley (in the modern Seine-et-Oise region) of France. He had departed with in the Fourth Crusade in 1202, but refused to participate in the attack upon Constantinople instead of Jerusalem. The pope's offer of confiscated lands inspired Simon IV de Montfort to go south with many other northern French knights in the crusades against the Cathars.

EVENTS of the FIRST PHASE: SIMON IV de MONTFORT's CONQUEST

1209 June, an 'army' of crusaders gathered in Lyon. The number was probably between 10,000 and 20,000 [some accounts estimate over 100,000]. Besides Simon IV de Montfort, there were the duc de Bourgogne, the counts of Nevers and Saint-Pol, the Seneschal of Anjou, and numerous other noblemen. This host marched south, along the River Rhone towards Provence. They were joined by Arnaud-Amaury, the papal legate who had a titular leadership position as 'spiritual advisor' in the 'holy' campaign.EVENTS of the SECOND PHASE: LANGUEDOC REVOLTS (1215-1225)

Meanwhile, comte Raymond de Toulouse recognized the serious situation developing and sought to be reconciled with The Church. In June, he returned to Saint-Gilles, stood barefoot before Pierre de Castelnau's sepulcher, and pledged to expel Cathars from Toulouse. The pope lifted his excommunication, and Raymond VI tentatively joined the crusade. The crusaders marched to Montpellier, (which, should be noted, was a fief of the King of Aragón).

Raymond-Roger III de Trencavel (age 24/25 and nephew of Raymond VI de Toulouse) realized that the crusaders were heading for his lands. Though he was a Roman Catholic, Roger de Trencavel tolerated particularly strong Cathar concentrations in his viscounties of Carcassonne and Albi. He met with the religious 'commander' of the crusade, Arnaud-Amaury, at Montpellier, to 'surrender to the Church'. However, Amaury refused to receive Roger de Trencavel. Knowing that his lands were to be attacked, Raymond-Roger deTrencavel quickly returned to Carcassonne to organize his defenses.

Servian

Early July 1209, Simon de Montfort captured the hilltop village of Servian, to the east of Béziers, prior to going to Béziers.

Béziers

On 21 July, the crusaders reached Béziers and demanded that the Cathars in the population be handed over. This was refused even by the Roman Catholics of the town. The tradition of Cathar strength in this town went back to 1167, when they murdered their vicomte, Raymond-Roger I de Trencavel, in revenge for one of his knights having killed a Cathar. In return the vicomte's son, Raymond-Roger II, had the town ransacked in 1169. Domingo de Guzmán and Pierre de Castelnau had attempted to confront the population in 1206.

On the afternoon of 22 July, the town launched a sortie which, when forced back into the town, was closely pursued by a band of the crusaders. Once inside the walls of the town, the crusaders seized Béziers within an hour. Immediately there began a mass slaughter of Catholics and Cathars, alike. When asked by one of the crusader warriors about the possible killing of Catholics along with the heretic Cathars, Arnaud-Amaury is supposed to have delivered his nefarious statement "Kill them all! God will recognize His own!" Accounts vary as to the numbered slaughtered (10,000 to 20,000, with just over 200 estimated to have been Cathars) in this, the bloodiest and first, battle of the crusade. The massacre frightened many other towns to surrender without resistance.

Present among the crusaders was a Cistercian monk, Pierre des Vaux-de-Cernay, who ten years later would write his chronical Historia Albigensis of the campaign.

Puysserguier

In autumn of 1209, Guiraud de Pépieux, lord of a small estate between Carcassonne and Minerve, rallied to the crusaders' camp after the fall of Béziers. Later, he revolted and captured Puysserguier castle and took prisoner two of the knights who guraded the fortress. By the time Montfort arrived with aid, Guiraud had departed with his captives for Minerve. Out of revenge, Guiraud mutulated his prisoners (blinding them and cutting off thier noses and upper lips) and sent them naked in the cold to Carcassonne.

Carcassonne

Carcassonne was the next objective of the crusaders. They arrived before the impressive fortifications on 1 August 1209. The town's population was bloated with many Cathars and others who had fled the northern French crusading host. This perceptively impregnable fortified city of 26 [30?] towers sat above the Aude River. Its vunerable point was that it relied on access to the river for its water supply.

Pedro II d'Aragón, a Catholic monarch, who had won considerable fame in fighting the Moors in Spain, was a protector of the Trencavels [and brother-in-law to Raymond VI de Toulouse], came to Carcassonne and tried to mediate. Arnaud-Amaury continued to refuse giving any quarter in the crusade, and Pedro II departed in anger. The siege proceded with the both sides employing trebuchet and mangonel rotating-beam artillery, along with other large siege machinery. However the most effective tactic was the crusaders' capture of two faubourgs outside the walls, the first on 7 August. This effectively cut off the Carassonne defenders' access to the river.

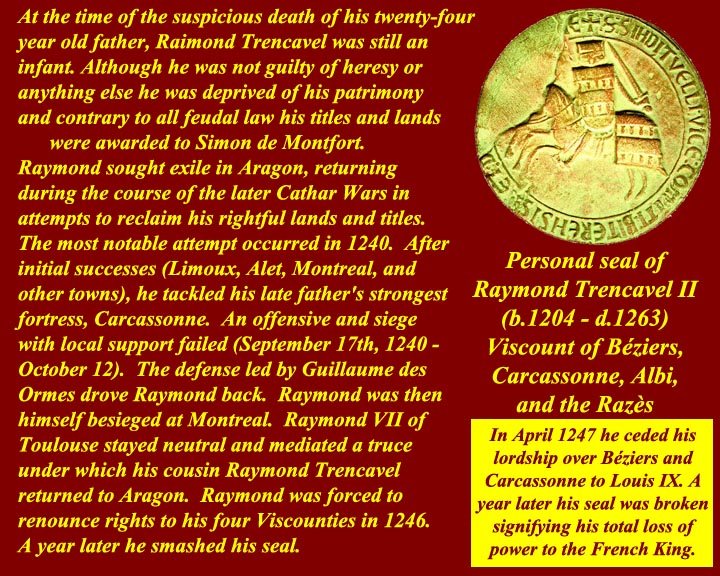

Thirst and spreading disease forced Roger de Trencavel to seek negotiations for surrender. While supposedly under 'safe-conduct', he was made prisoner. Carcassonne surrendered 15 August 1209. Raymond-Roger III de Trencavel died in one of the fortress dungeons on 10 November. Montfort's crusaders did not conduct a massacre, but forced the residents of Carcassonne to to depart the walled city, "taking nothing but their sins." Roger III de Trencavel's wife and young son (Raymond-Roger IV) took refuge with the comte de Foix, whose sister, Esclarmonde, was a Cathar.

Simon de Montfort sought suzerain status over Carcassonne, Albi, Béziers and the Razès area. The other senior French lords of the crusade were not interested in possessing such contentious lands. Most, like the comtes de Nevers and Saint-Pol returned to their northern domains by autumn of 1209. The duc de Bourgogne remained through September at Carcassone with about 300 men. He tried and burned two Cathars in October 1209.

Towns such as Castelnaudary, Fanjeaux, Montréal, Limoux, Castres, Albi or Lombers surrendered without a real fight. Montfort pushed beyond the Trencavel vicomtes and attacked lands of the comte de Foix (Mirepoix, Foix and Saverdun). However, some the towns revolted against Montfort: Castres, Lombers, Montréal, etc. Cathari and 'faidits' (lords who dispossessed of their lands) took refuge in Minerve, Termes or Cabaret and launched counter attacks against what was left of Montfort's army.

In December 1209, de Montfort was recognized by Innocent III as a direct vassal of the Roman Pope.

Lastours-Cabaret

Late in the year, Simon and the duc de Bourgogne attacked Lastours, a city nine miles north of Carcassone, where Pierre-Roger de Cabaret (a vassal of the Trencavel's) harbored many fleeing Cathars. Lastours-Cabaret was a system of four 'castles' [Cabaret being the lord's residence, Lastours the main citadel stucture, the other two being simple towers] close enough to provide cover for one another. It was a formidable stronghold that permited Pierre-Roger de Cabaret to repulsed the attack. In a raid, de Cabaret took captive Montfort's lieutenant (and cousin) Bouchard de Marly, lord of Saissac.

1210 During winter, Arnaud-Amaury took over and was elected archbishop of comte Raymond VI's port city of Narbonne. The costal town became a major entry for crusaders' supplies and additional men. New venturers came from Anjou, Frisia, Lorraine, Bavaris, Gascony, Champagne, Brittany, Flanders, Normandy, Aquitaine, and numerous parts of Europe.

Bram

In March 1210, de Montfort captured Bram in a 3-day siege. He mutulated 100 of his captives and sent them to Pierre-Roger de Cabaret, at Lastours.

Minerve

In June 1210, the crusaders arrived before the impressively positioned (flanked by deep gorges) fortress of Minerve. They brought four siege machines (trebuchets and/or mangonels), which, along with their sizable stone shot, had to be positioned in the mountains surrounding the town. The fortress town was commanded by Guilhem de Minerve. Though he was not a Cathar, he felt compelled to support his lord de Trencavel. The intense bombardment managed to destroy the staircase to the otherwise secure water well. On 27 June, a number of the besieged population made a night sortie and set fire to the machine, which they named 'Malvoisine' and believed had destroyed their well. Thurst forced Minerve to surrender on 22 July. Arnaud-Amaury refused any negotiated terms. Three women of the town agreed to convert and were spared. Reportedly 140 Cathars who refused to abjure their faith died at the stake. This was the first burning at the stake in the crusade.

Termes

In early August, de Montfort began his siege of Termes, whose lord was a devoute Cathar. However, he was hampered by Pierre-Roger de Cabaret raiding his wagon rain. One attack seriously damaged the wooden siege engines. In another attack, Pierre-Roger decimated Montfort's rearguard and mutilated those captured as a response to what Montfort had done to his captives at Bram. The siege lasted until December, when the defenders ran out of water. The Cathar lord was placed in the Carcassonne dungeon, where he eventually died.

1211 Arnaud-Amaury remained relentless in his goal to eradicate the heretics. In January 1211, he accused several prominent citizens of Toulouse as heretics. When Raymond VI refused to prosecute them, he was again excommunicated by Arnaud-Amaury.

Pedro II d'Aragón was present when Arnaud-Amaury presented his ultimatum to Raymond VI, and expressed his resentment of the outragous demands and actions of the crusaders. Raymond VI was encouraged with the Aragón king's support and began to organize a coaltion of neighboring lords (comtes de Foix and de Comminges) who were threatened by the obvious land-grabing of Montfort.

Lastours-Cabaret

With the arrival of a new host of crusaders from northern France in March 1211, Montfort was able to significantly threaten Pierre-Roger de Cabarat's formidable Lastours-Cabaret defense complex. Pierre-Roger agreed to free Bouchard and surrendered his fortresses in exchange for some land in Béziers.

Lavaur

In May, de Montfort attacked and quickly seized Lavaur, the castle of Aimery de Montréal, a lord who had revolted against Montfort. Aimery and his knights were hung and about 300 to 400 Cathars burned. Aimery's sister, Giralda de Laurac, was reportedly turned over to be abused by Montfort's soldiers before being thrown in a well and stoned to death.

During Montfort's attack on Lavaur, the comtes de Foix and Comminges managed to attack a host from Germany that was coming to join the crusaders.

Cassès

This was quickly taken in early June, and about fifty Cathars were burnt.

Montferrand

This small fortress was surrendered by Raymond VI's brother, Beaudouin, who soon after joined the ranks of the crusaders as he turned over the castle, Bruniquel, to Montfort.

Toulouse

In June, Montfort, reinforced with a large contingent from Germany, led the crusaders to besiege Raymon VI's principal town, Toulouse. It was a fromidable walled city and had also been reinforced with warriors from Commings and Foix. Montfort fended of some sorties from the city, but eventually (29 June, after two weeks of siege) had to pull back to replenish his force.

Castelnaudary

In September, Raymond VI de Toulouse and Raymond-Roger de Foix led a sizable force [possibly about 10,000] to besieged Montfort at Castelnaudary. Montfort's forces had again begun to dwindle, as the varied venturers were not finding the crusade to be very rewarding. However, Montfort was served by a hardcore of warriors, and Raymond VI de Toulouse was not the ablest of commanders.

Raymond-Roger de Foix engaged a relief force, led by Bouchard de Marly, heading to Castelnaudary. The encouter was about three miles from the fortress and Montfort abandoned the defense of Castelnaudary to assist the relief party. His arrival managed to turn the tied of the battle and led to a defeat of Raymond-Roger's army. However, Montfort was not strong enough to try and prevent Raymond VI de Toulouse seizure of Castelnaudary. Raymond VI was able to go on and to captured about sixty fortresses or towns held by Montfort's crusaders.

Lastours-Cabarat

In autumn of 1211, Raymond VI tried unsuccessfully to retake Cabaret.

1212 In April, de Montfort was reinforced with another crusading host, which he led in a series of lightening strikes throughout Toulouse.

1213 In September 1213, Pedro II d'Aragón led an army to Toulouse with, and joined forces with Raymond de Toulouse and the comtes de foix and Comminges. It was little over a year after Pedro II had shared the honors in the epic victory over the Almoravid sultan at Las Navas de Tolsa (16 July 1212) in Spain. Pedro II had long resented de Montfort's incursion upon some of his fiefs, and now felt compelled to act against de Montfort's aggression.

Muret

Pedro II besieged Muret, one the castles de Montfort now held. The comtes de Foix and Comminges joined him immediately. Raymond VI was enroute with a large siege train, when Montfort joined his besieged garrison on 11 September.

Pedro II launched an attack on 12 September. It was repelled, and quickly followed by a daring sortie by de Montfort that forced Pedro II's army to engage in a unexpected melée. Pedro II was killed in the action, and his army panicked. De Montfort won a descive victory.

1214 Pope Innocent III appointed a new legate to replace Arnaud-Amaury. The comtes de Foix and Comminges took the opportunity to submit to the new legate in April 1214. Raymond VI was helpless to put any more resistance. He fled to England as the pope proclaimed that Toulouse was proclaimed to be a fief of the king of France, Philippe II, who heretofor had been disinterested in the campaign.

Philippe II's interest changed following his great victories over the English king John I's attempted invasion into southwest France and then over the German Emperor, Otto IV, at the battle of Bouvines (27 July 1214) in northeastern France. This climatic event freed the French monarach to consider acquiring the regions to the south of his principal domain.

Campaign along the Dordogne

In November, 1214 Simon de Montfort advanced to the northern borders of Languedoc and into Périgord, taking some castles along the Dordogne River. The region was a stronghold of Bernard de Casnac, a bold Cathar military leader. Domme castle, a Cathar stronghold was abandoned before de Montfort arrived. Next was Montfort [no relation to Simon de Montfort] castle, which also had been abandoned before de Monftort approached.

Castelnaud and Beynac

Montfort continued along the Dordogne to the impressive fortified castles of Castlenaud and Beynac, each on opposite sides of the river only a short distance apart. De Montfort found Castlenaud empty and placed a garrison in it, as he proceded to Beynac. Beynac was not owned by Bernard de Casnac, nor was it a Cathar position. De Montfort attempted to demolish the fortifications, but did not harm the people, who were under the protection of the king of France. The Dordogne operations marked the northern limits of the Albigensian wars.

1215 King Philippe II sent his son, prince Louis [future Louis VIII] to accompany de Montfort when the latter entered Toulouse in May 1215.

In autumn, at the Fourth Lateran Council, the pope confirmed de Montfort's right to Toulouse. Raymond VII's rights to Provence were not affected, which meant that it remained an inheritance reserved to Raymon VI's eldest son, eighteen-year-old Raymond VII. However, the ten-year-old Raymond Trencaval, son of the deceased Raymond-Roger de Trencaval was disinherited the viscounty Trencaval lands.

Castelnaud

Early in the year, Bernard de Cazenac seized back Castelnaud and killed the garrison de Montfort had left. In October, de Montfort conducted a swift expedition back into Périgord, recapturing the castles and killing all the Cathar defenders. Bernard de Cazenac managed to avoid capture and continued to engage de Montfort.

1216 In April 1216, de Montfort paid homage to Philippe at Paris for his lands, ceding his conquests to the French sovereign. However, resentment rose in the Languedoc region, which welcomed the return of Raymond VI and his 19 year old son, Raymond VII, at the port of Marseilles in April 1216. Many towns rallied to their side. Particularly Avignon, which was within the domain of the comte de Provence and a dependent of the German Emperor. Avignon contributed troops for the capture of Beaucaire, Raymond VII's birthplace in 1197.

BeaucaireEVENTS of the THIRD PHASE:

De Montfort had installed some troops under Lambert de Thury, at Beaucaire, even though the it was in Provence, and outside his rightful lands. Raymond VII besieged the French garrison at Beaucaire in May 1216. His father, Raymond VI, sought reinforcements from Aragon. Simon IV de Montfort rushed to relieve the town. The French crusader garrison held for three months before they ran out of food. After failing in many costly attacks, de Montfort was forced to negotiate the surrender of the castle on conditions that the defenders could leave. It was de Montfort's first major defeat.

Immediately after this reverse, de Montfort rushed to put down another revolt at his capital city of Toulouse. Following this, he went to fight in Bigorre, and met another defeat at Lourdes, at the end of 1216. Lourdes, in the Hautes-Pyrenees, marked the western limit of the Albigensian crusade that pertained directly with the Cathars.

1217 De Montfort proceeded to campaign in the county of Foix. He captured Montgrenier in Feb/March 1217. His campaign reached in to the Corbières area, and as far as the Drôme Valley. Meanwhile, Raymond VII took advantage of Montfort's absence and led a large Aragonese host crossed the Pyrenees and entered Toulouse on 13 September 1217. De Montfort returned and attempted a siege. However, his forces were inadequate and he needed to build a siege train for the town's defense structure remained strong, even though de Montfort had directed it be brought down when he controlled it and had to contend with revolts inside the city.

1218 Toulouse

Starting in spring, de Montfort prepared his siege of Toulouse. In June he brought in a cat, a mobile cover to protect sappers as they approached the wall of the fortress. On 25 June, the defenders disabled the device with their mechanical artillery (rotating-beam trebuchet and/or mangonels firing from within the fortress-city walls) and then sortied out to burn it. De Montfort led a counter attack against the defenders' sortie. During this encounter, Simon de Montfort paused to aid his brother, Guy, who was wounded by crossbow bolt. At that moment, a stone from the defenders' artillery struck Simon de Montfort's head and killed him. The shot was fired by a rotating-beam artillery machine, and reportedly was crewed by women.

The circumstances of de Montfort's death emphasizes the significant role of mechanical artillery in the siege-intensive military operations of these crusades. An explanatory note on the topic can be found at the end of this webpage.

The death of Simon IV de Montfort dramatically changed the nature of the 'crusade'. There was no high noble ready or available to take his place as leader. By default, it remained for the king of France to continue the struggle, which now was not so much to seek and to destroy heretics as to fight for possession of the county of Toulouse.

Raymond VII de Toulouse and the comte de Foix took advantage of the disarray among the crusaders. They defeated an army of northern French knights at Baziège. The new pope, Honorius III (since the death of Innocent III, July 1216) asked the king of France to assist Simon's 26 year-old son and heir, Amaury de Montfort. Philippe II Auguste sent Prince Louis, for a second time. However, Louis' expedition was very circumspect, as his father waited for the confusion in Lauguedoc to settle down.

Belcaire

Belcaire, a refuge for Cathars, was besieged in 1218.

1219 In early 1219, Raymond VII and the comte de Foix defeated a band of crusaders in one of the few open battles of the war, at Baziège.

Marmande

In June, Prince Louis joined with Amaury de Montfort's force, which had been besieging Marmande since December 1218. The town surrendered, and the entire inhabitants [possibly 5,000] were 'massacre' on 3 June 1219.

Louis joined the crusaders to besiege Toulouse on 16 June. However, the prince suddenly withdrew, and returned to northern France in August 1219. Amaury de Montfort continued to suffer a series of defeats, as many of de Montfort's garrisons quickly surrendered to Raymond VII.

1220 Castelnaudary-2

Raymond VII captured Castelnaudary. During the attack, Guy de Montfort (Simon's second son and Amaury's younger brother) was killed. Amaury de Montfort was never able to recaptured the town during an eight-month of siege (July 1220-March 1221).

1221 Montréal

In February, Raymond IV and Roger-Bernard de Foix recaptured Montréal. During the attack, the local lord, Alain de Rouey, who had killed Pedro II of Aragón at the battle of Muret, was mortally wounded.

Montréal was supposed to be where the 'miracle of Fanjeaux' occurred (1207). In an 'ordeal by fire', a Cathar parchment was burnt and St Dominic's parchmant flew up to the rafters and schoched the roof. Fanjeaux is a nearby town where St. Dominic (d.1221), was a priest for a short time. It became a crusader's headquarters, and was attacked and burnt by the comte de Foix.

As Raymond VII and his vassals gradually recaptured their lands, Catharism resurfaced, and many Catholic bishops to fled.

1222 Both Amaury de Montfort and Raymond VII offered sovereignty of the county of Toulouse to Philippe II Auguste, who refused it.

Raymond VI died in July 1222 and was denied a Christian burial by the Church. His son, Raymond VII, who had been the realy dynamic force in the recent campaigns, became the comte de Provence and the disputed land of Toulouse.

Alet

Alet was handed over to comte de Foix by Father Boston.

1223 Roger-Bernard de Foix and Philippe II Auguste of France died. Philippe II's son, Louis VIII initially remained remote from any strong support of Amaury de Montfort.

1224 Carassonne

In January, Amaury de Montfort abandoned Carassonne and retreated to northern France with the remains of his father, Simon IV. He offered the 'conquered lands' to the new French monarch, Louis VIII.

The 18 years old son the of the vicomte Raymond-Roger III de Trencaval (who had died in the Carcassonne dungeon in 1209) returned from exile, and entered his father's former capital city as Raymond-Roger IV de Trencaval. After fourteen years of massacres and people being burnt at the stake, the situation was almost back to where it was 1209. At this point, the crusade had failed. Appropriately for the year 1224, Arnaud-Amaury died, not suprisingly a bitter and disillusioned individual.

Unlike his father (Philippe II), King Louis VIII was ready to expand the Royal domain with the bounty from the Albigensian affair. He accepted the offer of Amaury de Montfort. However, pope Honorius III (who was not eager to have a stronger presence of the French in Languedoc) had to be persuaded by the bishops in southern France to continue supporting a crusade.

CONQUESTS of LOUIS VIII, BLANCHE de CASTILLE, and LOUIS IX (1225-1229)

1225 Raymond VII de Toulouse was excommunicated when he attended the Council of Bourges (November-December of 1225).

1226 In late June, Louis VIII personally led a new crusade into Languedoc. Most of the castles and towns surrendered without resistance. Raymond VII, Roger-Bernard de Foix, Raymond Trencaval and a number of 'faidits' were alone in resisting the Royal campaign.EVENTS of the FINAL PHASE: INQUISITION and the CATHAR's LAST GASPS

Avignon

As a fief of the German Emperor, Avignon, refused to open its gates to the king of France when he came before it on 6 June. After a siege of three months, the city capitulated 12 September 1226. As most all Languedoc submitted, Toulouse prepared to resist alone.

Carcassonne

On 16 June, Carcassonne surrendered to Louis VIII.

Louis VIII became ill, and died in Auvergne on 8 November 1226 as he was returning to northern France. He left his seneschal, Humbert de Beaujeu, to continue the crusade. Blanche de Castille, the regent for her son Louis IX, confirmed Beaujeu's position. Humbert de Beaujeu conducted the crusade until Louis IX was old enough to take over.

1227 Labécède

Labécède was besieged by Humbert de Beaujeu and the bishops of Narbonne and Toulouse. Pounded by siege machines and set afire, the entire town was reportedly massacred.

1228 Guy de Montfort, brother of Simon de Montfort and uncle to Amaury, had returned to Languedoc to defend what was left to the Montfort's claims. He was killed besieging Vareilles in January 1228.

Toulouse was starved in the summer. Bernard and Oliver de Termes surrounded in November 1228.

Blanche de Castile decided to negotiate. She agreed to recognize Raymond VII as the legitimate owner of the county of Toulouse (and vassel of France) if he married his only daughter, Jeanne (then 9 years old), to her son, Alphonse of Poitiers (also 9 years old and brother to the young Louis IX).

1229 In the 'Treaty of Paris', Raymond VII agreed to Blanche's terms on 12 April 1229 at a meeting in Meaux. [The treaty is sometimes given the name of this town.] Raymond VII agreed to fight the Cathar 'heresy', to return all Church properity, to demolish the defenses of Toulouse, and to turn over all his castles, as well as pay damages. Raymond VII was flagelated and humulated on a parvis in front of Notre-Dame, and then imprisoned. His wife was expelled from Toulouse. This marked the end of independence in Languedoc.

More frightening was the establishment of the Inquisition at Toulouse in November 1229. The treaty ended the political part of the crusade, but the religious struggle and the campaign for the Cathar fortresses continued.

1233 Pope Gregory IX supported the Dominican-run Inquisition, allowing it limitless powers to torture and burn heretics at the stake. The institution was established in Languedoc in April 1233. Cathati were ruthlessly sought out. As expected, many resisted and took refuge in castles of viscouny of Fenouillèdes or in Montségur. Sick, eldery, and even exhumed bodies were burned. The Inquisition's gruesome excesses incited revolts that continued for many years in Narbonne, Cordes, Carcassonne, Albi, and Toulouse.

1235 Popular uprisings against the Inquisition occurred in many areas of Languedoc in 1235. The Dominicans were expelled from Toulouse. An inquisitor was thrown into the river Tarn at Albi. At Cordes, the inquisitors were thrown down a 100 foot well to their deaths. By autumn, the inquisitors had been run out of Toulouse, Albi, and Narbonne.EPILOGUE

1240 Raymond-Roger IV de Trencavel led a final revolt. He raised an army and traveled from the Cobières region to win a few victories. He was defeated at Carcassonne on October 1240. Forced to begin negotiations in Montréal [after 34 days of siege], he retired to Aragón with the remnant of his army. The French army, under Jehan de Beaumont, entered the Fenouillèdes. Peyrepertuse, the largest of the Cathar fortresses, surrendered to Beaumont 16 November 1240 after a three-day siege.

1242 Raymond VII de Toulouse tried to clear himself of the insult he had suffered in Meaux. He obtained support from the kings of Castile, Aragón, Navarre, and England. He led an insurrection in May 1242. A small force set out from Montségur to attack and massacre several members of the Inquisition in Avignonet (28 May). Raymond's campaign attempted to take advantage of an invasion by the English king, Henry III, into southwestern France.

Louis IX swiftly defeated the English king Henry III at Saints and at Taillebourg in July 1242. Raymond VII's allies fell away as they saw the French king prepare for a massive campaign into Languedoc.

1243 Again, Raymond VII was compelled to submit to the French king in January 1243. The ceremony took place near Montargis. Though Louis IX pardoned Raymond VII, the Roman Catholic Church did not. Remembering the killings at Avignonet, Raymond VII remained excommunicated.

Montségur

The crusade to wipe out Catharism continued, and the followers were driven to the security of a few strong fortresses. One was Montségur, sitting 400 feet above the surrounding plain [current structure is a reconstruction, built upon the original site]. It had a barbican on a lower plateau to the west . The lord of Montségur and his son-in-law, Pierre-Roger de Mirepoix, held strong Cathar sympathies. They were supported by eleven knights and about 150 soldiers. Including the warriors' families, the fortress contained about 500 people.

In early May, Hugues des Arcis arrived at Montségur with 1,500 men, expecting to starve the defenders out. In November, Hugues des Arcis sent some lightly armed men to scale the precipitous eastern slope. In a daring night ascent, they acquired a foothold and began hoisting up siege machines. They finally began shooting [lobbing] stones upon the barbican to the fortress.

1244 In February 1244, Hugues des Arcis captured the barbican to Montségur. The defenders surrendered at the end of month. The fortress, called by non-Cathars 'Satan's synagogue', was emptied on 16 March, and 210 Cathars were burned in a fire at the base of the mountain.

1249 Eventually, Raymond VII assisted the Inquisition in a further effort to clear his name. He cooperated in the burning of some people at the stake in Agen in 1249. Raymond VII de Toulouse died the same year, as he was preparing to join Louis IX on the Seventh crusade. Jeanne, his daughter, became comtess de Toulouse. When she and her husband (Alphonse de Poitiers) died childless in 1271, the county of Toulouse became part of the Royal domain of France.

1255 Quéribus

The final military action in the epic 45-years' crusade was a siege of the small Cathar fortress of Quéribus. It fell in August of 1255. This remote refuge was never attacked until 1255, when Louis IX requested the seneschal of Carcassonne, Pierre d'Auteuil, to seize it from Chabert de Barberia.

The fall of Quéribus in 1255 marked the last dramatic military operation of the crusades against the Cathars. An earlier date of 1229 is often used, since it marked a 'political' resolution with the Treaty of Paris [also called Treaty of Meaux]. However, there remained a few loose ends.BIBLIOGRAPHY

Raymond VII's daughter, Jeanne, became comtess de Toulouse upon her father's death. She and her husband, Alphonse de Poitiers, died without heirs in 1271. As arranged in the 1229 treaty, Toulouse was annexed to the king of France.

Incidents of Catharism re-surfaced in the fourteenth century. Pierre Authié attempted, but failed, to introduce the belief in Languedoc. Guillaume Bélibaste was reportedly the last known Cathar to have been burned at the stake in 1321. Some may detect traces of sympathy with the Cathar's movement evidenced in the much later, strong receptivity of Protestantism in Languedoc -- if only as a rejection of the Catholic Church's authority. Some bemoan the loss of the distinctive troubadour and relatively tolerant culture of the twelfth-century Languedoc. However, this was probably more affected by the later impact of the Hundred Years' War.

Amaury de Montfort retired to his modest estate in Ile-de-Fance, and went on to serve the king. He was made constable of France in 1230, and joined a crusade to the Levant, where he was captured. He was released after 18 months, and died at Otranto, Italy (1241), as he was returning to France.

His younger brother, Simon, was Simon IV de Montfort l'Amaury's youngest son and also named 'Simon'. The younger Simon de Montfort left France for England, where the king, Henry III, restored Simon (as 'earl') to his ancestral lands in Leicester and married him to his sister. Simon later fell out with the king and sided with the barons in a reform movement. He died fighting the royal forces at the battle of Evesham (1265).

- Aimer le pays cathare

- Jean-Luc Aubarbier. 1992. A 1994 edited version, in idiom from Périgord, is the French text and basis for the following listed work.

- Wonderful Cathar Country

- Jean-Luc Aubarbier, Michel Binet, Jean-Pierre Bouchard; English translation by Angela Moyron. Editions Ouest-France, Rennes, 1994. Profusely illustrated with color photographs and descriptions to guide visits to the various sites as they exist today.

- Le Drame albigeois et le Destin français

- Jacques Madule. Bernard Grasset, Paris, 1961. English translation by Barbara Wall, The Albigensian Crusade (Fordam U., NY, 1967). A fine concise account and analysis of the epic as it related to the development of France. However, it lacks supporting citations.

- The Albigensian Crusade

- Jonathan Sumption. Faber, London, 1978 and 2000. A scholarly, comprehensive, and very readable narrative account in English.

- The Albigensian Crusades

- Joseph R. Strayer. Dial, New York, 1971; re published with an added Epilogue by Carol Lansing that explores aspects of the Cathar 'heresy' (U. of Michigan, 1992).

- Historia Albigensis

- Pierre des Vaux-de-Cerny. Edited by P. Guébin and E. Lyon, 3 vols., 1926-39. A young monk who was eyewitness to much of the crusade until 1219. An English translation, with notes, by W.A. and M.D. Sibly has recently been published: The History of the Albigensian Crusades (Boydell, Suffolk, 1999).

- La Croisade contre les Albigeois 1209-1249

- Pierre Belperron. Librairie Plon, Paris, 1942; and Librairie académique Perrin, 1967.

- Les Cathares

- Arno Borst. Payot, Paris, 1984.

- Le Catharisme: La Historie des Cathares

- Jean Duvernoy. Privat, Toulouse, 1979.

- Les grandes heures cathares

- Dominique Paladilhe. Librairie académique Perrin, 1969. An itinerary through the cathare country.

- The Inquisition : A Political and Military Study of its Establishment

- Hoffmann Nickerson. John Bale, London, 1923 and 1932.

- "Kill Them All... God Will Recognize His Own"

- Douglas Hill. Military History Quarterly, Winter 1997 (9:2) pp.98-108.

- The Yellow Cross, The Story of the Last Cathars 1290-1329

- René Weis. Penguin, London, and Alfred A.Knopf, NY, 2000. A reconstruction and account of the late phase of the Cathar movement. Author employed latest geographical maps, Vatican documents, and a personal visit to the sites to provide a vivid description of what happened to individuals as the Inquisition moved in on a small, remote, community of Cathars that survived in the Pyrenees.

Scene of actions in the Cathar Crusade

The Cathars: Who's Who In The Cathar War

The following are the

chief personalities during the Wars against the Cathars:

Crusaders and Crusade Leaders and Crusader Allies

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0902-Innocentiii.jpg

Pope Innocent III: Called the

crusade in 1208. Click here for more on Pope Innocent

III (http://www.cathar.info/120501_innocent.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0903-ArnaudAnaury.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0904-ArnaudDominic.jpg

Arnaud Amaury: Cistercian

Abbot of Cîteaux. Military commander of the crusade in

its early stages. Click here for more on Arnaud

Amaury (http://www.cathar.info/120502_arnaud.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0905-BernardOfClairvaux.jpg

Bernard of Clairvaux (Saint Bernard): Cistercian

Abbot who had tried to combat "heresy" in Toulouse and the

Languedoc by preaching against it in the century before the

Crusade. Click here for more on Bernard of

Clairvaux (http://www.cathar.info/120517_bernard.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0906-SimonIVDeMontfort.jpg

Simon de Montfort: Titular Earl of Leicester, and lord of

Montfort. Took over leadership of the Cathar Crusade

after the initial victories at Béziers

and Carcassonne.

Click here for more on Simon

de Montfort (http://www.cathar.info/120503_simon.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0907-AmauriDeMontfort.jpg

Amaury de Montfort: Earl of Leicester. Took over

leadership of the Cathar Crusade after the death of his father

Simon. Click here for more on Amaury de

Montfort (http://www.cathar.info/120503b_simon.htm)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0908-DominicGuzman1.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0909-DominicGuzman2.jpg

Dominic Guzmán (Saint Dominic): A preacher

who set up the religious order ("The Dominicans") which

established and ran the first

Papal Inquisition. Click here for more on Dominic Guzmán

(http://www.cathar.info/120504_guzman.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0910-BernardGui.jpg

Bernard Gui: A Dominican Inquisitor who left a

useful manual for identifying and punishing Cathars and other

supposed "heretics". Gui, by the way, is depicted

earlier in his life as the villain in Umberto Eco's The

Name of the Rose. Click here for more on Bernard Gui

(http://www.cathar.info/12050401_gui.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0911-KingLouisVIII.jpg

Louis VIII: King of France. Joined the Cathar Crusade

and later led it. Click here for more on Louis VIII

(http://www.cathar.info/120505_blanche.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0912-BlanchDeCastile.jpg

Blanche de Castile: (1188-1252).

Regent of France (1226-36) during the infancy of her son Louis

IX, King of France. Click here for more on Blanche de

Castile (http://www.cathar.info/120505_blanche.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0913-LouisIXBurns.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0914-LouisIX7thCrusade.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0915-LouisIX8thCrusade.jpg

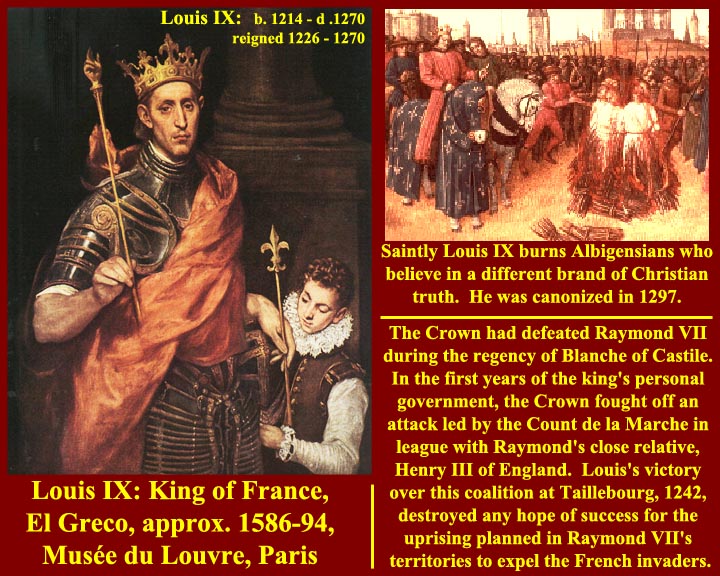

Louis IX: King of

France, also known as Saint Louis, a Crusader King. Click here

for more on Louis

IX (http://www.cathar.info/120505_blanche.htm).

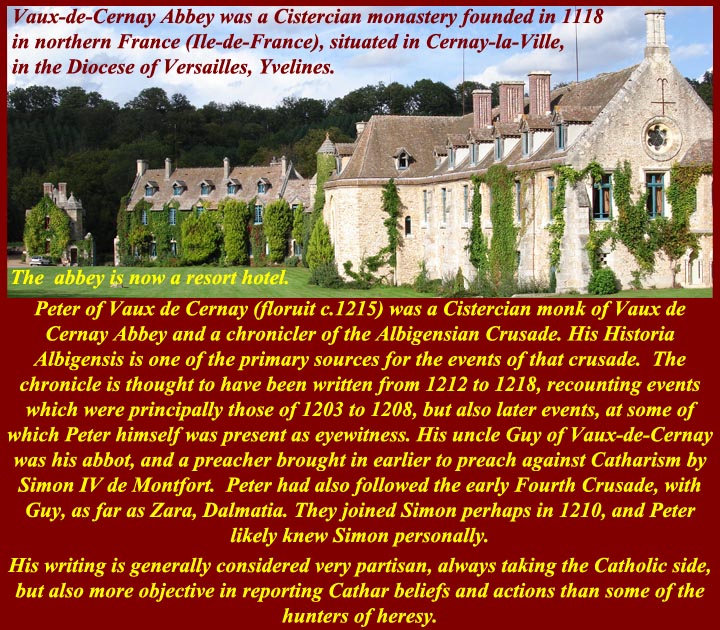

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0916a-AbbayeDesVauxDeCernay.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0916b-HistoriaAlbigensis.jpg

Guy and Pierre Des Vaux-de-Cernay. A Crusading Cistercian

Abbot (Guy) and his nephew (Peter), a monk who left an

invaluable record of the Crusaders actions and their beliefs.

Click on the following link for more on Pierre

Des Vaux-de-Cernay and his Historia Albigensis

(http://www.cathar.info/121205_historiaalbigensis.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0917-FulkOfMarsaile.jpg

Fulk (or Folquet) de Marseille: A troubadour who

later became Bishop of Toulouse. Click here for more on Fulk de

Marsielle

(http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0917-FulkOfMarsaile.jpg).

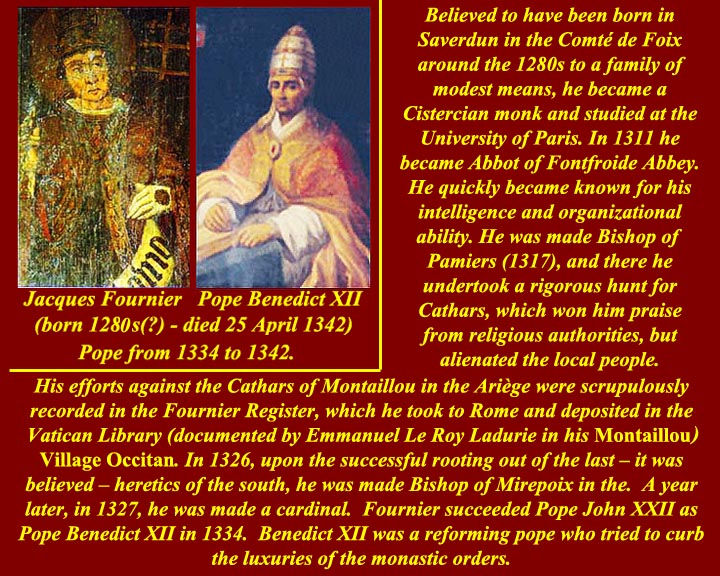

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0918-JacquesFournier-BenedictXII.jpg

Jacques Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers: (c 1280 - 1342) Famous

for his Inquisition records which survived in the Vatican

Archives after he was elected Pope as Benedict XII. Click here

for more on Jacques Fournier

(http://www.cathar.info/120520_fournier.htm).

Opponents and Victims of the Crusade, and their

Partisans

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0919-PereElCatolic.jpg

Peter II: (1174-1213)

King of Aragon (1196-1213). Close relative and ally of

the Counts of Toulouse. Recognised as the greatest

Crusader in Christendom at the time, but opposed to the

Crusade against his own vassals. Click here for more on Peter II

(http://www.cathar.info/120506_peter_ii.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0920-Raymond6Toulouse1.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0921-Raymond6Toulouse2.jpg

Raymond VI: (1156-1222), Count of

Toulouse (1196-1222). Click here for more on Raymond VI

(http://www.cathar.info/120511_raymond_vi.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0922-Raymond7Toulouse1.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0922-Raymond7Toulouse2.jpg

Raymond VII: (1197-1249), Count of Toulouse

(1222-1249). Click here for more on Raymond VII

(http://www.cathar.info/120512_raymond_vii.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0923-MontsegurFortress.jpg  http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0924-MontsegurFall.jpg The last Cathar castle to fall was the apparently impregnable Montsegur fortress. In 1242, it took 10,000 attacking troops ten months to capture the fortress that was defended by 100 Cathar fighters. Click here for more on Montsegur (http://www.catharcastles.info/montsegur.php?key=montsegur). |

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0925-RaymondRogeTrencaval.jpg

Raymond-Roger Trencavel: (1184-12093). Viscount of

Carcassonne. Relative of the Counts of Toulouse. Click

here for more on Raymond-Roger

Trencavel

(http://www.cathar.info/120513_trencavel.htm).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CRUS0926-RaymondTrencaval2.jpg

Raymond Trencavel II: (1204-126).

Viscount ofCarcassonne. Son of Raymond-Roger. Click here

for more on Raymond

Trencavel II

(http://www.cathar.info/120513b_trencavel.htm).

Raymond Roger: Count of Foix (1188-1223). Click here for

more on Raymond Roger

Roger Bernard II: Count of Foix

(1223-1241). Click here for more on Roger Bernard II

Roger IV: Count of

Foix (1241-1265). Click here for more on Roger IV

Savaric de Mauléon: (

Mauléoun). (1181-1233) Vassal of King John

of England and ally of the Counts of Toulouse.

Click here for more on Savaric de

Mauléon

Count of Comminges: Vassal and ally of the Counts of

Toulouse. Click here for more on Count of

Comminges

Viscount of Béarn: Vassal and ally of the Counts of

Toulouse. Click here for more on Viscount of

Béarn

Esclarmonde of Foix: Parfaite.

Click here for more on Esclarmonde

of Foix

Guilhem Belibaste: (c 1280 - 1323) The last known Cathar Parfait

in the Languedoc, burned at the stake in 1323. Click here for

more on Guilhem

Belibaste

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Click this lie to jump to images of Baltic crusaders and defenders]

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Crusades

The Baltic/Northern Crusade

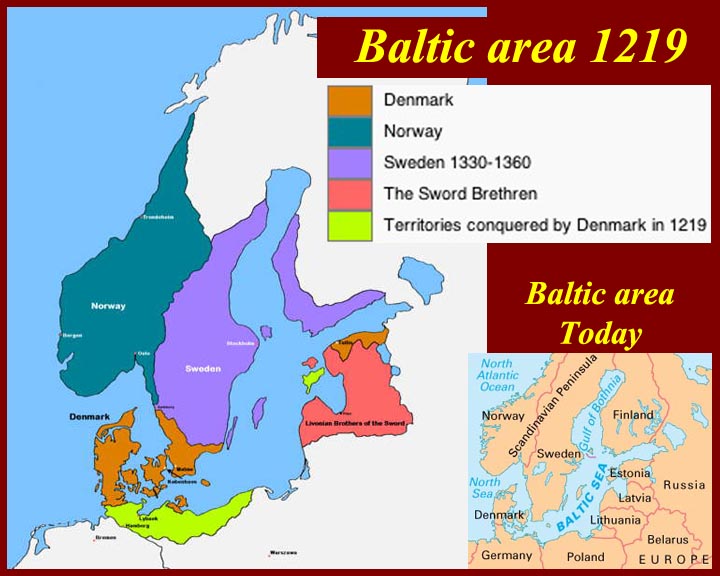

| Northern Crusades | |

| Date | 12th and 13th century |

| Location | Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Prussia |

| Belligerents | |

| Crusaders | Pagans |

| Commanders and leaders | |

| Valdemar I of Denmark Valdemar II of Denmark John I of Sweden Albert of Riga Anders Sunesen Caupo of Turaida † Theoderich von Treyden† Volquin† Wenno Wilken von Endorp† Tālivaldis of Tālava† |

Lembitu of

Lehola† Ako of Salaspils† Visvaldis of Jersika Viestards of Tērvete Nameisis of Zemgale† |

From: http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/crusades.htm

The Baltic Crusade

Ruth Williamson

SCAND 344, June

2002

Introduction - Expanding

Frontiers - Crusading Orders - Military Strategy and

Conquest

- The Struggle for Lithuania - Bibliography

Introduction

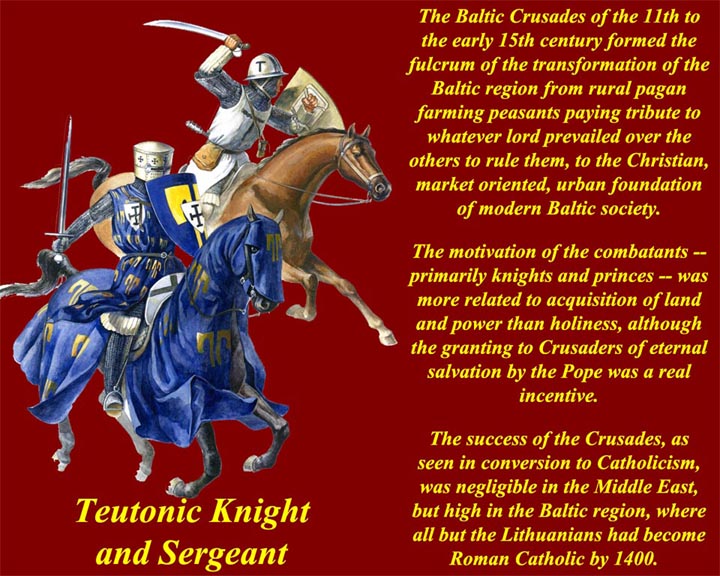

The Baltic Crusades of the 11th to the early 15th century formed the fulcrum

of the transformation of the Baltic region from rural pagan

farming peasants paying tribute to whatever lord prevailed

over the others to rule them, to the Christianized,

market-oriented, urban foundation of modern Baltic

society. The rise and fall of the knighthood during

this period is indicative of the changes that

occurred. The institution of knighthood represented

the values of medieval Europe, and the incursion of the

knightly orders into the Baltic countries during these

crusades transmitted those values to the Baltic regions

despite the strong resistance of the independent, unchurched

peoples living there. The involvement of north Germans

and Scandinavians in the crusades left critical political

and social imprints and changes that affected the future

path of historical events in the Baltic region that was to

evolve into the countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

The Baltic Crusades are a branch

of the Catholic crusading movement that comprised five main

Crusades that occurred between 1096 and 1221. The

Crusades were “armed pilgrimages” (Haverkamp, p. 12) called

and blessed by the Pope, originally to reclaim Jerusalem and

its surrounding territory in the Middle East, both

considered “holy land,” for the Catholic Church. The

enemies in these Crusades were supposed to be non-Christian,

primarily followers of Islam. As the balances of power

shifted in the 12th century, the Eastern Orthodox Church, based in

Constantinople and the seat of the Christian Byzantine

Empire, became a focus of the Crusades as well. As in

the Baltic Crusades, the motivation of the

combatants—primarily knights and princes—was more related to

acquisition of land and power than holiness, although the

granting to Crusaders of eternal salvation by the Pope was a

meaningful incentive. Notably, the success of the

Crusades, as measured by conversion to Catholicism, was

negligible in the Middle East, but high in the Baltic

region, where all but the Lithuanians were converted to

Catholicism by the close of the 13th century.

Expanding

European Frontiers

Turmoil prevailed among 12th century north central Europe’s (present-day

Germany) secular and religious political powers, with

players such as the Holy Roman Emperor, the Pope, assorted

princes and nobles, and bishops vying for territory, power

and revenues. Peasants were struggling to escape the control

of these same players, so incentives were offered to

peasants to settle lands to the east for the benefit of a

particular player’s interests, and the incentive usually

included relief from the obligations of serfdom. To

make up the lost revenues, cities and commercial enterprises

were taxed instead. This structure was not the norm in

medieval Europe, which was dominated by the feudal system

that gave the balance of power to landed nobles under their

demesne powers.

East of north central Europe is,

of course, the Baltic region. The traditional peasant,

farming and raiding lifestyle of Baltic peoples was ended

when central European societies’ need for more land grew

into a need for the products and natural resources available

in the Baltic, attracting professional traders who then

wanted some kind of protection from the security risks to

life and property of trading in the remote northeastern

territory. At the same time, the Catholic Church was

interested in preventing the Russian Orthodox Church from

making inroads any further west into the Baltic lands, and

in converting all Orthodox Christians to the one and true

Catholic Church and re-uniting all of Christendom.

Thus the 12th century saw a convergence of the goals of the

Catholic Church and the secular commercial interests to

expand the frontiers of medieval European civilization into

the Baltic lands for political and economic reasons.

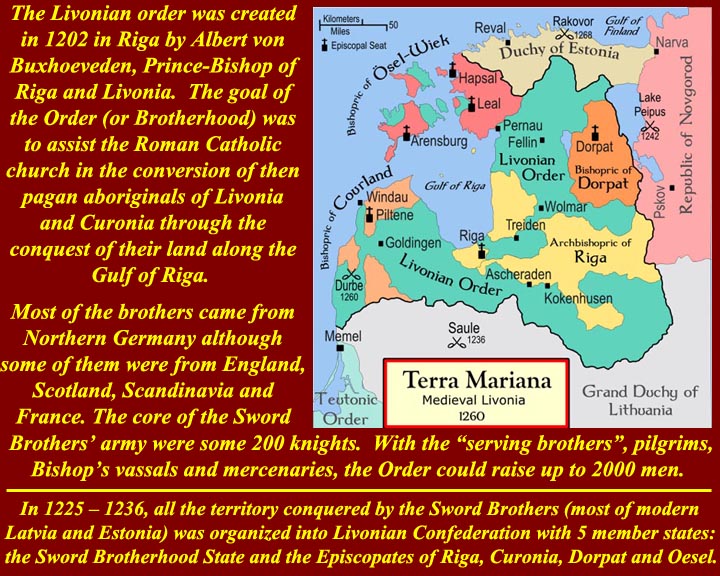

Meinhard, an Augustinian monk

from Holstein, accompanied some merchants up the Dauvaga

River in the late 12th century on a mission to begin the attempt to

convert the people of Livoniato Christianity, establishing

the first church building and the first churched community

of believers. Building on Meinhard’s foundation, his

successor Bishop Berthold established a crusading force to

more aggressively convert the local populace in 1198.

This effort coincided with the declaration of the Fourth

Crusade by Pope Innocent III and is considered the beginning

of the Baltic Crusade. The next bishop, Albert,

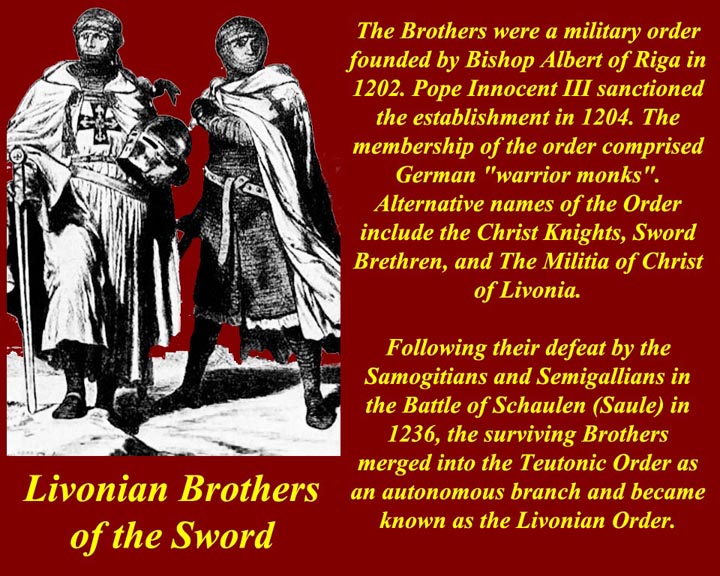

established the knightly crusading order known as the

Swordbrothers in 1202, obtained papal blessing of an

official crusade in 1204, and by 1208 had forcibly converted

the Kur and Lett peoples to Christianity.

Concurrently, after Bishop Albert established the city of

Riga in 1201 its growth was fed by the economic activity

generated by the Crusades and Riga attracted merchants

looking for a stable base from which to trade in the Baltic

region. Albert was a strong leader who managed to

placate the competing interests of the Pope and the Holy

Roman Emperor and to fend off a Danish take-over move before

his death in 1229.

The

Crusading Orders

The Christian military orders

emerged around 1120, after the First Crusade to the Holy

Land, evolving from the early form of charitable religious

orders doing good in the Holy Land to become a blend of

military and religious disciplines embodied in a special

type of knight, a religious knight. Pope Urban II, in

calling the First Crusade, established a new Christian

philosophy, saying that it was possible to combine warfare

and religious life for “…to lay down one’s life for one’s

brothers is a sign of love.” (Forey, p.12). Suceeding

popes relied on this new philosophy to recruit both

short-term crusading forces from the upper classes as well

as the permanent members of the various Christian military

orders. The first orders were called The Templars and

The Hospitallers, for reasons related to their original

functions. The Teutonic Order grew out of a German

order that ran a hospital in Acre, near Jerusalem, in 1193,

and became established in central Europe by invitation of

the Hungarian king in 1211. In contrast, the Order of

the Swordbrothers was specifically founded to provide a

permanent military presence in the Baltics to reinforce the

“missionary work” of converting of the population by force

without the necessity of relying on volunteer recruits.

While the missionary monks and

bishops introduced Catholicism into the Baltics, it was the

ascendency of the knightly crusading orders, first the

Swordbrothers and then the Livonian Order of the Teutonic

Knights, that defined the Baltic Crusades.

As with the other orders, the

Swordbrothers were an order of professional military men who

also took vows of devotion to Christ to live a monastic life

and fight against the unbelievers. Their ranks were

recruited for the most part from the non-landed,

administrative class of the lower nobility who also composed

the ministerial staff of medieval German princes. The

Order itself was broken into classes of knight, priests and

several classes of servants who performed a wide range of

essential duties. The Swordbrothers were led by their

master, who was elected from the ranks and held the position

for life. While Bishop Albert and the other

missionaries in the Baltic benefited from the presence of

the Order in its formative years, because the Swordbrothers

owed allegiance solely to the Pope in Rome, as the

Swordbrothers gained power and influence, they increasingly

encountered conflict with Bishop Albert.

Military

Strategy and Gradual Conquest

As the Swordbrothers gained

experience in warfare against the Baltic natives they also

learned how to effectively fight in the foreign climate of

Livonia by taking advantage of the ease of travel over ice

and snow in the winter, instead of struggling in the mud the

rest of the year. In addition, they learned to take

advantage of the tribal social structure of the Baltic

native populations, with many small groups intent on

fighting each other for local power. Using this

cultural characteristic the Crusaders conquered one small

tribal group at a time and recruited them to mount attacks

on the next tribe, whom they likely hated. So

gradually the Livs, Semigallians, and Selonians joined the

Letts and the Kurs in succumbing to Catholicism. The

Swordbrothers were also struggling for control of the land

and power that they increasingly thought befit their role in

the Christianizing and civilizing of Livonia. Bishop

Albert was forced to share 1/3 of his small holdings with

the Swordbrothers, and they held out for the right to claim

1/3 of all future lands gained through the crusading

effort. Meanwhile, the Bishop had to constantly

negotiate and hold off masked threats from neighboring

powers such as Russia and Denmark to gain a foothold in his

territory. The Swordbrothers were itching to take on

the Estonians who were fighting to claim the allegiance of

the defeated Letts, and had some successes in smaller

engagements when the Bishop wasn’t available to restrain

them. Ultimately in 1218, through the combination of

Russian aggression, the Swordbrothers’ ascendancy, and

Danish interest in gaining a foothold in Estonia and

fulfilling their Christian crusading vows by joining the

Baltic Crusade, the Baltic Crusade entered Estonia and

brought the Estonian people into the Catholic sphere.

The Chronicle of Henry

of Livonia is a primary source from this period, written

by a priest named Henry who lived in the region from 1205 to

1259 and recorded its history in 1225-6 for his

superiors. His account begins, “Divine Providence, by

the fire of His love….aroused in our modern times the

idolatrous Livonians from the sleep of idolatry and of sin

in the following way.” (Brundage, p. 25).

Henry’s biases reflect the prevailing Catholic view of the

time that the indigenous pagan people were deceitful and

untrustworthy because they were inclined to go through

cycles of adopting and then renouncing Christian beliefs,

according to the dictates of political expediency.

“The most treacherous man…was baptized, as were all the

others….They promised that they would always keep the

Christian law faithfully. This promise, however, they

later violated with their treacherous devices.”

(Brundage, p. 140). For instance, if they were about

to be killed they agreed to be baptized, but once peace

returned they washed their baptism off again in the river.

In the ten years after 1217

Estonia changed hands several times, ending up in 1227 back

under the Swordbrothers’ and Bishop Albert’s

regime. In 1234, veterans of the Jerusalem

crusades were invited to stop the invasion of pagan Prussia

into Christian territories and the Order of the Teutonic

Knights arrived in the Baltic -- a larger, more

traditionally established German-based order than the

Swordbrothers. After the complete defeat of the

Swordbrothers by the Lithuanians at the Battle of Saule in

1236, the remaining Swordbrothers merged into the Order of

the Teutonic Knights, forming the Livonian Order. In

1242 the Russians defeated the Livonian Order in the Battle

of Lake Peipsi, establishing a defined boundary between the

German-speaking Baltic lands and Russia that lasted for

centuries.

The

Struggle for Lithuania

In 1252 the Teutonic Order

captured the Lithuanian city of Klaipeda, cutting off

Lithuania’s only access to the sea (not regained by

Lithuania until the 20th century). In 1253

Duke Mindaugas of Lithuania -- surrounded by knights on

almost every side -- agreed to accept Christianity.

Then all of Lithuania fell into the Christian realm except

Samogitia which refused to recognize Mindaugas as their

leader and continued to fight the Order. When

Mindaugas was assassinated in 1263 by an insider, Lithuanian

reverted to pagan faith and a chaotic time followed .

In 1284 the Teutonic Order succeeded in defeating Prussia,

which disappeared as a distinct tribe, assimilating into the

neighboring societies of Poland, Germany and

Lithuania. Later German conquerors appropriated the

name ‘Prussia’ for themselves.

The Crusaders in the 14th century continued the consolidation of their

hold on the Baltic lands, strengthening their power in

Estonia in 1343 as a result of the peasant rebellion against

Danish rule and the subsequent Danish sale of northern

Estonia to the Teutonic Order for 10,000 marks. Early

in the century Grand Duke Gediminas of Lithuania had

successfully expanded his territory to the south and east

and also prevented Crusaders’ incursion into the land.

But in 1382 Lithuania lost Samogitia and it was ruled by the

Teutonic Knights for almost 30 years. In 1386 Grand

Duke Jogaila of Lithuania preserved his country by marrying

the Polish queen in the Union of Kreva and created the

powerful Lithuanian/Polish state. In this union is

cemented the Christian character of Lithuania.

Finally, in 1410, Lithuania, in a coalition with Russians,

Poles, Tatars and Czechs, defeated the Teutonic Knights in

the Battle of Zalgiris at Tannenberg and Grunwald, ending

the military existence of the Teutonic Knights forever.

Sources

· City Paper. “The Baltic Crusades: A

Chronology,” n.d,. http://www.balticsww.com/Crusaders.htm

(9 April 2002)

· This site is sponsored by a Baltic regional

newspaper called City Paper and is a graphically attractive

timeline of the Baltic Crusades combined with a narrative of

excerpts from The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia and William

Urban’s book The Baltic Crusade. [Apparently

now a dead link -- TKW]

· Brundage, James A. The Chronicle of Henry

of Livonia; A Translation with Introduction and

Notes. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press,

1961.

This is the

current classic translation of this important primary source

of the early period of the Baltic Crusades into English.

· Christiansen, Eric. The Northern Crusades:

The Baltic and the Catholic Frontier, 1100-1525. Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 198

As its title

indicates, this book covers over three hundred years of

crusades in the Baltic region of northeastern Europe.

A detailed but concise chronology of the events of the era

is included, as well as a list of the relevant northern

secular and religious rulers of the Baltic, Scandinavia and

Russia. It has a number of excellent, detailed but

easy-to-read maps of the region at various milestone dates

in the period covered. The content appears to

thoroughly cover the secular, political, social and

religious factors issues in northeastern Europe during the

existence of the crusades in the Baltic region.

· Forey, Alan. The Military Orders: From

the Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Centuries. London: MacMillan

Education Ltd., 1992

The title says

it all—this book is an exhaustive study of the military