http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0301EarlyMedSetttlements.jpg

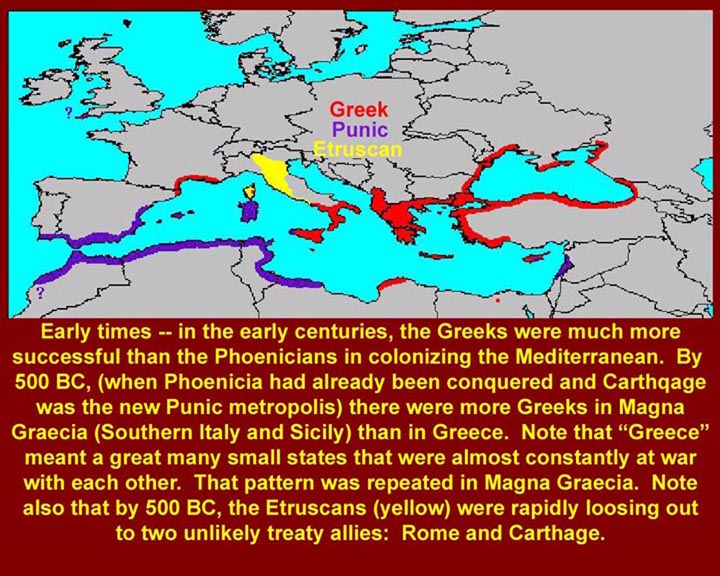

Greek and Punic positions in the Mediterranean -- getting ready to fight.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0302GreekBireme1989.jpg

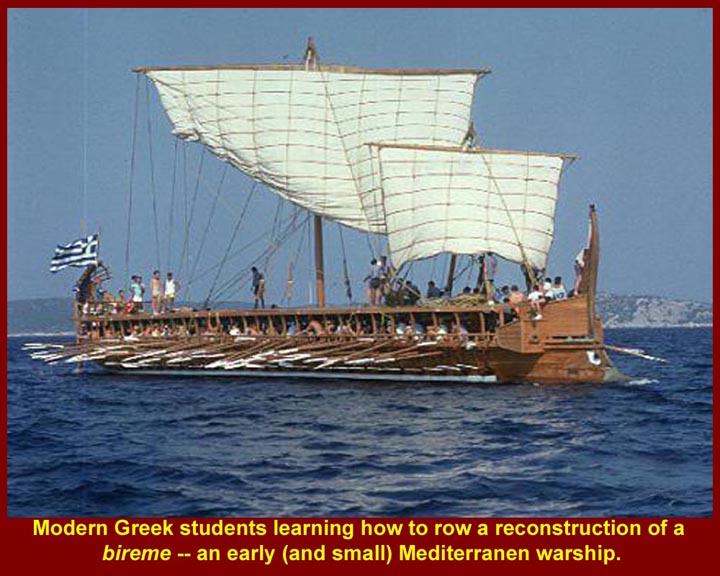

Basic early Greek warship reconstructed and crewed by Greek students.

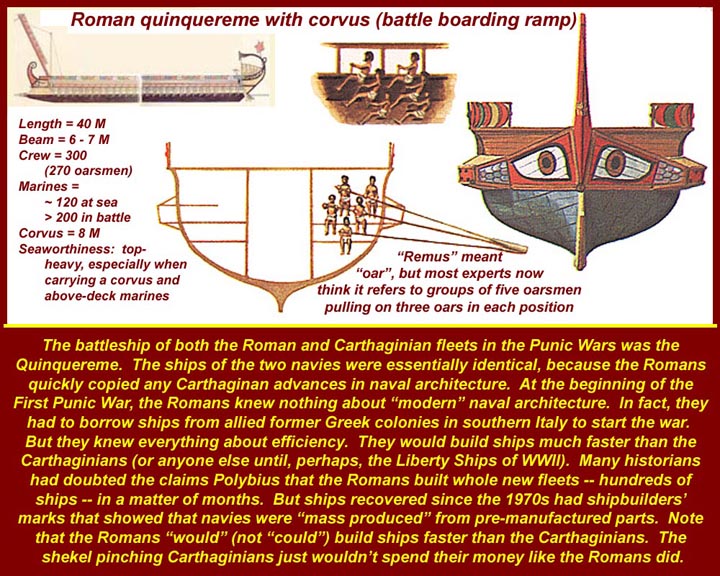

In the Punic Wars the main battle vessels of both the Roman and Carthaginian navies were quinqueremes ("five oars' or "five oarsmen"). Roman quinqueremes carried a total crew of 420, 300 of whom were rowers, and the rest marines. Leaving aside a deck crew of c. 20 men, and accepting the 2𣇻 pattern of oarsmen, the quinquereme would have 90 oars in each side, and 30-strong files of oarsmen. The fully decked quinquereme could also carry a marine detachment of 70 to 120, giving a total complement of about 400. A "five" would be c. 45 m long, displace around 100 tonnes, be some 5 m wide at water level, and have its deck standing c. 3 m above the sea.

When the Roman Republic, which untill then had lacked a significant navy, became embroiled in the First Punic War with Carthage, the Roman Senate set out to construct a fleet of 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes. According to Polybius, the Romans seized a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme and used it as a blueprint for their own ships, but it is stated that the Roman copies were heavier than the Carthaginian vessels, which were better built.

The most important facts about the Roman navy were that the Roman Republic always had the resources (money and timber and shipbuilders and oarsmen/crewmen) to make and man as many ships as were needed and that they were always ready and willing to expend those resources. The Carthaginian navy was always up against materiel and manpower limits and wasn't always able to get appropriations from the money-men back home.

The Carthaginian reluctance to loosen military purse-strings also limited the effectiveness of Carthaginian land forces in the First and Second Punic Wars.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0303RomePosition650BC.jpg

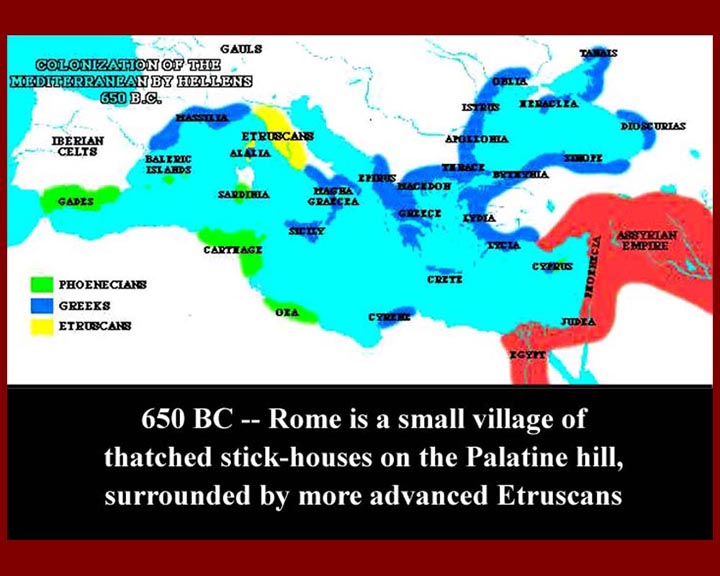

The domain of infant Rome: thatched huts on the Palatine hill and surrounded by Etruscans. This is the time of the Roman "Monarchy" (actually a gang of outlaws with a "king" who was a gang leader.) The last four kings (of the total seven) were Etruscans, it it was they who brought Rome into the "modern" world.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0304HerodotusWorldMap.jpg

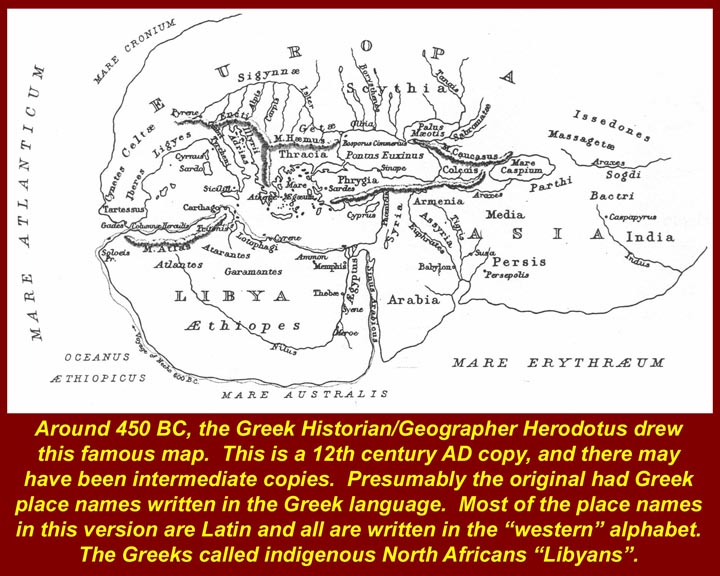

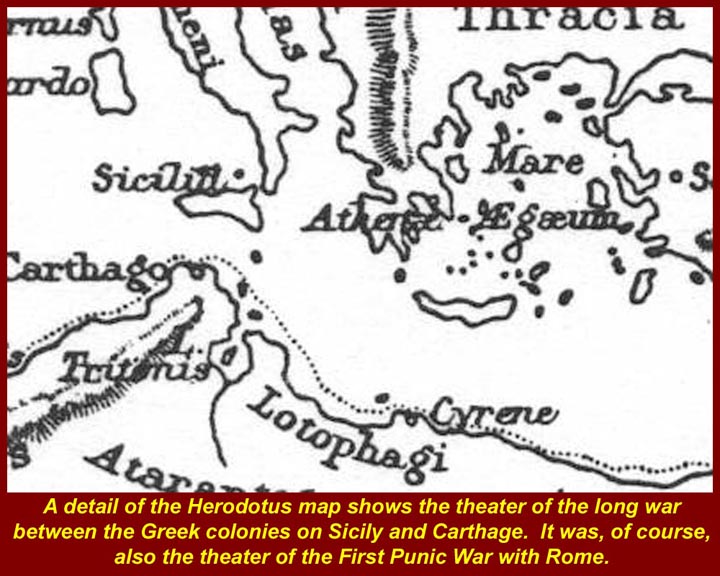

Map said to have been made by Herodotus around 450 BC. (Really a 12th century copy with lord knows how many intermediate copies, mis-copies, additions and subtractions.)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0305HerodotusMapDetail.jpg

A detail of the Herodotus map. By the time Herodotus made his map, Rome and Carthage had been in a treaty relationship for 50 years. In Early days, the treaty just said that Rome had a right to trade in Carthage and the western Mediterranean islands and to hold territory on the Italian mainland. Later revisions of the treaty put more restrictions on Roman trade, but still allowed trade at Carthage. Clearly, the Carthaginians were the major power dealing with an upstart. The treaty relationship lasted about 250 years -- until Rome broke it with an unprovoked attack on Messana, Sicily in 264 BC.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0306CarthageRomePositionsBC380.jpg

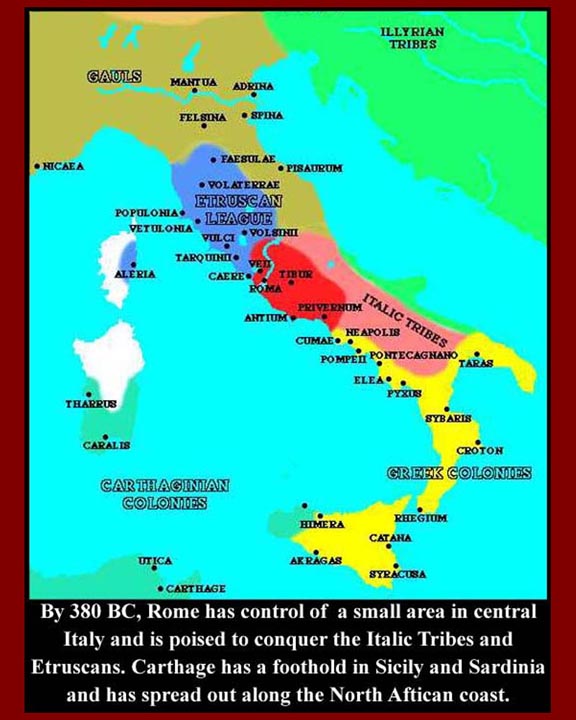

By 380 BC, Rome had a small part of central Italy. Carthage had spread out on the North African coast and had a foothold on Sicily and had control of the southern half of Sardinia.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0307RomeCarthage270BC.jpg

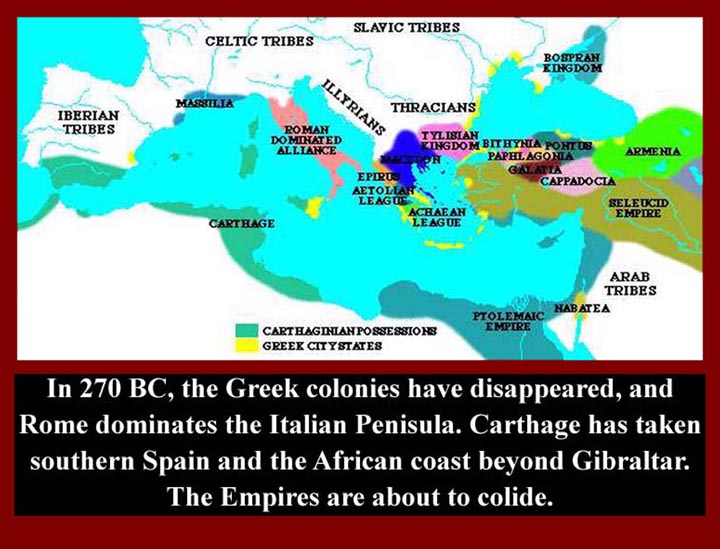

Things had changed dramatically by 270 BC. Carthage had Sardinia and Corsica and the Western half of Sicily -- and looking greedily at the eastern half where feuding Greek city-states had hired Campanian mercenaries to fight amongst themselves. Rome, meanwhile, had taken over all of the Italian Peninsula south of the Rubicon (it didn't take Cis-Alpine Gaul in the North until Julius Caesar conquered it. All those Campanian mercenaries in the Greek side of Sicily were now Roman or at least from Roman territory.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0308SyracuseApolloTemple.jpg

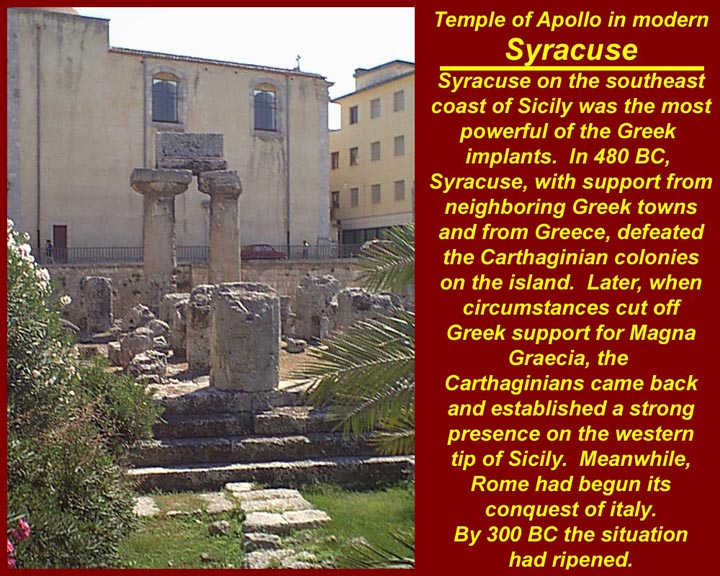

The Greek city states in eastern Sicily were all that separated the expanding militaristic Roman republic (they had thrown out the last Etruscan king years before) from the Carthaginians. This is the Greek Temple of Apollo in downtown Siracusa, Sicily (ancient Syracuse)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0309CarthageAgEconomy.jpg

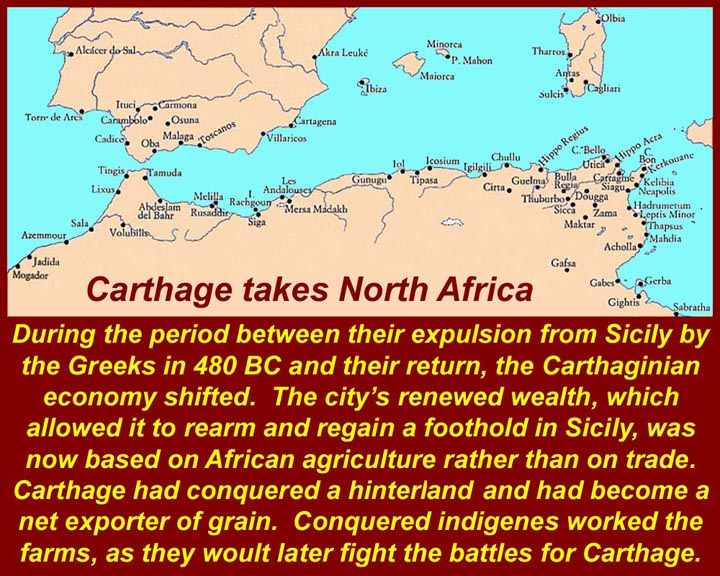

Carthage had developed a solid agricultural economy and combined wealth from its traditional Mediterranean trade with new money from agricultural exports. A "war party" in the popular assembly and among the leadership thought that some of that money should be invested in expansion of Carthaginian territory in Sicily.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0310GreekCarthSettlements.jpg

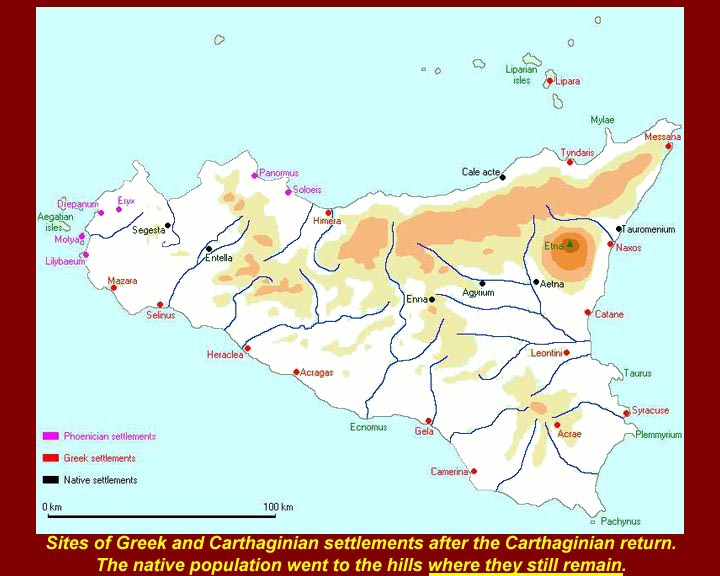

Greek and Carthaginian towns had always been mostly on the coast of Sicily. The indigenes had gone to the hills (where they remain to this day.) Support from Greece for the Greek colonies on the island had withered away -- the cities that had sent out colonists were too embroiled in their own local wars to continue to support their colonists. The Greek towns in Sicily also wasted their resources fighting among themselves. Syracuse, in particular, was a local power with ambitions.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0311GreekTempleSicilyAgrigento.jpg

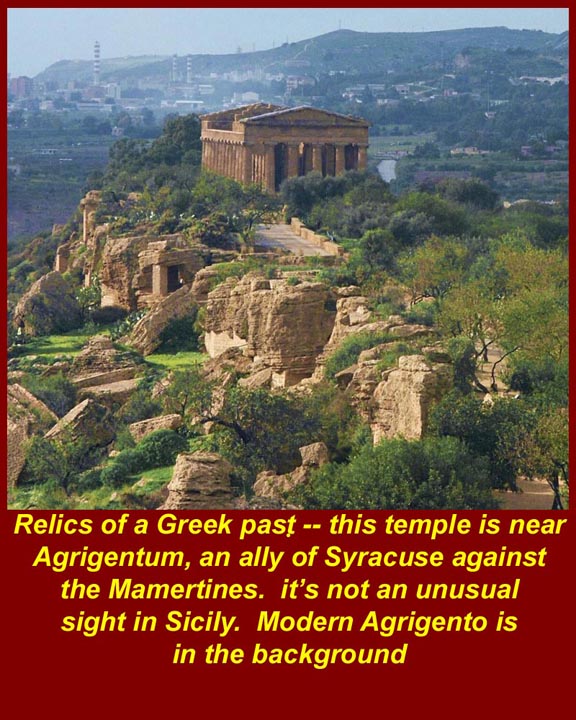

Acragas (later Agrigentum) was a Greek town in the middle of Sicily's southern coast. Syracuse (in the center of the eastern coast) in alliance with Acragas hoped to take over all the Greek towns of southeast Sicily.

At the same time, King Pyrrhos from Epiros (back in Greece) tried to make inroads in both southern Italy and in Sicily. He was king of the Greek tribe of Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house (from ca. 297 BC), and later he became King of Epirus (306-302, 297-272 BC) and Macedon (288-284, 273-272 BC). He was one of the strongest opponents of early Rome. He won some battles, but they were the proverbial "Pyrrhic victories" -- he used up his resources and went back home. The image is of a Greek temple near modern Agrigento.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0312MessanaMamertines.jpg

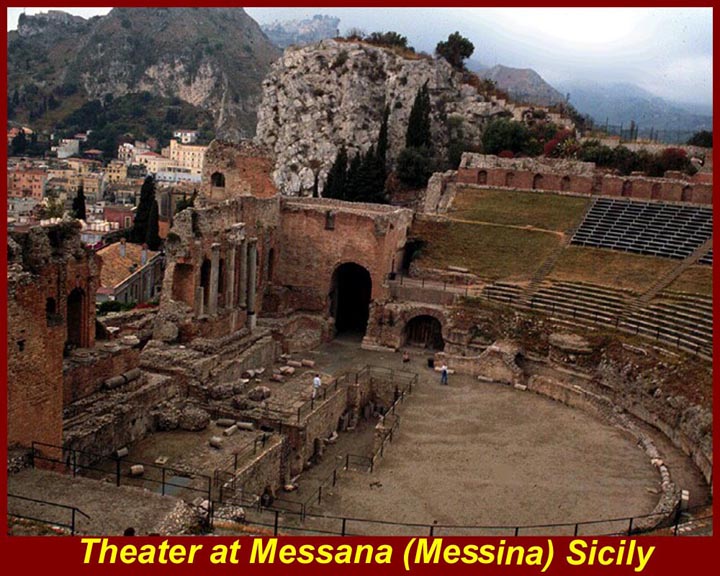

The excuse for war. Campanian mercenaries, who called themselves Mamertines (i.e., servants of the Oscan Mars), had taken over Messana (now Messina) after being discharged when Agathocles of Syracuse died in 289 BC. They used Messana as a base for raiding other towns and for piracy at sea, and they had an informal alliance with Carthage. King Pyrrhus had defeated the Mamertines outside their town in 278 (at the request of Syracuse) but instead of taking Messana and eliminating the Mamertine thorn in the side of Syracuse, Pyrrhus attacked Lilybaeum, a town on the far western tip of Sicily which belonged to Carthage. Eventually Pyrrhus left the area leaving the Mamertines to resume their raiding and piracy.

In 275 BC, a separate group of Campanians, who were mostly deserters from the Roman army, took Rhegium (now Reggio di Calabria) on the Italian mainland, opposite Messana. A Roman legion took back Rhegium and stayed in the area -- about two miles from Messana.

In 265, Hiero II of Syracuse tried to rid eastern Sicily of the Mamertine bandits. The Mamertines asked both Carthage and Rome for help against Hiero. Carthage reacted first to aid their informal allies -- and also to expand into eastern Sicily and to keep Hiero from becoming too powerful. They sent a military force to Messana. The Mamertines quickly realized they had made a mistake -- the Carthaginians had chased off Hiero, but they they wouldn't go back home. After some fast negotiations with Rome, a deal was made, and a Roman force arrived under the command of Apius Claudius Caudex (the last part of whose name meant either "tree-trunk" or "Blockhead") to save the "Roman" Mamertines from the Carthaginian menace. This broke and ended permanently the 250 year old alliance between Rome and Carthage. (If this sounds similar to the beginning of the Mexican War after the founding of the Republic of Texas, it's because it is similar.)

Carthage then rapidly formed an (un-natural) alliance with Hiero, and, as they say, the rest is history.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0313MessinaStrait.jpg

The Roman force that crossed the narrow straits into Sicily easily took the port of Messana. But the Carthaginians under one of their many commanders named Hanno and the Syracusans besieged the town. Apius Claudius sent them an ultimatum: stop the siege or go to war. The Carthaginians wouldn't lift the siege, so Apius declared war. The First Punic War would last 23 years.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0314MessanaTheater.jpg

Another Greek remnant. A theater, still in use, in Taormarina near Messina. Roman theaters were free-standing and Greek theaters were built into hillsides. This one has a a "Romanized" stage area.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0315FirstPunicWarBattles.jpg

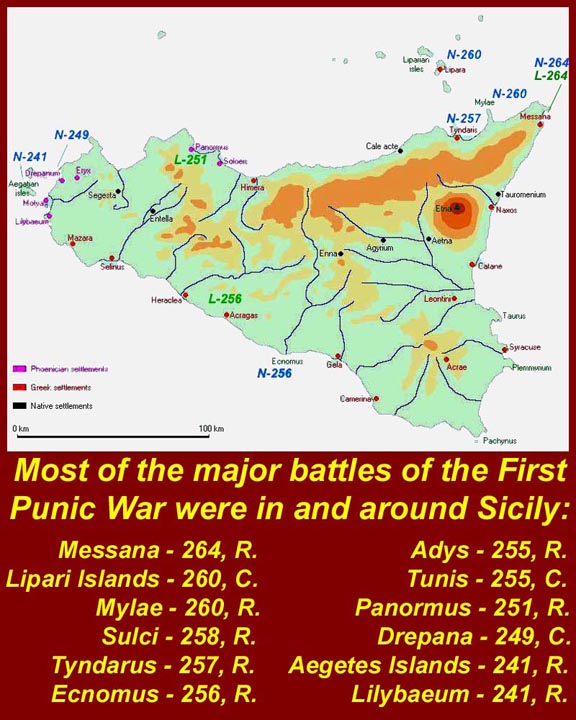

The First Punic War was all about Sicily. Neither side really needed any resources from Sicily, but each side feared the strategic advantage the other side would have by controlling the island. Most of the major battles of this first war were fought on or around the island, and (as was also the case in the Second War) Rome was willing and able to commit more resources to the effort. Rome was always able to come up with more men and, most importantly, more ships after inexperienced Roman naval commanders lost fleet after fleet -- mostly to storms and faulty navigation. By the last years of the First Punic War, Carthage was leaving Hamilcar Barca un-reinforced on the Island. Toward the end of the 23 year war, Carthage just failed to keep up the pace that Rome set. Although history has concentrated on the Second Punic War, this first war war the one that made the difference and that made the Second War impossible for the Carthaginian side to win.

[Why does the Second Punic War win out in historical coverage and continuing public interest? Two reasons: first, there were great leaders on both sides, Hannibal and Scipio Africanus, with the latter pulling out a victory after long years of Carthaginian dominance. Second, Polybius, the first and greatest historian of the Punic Wars, was actually present for the Second Punic War but was writing from other sources about the first. In his multi-volume History, he writes one book about the first war and three about the second. We simply know have more information about the personalities and the battles of the second war.]

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0316Quinquereme.jpg

When the First Punic War started, the Carthaginians had quinqueremes and the Romans had smaller ships. By good fortune (according to legend) the Romans acquired a wrecked Carthaginian quinquereme and quickly reverse-engineered it. Roman shipyards, almost certainly manned by experienced shipwrights from the former Magna Graecia started churning out quinqueremes at a much faster rate than the Carthaginians could match.

Despite heavy losses to storms and mischance -- several hundred ships, more than were lost in all the battles against the carthaginians -- the Romans always were able to float replacements, and sometimes in very short periods of time. Modern historians long doubted that Roman shipyards could really build 200 ships over a two month period, but builders marks on timbers of ancient ships recovered in the 1970s showed that it was common to build fleets of standardized prefabricated parts -- "weapons of mass production". In addition, the Romans probably built ships in ports of former Magna Graecia towns all along the southern coasts of Italy.

Finally, there was the vast Roman supply of good shipbuilding wood, which the Carthaginians couldn't match. Their best supply was actually in Sardinia, and the relatively small Roman naval victory at Sulci Island off the southwest Sardinian coast cut Carthaginian supply from Sardinia early in the war (258 BC). By the end of the War, Rome had more and bigger ships. The theory that Carthage went back to smaller models because they were more maneuverable doesn't hold up. They just didn't have the wood and wouldn't/couldn't spend the money to import it.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0317Corvus.jpg

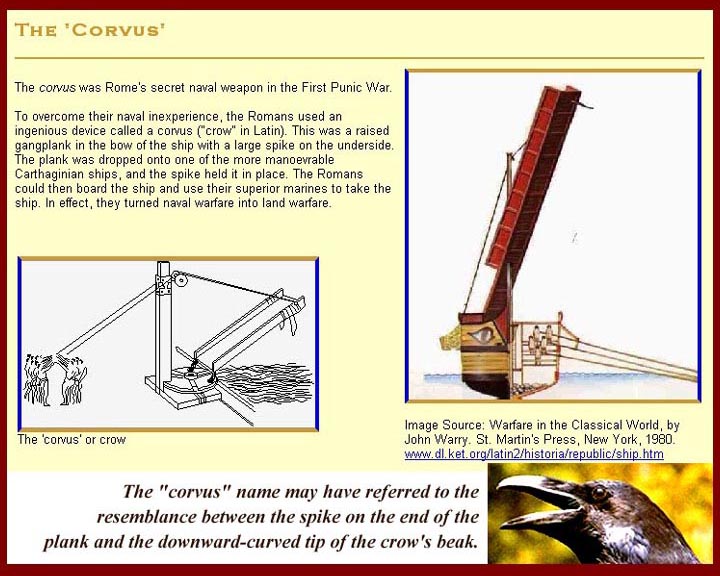

The corvus, Rome's "secret weapon" was no real secret -- just a new idea. It's hard to keep secret an 8 to 10 meter ramp with a huge spike on the end, especially when it has just crashed down on the deck of your ship and there are hundreds of Roman marine infantry pouring over it. After... no, during the battle of the Lipari Islands, the first naval battle of the war (260 BC), the Romans realized that they were no match for Punic naval skills (yet). At the second battle (Mylae, same year), they deployed the Corvus and won decisively, capturing 30 Carthaginian ships. And the operative word is "capture" -- those ships were soon back in other battles on the Roman side. The Carthaginians did learn one lesson: station have infantry on any ship that might encounter Romans. This somewhat limited Roman success in later battles, but the Romans, from here on, had the advantage at sea -- if they had a competent admiral, which was not always the case.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0318CorvusToCatapult.jpg

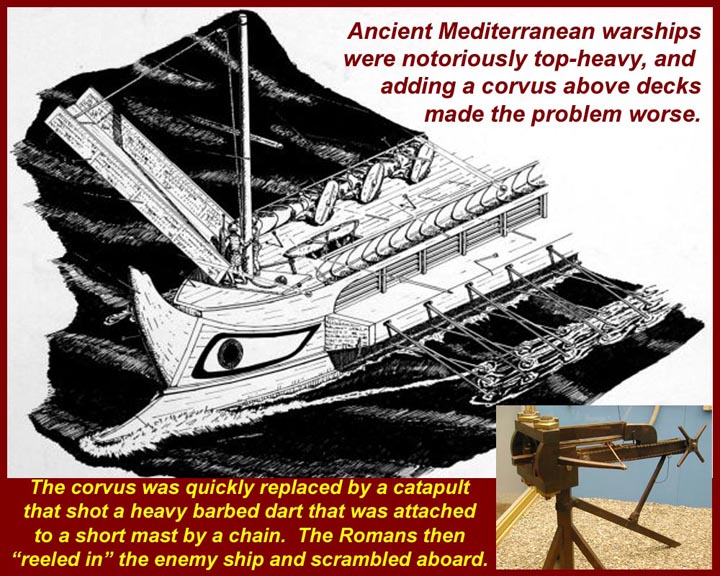

The Romans also had to learn a lesson about the corvus. It made already top-heavy ships even more unstable. Veering (coming about with the wind astern) could be harrowing, and moving through a storm without capsizing could be well nigh impossible. As usual, Roman engineers had an answer. The fleet abandoned the corvus and mounted instead large catapults, which shot heavy barbed darts into enemy ships. A chain that flew out behind the dart was attached to a shorter mast (forward, where the corvus mast had stood), and the enemy could be reeled in for boarding by those same marines. The object of the Roman game was always to turn a sea battle into an infantry charge. The Romans kept their advantage but no longer destabilized their ships.

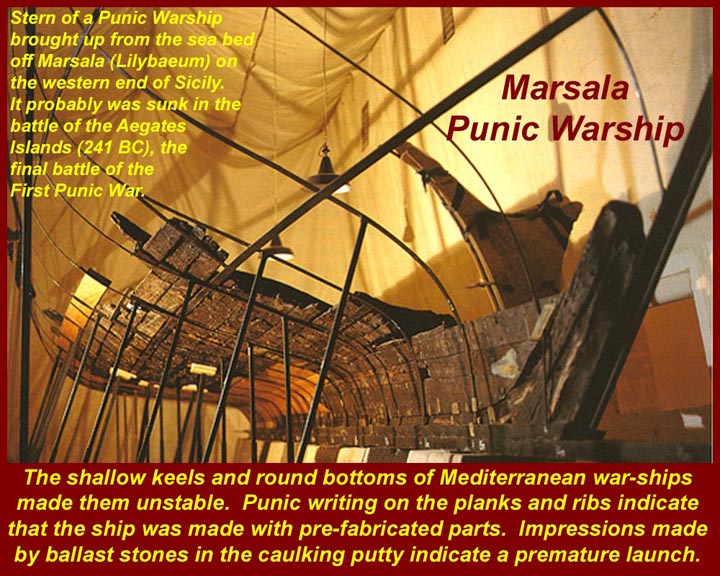

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0319MarsalaPunicWarship.jpg

The stern of a Punic warship was protected for more than two millennia by the mud off the shore of Lilybaeum (modern Marsala) on the western end of Sicily). The ship is thought to be a casualty of the Battle of Lilybaeum, the last naval battle of the war. Only a small part of the wreck was recovered, the rest having been destroyed long ago by wave and tide, but the part that was brought up showed two things: the Carthaginians, by this time, were also using prefabricated parts (Punic inscriptions were found giving instructions -- "tab A in slot B" -- and Punic ships were being launched prematurely, i.e., before the caulking putty had time to set.

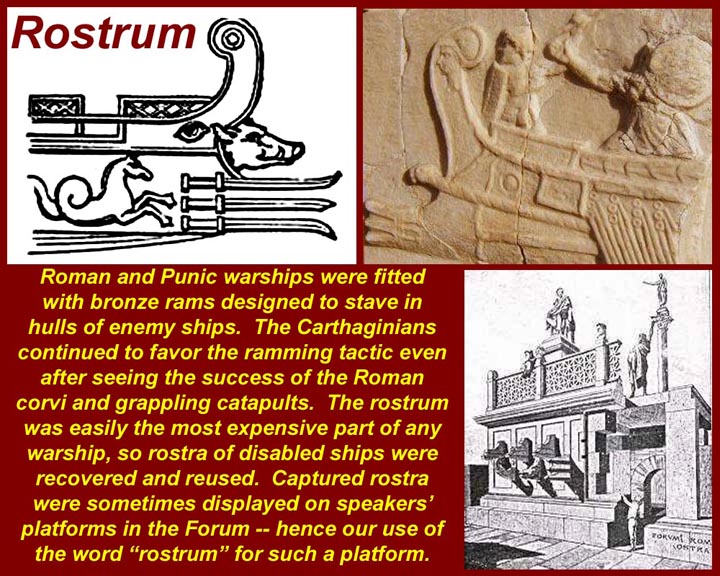

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0320Rostra.jpg

The rostrum (plural = rostra), the bronze ram at the front of Mediterranean warships, was the most expensive part of the vessel. Captured rostra were war booty and were reused or put on display, mounted on the front of speakers' platforms. During the Punic wars, bronze was still a metal of coinage in Rome.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0321NavalSiege.jpg

If you needed to attack a fortified port, you might build or buy one of these. Rome routinely contracted shipbuilding out to former Magna Graecia shipyards. As Rome took over territories in the Italian Peninsula, she inherited both their shipbuilding facilities and their owners, who were integrated into the Roman plutocracy. War was big business.

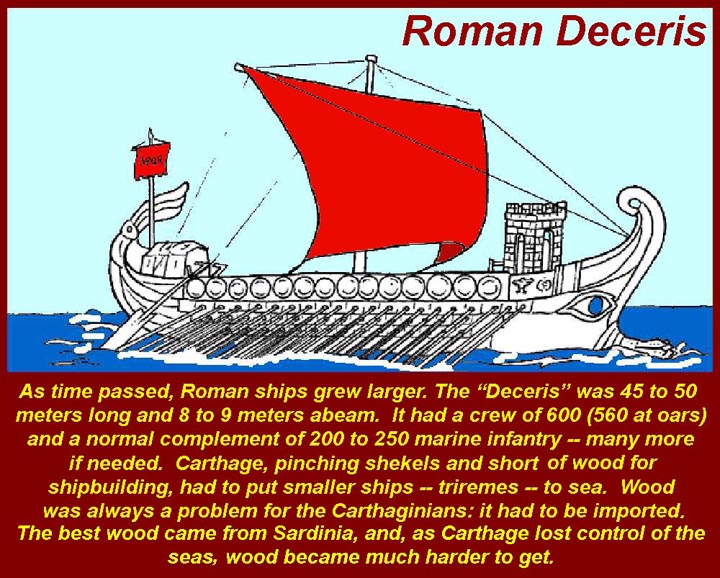

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0322Deceris.jpg

Mediterranean warships just kept growing. The Roman deceris was like a quinquereme on steroids. Height at the gunwale was a major consideration -- it was important to have a height advantage when approaching your enemies so that you could shoot down at them while your marines were preparing to swarm onto their decks. But these ships had no deep keel, and the more you had above the waterline the more weight in ballast you needed to keep your ship upright. Ship size increased over the centuries, and Ptolemy of Egypt eventually had a (rather impractical) "forty" -- forty rowers per position. It's thought that it was twin-hulled (like the siege tower above ) with two banks of oars and ten rowers per oar. Even after classical times, rowing was, with sail, a standard means of moving cargo and of fighting in the Mediterranean. Renaissance galleys fought their last great sea battle at Lepanto in 1571. (See http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi303.htm for more info.) Galley builders found that the greatest practical number of rowers per oar was eight.

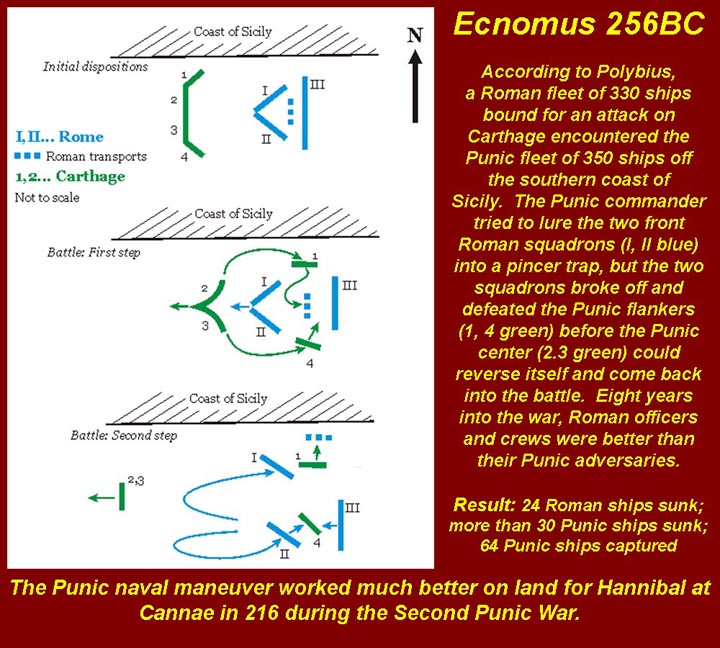

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0323CapeEcnomus.jpg

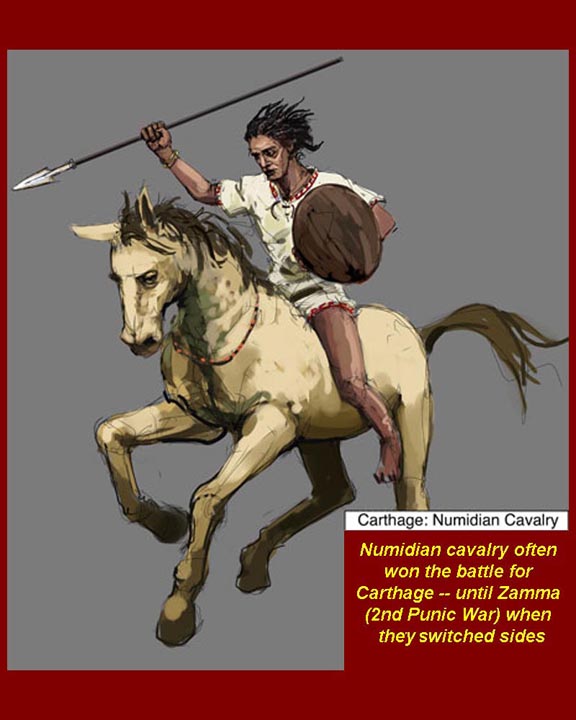

In the naval Battle of Cape Ecnomus, off the southern coast of Sicily, the Carthaginians tried to draw off the two leading Roman squadrons. The plan was that the Carthaginian flanks would the attack the third Roman squadron which was towing transports. The Carthaginians hadn't reckoned with the Roman capability of pursuit. When the Carthaginian center fell back, the Romans did surge forward, but it quickly overtook and heavily damaged the retreating Carthaginian center. The two leading Roman squadrons then quickly came about and trapped the Carthaginian flankers. The Carthaginian strategy was essentially the same as the strategy used later on land by Hannibal in the Second Punic War, but Hannibal had the hugely dominant Numidian cavalry on his flanks, and they were not about to be trapped even if the Roman infantry had been able to turn about to engage the Carthaginian flanks. As we will see, at the Zamma battle that ended the Second Punic War, Massanissa's Numidians defected to the Romans, and that was the end of Hannibal's army.

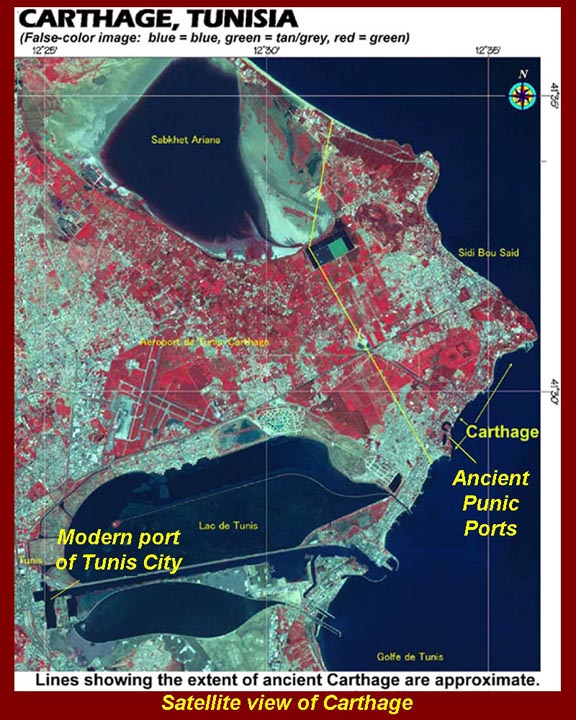

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0324CarthageSatelilte.jpg

Our now familiar satellite view of Carthage showing the location of the Carthaginian ports. The outer rectangular port was commercial. The inner circular naval port was also the headquarters of the Carthaginian admiralty.

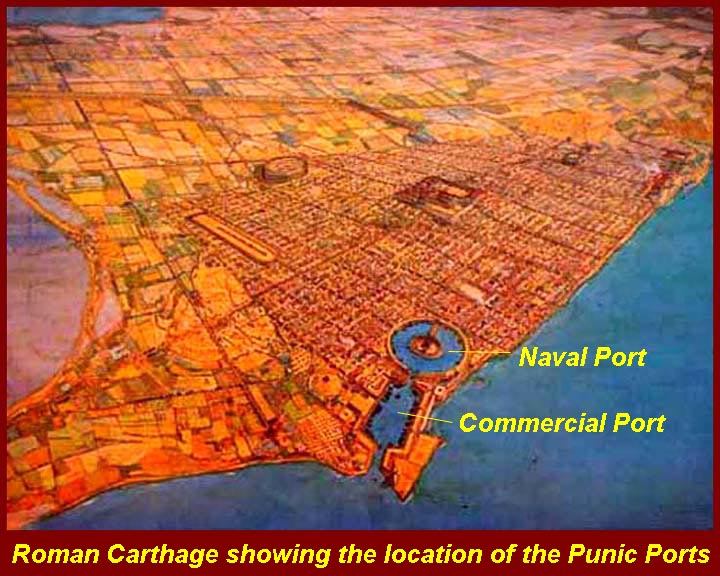

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0325PortsRomanCarthage.jpg

Carthage in Roman times. The image shows the location of the Carthaginian ports.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0326NavalPortSize.jpg

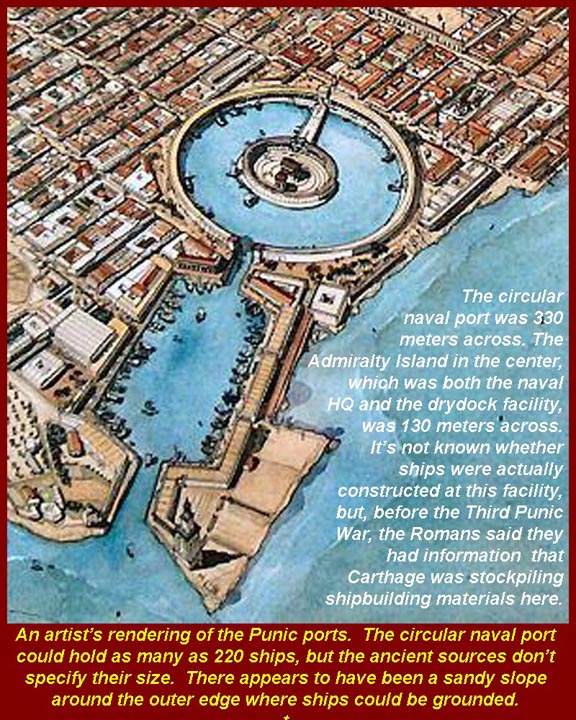

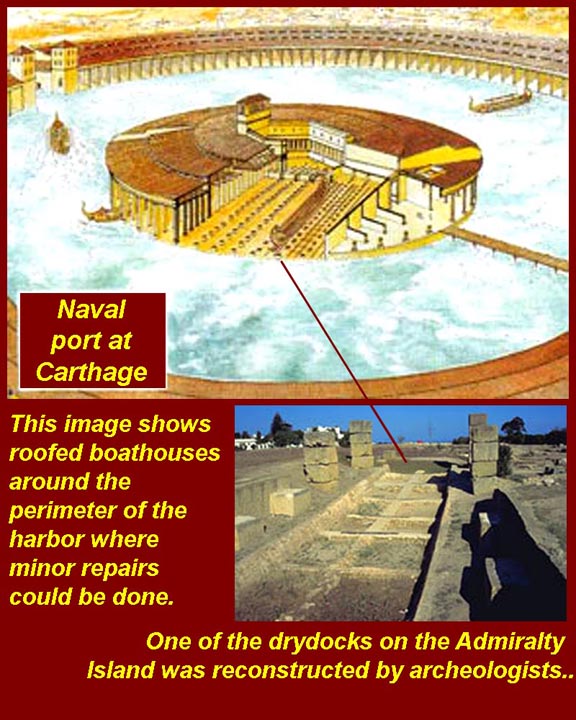

The naval port was 330 meters in diameter and could hold about 220 ships, each in its own shed. The sheds appear to have had sand bottoms and the ships were winched up onto the sand.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0327PunicAdmiraltyRecons.jpg

Artist's reconstruction of the naval port showing a cut-away view of the admiralty island. Archeologists have partially reconstructed one of the drydocks on the island.

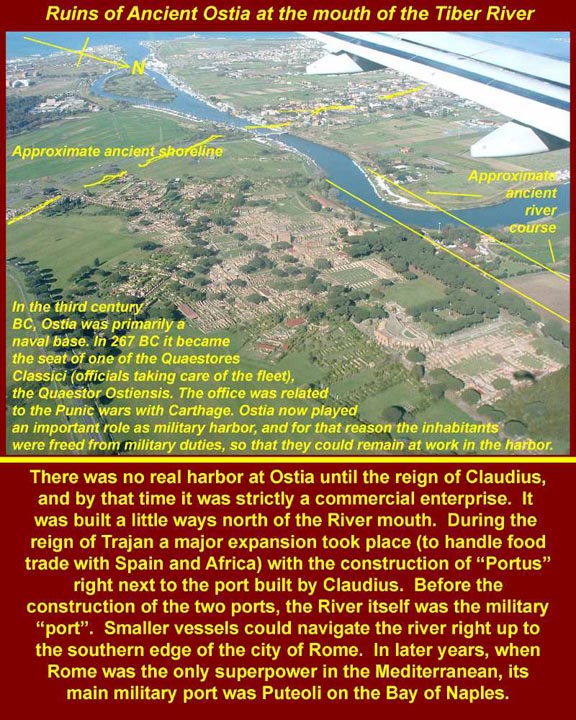

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0328OstiaAerial.jpg

Ostia was founded during the Roman monarchy period, long before the Punic Wars. The town guarded the mouth of the Tiber River, and the River itself was Rome's naval "port". Smaller vessels could navigate the river up to the southern edge of Rome (i.e., outside the Servian walls, but inside the present Aurelian walls). Ostia is not explicitly mentioned in the history of the First Punic War (southern naval facilities were probably used), but it is mentioned in accounts of the second Punic War.

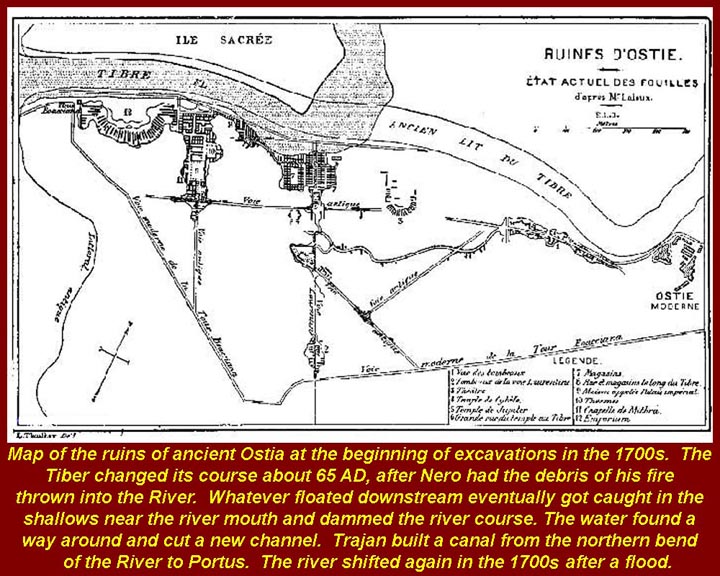

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAF0329CartinaOstia1700s.jpg

A map of the ruins of Ostia at the beginning of excavations in the 1700s.

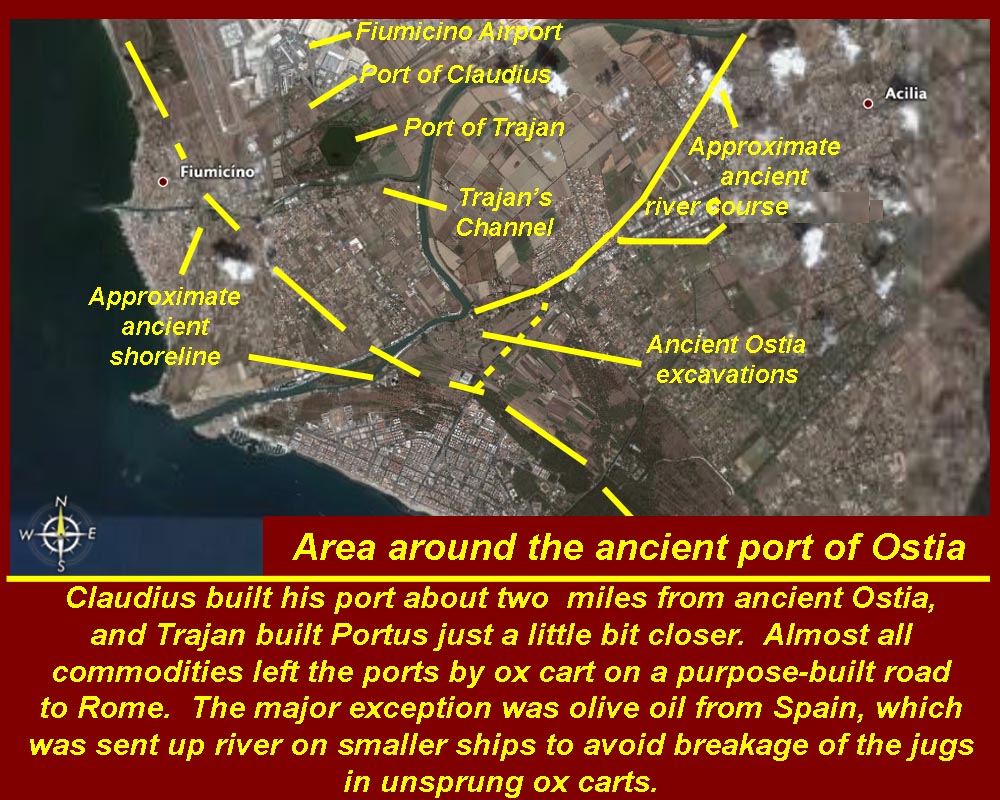

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0330OstiaEnvironsSatellite.jpg

A labeled satellite view of Ostia.

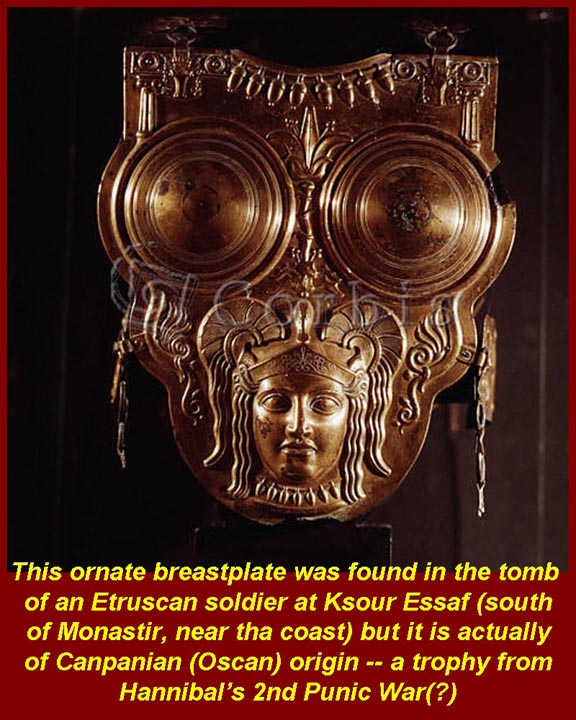

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0331TrophyBreastplate.jpg

A breast plate, now on display in the Bardo Museum in Tunis, is sometimes misidentified as Carthaginian. It was found in the tomb of a Carthaginian warrior, but it probably was captured as a trophy -- stripped from the body of a vanquished Campanian mercenary.

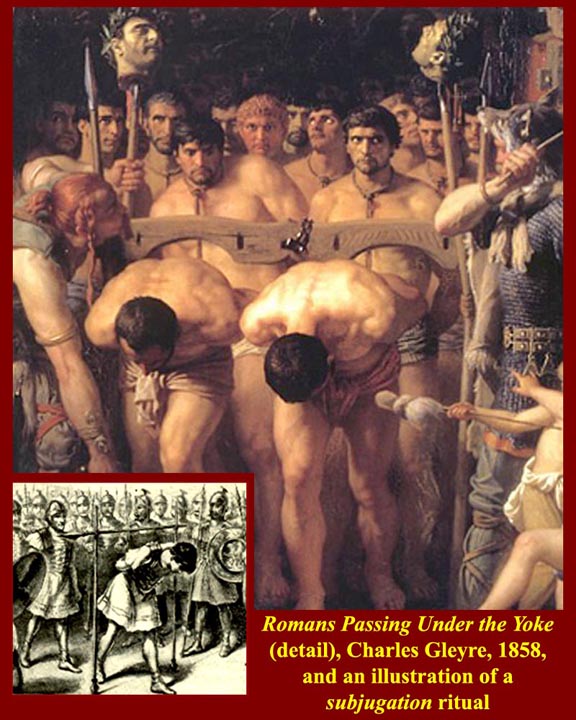

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0331bSubjugati.jpg

"Subjugation" was a ritual passing of prisoners under a real or symbolic yoke. From Latin sub = under + jugatus = yoke. The painting, a detail of which is shown, memorializes the defeat of one of Caesar's Roman armies by a Gallic force. It has become a fixture of the Swiss national mythology even though the actual defeat took place in what is now France. The insert shows a textbook illustration of a symbolic "yoke" of spears, under which barbarians are forced to walk by victorious Roman troops (time and place indeterminate).

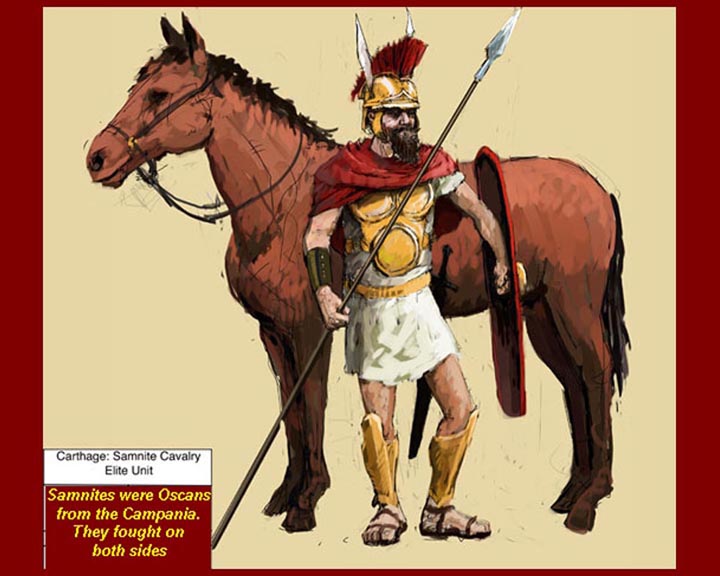

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0332SamniteCavalry3.jpg

Samnites were from the mountainous area northeast of the Campanian (around the Bay of Naples. Like the Campanians, they spoke an "Oscan" language (as opposed to Latin or Etruscan) and it's not at all certain that they were ethnically different from the Campanians -- the divisions of Italic peoples are based on perhaps fallacious distinctions that date back to the Romans who seemed to have felt a need to categorize folks. Canpanians and Samnites generally fought on the Roman side of the Punic Wars. Notice this cavalryman's breastplate.

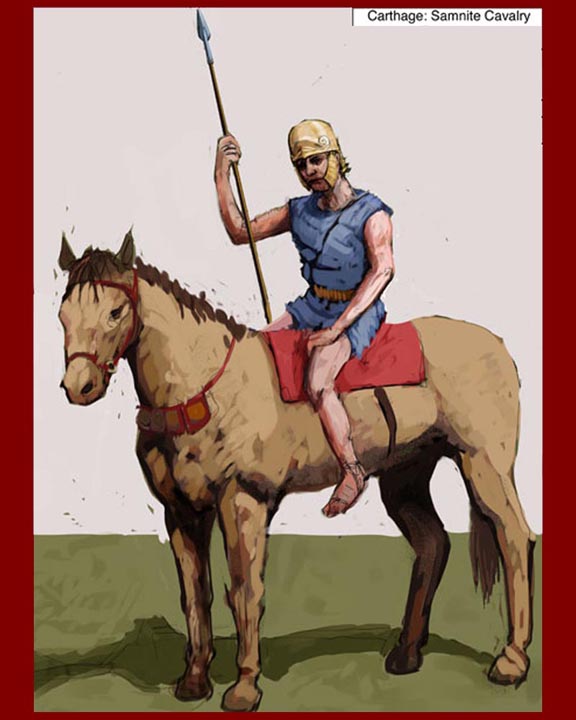

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0333SamniteCavalry2.jpg

Another Samnite, dressed differently. Auxiliaries didn't wear uniforms -- in fact, at this period, the Roman army regulars were also pretty much un-uniform.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0334SamniteCavalry.jpg

A third Samnite.

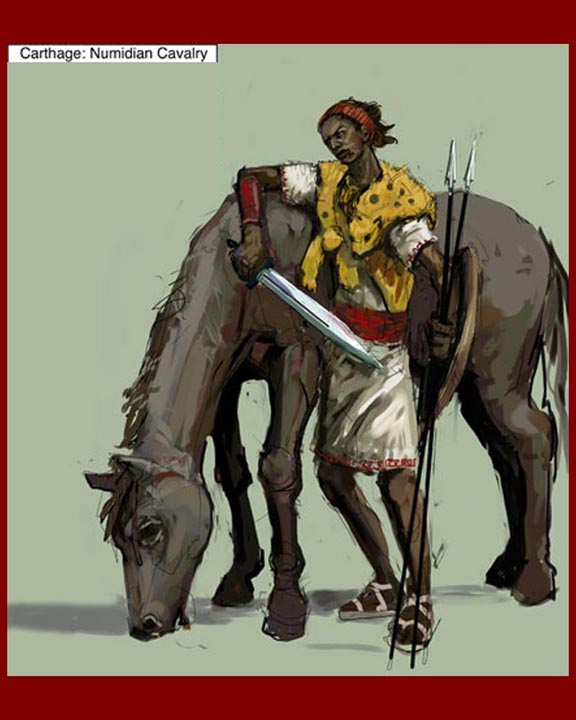

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0335NumidianCavalry3.jpg

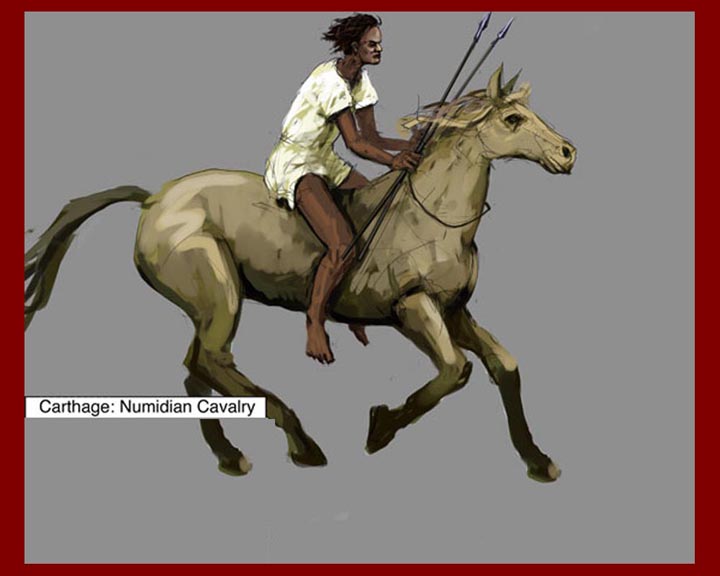

The key to Carthaginian victory on land, when it occurred, was the fierce Numidian mercenary cavalry. Their main weapon was a throwing spear, and each always carried several into their attack.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0336NumidianCavalry1.jpg

Numidian cavalryman.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0337NumidianCavalry2.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0338MauritanianArcher2.jpg

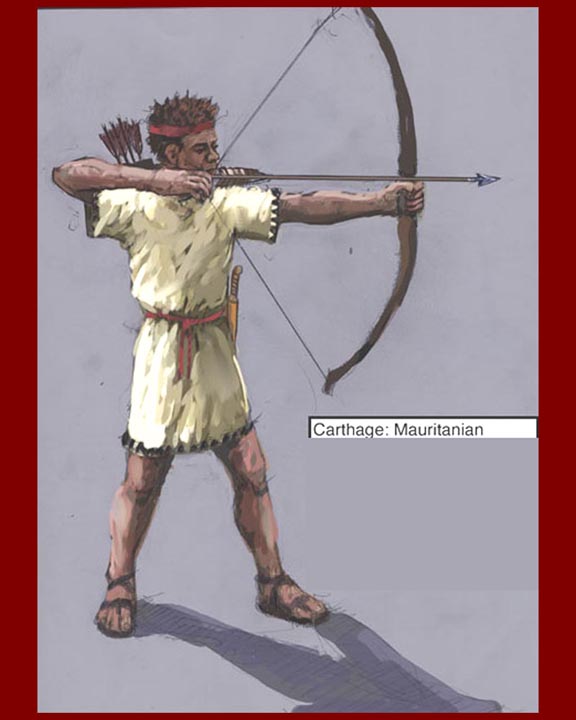

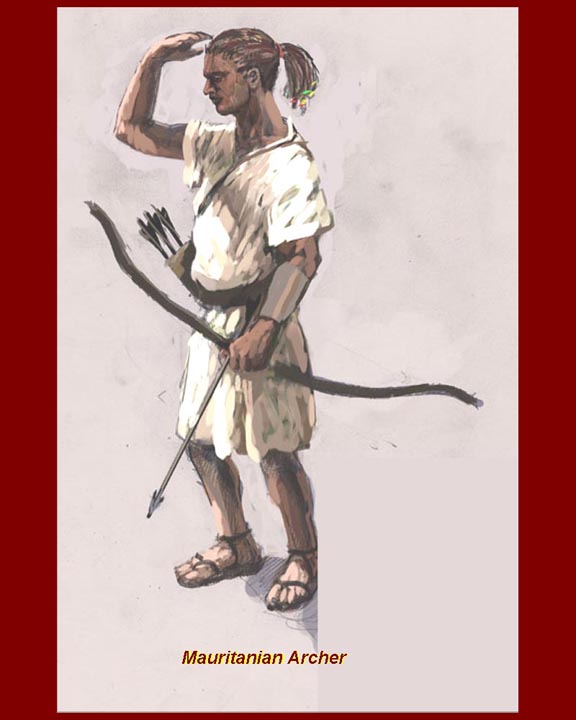

Mauritanian archers fought on the side of the Carthaginians.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0339MauritanianArcher1.jpg

Mauritanian archer.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0340Maharbal.jpg

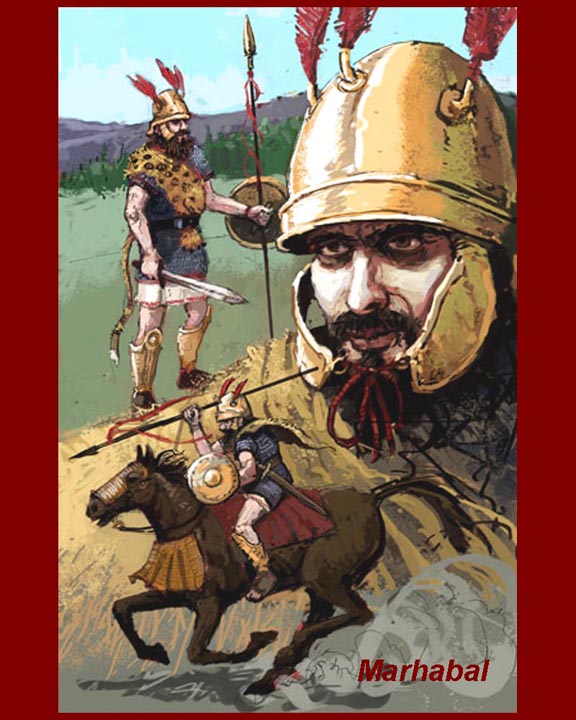

Artists impression of Maharbal, who was Hannibal's cavalry commander during the Second Punic War, gives us a view of what Carthaginian officers wore. His name indicates that he was Carthaginian, but he probably commanded mercenary cavalry. Although the officer corps of the Carthaginian army was actually composed of Carthaginians, all the troops were usually foreign Mercenaries.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0341CarthaginianArray.jpg

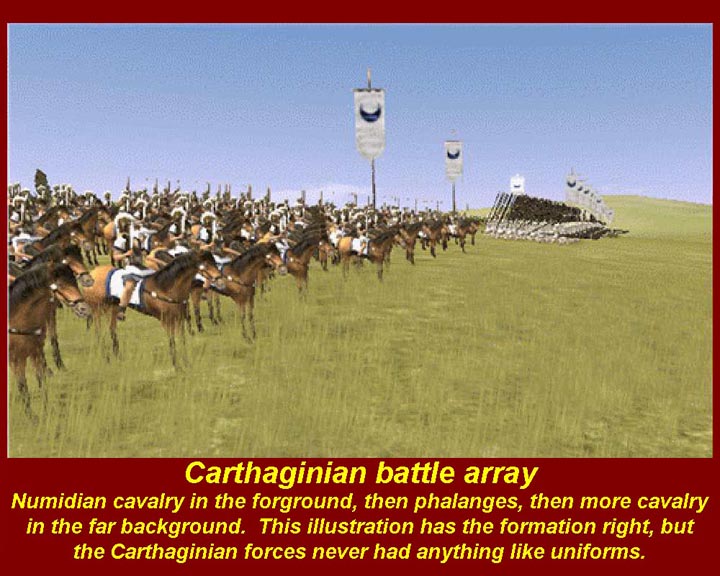

Forward edge of the Carthaginian army. Cavalry, foreground, then phalanges (singular = phalanx) of infantry, then, of in the distance, more cavalry. The image is somewhat defective because it shows a uniformity of costume that was never present in the Carthaginian armies.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0342IberianScutari.jpg

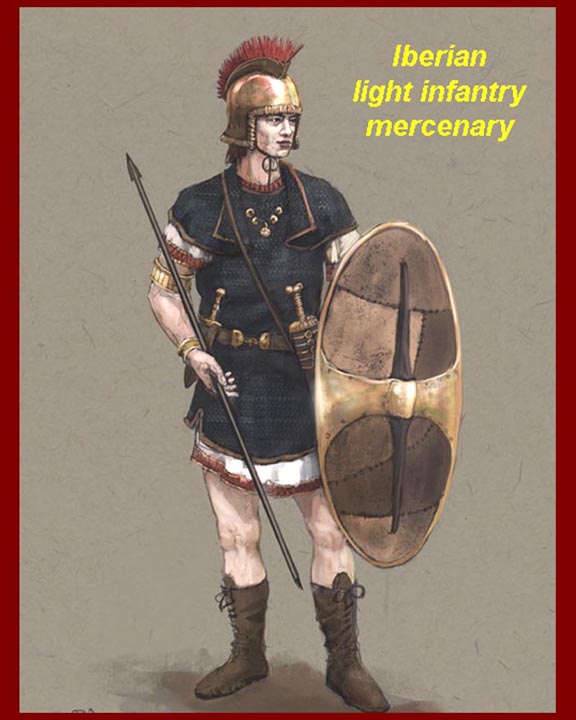

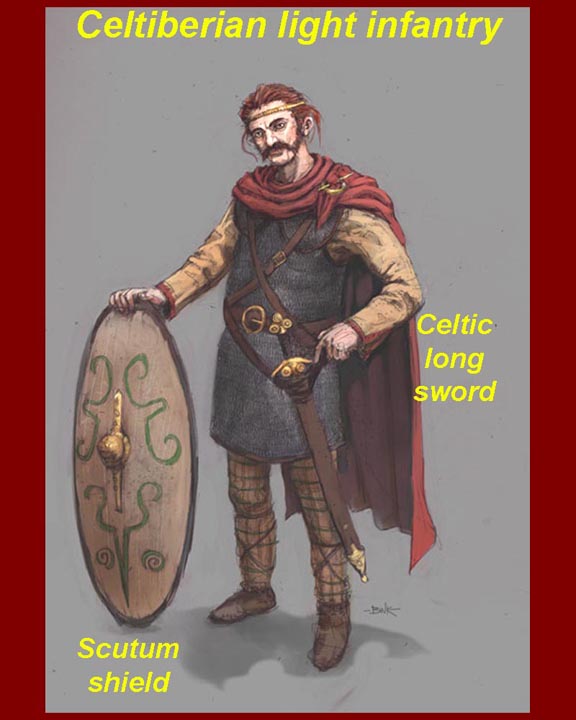

Iberian Scutari were light infantry (phalanx infantrymen were the heavies) and were so called because of the kind of large oval shields they used. Carthaginian army.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0343IberianMercenary.jpg

Celtiberian mercenaries -- more Carthaginian light infantry.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0344IberianInfantry1.jpg

Iberian mercenary. Carthaginian army.

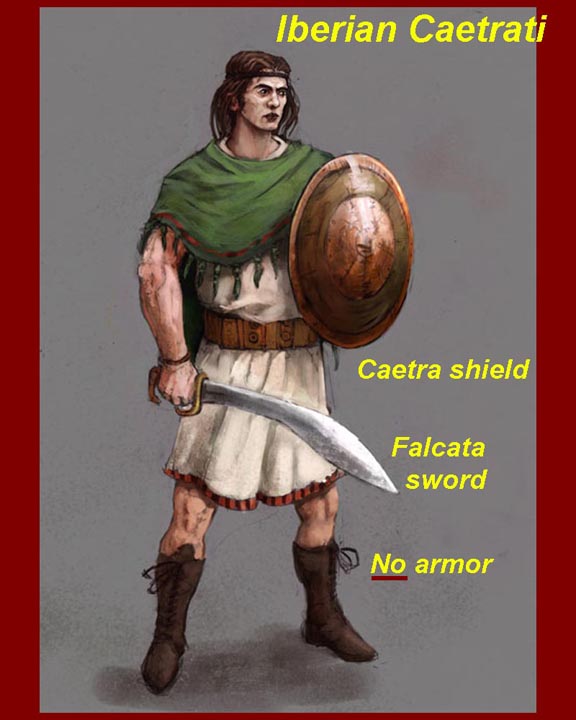

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0345IberianCaetrati3.jpg

Iberian Caetrati carried a Caetra shield and often used the slashing falcata sword.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0346IberianCaetrati1.jpg

Another of the Iberian Caetrati.

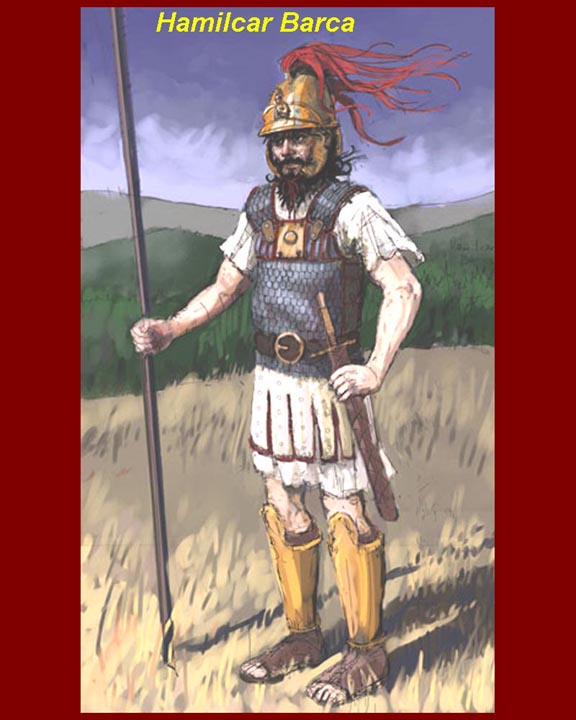

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0347HamilcarBarca.jpg

Hamilcar, the father of Hannibal, led the land forces of Carthage in Sicily -- by the end of the First Punic War it was a ragtag guerilla band. According to Polybius, it was Hamilcar who, in the period between the First and Second Punic Wars, trained Hannibal in Spain and inculcated Hannibal with a profound hatred of Rome.

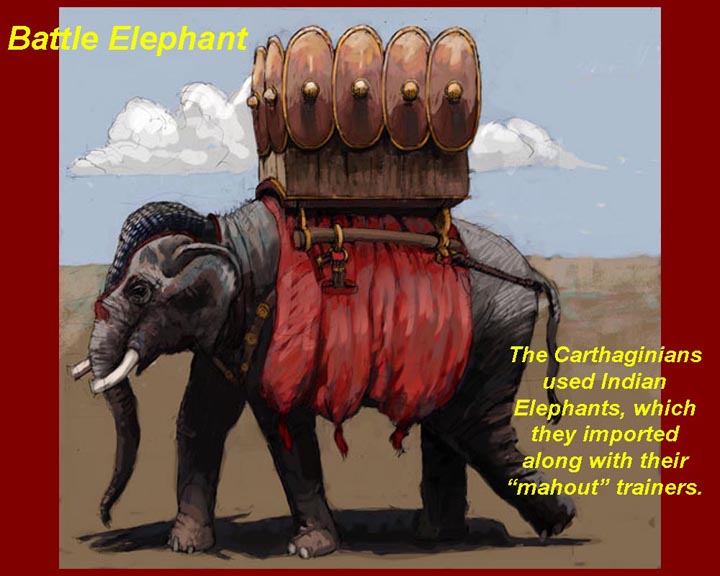

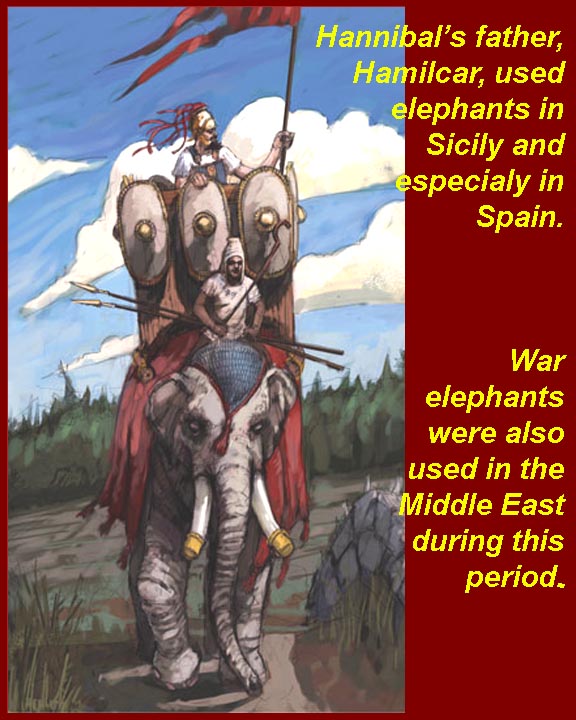

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0348Elephant2.jpg

A fanciful Carthaginian war elephant. Elephants were native to northern Africa during this period. They were smaller than the sub-Saharan breed, but still plenty scary when they ran at you. Carthage did not originate the use of elephants in Mediterranean warfare: they had been used for a long time in areas further east. Their trainers were imported from India. Hamilcar had elephants on Sicily. It's highly unlikely that the Carthaginians ever put howdahs on the back of thei elephants. The first use of elephants in battle in the western Mediterranean was apparently by Pyrros, who used them against both the Romans and the Carthaginians; they had, however, already been used in the eastern Mediterranean before their use by Pyrros.

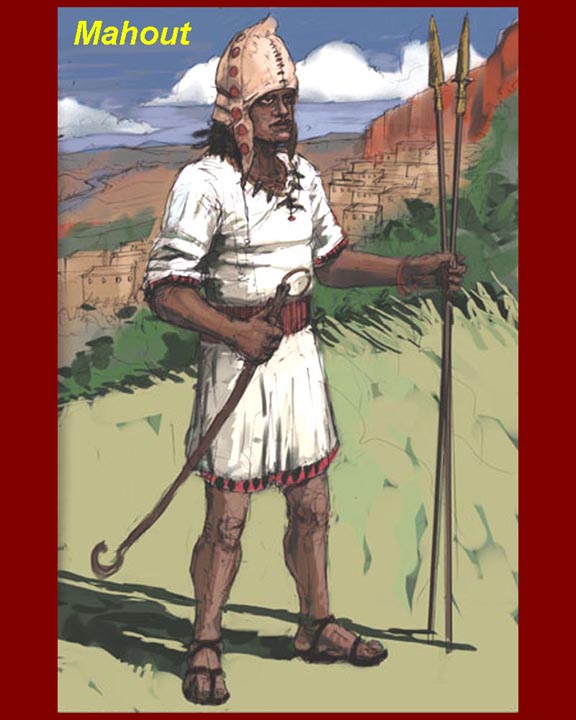

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0349ElephantMahout.jpg

An elephant trainer and driver -- probably an Indian -- carried his goad and spears.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0350aElephant.jpg

Hamilcar "on his elephant" in Sicily. The elephant's head covering was practical: prevented sunburn

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0350bPyrrhicElelephant.jpg

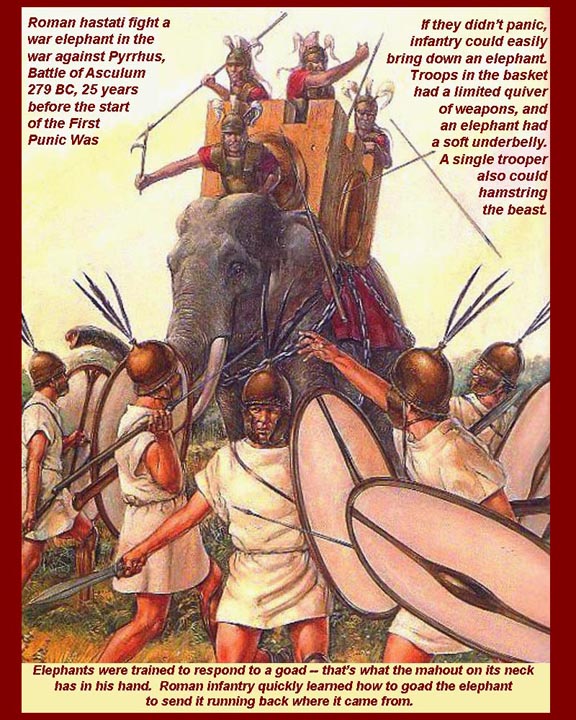

Roman infantry knew how to bring down an elephant, but the preferred defensive strategy was to goad them into turning around and running back where they came from. This image shows both the wrong kind of elephant, and the wrong kind of goad in the hand of the mahout, and, of course, another of those probably non-existent howdahs..

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0351CeltIberian1.jpg

Celtiberian light infantry carrying a scutum shield and a Celtic long sword. The Iberian short sword, which the Romans adopted and called a gladius, was shorter and therefore more useful for close quarters fighting.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAF0352CarthaginianHeavyInfantry1.jpg

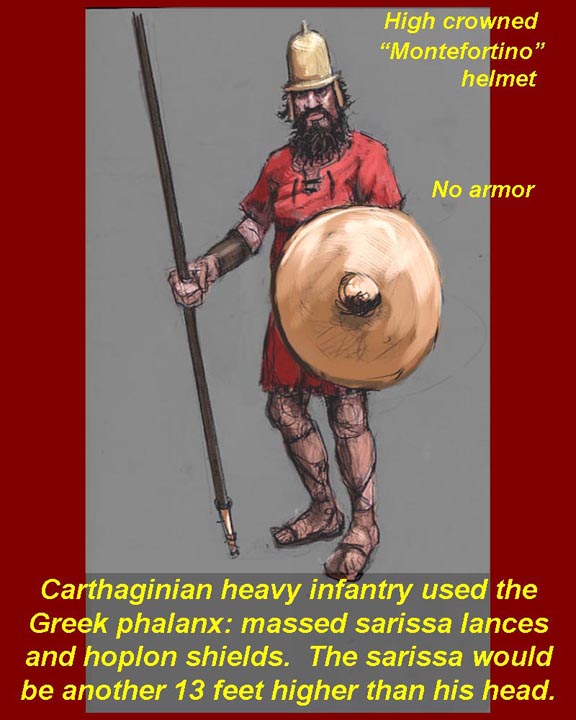

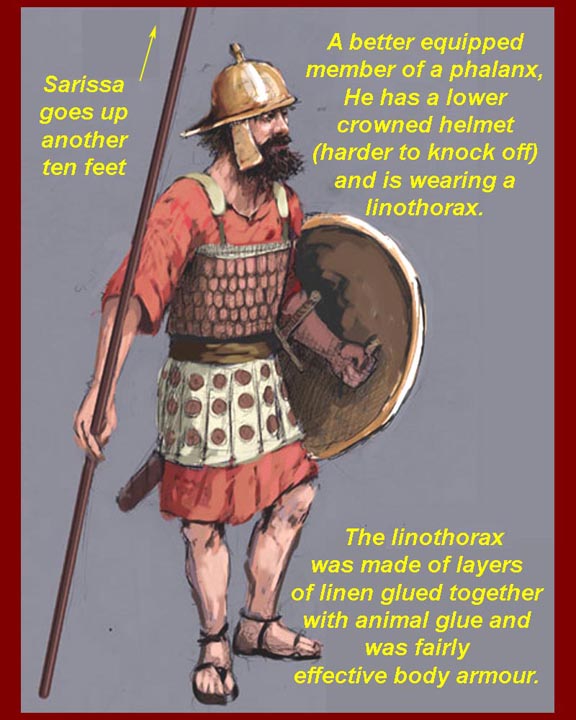

An individual member of a phalanx was something you would never see on a battlefield. They bunched together in groups of 256: 16 abreast and 16 deep. Each of these heavy infantrymen carried a shield and a 18 to 20 foot long lance called a sarissa.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAF0353CarthaginianHeavyInfantry2.jpg

This phalangist is wearing a linothorax -- body armor made of layers of linen glued together with animal glue.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0354CarthHoplite2.jpg

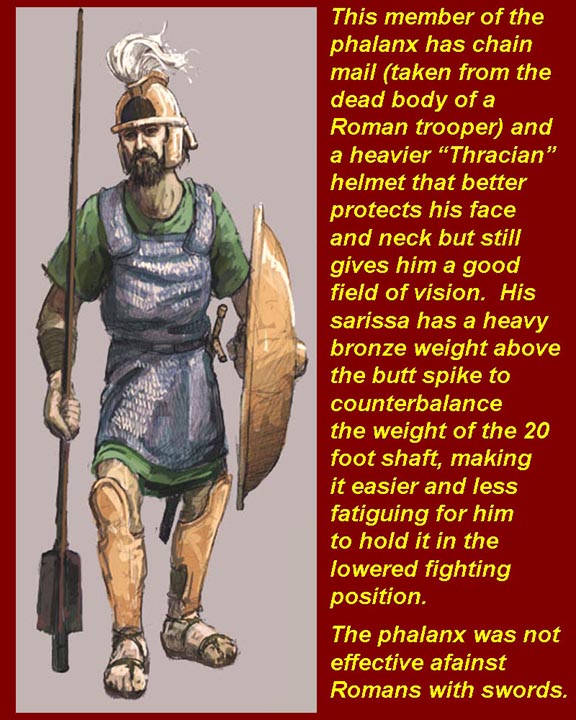

A phalange member wearing chain mail. Carthaginian soldiers soon learned to strip the mail from the bodies of slain Roman infantrymen. Mail was much more efficient at turning a blade than was the linothorax. Note also that his sarissa lance has a bronze counterweight above the butt spike. This allowed the member of the phalanx to carry his weapon with much less fatigue.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0355Phalanx.jpg

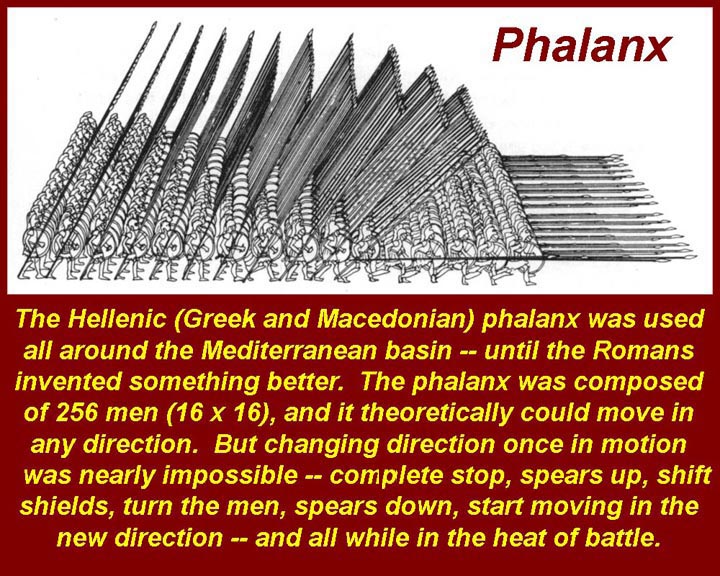

The standard infantry formation of Mediterranean armies of this period was this 256 man phalanx. It theoretically could move in any direction -- all the men would raise their spears, turn, and put their spears down again to move in a new direction. In practice, changing direction was extremely difficult, and protecting your flanks was virtually impossible.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0356PhalangesVPhalanges.jpg

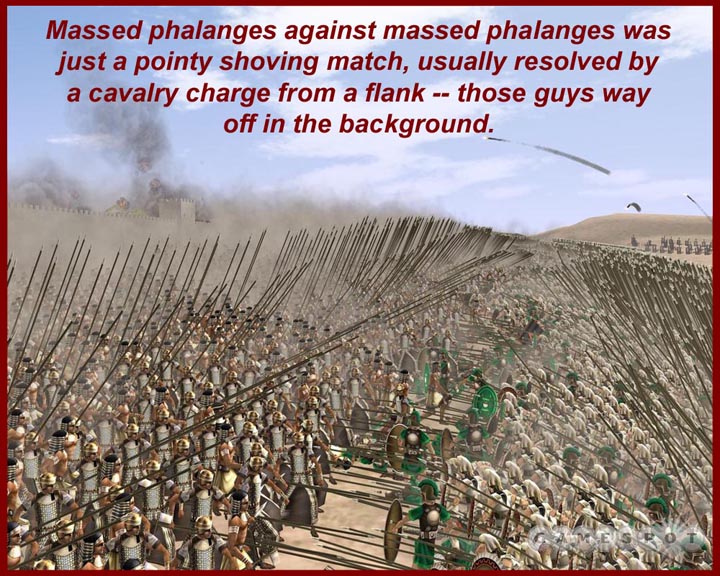

Commanders would pack their phalanges in side by side and flank them with protecting cavalry. Armies would face each other, and pointy shoving matches would ensue. Only the first five ranks would point their spears downward toward the enemies. This meant that between the front line of men in the phalanx five spears would protrude. The next image shows what you faced as a phalanx moved toward you.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0357PhalanxGaps.jpg

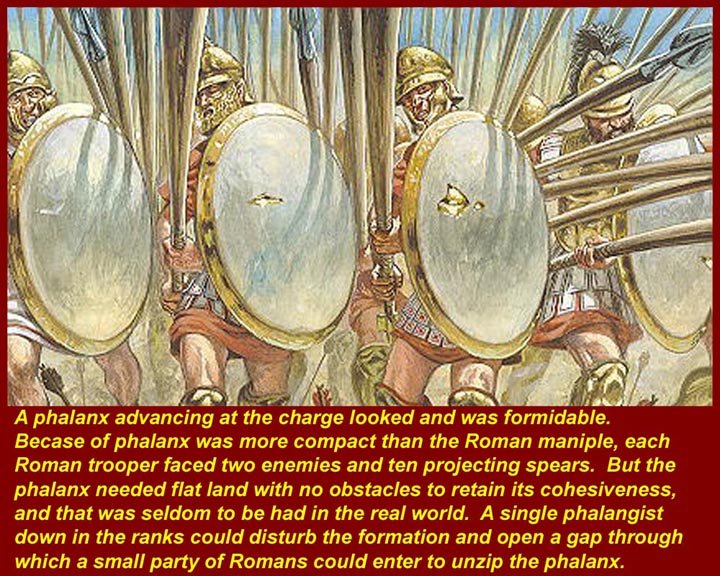

The Phalanx was packed tighter than the opposing Roman maniple. So individual Roman troopers (and they did fight as individuals) might face ten advancing sarissae. Pretty tough duty.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0358WhoWon.jpg

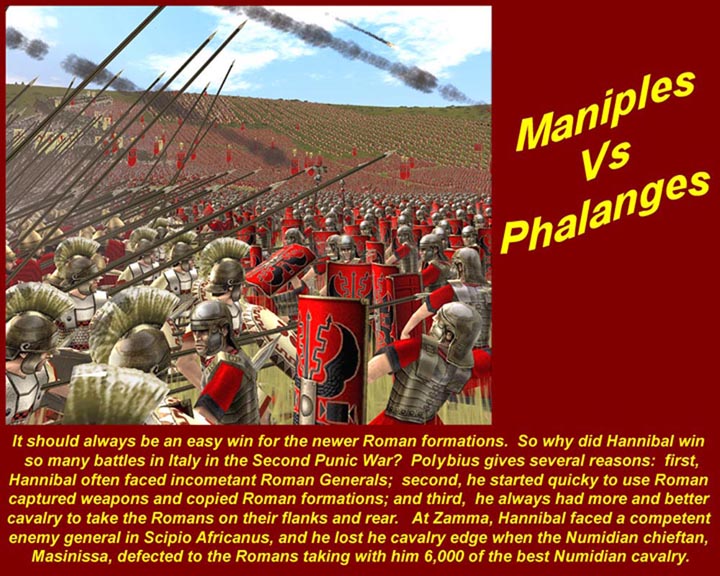

So why did the Romans win on Punic War battlefields? At the beginning, they didn't. Usually it was the Numidian cavalry that gave the victory to Carthage. But in Sicily and in Italy (Second Punic War) Roman maniples could beat the phalanx formations simply because they could maneuver and were able to adapt to uneven ground, obstacles, and even to dead men and horses on the field of battle. Any of those things could cause gaps in the phalanges that the Roman infantry could penetrate. Once inside, the Carthaginian sarissae were useless against the deadly Roman short swords (gladii, singular = gladius). That's what has happened in this image. (Carthaginans, by the way, were never that "uniform".) And once the Romans had learned how to panic and turn charging elephants, things got really bad for the Carthaginian phalanx formations. There was no way to get out of the phalanx unless everyone dropped their lances and fled at the same time.

(In the Second Punic War, Hannibal began to adopt the Roman formation and weapons, but by that time the Romans had again changed tactics and were completely avoiding set-piece battles in Italy. Instead, they left Hannibal to wander around in southern Italy using up his ever more scarce supplies and men in small skirmishes. Much more about that and about the big set-piece battle that the Romans finally did fight, at Zamma, will be in a later unit.)

The final score at the end of the First Punic War was Rome 1, Carthage 0. Rome had beaten the much vaunted Carthaginian fleet and the remaining Carthaginian coastal towns and ports, unable to be resupplied, had to surrender. Hamilcar was allowed to take his remaining land forces home. Unlike the Carthaginian admirals who had failed and had therefore been crucified by their own people, Hamilcar lived to fight another day. Carthage agreed to terms, which included paying Rome an indemnity.

Shortly after the First Punic War, Hamilcar was called back to arms to put down a revolt of unpaid mercenaries -- his own former troops. Then he went to Spain and started to plan the next war against Rome.