Maiuri was a long term and influential

Director of the

Excavations at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and surrounding areas -- served as

director from 1924 - 1961.

(Slide 1)

Pompeii and Herculaneum were

thoroughly buried by the eruption

of 79 AD. Pompeii appears to have

been abandoned except by scavengers -- either owners returning to try

to

recover items of special value, or looters on similar missions. A new town was eventually built over

the ruins of Herculaneum, but Pompeii was not resettled until it became

the

tourist attraction that it is today.

There had been warnings --

all in advance of the 79AD eruption:

"Scientific" analysis

of the igneous products

Legend and myth

1. Vitruvius

in De Architectura (date uncertain, but he died in

20 BC) had written: "Not

less also let it be recorded that heats in antiquity grew and abounded

under

Mount Vesuvius, and thence belched forth flame round the country" (Book II, Chapter 6, Para

2) Vitruvius described both the

characteristic "pozzulana" (i.e., Puteuli = Pozzuoli) sand, which he

found good for making hydraulic cements and the pumice found in the

area, both

of which he ascribed to volcanism.

2. Virgil,

in 19 BC, included in his Aeneid the long-standing

myth that the giant, Mimas, was buried under Vesuvius by the god

Hephaistos

(Vulcan) and the brother of Mimas, Enceledus, was buried under Etna in

Sicily. Earthquake were his

struggles to rise, rumblings his plaintive voice, and eruptions his

flaming

breath. Like today, Etna was

perennially active in ancient times, so there could be no mistaking the

meaning

of the ancient myth: Vesuvius was

also a Volcano.

3.

The Greek

historian Strabo, in 9 AD, that

Vesuvius "possesses craters of fire that go out only when they lack

fuel".

(Slide 2)

In addition, there had been

numerous earthquakes including big

quakes in 62 and 64 AD.

These two major quakes

virtually knocked down Herculaneum and

Pompeii.

Three things to

note:

Most damaged temples were

not

rebuilt by 79 AD, but the Isis temple was quickly rebuild and

sumptuously

decorated. (Similarly,

"Egyptian" mythological representations were widely represented in

private and public buildings.)

Isis was on the rise and Roman "pagan" religion was rapidly

waning, and that could have been one reason why the pagan Mimas myth

might have

been unknown or ignored.

The rebuilt

structures, including the Isis temple, were in mint

condition when they were entombed, giving us a snapshot of building

methods,

decoration, and lifestyles.

Maiuri -- the

long-term site director (1924 Ð1961) maintained that

the earthquakes upset the social order in the cities and that a new

middle-class displaced the Patrician elites, even to the extent of

taking over

many of their houses. Very

recently, Maiuri's "social" interpretation (and many others of his

conclusions) has been persuasively challenged. More

on this later.

What did the looters,

excavators, and archeologists have to dig

through?

Burial of the cities was

quick and deep.

(Slide 3)

2.4 meters of ash mixed with

small pumice clasts fell during the Plinian phase.

(Slide 4a)

Then a few inches of mixed

debris -- tiles, bricks, broken masonry, etc. from the first

pyroclastic surge. This was the layer in

which the victims

who were outside were found -- knocked down and killed instantly by the

extreme

high temperatures.

Then another 2.5 - 3 meters

of

ignimbrite deposited by one or more pyroclastic flows.

People who were inside were killed

rapidly (unconscious in a few seconds) by the extreme high

temperatures. The

flows arrived only a few seconds after the surges:

most volcanologists, as we have seen, talk about linked

surge/flow pairs -- you can't get one without the other because they

are, in

fact gravity-differentiated aspects of the same phenomenon..

Interestingly, it appears

that

the first surge/flow pair stopped against the walls of the city of

Pompeii --

not because the walls were especially strong but because the surge/flow

just

came that far.

Because the ash-fall had

already buried

things up to 2.4 meters deep, it was at that level that everything was

broken

off and destroyed by the surge that swept over the city.

That meant that buildings lost upper

stories if they had any. Walls

that were perpendicular to the direction of the surge were knocked

down, but

some few walls that happened to be parallel to the direction of the

surge

survived. The surge and flow acted

like a liquid (i.e., fluid mechanics determined where it went) so they

did eddy

around structures: it wasn't at all safe to hide behind something or

inside a

structure. And also, of course,

the ambient temperature could have instantly risen to as much as 1000

degrees

F. depending on how close you were to the origin of the surge/flow.

No later lava flows from

effusive

eruptions of Vesuvius reached as far as Pompeii, and only thin layers

of ash

reached that far.

The ash fallout

missed Herculaneum because the wind was blowing

the other way.

Contrary to what you might

have

heard elsewhere, Herculaneum was not just buried by Lahars (mud flows).

(Slide 4b)

There are at least five

surge/flow pairs everywhere at the Herculaneum site, and six pairs at

most

places. The first pair reached

almost to the old coastline and the next five overwhelmed the whole

city. Since only the area near the old

coastline has been excavated, it's possible that additional pairs might

exist

further inland.

It appears that part of the

population of Herculaneum made their way to the shoreline during the

Plinian

(ash-fall) period of the eruption (the first 10 -- 12 hours, which

almost

completely missed Herculaneum) in the hopes of escape by sea. They would have been at the water's

edge below the lip of a previously existing ignimbrite cliff. It's possible that some could have survived

the first surge/flow pair, which barely reached the shoreline. Shortly thereafter, the second much

bigger and more energetic pair would have overwhelmed everyone, even

those who

had sheltered in the boat storage areas cut into the cliffs -- fluid

mechanics

(and the Coanda effect?) would have ensured that the storage areas

would have

filled with pyroclastic material.

The shoreline at Herculaneum

was

extended outward by more than half a kilometer by the accumulated

volcanic

matter from the 79AD eruption. At the old shoreline (where most of the

actual

excavation, as opposed to tunneling has taken place) there is an

overlay of 20

meters.

Herculaneum was originally

built

on a layer of ignimbrite from a previous eruption -- probably from the

Campi Flegrei

rather than from Vesuvius. The

site of the city actually ramped upward slightly toward the seacoast. That upward ramping, along with the 20

meters of 79 AD deposits, makes the site higher than surrounding areas,

so

lavas from later effusive eruptions of Vesuvius have flowed around the

site. Minor ash falls from later

Vesuvius eruptions overlay the 79 AD ignimbrite layers.

Why dig at all? And

why is Pompeii so popular?

[Coincidentally, it's now

possible

to make a good living as an archeologist.]

In

the 1800s there was a huge

interest in Pompeii -- and it began just as modern archeology and, more

importantly, modern tourism was being born. The

continued appeal of the subject is clear from the many

movies and TV shows made about Pompeii and Vesuvius.

(This is an isolated phenomenon, not just because of

disaster and casualties: there

have been other bigger catastrophes that have been forgotten

(Slide 5)

Last Days of

Pompeii -- Edward

Bulwer Lytton's

1834 good luck: August Eruption and

September Publication

(Slide

6)

Pompeii

in popular art

(Slide 7)

Mark Twain's Innocents

Abroad

and

Clemens on the lecture circuit

(Slide 8)

The Vesuvius Funicular and its song

Excavation History

Everyone knew what had

happened

-- the sound was loud enough to be heard in Rome, and the

Plinian

column was visible from Rome.

(Slide 9)

The Historian Tacitus wrote

about

the eruption -- but his description is lost to us.

We know he researched the subject because of Pliny's

letters, which have been preserved.

He may have had other eyewitness accounts.

(Slide 10)

There were people digging

around

in the rubble in ancient times

(Slide 11)

"Looters" holes are not

uncommon, although we are not really sure whether they were made by

looters, or

rescuers, or owners trying to recover their buried property. It also has been

suggested that some might have been made by people

trying to escape, but that explanation doesn't take into account the

speed of

death that accompanies superheated flows.

But in the "Dark Ages"

the sites were genuinely forgotten

Renaissance digging:

Domenico Fontana (end of the

1500s)

The Fontanas

were the favorite

architects of Pope Sixtus V (Felix Peretti, Pope from 1585-90).

(Slide 12)

Major projects in Rome --

erecting the Egyptian Obelisks, including the one in front of St.

Peters

undertaken by Domenico.

His brother Giovanni made

the

Aqua Felice ("Felix's aqueduct") work after other architects had

botched the job by mis-figuring the slopes of the water channels.

(Slide 13)

Domenico was hired by Count

Muzziu Tutavilla to bring clean water down from the hills to family

lands and

towns on the Bay of Naples.

Tunnels for the Sarno/Foce aqueduct passed right through the

Pompeii

site (right over the top of the amphitheater) and through the ruins of

the

city. Apparently nothing of value

was seen, so no digging was undertaken. Locals called the site "La

Civita" or "La Citte" but did not know it was Pompeii -- it was

known that there were ancient Roman ruins -- mostly villas -- scattered

about.

(Slide 14)

The top, i.e., the outside

of the

stones that were put in to support the top of the tunnel, can still be

seen in

Pompeii, where the volcanic debris was later removed.

Well digging, 1689

Inscriptions were tuned up,

one

of which mentioned "decurios Pompeiis". A

noted Neapolitan architect, Francesco Piccheti,

mis-identified the site as the villa of Pompey the Great, Julius

Caesar's

opponent in the Civil War of 51 -- 47 BC.

Another scholar, Francesco

Bianchini, correctly identified the site as Pompeii, and four years

later,

Giuseppe Macrini did some exploratory digging and found the outer walls

of the

city -- clearly city walls of a type that would not have been around a

villa.

Nonetheless, Piccheti's

views won

out, and academia did not believe the Pompeii identifications.

More well digging, 1709

Workers dig right into the

seats

of the Herculaneum amphitheater.

The local Prince, Emmanuel-Maurice duc d'Elbeuf, got wind of the discovery and within a few years was mining the site to build and decorate his Villa on the Bay of Naples, first for marble (amphitheater seats) and the for statuary and frescoes -- beginning of a long tradition of looting by the nobility. Most of this was concentrated at Herculaneum.

(Slide 15)

Pompeii, 1748, Roque Joachim de Alcubierre, a Spanish military engineer working for Charles III (VII) Bourbon y Farnese, King of Naples.

The Herculaneum "mine" was playing out, so Alcubierre looked elsewhere -- investigated local lore and came up with the idea of digging in "La Citte".

Alcubierre's work was heavy handed and destructive, and, of course, not documented (Although the ancient Romans had dug and documented (and collected and looted) the documentation tradition had been lost.) Alcubierre only recorded important finds (that were literally "noteworthy" -- and threw almost everything else back into the pits, which he promptly backfilled with debris from his next excavation.

Digging in the loose overlay of Pompeii was much easier but also was much more dangerous than in the consolidated overlay at Herculaneum -- landslides, cave-ins, and poison gas pockets ("mofeta") took their toll.

Pompeii, 1750, Karl Weber, a Swiss military engineer, arrives -- "co-Director" with Alcubierre for Charles III.

(Slide 16)

Weber attempted to rationalize and document, but the artistic and architectural (and precious metals and stones) "treasure" was what Charles really wanted to collect, so Alcubierre could often over-ride Weber whose efforts seemed to be slowing down the discovery of valuables.

Weber, nonetheless, sometimes had his way and even dragged the King out to the digs on occasion.

At any rate, Weber's maps, plans, and documentation survive.

(Slide 15 again)

Charles was, of course, a very successful collector of Pompeian and Herculaneum art and artifacts. His collection was the basis for the National Archeological Museum in Naples.

(That museum, continues to be the main repository for what comes out of the Pompeii and Herculaneum digs. The Capodimonte Royal Palace houses the Renaissance collection s, which are also splendid.)

Weber died in 1764 after working with Alcubierre for fifteen years

Francesco La Vega, 1764

La Vega was Weber's worthy replacement -- worthy because he was the first ot understand the tourism value of Pompeii.

(Slide 17)

Excavated areas were preserved and documented, guides were published, and the great art of Pompeii and Herculaneum was illustrated into scholarly volumes. It's clear that there was even advertising, and distinguished visitors -- popes, princes, scholars -- started to show up.

(Slide 18)

An early triumph of La Vega (1764) was the discovery and excavation of the Temple of Isis -- it had been one of the few Pompeian temples reconstructed after the 62/64 earthquakes and it was in a very good state of preservation. It had been brand new when buried.

(Slide 19)

The decoration of the Isis temple and the clothing shown in the temple frescoes (and in other Egyptian/Isis influenced decoration in Pompeii) had a great influence in Europe. When Napoleon came to power in France (he was born in 1769 and reached the height of his power around 1800) Napoleon, who fancied himself as the new Roman Emperor, emulated the (Egyptianised) decor of Pompeii and the women of his court wore the "Empire" style copied from the Isis temple frescoes.

Napoleonic Period at Pompeii

Napoleon's forces took Naples in 1798 and Joseph Bonaparte became King of Naples. He was interested in the archeological sites and hires Michele Arditi to create and excavation plan -- essentially to uncover the city walls and work inward toward the center. This plan stayed pretty much in effect until recently when the current director decreed that there would be no new digging (except downward) until already-exposed material was consolidated -- more on that later.

Joseph was eventually pulled out to take over the Monarchy in Spain, and the Kingdom of Naples was given to Marshal Joachim Murat (Marshal 1804, King of Naples 1808-15). Murat married Caroline, a Farnese heiress. (The mother of Charles III had also been a Farnese -- Elizabeth -- so Caroline brought some continuity to the Neapolitan throne). More importantly, Caroline brought old and real money to the Kingdom's treasury, and she had some influence on how it was spent.

(Slide 20)

She financed extensive digs at Pompeii and was the patroness of the Charles Francis Mazois Les Ruines de Pompeii, a three volume set book on everything that was then known about the city.

Caroline also brought many of the Farnese treasures -- art and statuary of ancient Rome from the Farnese family collections -- to Naples where they still remain in the National Archeological Museum. Her marriage to Murat did lead to some legal complications concerning the return of art works that were transferred from Naples to Paris during Napoleonic period.

The Congress of Vienna ended

Murat's reign and the "good old days" of Carolinian Patronage.

The digging continued

unabated,

but not at the rate she had sponsored.

(Slide 21)

Alexandre Dumas, Garibaldi,

1860

In 1860 Garibaldi conquered the Kingdom of Naples and almost immediately turned it over to the united Kingdom of Italy. Garibaldi was left in charge of the Neapolitan province, and he appointed Alexandre Dumas, the author, as Director of Excavations.

Dumas had, by that time produced over 250 books and 15 plays, but he had no experience with archeology (Yes, 250!, but Isaac Azimov produced over 500 books in the 20th century.) Dumas acknowledged 73 "assistants", who helped him write.

Dumas's major accomplishment was to organize and publicly display the collection of Pompeian erotic art in the National Museum. The erotica had been locked away "the Secret Cabinet" in Royal times (1819) to protect the morals of the Neapolitans. The "Cabinet" was locked up again later in more prudish times by Mussolini's fascists. The Secret Cabinet was ostensibly only opened for scholars, but for a few thousand Lira (a couple of dollars) almost anyone could get in. It was finally officially open to everyone again in 2000, a move that was condemned by the Church. (All of this stuff is now available, of course, on the Internet. A representative sample is at http://www.answers.com/topic/erotic-art-in-pompeii.)

August Mau 1860 –

'85

Giuseppe Fiorelli, 1863

Fiorelli was appointed in 1863 (under Dumas) to head the dig at Pompeii. He already had wide experience at Pompeii and elsewhere.

Fiorelli introduced modern archeological principles: stratigraphy, in particular, enabled him to deduce the presence and uses of upper stories, which had collapsed.

Fiorelli developed the locator system of naming locations by "regions, blocks, and doorways", the system still in use today.

(Slide 22)

Less importantly, but much more famously, he developed the "Fiorelli method" of flowing plaster of Paris into cavities where objects and people had decomposed. This method produced the famous "plaster people", but it has also enabled archeologists to record such things as food, furniture, and plant material. [My project was casting grape-vine root structures at a suburban villa. -- tkw]

Fiorelli was promoted and transferred to national archeological responsibilities in Rome in 1875, but he had established a working regime that has lasted in most respects until the present time.

Vittorio Spinazzola, 1910

Spinazzola's major accomplishment was the initiation of restoration and preservation projects carried out simultaneously with new digs.

He has been criticized for digging out only the front facades of buildings along major streets without supporting them. This procedure did, however yield a good deal of new knowledge about ancient building methods, town planning, and, in particular, the uses to which second stories were put.

He was removed in 1924, apparently because he would not kowtow to Mussolini's nationalist and ideological interpretations of the Roman Empire -- he thought and said that Mussolini was a fool.

(Slide 23)

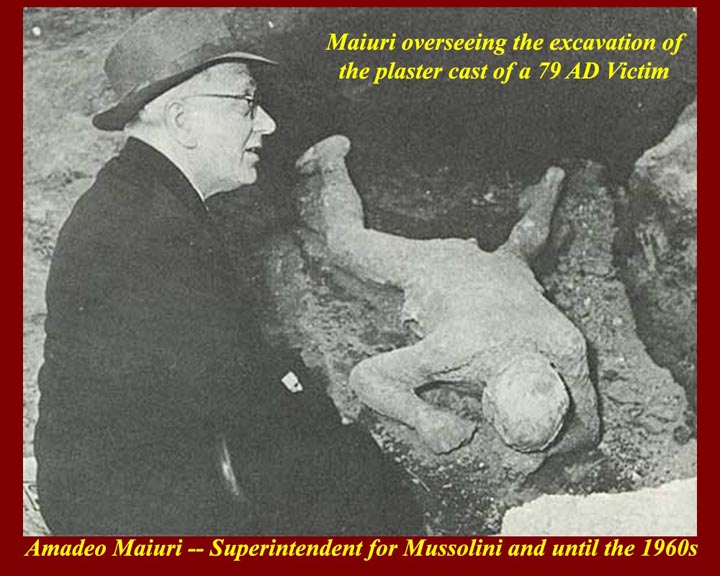

Amedeo Maiuri 1924-1961.

You either love him or hate him. Maiuri started with two strikes against him: he had replaced an efficient and popular director, and he was considered to be Mussolini's man. In fact, only the first was of any consequence at the time that he took over the job: it was very popular, at the time, to be Mussolini's man. We will never know whether Maiuri really was a fascist ideologue, as his detractors say, or whether, like so many others, he simply did what was needed to get his job done.

In terms of sheer mass, Maiuri certainly moved more dirt than any other Pompeian excavator.

From the beginning, his methods were modern and scientific, especially in stratigraphy, context, and record keeping.

He was often (even after Mussolini) under great pressure to produce impressive finds, and his critics claim that this became habitual -- that he wanted great finds even when the pressure eased off.

Maiuri had what some critics called a Fascist economic agenda, which amounted to demonstrating that the old Roman patrician faction of Pompeii had been displaced by a new mercantile class by the time of the 79 AD. The reason for this change was the destructive series of earthquakes in 62 - 64 AD from which, Maiuri maintained, the upper class never recovered. The symptoms of the change were many, but two were most easily detected.

First was a supposed change in decorative art styles in homes and public buildings, the advent of the "fourth style" -- actually a conglomeration of the "second" and "third" styles (much more about the four "styles" in a separate unit). Maiuri considered the fourth style degenerate and said that its advent indicated that a degenerate class had taken over.

Second was the supposed conversion of living space to commercial space in Pompeian houses after the earthquakes. (We'll also go into this question more in a later unit.)

Other criticisms of Maiuri include:

His high estimate of Pompeii's population at the time of the eruption: that 20,000 figure that is often used was his. Many recent scholars have gone toward the lower end, around 6000.

His overestimation of the number of houses that had upper floors and the assumptions about uses for those rooms: he thought many were rented apartments.

The connection between the number of doors an stairways in large houses with the number of families living in the house.

His views on the use of living space by the ancient Pompeian familia or extended family, which would include relatives, slaves, freedmen, employees, candidates for adoption, and possibly others. The presence of transient or permanent guests as well as the daily obeisance of clients was also a factor.

Maiuri also stands accused of selective publication and even selective preservation of artifacts and structures. This criticism, however, is more a function of changing priorities (and to some extent "political correctness") than of "bad archeology" by Maiuri. The latest fad in archeology is to discover and publish what all classes and levels of ancient society were up to, and that's very different from what was considered important in earlier days.

[I tend to sympathize with Maiuri on this last point: it's nice to know (actually conjecture) what the lower classes did and how they lived, but, because they were "unimportant" in their own time, evidence about them is harder to find and, therefore, accurate deductions about them are harder to make. Also, the lower classes, especially in ancient times, seldom had much effect on "history", i.e., on the events and circumstances that had effects and set parameters for later days, including our own. For example, our own founding fathers, in setting up the American Republic, worked from the upper class pattern of power sharing of republican Rome (before the tumult of republican Rome's last century). They might not have had an accurate perspective on Roman life, and they certainly were not "politically correct", but the historical fact remains that they worked from the upper class pattern.

It's also important to remember that the source of most criticism of earlier scholarship , including Maiuri's, comes from non-representative leftist academia, and to remember the old adage, "Those who can't do, teach."

This shows signs of becoming a rant, so I'll stop -- but you get the point.]

A final note on Maiuri: It has been asked whether Maiuri reached an accommodation with the Camorra, the Neapolitan criminal organization, which is akin to but more institutionalized than the Mafia. The answer, of course, is another question: "Are you talking about Naples?"

After Maiuri

"Quick succession" (by the standards of the long-running Maiuri) of Directors, although the titles fluctuate:

Alfonso de Franciscis, 1961 - 76. Superintendent of Archeology for the Provinces of Naples and Caserta

Fausto Zevi, 1977 -- 81. Superintendent of É etc. A major earthquake shakes the region doing great damage to Pompeii and Herculaneum. Both sites were closed for safety surveys, and Pompeii requires extensive structural repairs before reopening. Some areas are still closed to the public today.

Giuseppina Cerulli Irelli, 1981 -- 84. Superintendent for Pompeii

Baldassare Conticello, 1984 -- 95. Superintendent for Pompeii

(Slide 24)

Pietro Giovanni Guzzo, since 1995 (unless the changed since this was written). Superintendent for Pompeii

There was, of course, ex post facto sniping after each change took place.

In the modern Italian fashion, Conticello was actually indicted for his "crimes" of favoritism and not following procedures.

(Slide 25)

Vicissitudes:

The big problem is always money. There is never enough, and there is always what is quaintly known as wastage -- some of it disappears.

Natural disasters -- another eruption in 1944 and a big earthquake on Nov 23, 1980.

Man-made disasters

Both Pompeii and Herculaneum were bombed in the two 20th century World Wars.

Looting and vandalism continues.

It's still Naples, so there's still corruption.

Controversies:

All major expansion of the exposed area (two-thirds to three-fourths of the city, depending on who's counting) has been stopped while conservation, preservation, documentation, cataloguing, etc. is supposed to catch up.

Herculaneum's Villa dei Papiri -- should there be more digging?

The state of the Volcano -- when will it pop again, and how devastating will it be? How should that effect the pace of excavations?